Harshaw, Arizona

| Harshaw, Arizona | |

|---|---|

| Populated Place | |

|

A sign marking the location of the Harshaw townsite. | |

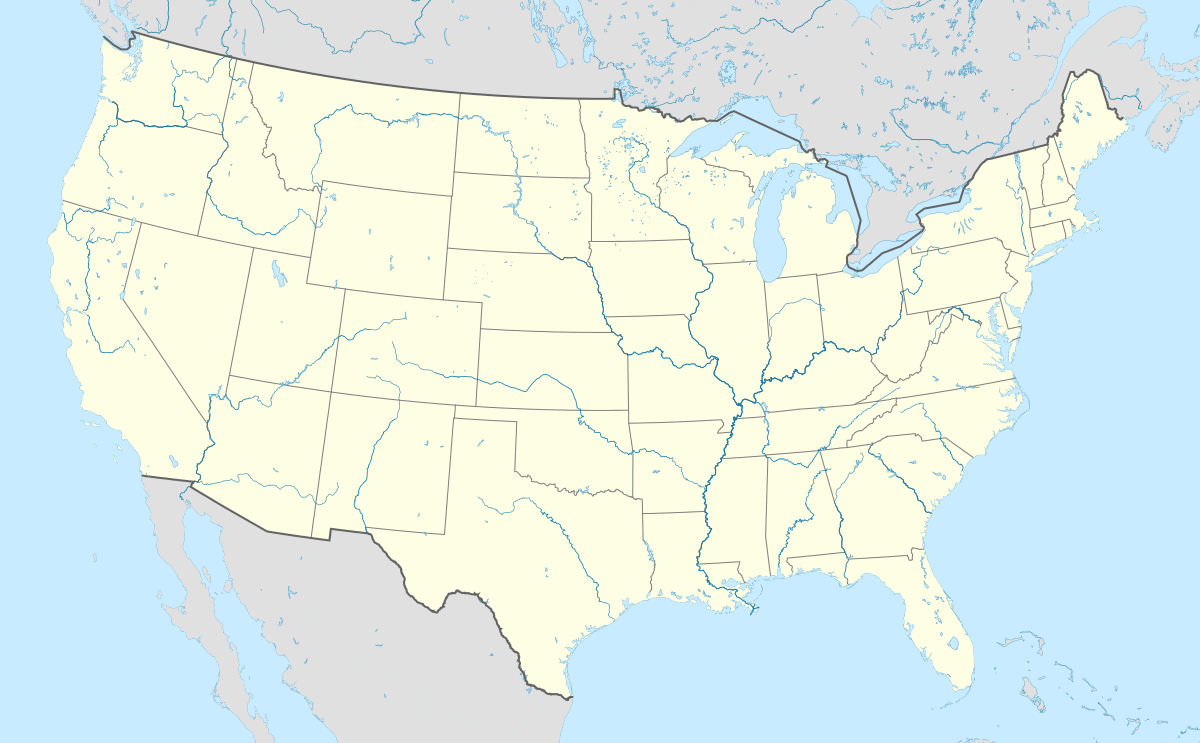

Harshaw  Harshaw Location in the state of Arizona | |

| Coordinates: 31°28′2″N 110°42′25″W / 31.46722°N 110.70694°WCoordinates: 31°28′2″N 110°42′25″W / 31.46722°N 110.70694°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Santa Cruz |

| Settled | 1873 |

| Founded | April 29, 1880 |

| Abandoned | 1960s |

| Founded by | David Harshaw[2] |

| Named for | David Harshaw[2] |

| Elevation[1] | 4,872 ft (1,485 m) |

| Population (2009) | |

| • Total | 0 |

| Time zone | MST (no DST) (UTC-7) |

| Post Office opened | April 29, 1880 |

| Post Office closed | March 4, 1903 |

| GNIS ID | 29768 |

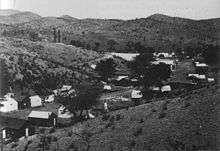

Harshaw is a populated place in Santa Cruz County in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Arizona. The town was settled in the 1870s, in what was then Arizona Territory. Founded as a mining community, Harshaw is named after the cattleman-turned-prospector David Tecumseh Harshaw, who first successfully located silver in the area.[2] At the town's peak near the end of the 19th century, Harshaw's mines were among Arizona's highest producers of ore, with the largest mine, the Hermosa, yielding approximately $365,455 in bullion over a four-month period in 1880.[3][4]

Throughout its history, the town's population grew and declined in time with the price of silver, as the mines and the mill opened, closed, and changed hands over the years. By the 1960s, the mines had shut down for the final time, and the town, which was made part of the Coronado National Forest in 1953, became a ghost town.[2][3][5][6]

Today, all that remains of Harshaw are a few houses, some building foundations, two small cemeteries, and dilapidated mine shafts. Most of the buildings were torn down by locals or by the Forest Service in the mid to late 1970s.[3][7][8]

History

Early settlement

The earliest known residents of what is now Santa Cruz County were the Apache, Yaqui and Hohokam Indians who settled on the banks of local waterways, including Harshaw Creek, in order to facilitate farming.[9] Spanish explorers and missionaries visited the area beginning in the 16th century, with the Spanish Friar Marcos de Niza, the first European to visit the area. In the late 17th century, Eusebio Kino came to the region to establish Jesuit missions and to map the land for Spain. It was not until 1752, in response to hostilities by the Pima Indians, that Spain established its first formal settlement and military presence in Arizona at Tubac on the Santa Cruz River northwest of the site of Harshaw.[9][10]

The accounts of Spanish missionaries who traveled through the area shortly after the founding of Tubac state that the site that was to become Harshaw was originally a Spanish settlement and ranch.[11] The settlement was known as Durazno, meaning "peach" or "peach orchard," supposedly due to the peach trees which had been planted there at some time in the past.[12][13][14] According to a missionary account from 1764, the settlement of Durazno was attacked and destroyed by Apache Indians on February 19, 1743, with significant loss of life. Along with the nearby Salazar ranch, which was also attacked on that day, the lives of 44 residents were lost.[11]

When the United States acquired all of present-day Arizona as part of the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, the numerous Mexican mining and ranching settlements still in existence became part of the United States, and American settlers moved into the area.[9][15]

Founding and early town history

David Harshaw was stationed in Tucson in the 1860s as a sergeant in the First Regiment of Infantry of the California Column. When he left the army, he returned to his previous occupation of ranching.[10][16][17] He had been ordered off of Apache land by Indian agent Tom Jeffords in early 1873 for illegal grazing, and he settled later that year in the area that was to become Harshaw, still known locally as Durazno, in order to find new pastures for his cattle.[2][3][8]

After a few years of prospecting in the region, Harshaw staked claims to several deposits of silver ore, one of which he sold to the Hermosa Mining Company around 1879.[2][3][18] In addition to digging and working what was to become the Hermosa mine, the company also began construction on a nearby twenty-stamp mill designed to process or "stamp" the silver ore into fine powder in preparation for smelting. The combined need for miners and mill workers caused the town to grow rapidly. The post office opened on April 29, 1880 under the name Harshaw in order to honor its founder. The Hermosa Mill commenced operations on August 5, 1880,[4][19] and the company soon employed approximately 150 people in the mine in addition to those working the mill.[2][3][8] At the town's peak, the mining and milling of silver was performed cheaper in Harshaw than in any other mining settlement in the Arizona Territory, and the mines were considered to be potential rivals of the productive Tombstone mines.[4]

Harshaw was soon home to some 200 buildings, 30 of them commercial, including eight or ten general stores, hotels, blacksmiths, stables, breweries, dance halls, and numerous saloons arrayed along its 3/4-mile (1.2 km) main road.[2][3][6] In addition to the mining industry, the town's merchants did a good trade with Sonora in Mexico as well as smaller regional mining camps.[20] Harshaw received mail service on the Southern Pacific Railroad via Tombstone three times a week,[20] and had its own newspaper, the Arizona Bullion, run by Charles D. Reppy and Company. The Bullion was launched on April 28, 1880, and had reached a circulation of 400 as of 1881.[2][21][22]

Harshaw was dealt a devastating blow when the Hermosa mine and mill both closed down in late 1881 due to a drop in the quality of silver ore extracted from the property.[2] Coupled with the Hermosa closures, severe thunderstorms which caused a large, damaging fire that same year almost put an end to the settlement.[3][8] Shortly thereafter, in 1882, The Tombstone Epitaph noted Harshaw's decline, and wrote that over 80% of the town's 200 buildings stood empty "with broken windows and open doors."[3][8]

Rebirth and subsequent decline

In 1887, Harshaw was reinvigorated when Tucson resident James Finley purchased the Hermosa mine for $600.[2][3][8] In addition to the rebirth of the mining industry, 1887 also saw the end of Apache raids in the area. The last recorded raid took place that year when 20 Indians raided Harshaw, resulting in the death of one man in an area mine.[6][16]

As of 1891, Harshaw was connected to the Arizona and New Mexico Railway lines, and had mail service three days a week. It still housed seven businesses, as well as a school and a hotel. In addition, David Harshaw's initial reason for coming to the area was still very much a factor in its use, as the land was noted for its exceptional grazing, and stock raising was second only to mining in area industries.[23] The Hardshell Mine that David Harshaw discovered in 1879 and sold to R. R. Richardson began to produce silver in 1896, further spurring the town's growth.[24] This smaller incarnation of the town continued until just around the start of the 20th century when the market price of silver declined, and mine owner James Finley died in 1903, closing the Hermosa mine again.[2][3] Most residents left the town and the post office closed on March 4, 1903.[2]

Continued activity

Despite a dwindling population, Harshaw gained some notice in 1906 when it was reported by the national press that Ben Daniels, one of Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders, was arrested for fraud associated with selling a Harshaw district mine to a business associate for $800, even though Daniels had no ownership of the property.[25]

In May 1929 when a forest fire swept through the Patagonia Mountains, Harshaw was reportedly down to 50 residents, all of whom were forced to evacuate, along with residents of other nearby mining camps. On May 13, 1929, after four days, and the burning of 15,000 acres (61 km2; 23 sq mi), the fire was contained, and the blaze was extinguished just in time to spare Harshaw from destruction as it had been directly in the path of the fire.[26][27]

The town again saw activity between 1937 and 1956 when the Arizona Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) worked the Flux and Trench mines located nearby,[3] and tapped into the region's non-silver ore.[28] After 1956, when ASARCO left, Harshaw returned to its status as a ghost town.[2][3]

In 1963, Harshaw ran afoul of the U.S. Forest Service. By this time, the town housed about 70 inhabitants, and consisted mostly of collapsed buildings, abandoned cars, and run down shacks. The only well-maintained structures in town were the Roman Catholic Church, and a small school.[6][16] The borders of the Coronado National Forest, established on July 1, 1953,[5] included the town of Harshaw, and because most of the residents never actually gained titles to their land, which could have been done starting in the 1880s, the government's property included the town.[29] Because no titles existed, and the land was then owned by the federal government, the residents were labeled as squatters. Further, once the National Forest was formed, obtaining titles to the land was no longer an option. Harshaw's rundown landscape proved to be an irritant to the Forest Service who, in 1963, tried to work with the residents to facilitate a plan to relocate the remaining families and clean up the town site.[6][16] The relocation efforts were not successful, however, as a few residents remained in Harshaw at least into the 1970s.[2]

Remnants

Several historic buildings remain in Harshaw, although most are on private property belonging to the Hale Ranch.[30] The most prominent building still standing is the James Finley House, now preserved and listed on the National Register of Historic Places as of November 19, 1974. Built around 1877 as a residence for the superintendent of the Hermosa Mine, the house was located just 100 yards (91 m) from the Hermosa Mill. When the mine was later purchased by James Finley, he took up residence in the house. The house is important historically as one of the few remaining buildings from Harshaw's mining heyday, and architecturally as a representation of period building styles in Arizona Territory. Notably, the house is of red brick construction rather than the adobe brick used in most other period buildings.[31][32]

Other remains at the site include the foundations of the Hermosa Mill, an assay office, a small church, a two-room schoolhouse, the remains of an adobe house/pool hall located on the outskirts of town, and two small cemeteries. Several other partial wood and adobe structures, as well as scattered mining remnants, are also located throughout the area. Of the remains, the cemeteries and the nearby adobe ruin are most easily accessible, as they are on the side of Harshaw Road, today designated as Forest Route (FR) 49.[3][7][8][31]

As of 2009, efforts are underway by the Center for Desert Archaeology to have the Santa Cruz Valley, including the remains of Harshaw, declared a National Heritage Area.[31]

Geology

The 5 miles (8.0 km) wide Harshaw Mining District is a rough and rugged landscape of numerous gulches,[33] with areas of lush forests and grasslands[8][34] interspersed with areas of exposed rock and jutting mountains.[34] It is bordered by the Patagonia District to the south, the main ridge of the Patagonia Mountains to the west, Meadow Valley Flat at the north end of the San Rafael Valley to the east, and Harshaw Creek to the northeast.[33]

The bedrock of the district is made up of at least five rock types, the most prevalent of which are composed of porphyritic, tridymite-bearing rhyolite. Where unoxidized the rhyolite contains abundant pyrite, chalcopyrite and chalcocite. Old workings and prospects are scattered throughout the outcrop area. Rhyolite formations include a wide swath across the northern section of the district, a section along the western border of the district, and almost all of Red Mountain, so named due to the color caused by the oxidation of the iron in the region's mineral deposits. The next most common bedrock is Cretaceous andesite[35] mainly present in lava flows and tuffs in low-lying areas underlying the rhyolite and overlying the older sediments. Andesite formations include a circular area just north of Harshaw, and a belt extending northward along Patagonia Road for about 3 miles (4.8 km).[33]

In smaller areas, the bedrock is a narrow, 3 miles (4.8 km) long strip of quartz diorite running from the southeast of Harshaw northwestward to Alum Canyon, a narrow belt of granite porphyry beneath deposits of rhyolite along the western border, and Paleozoic limestone in a small east-west belt along the middle part of the southern border of the district. In addition, Quaternary period gravel deeply covers the underlying bedrock in two areas in the northeast and southwest borders of the district.[33]

Mineral deposits are varied, with the andesite and rhyolite yielding surface deposits of silver, as well as zinc, lead, copper, and small amounts of gold, and the limestone containing deposits of manganese-silver ore. In addition, there are a few small, low grade placer gold deposits scattered throughout the area.[33] The two silver lodes associated with the Hermosa Mine are fault breccias embedded in rhyolite dating back to the Triassic or Jurassic period. The two lodes intersect at some depth below 330 feet (100 m), and runs to a depth of at least 500 feet (150 m). The ore mineral, cerargyrite, is located in a gangue of quartz with hematite, psilomelane, and limonitic material. The veins are of irregular and varying widths, which is a negative factor in mining.[18]

Mining

The Hermosa Mine was the largest ore producer in the area during the last decades of the 19th century, processing 75 short tons (68 t) of ore per day,[36] and peaking at about $365,455 in ore production over a four-month period in 1880.[3] Mine works at the Hermosa are extensive, with a total tunnel length of 7,000 feet (2,100 m) by 1915, including five levels of tunnels descending 500 feet (150 m). As of a 1972 survey, the existing works were actively caving in, rendering them not viable for further mining use.[18]

Local ore was plentiful, and other mines sprung up in the area around the town throughout the 1880s and 1890s. Some of the mines closest to Harshaw included the Bender, Alta, Salvador, Black Eagle and American mines.[37] Today, the Hardshell property, which includes many of the original mines from the 19th century, encompasses an area of approximately 3,154 acres (12.76 km2; 4.928 sq mi), including eight patented claims. From 1896 through 1964, mine production across all Hardshell property mines amounted to approximately 280,000 troy ounces (310,000 oz; 8,700,000 g) of silver.[37]

Including the Hardshell property, the area in and around Harshaw, known today as the Harshaw District, is home to approximately 50 mine sites, some dating back to the 1850s, and others mined during the early- to mid-1900s. In addition to silver, the area is rich in numerous other minerals, including zinc, copper, manganese, rhyolite, quartz, lead, and many others. Through the mid-1960s, total production from the Harshaw District mines included 86,000 short tons (78,000 t) of zinc, 72,000 short tons (65,000 t) of lead, 9,200,000 troy ounces (10,100,000 oz; 290,000,000 g) of silver, 3,100 short tons (2,800 t) of copper and 4,300 troy ounces (4,700 oz; 130,000 g) of gold.[33]

As of 2006, interest in mining the area resurfaced when the Canadian Wildcat Silver Corporation acquired an 80% share in the Hardshell property and began feasibility assessments.[38][39] Initial reports, published in 2007, were positive, and tentative plans called for the annual production of 2,750,000 troy ounces (3,020,000 oz; 86,000,000 g) of silver, 12,600,000 pounds (5,700,000 kg) of zinc, 670,000 pounds (300,000 kg) of copper, and 84,400,000 pounds (38,300,000 kg) of manganese over an expected productive life for the mine of 13.5 years.[40] A 2009 assessment also included lead among the expected products of the mine.[41] Wildcat is currently assessing a plan to construct an on site mill capable of processing 1,500 short tons (1,400 t) tons of ore per day.[40]

Similar assessments are underway in other nearby parts of Santa Cruz County, which historically accounted for one percent of the state's mining production by weight, and ten percent of the state's total lead and zinc production. Some residents are opposed to restarting mining operations as they are concerned about the impacts on the environment, on property values, on the tourist trade, and on traffic. Assessments are ongoing.[42]

Geography

.jpg)

Harshaw is located on the northern fringe of the Patagonia Mountains[20][23] at 31°28′2″N 110°42′25″W / 31.46722°N 110.70694°W (31.4673182, -110.7070290), northeast of Nogales, Arizona. The town lies within the borders of the Coronado National Forest, on United States government land,[6][16] approximately 15 miles (24 km) north of the Mexican border[1] and approximately 70 miles (110 km) south–southeast of Tucson.[20] The Hermosa Mine is located at 31°27′22″N 110°42′33″W / 31.45611°N 110.70917°W,[45][46] and the Hardshell Mine, the region's other top producer which rivaled the Hermosa during the last two decades of the 19th century, is located at 31°27′29″N 110°42′51″W / 31.45806°N 110.71417°W.[4][24][47]

At its peak in the 1880s and 1890s, Harshaw's location was considered scenic as it was surrounded by oak forests, lush pastures, and enough pure mountain water to adequately run the mill and work the ore.[4][20][23] Today, Harshaw Creek is lined with sycamores, cottonwoods, and willows which are typical foliage in more arid riparian zones,[8][34] as well as enough grass to sustain limited cattle grazing.[34] While the waters of Harshaw Creek still flow, they are no longer as pure as they were in the 19th century, as recent studies conducted in compliance with the Clean Water Act have found high levels of copper and zinc, as well as high acidity in the creek. While several factors likely contributed to this pollution, mining and milling residue from waste dumps have been identified as the most significant source. In particular, the waste dump of the abandoned Endless Chain Mine, which is located near the headwaters of Harshaw Creek, is one of the largest contributing factors in the pollution.[18][34]

Climate

The climate in the Harshaw Creek basin includes sub-zero temperatures and freezing precipitation in the winter, with snow accumulations at higher elevations sometimes lasting for several weeks, while summer frequently brings severe thunderstorms. Due to Harshaw's status as a ghost town, there is no local weather station, and the nearest stations at Canelo Pass and the San Rafael Ranch, and Nogales are not representative of the weather in Harshaw due to significant differences in environmental factors, such as differing elevations and their various locations relative to mountains.[34]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 640 | — | |

| 1890 | 260 | −59.4% | |

| 1910 | 150 | — | |

| 1920 | 377 | 151.3% | |

| 1930 | 259 | −31.3% | |

| 1940 | 150 | −42.1% | |

| 1950 | 100 | −33.3% | |

| 1960 | 0 | −100.0% | |

| Source:[48] | |||

Although by some accounts the town grew to 2,000 residents by 1881 at the peak of its mining prosperity, the fact that the town was already in decline a few years later along with the timing of population data collection makes that theory difficult to document.[3][28][49]

According to US Census data, the population of Harshaw reached its recorded peak of 640 residents in 1880, shortly after its founding. However, the closing of the Hermosa mine and mill coupled with the damage done from storms and fires between 1881 and 1882 caused the population to plummet to an estimated 150 in 1884.[48] The small resurgence of the late 1880s drove the population back up to 260 by 1890, before the town entered a steady decline culminating with its abandonment in the 1960s.[48] From 1960 on, the census no longer recorded any population for Harshaw,[48] although approximately 70 residents remained as of 1963,[6][16] and a few reportedly lasted into the 1970s.[2]

See also

- American Old West

- Boomtown

- History of Arizona

- List of ghost towns in Arizona

- Silver mining in Arizona

References

- 1 2 3 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Harshaw

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Sherman, James E.; Barbara H. Sherman (1969). "Harshaw". Ghost Towns of Arizona (First ed.). University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 0-8061-0843-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Varney, Philip (April 2005). "Santa Cruz Ghosts". In Stieve, Robert. Arizona Ghost Towns and Mining Camps: A Travel Guide to History (10th ed.). Phoenix, Arizona: Arizona Highways Books. pp. 109–110. ISBN 1-932082-46-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gleed, Charles Sumner (1882). From river to sea: a tourists' and miners' guide from the Missouri River to the Pacific Ocean via Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and California. Rand, McNaly. pp. 143–151. Retrieved September 28, 2009.

- 1 2 Davis, Richard C. (September 29, 2005). National Forests of the United States (PDF). The Forest History Society. p. 14. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Town Is a Squatter in National Forest". Fredericksburg, VA: Free-Lance Star. July 24, 1963. p. 12. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- 1 2 "United States Geological Survey Circular 1103-A: Harshaw Townsite and Cemetery". United States Geological Survey. 1994. Retrieved 2014-12-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Massey, Peter; Wilson, Jeanne (April 24, 2006). "Along the Trail". Backcountry Adventures Arizona: The Ultimate Guide to the Arizona Backcountry for Anyone With a Sport Utility Vehicle. Adler Publishing Co. pp. 40, 506. ISBN 1-930193-28-9. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Santa Cruz County: History". Santa Cruz County (www.co.santa-cruz.az.us). 2003. Retrieved September 30, 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - 1 2 De Long, Sidney Randolph; Arizona Pioneers' Historical Society (1905). The history of Arizona: from the earliest times known to the people of Europe to 1903. The Whitaker & Ray company. pp. 161–166. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- 1 2 Nentvig, Juan; Pradeau, Alberto Francisco; Rasmussen, Robert R. (1980). Rudo Ensayo: A Description of Sonora and Arizona in 1764. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-8165-0696-5. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- ↑ Bigelow, John (1968). On the bloody trail of Geronimo. Westernlore Press. p. 227. ISBN 0-87026-016-2. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- ↑ Voices from the Pimería Alta. Nogales, AZ: Pimería Alta Historical Society. 1991. p. 114. ISBN 0-9617061-1-2. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- ↑ Federal Writers' Project (1940). Arizona The Grand Canyon State A State Guide. US History Publishers. p. 395. ISBN 1-60354-003-2. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- ↑ Farish, Thomas Edwin (1916). History of Arizona, Volume 3. The Filmer brothers electrotype company. pp. 226–231. Retrieved September 30, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Town a Squatter in Forest". Eugene, OR: Eugene Register-Guard. July 4, 1963. p. 8. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ↑ Congressional serial set. United States. Government Printing Office. 1897. pp. 367–368, 1213. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Chatman, Mark L. (1994). Mineral Appraisal of Coronado National Forest, Part 7: Patagonia Mountains-Canelo Hills Unit, Cochise and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona (PDF). Denver, CO: U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Mines. pp. A44, A120–A121. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Engineering and mining journal". Engineering and mining journal. Western & Co. 30: 114. 1880. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hamilton, Patrick (1881). The resources of Arizona: its mineral, farming, and grazing lands, towns, and mining camps : its rivers, mountains, plains, and mesas : with a brief summary of its Indian tribes, early history, ancient ruins, climate, etc., etc. : A manual of reliable information concerning the Territory. Arizona: Arizona Legislative Assembly. pp. 32, 42, 97. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ↑ Ayer Press. (1881). Ayer directory of publications. Ayer Press. p. 598. ISBN 0-910190-15-1. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ↑ "About this Newspaper: Arizona bullion.". Chronicling America. Library of Congress. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Report on the internal commerce of the United States. United States Treasury Dept., Bureau of Statistics. 1891. p. 80. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- 1 2 "Hardshell Mine (Manto Mine; Eagle-Picher|Eagle-Picher properties), Hardshell Gulch, Harshaw, Harshaw District, Patagonia Mts, Santa Cruz Co., Arizona, USA". MineDat.org. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ↑ "BEN DANIELS ARRESTED.; President's Arizona Appointee as Marshal Now Accused of Fraud.". New York, NY: New York Times. February 17, 1906. p. 1. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Forest Fire Perils Camps in Arizona". Milwaukee, WI: Milwaukee Journal. May 12, 1929. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Today in Arizona history". Arizona Daily Star. May 13, 2005. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- 1 2 Norman, Bill (November 24, 2005). "Discover Arizona's frontier mining past". Phoenix, AZ: East Valley Tribune. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ↑ "Ghost town haunts government". Reading Eagle. Jul 7, 1963. p. 6. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Barr, Betty (2006). Hidden Treasures of Santa Cruz County. BrockingJ Books. ISBN 0979026105.

- 1 2 3 "Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area Feasibility Study". Center for Desert Archaeology. April 2005. pp. 136, 223. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places". Record: 154725: National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-10-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Harshaw District, Patagonia Mts, Santa Cruz Co., Arizona, USA". MineDat.org. Retrieved October 23, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Scalamera, Robert J. (June 30, 2003). "Total Maximum Daily Load For: Upper Harshaw Creek, Sonoita Creek Basin, Santa Cruz River Watershed, Coronado National Forest, near Patagonia, Santa Cruz County, Arizona" (PDF). Arizona: Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, Water Quality Division. pp. 3–5, 14–17. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- ↑ Vikre, Peter G., et al., 2014, Succession of Laramide Magmatic and Magmatic-Hydrothermal Events in the Patagonia Mountains, Santa Cruz County, Arizona, Economic Geology, v. 109, pp. 1667–1704 Abstract

- ↑ Florin, Lambert (1986). Ghost towns of the West. Promontory Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-88394-013-2. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- 1 2 "Mining Company and Property Database". Hardshell. Global InfoMine. 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ↑ "Mining Company and Property Database". Hardshell: Reported Ownership. Global InfoMine. 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Mining Company and Property Database". Hardshell: Property News. Global InfoMine. July 6, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- 1 2 "Wildcat Silver Releases Preliminary Assessment Report - 53.6 Million Ounces Contained Silver" (PDF). Wildcat Silver Corp. Press Release. Global InfoMine. February 13, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Wildcat Silver Improves Processing at Hardshell" (PDF). Wildcat Silver Corp. Press Release. Global InfoMine. November 24, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ↑ Davis, Tony (March 12, 2007). "Mining firms eye prospects in Santa Cruz County". Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ "History: Pima County". Pima County Justice Court (jp.pima.gov). September 27, 2000. Retrieved September 30, 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Santa Cruz County". Arizona State Library Archives and Public Records: Arizona History and Archives Division (lib.az.us). August 4, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ "Hermosa Mine, Hermosa group, American Peak, Harshaw District, Patagonia Mts, Santa Cruz Co., Arizona, USA". MineDat.org. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hermosa Mine

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Hardshell Mine

- 1 2 3 4 Moffat, Riley (1996). Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc. pp. 9–17. ISBN 0-8108-3033-7.

- ↑ Kreutz, Doug (December 31, 2006). "One Man's Gift". Tucson, AZ: Arizona Daily Star. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Harshaw, Arizona. |

- Harshaw at Ghosttowns.com

- Patagonia Back Road Ghost Towns including Harshaw at LegendsofAmerica.com.

- Ghost Town of the Month, with an entry for Harshaw including recent photos and visitor information.

- Harshaw photos on Flickr.

- Harshaw at Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project.