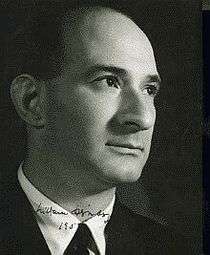

William Steinberg

William Steinberg (Cologne, August 1, 1899 – New York City, May 16, 1978) was a German-American conductor.

Biography

Steinberg was born Hans Wilhelm Steinberg in Cologne, Germany. He displayed early talent as a violinist, pianist, and composer, conducting his own choral/ orchestral composition (based on texts from Ovid's Metamorphoses) at age 13. In 1914, he began studies at the Cologne Conservatory, where his piano teacher was the Clara Schumann pupil Lazzaro Uzielli and his conducting mentor was Hermann Abendroth. He graduated with distinction, winning the Wüllner Prize for conducting, in 1919. He immediately became a second violinist in the Cologne Opera orchestra, but was dismissed from the position by Otto Klemperer for using his own bowings. He was soon hired by Klemperer as an assistant, and in 1922 conducted Fromental Halévy's La Juive as a substitute. When Klemperer left in 1924, Steinberg served as Principal Conductor. He left a year later, in 1925, for Prague, where he was conductor of the German Theater. He next took the position of music director of the Frankfurt Opera. In 1930, in Frankfurt, he conducted the world premiere of Arnold Schoenberg's Von heute auf morgen.

He was relieved of his post in 1933 by the Third Reich because he was Jewish. According to the grandson of composer Ernst Toch, Steinberg was "rehearsing [Toch's opera Der Fächer (The Fan)] in Cologne when Nazi brownshirts came storming into the hall and literally lifted the baton out of his hand".;[1] Steinberg, who had married Lotte Stern in Frankfurt in 1934, was then restricted to conducting concerts for the Jewish Culture League in Frankfurt and Berlin. The Steinbergs left Germany in 1936 for the British Mandate of Palestine, which is now Israel.[2] Eventually, with co-founder Bronisław Huberman, Steinberg trained the Palestine Symphony Orchestra, which would later be known as the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. Steinberg was conducting the orchestra when Arturo Toscanini visited there in 1936. Toscanini was impressed with Steinberg's preliminary groundwork for his concerts and later engaged him as an assistant in preparing for the NBC Symphony Orchestra radio broadcasts.[3]

Steinberg emigrated to the United States in 1938. He conducted a number of concerts with the NBC Symphony Orchestra from 1938 to 1940. Steinberg conducted summer concerts at Lewisohn Stadium in New York (1940–41), led New York Philharmonic concerts in 1943-44, and also conducted at the San Francisco Opera. He became a US citizen in 1944, and was engaged as music director of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra from 1945 to 1952. He is best known for his tenure as music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra from 1952 to 1976. Steinberg's Pittsburgh appearances in January 1952 were so impressive that he was quickly both engaged as music director and signed to a contract with Capitol Records. Thereafter Pittsburgh was the center of his activity although he held other important positions. From 1958 to 1960 he also conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra, but eventually resigned that post because the added workload led to problems with his arm.[4] He led the New York Philharmonic for twelve weeks while on sabbatical leave from Pittsburgh in 1964-65, which led to his engagement as the Philharmonic's principal guest conductor from 1966 to 1968. From 1969 to 1972 Steinberg was music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (with which he had achieved earlier success as guest conductor) while maintaining his Pittsburgh post. He toured Europe with the Boston Symphony in April 1971.

These additional engagements often led to rumors that Steinberg would leave Pittsburgh for a full-time position elsewhere. In 1968 though he declared, "We are too closely wed, the Pittsburgh Symphony and I, to contemplate any divorce."[5] On another occasion Steinberg said that conducting had become the profession of a traveling salesman. "A conductor has to stay put to educate an orchestra."[6]

Steinberg guest-conducted most of the major US orchestras, including the Chicago Symphony, Cincinnati Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Dallas Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Seattle Symphony, and Philadelphia Orchestra. Abroad he conducted the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Berlin Philharmonic, Frankfurt Opera and Museum Orchestra, Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Montreal Symphony Orchestra, Munich Philharmonic, Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire, Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, RAI Orchestra of Rome, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra (in their 1955 Beethoven cycle), Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, Tonhalle Orchester Zürich, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, and WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne. He also appeared at summer festivals in the US and Canada (Ambler Temple University Festival, Hollywood Bowl, Ojai, Ravinia, Robin Hood Dell, Saratoga, Tanglewood, and Vancouver) as well as in Europe (Salzburg, Lucerne, Montreux). He conducted the Metropolitan Opera in several productions including Barber's Vanessa, Verdi's Aida, and Wagner's Die Walküre during his sabbatical in 1964-65.

Steinberg recorded Don Juan and his own suite from Der Rosenkavalier (works by Richard Strauss) with Walter Legge's Philharmonia Orchestra in the summer of 1957. The following year he conducted them in concerts at Lucerne before assuming the conductorship of the London Philharmonic. Steinberg's first recording was however made in 1928, when he accompanied Bronisław Huberman in Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto with the Staatskapelle Berlin. In 1940 Steinberg recorded excerpts from Wagner's "Lohengrin," "Tristan und Isolde," and Tannhäuser, as well as Mozart's "The Marriage of Figaro," with Metropolitan Opera members, issued anonymously on "World's Greatest Opera" records.[7] After the war Steinberg made a single album for the Musicraft label with the Buffalo Philharmonic - the premiere recording of Shostakovich's Symphony No. 7 in 1946. He led several accompaniments for concerto recordings on RCA Victor by Alexander Brailowsky, Jascha Heifetz, William Kapell, and Arthur Rubinstein.

Steinberg made numerous recordings for Capitol Records, all but two of them with the Pittsburgh Symphony. The exceptions included a recording with the Los Angeles Woodwinds of Mozart's Gran Partita, K.361, taped in Hollywood in August 1952, and the aforementioned Strauss disc with the Philharmonia Orchestra. His Pittsburgh recordings for Capitol, all made in the Syria Mosque, included concertos with Nathan Milstein and Rudolf Firkušný, as well as a cross-section of the symphonic repertoire from Beethoven to Wagner. Nearly all of Steinberg's Capitol recordings were reissued in a 20-CD box set by EMI in September 2011.[8]

In February 1960 Steinberg and the Pittsburgh Symphony moved to Everest Records, but by mutual agreement this contract was terminated after three releases since Everest abandoned their classical recording program. A casualty of this decision was a planned recording of Mahler's Sixth Symphony with the London Philharmonic, which was to have been made in conjunction with Steinberg's performance given as part of the Mahler centenary in London. Steinberg and the Pittsburgh Symphony in March 1961 signed a pact with Enoch Light's Command label. Light had attended a Steinberg concert in Danbury, Connecticut a few years before and told the conductor he'd like to record the orchestra. After the Everest contract lapsed, Steinberg subsequently made a number of technically acclaimed records for Command on 35mm film recording stock. The Command releases, hailed as "outstanding examples of contemporary recording," were made in the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Hall in Pittsburgh. Light preferred the sound of this high-ceilinged auditorium with its open stage to that of Syria Mosque for recording.[9][10] The initial Command recordings, Brahms Symphony No. 2 and Rachmaninoff Symphony No. 2, were taped on May 1–2, 1961. Steinberg's recording of the Brahms Symphony No. 2 was nominated for a Grammy for Classical Album of the Year in 1962.[11] Steinberg said of these sessions, "At first I opposed this location, because I can't hear the orchestra there, the ceiling is so high. I suppose it must be so high to make room for the Lincoln inscription. But the engineers said, 'The microphones hear very well, and we will use a lot of them.' Who am I to argue with the engineers? So we recorded in Memorial Hall. I am the only conductor in history who memorized the Gettysburg Address while rehearsing Brahms' Second Symphony."[12]

Steinberg's Command recordings eventually included complete cycles of the Beethoven and Brahms Symphonies, along with a diverse list of other works. Command's Pittsburgh Symphony activity ended after Steinberg recorded Bruckner's Seventh Symphony, his early Overture in G minor, two arrangements by Robert Russell Bennett, and Dimitri Shostakovich's Symphony No. 1 in April 1968.[13] When Steinberg assumed his post with the Boston Symphony in 1969, he made several recordings first for RCA, then Deutsche Grammophon, which contracted the Boston Symphony upon expiration of the RCA pact. His Boston recordings for both RCA and DG were of the first rank both musically and technically.

Steinberg received numerous awards, including both the Kilenyi Bruckner Medal and the Kilenyi Mahler Medal from The Bruckner Society of America.[14][15] He was named a member of the International Institute of Arts and Letters in 1960.[16] Steinberg was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame the same year. The Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce named Steinberg Man of the Year for 1964 for his contributions to the city's cultural life, and for leading the Pittsburgh Symphony on a triumphant tour of Europe and the Middle East.[17] He was also an honorary member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, the national fraternity for men in music.[18] Steinberg received an honorary doctorate of music from Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1954,[19] an honorary doctorate of music from Duquesne University in 1964,[20] and an honorary doctorate of humanities from the University of Pittsburgh in 1966.[21] He was named Sanford Professor of Music at Yale University in 1974. Steinberg died in New York City on May 16, 1978, having entered the hospital after conducting a New York Philharmonic concert on May 1 that featured violinist Isaac Stern.[5]

William Steinberg was noted throughout his career for his straightforward yet expressive musical style, leading familiar works with integrity and authority such that they sounded fresh and vital. Despite the dynamic drive of his interpretations, his podium manner was a model of restraint. Steinberg said of his interpretive philosophy, "One must always respect the character of the music and never try to grow lush foliage in a well tempered English garden."[22] Referring to some of his more acrobatic colleagues, Steinberg remarked, "The more they move around, the quieter I get."[23] Pittsburgh principal flute Bernard Goldberg told how Steinberg "looked forward to being 70 years old because only then did a conductor know what he was doing."[24] Armando Ghitalla, distinguished Boston Symphony principal trumpet from 1966–79, said of Steinberg that "his musical taste was one of the finest I've ever heard."[25] Boston Symphony concertmaster Joseph Silverstein said Steinberg was "as sophisticated a musician as I have ever known."[26]

Steinberg had a wide range of repertoire, including a sympathy for the English music of Elgar and Vaughan Williams. He led several important premieres, including the US premiere of Anton Webern's Six Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 6. During his first Pittsburgh season, Steinberg conducted works by Bartók, Berg, Bloch, Britten, Copland, Harris, Honegger, Milhaud, Schuman, Stravinsky, Vaughan Williams, and Villa-Lobos at the Pittsburgh International Contemporary Music Festival (all of these performances appeared on record, and the Bloch, Schuman, and Vaughan Williams were licensed by Capitol). He was also admired as an interpreter of Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, Mahler, Strauss, and Wagner. He made a famous recording of Holst's The Planets with the Boston Symphony for Deutsche Grammophon, after learning the piece at the age of 70. Unusual for a conductor born in Europe, Steinberg was a sympathetic conductor of George Gershwin's music (he made Gershwin recordings for three different labels). His last Metropolitan Opera appearances were three performances of Wagner's Parsifal in April 1974.

Although sometimes criticized for his unusual programming, Steinberg was a champion of certain lesser known works including Berlioz's Roméo et Juliette, Tchaikovsky's Manfred Symphony, Reger's Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Mozart, and his own orchestral transcription of Verdi's String Quartet in E minor. Steinberg said, "The literature is so enormous. I look into what my colleagues won't. Actually, I am not success minded. I merely dare. I take a risk. Criticism I get anyway."[27] Steinberg's prestige however filled Carnegie Hall to 80 percent capacity under the unlikely circumstance of the first all-Schoenberg orchestral program ever given in New York.[28]

Steinberg once remarked to a San Francisco Symphony musician he corrected, "I may be wrong, but I don't think so." Violinist David Schneider said, "This quality of not taking himself too seriously endeared him to the musicians."[29] Although all business on the podium, Steinberg was not above a bit of clowning in public; at one Pittsburgh Symphony fundraiser, he donned a blonde wig on his bald head that Johnny Carson jokingly presented him. Steinberg's puckish humor was often in evidence, as when he told Time Magazine that he had conceived "something for the New York snobs—an all-Mendelssohn program. This is really the height of snobbishness, the wonderful answer to the question of just what do the snobs need."[30] He said that he spoke four and a half languages - the half being English.[5] Of his habit of eating a steak before every concert he conducted, Steinberg told a columnist, "So you see, it's an expensive business - this concert conducting."[31] Referring to a disagreement with violinist Nathan Milstein that led to Milstein walking out of a rehearsal, Steinberg said, "He decided he would not stay and I decided I would not have him."[32] Concerning acoustics he said, "If the hall is resonant, the tempos must be changed. If the acoustics are too bad, you go fast in order to go home quickly!"[33] To an interviewer who said he had heard that the conductor did not care for giving interviews, Steinberg replied that it was fine as long as the subject was one that interested him - "for instance, myself."[34]

Conductor and music director

- 1924 Oper Köln

- 1925–1929 Prague State Opera

- 1929–1933 Oper Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main

- 1936–1938 Palestine Symphony

- 1945–1952 Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra

- 1952–1976 Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

- 1958–1960 London Philharmonic

- 1969–1972 Boston Symphony Orchestra

Selected discography

Recordings made with the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra for Musicraft:

- December 4, 1946 Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 7, "Leningrad" (This was the first commercial recording of the work)

Recordings made with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra for Everest Records:

- February 13, 14, 16, 1960 Robert Russell Bennett: A Commemoration Symphony (based on works by Stephen Foster); A Symphonic Story of Jerome Kern

- February 13, 14, 16, 1960 Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 4

- February 13, 14, 16, 1960 George Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue (with Jesus Maria Sanroma), An American in Paris

Recordings made with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra for Command Classics:

- May 1/2, 1961 Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 2

- May 1/2, 1961 Sergei Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 2

- November 1/4, 1961 Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 1

- November 1/4, 1961 Richard Wagner: Selections from Der Ring des Nibelungen

- November 1/4, 1961 Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 7

- April 30/May 2, 1962 Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 3, Tragic Overture

- April 30/May 2, 1962 Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 4, Leonore Overture No. 3

- April 30/May 2, 1962 Franz Schubert: Symphony No. 3

- April 30/May 2, 1962 Franz Schubert: Symphony No. 8

- April 29/May 1, 1963 Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3, "Eroica"

- April 29/May 1, 1963 Richard Wagner: Preludes and Overtures

- April 29/May 1, 1963 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 4

- April 27/29, 1964 Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 2

- April 27/29, 1964 Giuseppe Verdi: String Quartet in E (arr. Steinberg)

- April 27/29, 1964 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Nutcracker Suite

- June 7/9, 1965 Johannes Brahms: Symphony No. 4

- June 7/9, 1965 Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5

- June 7/9, 1965 Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 6

- April 4/8, 1966 Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9

- April 4/8, 1966 Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 8

- April 4/8, 1966 Igor Stravinsky: Petrushka

- May 15, 17, 18, 1967 Maurice Ravel: Valses nobles et sentimentales

- May 15, 17, 18, 1967 Antonín Dvořák: Scherzo capriccioso

- May 15, 17, 18, 1967 Hector Berlioz: Rakoczy March

- May 15, 17, 18, 1967 Camille Saint-Saëns: French Military March

- May 15, 17, 18, 1967 Johann Strauss: Perpetual Motion, Tritsch-Tratsch Polka

- May 15, 17, 18, 1967 George Gershwin: Porgy and Bess - Symphonic Picture, An American in Paris

- May 15, 17, 18, 1967 Aaron Copland: Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid

- April 6-10, 1968 Dimitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 1

- April 6-10, 1968 Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 7, Overture in G Minor

- April 6-10, 1968 Robert Russell Bennett: The Sound of Music - Symphonic Picture, My Fair Lady - Symphonic Picture

Recordings made with the Boston Symphony Orchestra for RCA Victor:

- September 29, 1969 Franz Schubert: Symphony No. 9, D 944 The Great

- January 12, 1970 Camille Saint-Saëns: Danse macabre with Joseph Silverstein, violin

- January 12, 1970 Richard Strauss: Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, Op. 28

- January 19 and October 19, 1970 Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 6

- October 26, 1970 Paul Dukas: The Sorcerer's Apprentice

Unissued recordings made with the Boston Symphony Orchestra for RCA Victor:

- January 12, 1970 Igor Stravinsky: Scherzo fantastique, Op. 3; Scherzo a la Russe

- October 26, 1970 Felix Mendelssohn: Scherzo from Octet in E flat

Recordings made with the Boston Symphony Orchestra for DGG:

- September 28 and October 12, 1970 Gustav Holst: The Planets

- March 24, 1971 Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30

- October 4/5, 1971 Paul Hindemith: Symphony: Mathis der Maler

- October 5, 1971 Paul Hindemith: Concert Music for Strings and Brass

Live recordings issued commercially:

- December 3, 1946 Dmitri Shostakovich: Symphony No. 7, "Leningrad" - Buffalo Philharmonic, Allegro Records (LP, sourced from concert performance given the day before the Musicraft recording of the work)

- September 10, 1965 Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 2, "Resurrection" - Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, ICA Classics

- December 19, 1969 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: "Don Giovanni" Overture - Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives Release

- February 26, 1972 Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 8 - Boston Symphony Orchestra, BSO From the Broadcast Archives 1943-2000

- June 15, 1973 Ludwig van Beethoven: Missa Solemnis - Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, ICA Classics

Video concert recordings issued commercially:

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 (October 6, 1970) & Symphony No. 8 (January 9, 1962); Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 55 (October 7, 1969) - Boston Symphony Orchestra, ICA Classics DVD

- Anton Bruckner: Symphony No. 8 (January 9, 1962) - Boston Symphony Orchestra, ICA Classics DVD

References

- ↑ Weschler, Lawrence (December 1996). "My Grandfather's Last Tale". The Atlantic Montly.

- ↑ "William Steinberg: Biography". MauriceAbravanel.Com. 2003-11-17. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ↑ "Relief Men". Time magazine. 1939-03-13. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- ↑ "Steinberg All Ready For Opener". The Pittsburgh Press. October 4, 1960. Retrieved 2013-03-16.

- 1 2 3 "Musical Great Steinberg, 78, Dies in N.Y.". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. May 17, 1978. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- ↑ "America's Symphonic Boom". Niagara Falls Gazette. December 19, 1971.

- ↑ Frederick P. Fellers, "The Metropolitan Opera on Record," Scarecrow Press, 2010.

- ↑ "EMI Classics Icon - William Steinberg". Retrieved 2012-02-09.

- ↑ "An End of an Era". New York Times. January 16, 1966.

- ↑ "Tape: Two Steinberg Releases". New York Times. February 18, 1962.

- ↑ "1962 Grammy Awards". Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ↑ "Spotlight on William Steinberg". Billboard. July 13, 1963.

- ↑ "Orchestra Records Bruckner, Broadway". The Pittsburgh Press. April 14, 1968.

- ↑ "Music Review". Buffalo Courier-Express. December 18, 1950.

- ↑ "Steinberg Awarded Mahler Medal". The Pittsburgh Press. April 6, 1956.

- ↑ "Toledoan New Life Fellow in International Institute". Toledo Blade. June 1, 1960.

- ↑ "Steinberg is Jaycees Man of Year". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 14, 1965. Retrieved 2012-06-01.

- ↑ "Symphony Attracts 1650; William Steinberg Honored". Indiana [Pennsylvania] Evening Gazette. February 22, 1956.

- ↑ "Wilson, Steinberg Win Degrees Rarely Given by Carnegie Tech". The Pittsburgh Press. June 13, 1954. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ↑ "Shriver Pep-Talks 760 Duquesne Grads". The Pittsburgh Press. June 1, 1964. Retrieved 2012-06-01.

- ↑ "Steinberg Gets Degree from Pitt". The Pittsburgh Press. February 26, 1966. Retrieved 2012-06-01.

- ↑ "A History of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra". Retrieved 2010-10-14.

- ↑ "Steinberg's Baton Gets Superb Results". New York Times. November 2, 1973.

- ↑ "Symphony Flutist Goldberg Yearns for Great, Old-Time Conductors". The Pittsburgh Press. June 24, 1984. Retrieved 2012-03-21.

- ↑ "Armando Ghitalla - Master Trumpeter, Master Teacher, Master Musician". International Trumpet Guild Journal. May 1997.

- ↑ "The Very Model of Musicianship". New York Times. March 3, 2002. Retrieved 2013-12-18.

- ↑ "Why Steinberg Gambles: 'Criticism I Get Anyway". Lewiston Morning Tribune. January 27, 1963. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ↑ "William Steinberg Conducts An All-Schoenberg Program". Boston Globe. November 21, 1965.

- ↑ David Schneider, "The San Francisco Symphony - Music, Maestros, and Musicians," Presidio Press, 1983.

- ↑ "A Leader of Equals". Time Magazine. September 11, 1964. Retrieved 2010-11-10.

- ↑ "Pittsburghesque". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. October 22, 1954. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

- ↑ "Quotes From the News". The Times-News. March 9, 1962. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- ↑ "William Steinberg: A Passionate Perfectionist". Oakland Tribune. August 8, 1976.

- ↑ "Interview with Klaus George Roy, Cleveland Orchestra Intermission feature". WCLV Broadcast. May 1973.

External links

- William Steinberg at AllMusic

- William Steinberg biography at the University at Buffalo

- William Steinberg and the Pittsburgh Symphony

- William Steinberg biography, anecdotes, and repertoire list

| Cultural offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Erich Leinsdorf |

Music Director, Boston Symphony Orchestra 1969-1972 |

Succeeded by Seiji Ozawa |