History of transportation in New York City

Transportation in New York City has ranged from strong Dutch authority in the 17th century, expansionism during the industrial era in the 19th century and half of the 20th century, to cronyism during the Robert Moses era. The shape of New York City's transportation system changed as the city did, and the result is an expansive modern-day system of industrial-era infrastructure. New York City, being the most populous city in the United States, has a transportation system which includes one of the largest subway systems in the world; the world's first mechanically ventilated vehicular tunnel; and an aerial tramway.

Early days

Portions of Broadway were once a part of a primary route of the Lenape people in Pre-Dutch New York.[1] In the 18th century, the principal highway to distant places was the Eastern Post Road. It ran through the East Side, and exited out of what was the northernmost point of Manhattan, in present-day Marble Hill. Bloomingdale Road, later called Western Boulevard and now Broadway, was important for the West Side. According to Homberger, present-day Lafayette Street, Park Row, and St. Nicholas Avenue also follow former Lenape routes.[2] According to Burrow, et al.,[1] the Dutch had decided that that Lenape trail which ran the length of Manhattan, or present-day Broadway, would be called the Heere Wegh. The first paved street in New York was authorized by Petrus Stuyvesant (Peter Stuyvesant) in 1658, to be constructed by the inhabitants of Brouwer Street (present-day Stone Street).

Lenape trail routes were not only in Manhattan. Jamaica Avenue, which connects the present-day boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, also runs along a former trail through Jamaica Pass.

The early Dutch city of Nieuw Amsterdam (New Amsterdam) took full advantage of the rivers which surrounded the city, foreshadowing the empire that New York's shipping industry would establish two centuries later. According to the Castello Plan, multiple canals and waterways were built, including a very early canal on the present-day Broad Street, which was called the Heere Gracht. According to Burrows, et al.,[1] a municipal pier was built on what is now Moore Street, on the East River. The first regional ground transportation that was built out of Nieuw Amsterdam was a "wagon-road" that linked to Nieuw Haarlem (Harlem). It was built in 1658 to encourage development of that town, by order of Petrus Stuyvesant, who saw that Nieuw Haarlem could provide an important measure of defense for Nieuw Amsterdam.

19th century

The Province of New-York greatly improved the old Indian trails that had served the colony's earlier masters. Country roads suitable for wagons included the King's Highway in Kings County, two Jamaica Roads through Jamaica Pass, and Boston Post Road.

As new streets were laid out beyond Wall Street, the grid became more regular. The river areas being more useful, their streets were first, with streets parallel and perpendicular to their particular river. Later 18th-century streets in the middle of the island were even more regular, with city blocks longer in the approximately north/south direction than east/west. By the early 19th century, inland urban growth had reached approximately the line of the modern Houston Street, and farther in Greenwich Village. Due to expanding world trade, growth was accelerating, and a commission created a more comprehensive street plan for the remainder of the island.

New York adopted a visionary proposal to develop Manhattan north of 14th Street with a regular street grid, according to "The Commissioners' Plan of 1811." This would fundamentally alter the city aesthetically, economically, and geographically. The economic logic underlying the plan - which called for twelve numbered avenues running approximately north and south, and 155 orthogonal cross streets - was that the grid's regularity would provide an efficient means to develop new real estate property and would promote commerce.

Into the middle 19th century most streets remained unpaved, but tracks allowed smooth public transport by horse cars which were eventually electrified as trolleys. The 1854 Jennings streetcar case abolished racial discrimination in public transit.

Water transport

Water transport grew rapidly in the new century, due in part to technical development under Robert Fulton's steamboat monopoly. Steamboats provided rapid, reliable connections from New York Harbor to other Hudson River and coastal ports, and later local steam ferries allowed commuters to live far from their workplaces. The completion in 1825 of the upstate Erie Canal, spanning the Hudson River and Lake Erie, made New York the most important connection between Europe and the American interior. The Gowanus Canal and other works were built to handle the increased traffic, all suitable existing shorelines having already been lined with docks. The Morris Canal and Delaware and Raritan Canal were parts of the extensive system of new infrastructure serving the city with coal and other commodities. The canal age, however, gave way to a railway age.

New Yorks' ports continued to grow rapidly during and after the Second Industrial Revolution, making the city America's mouth, sucking in manufactured goods and immigrants and spewing forth grains and other raw materials to the developed countries. By the mid-19th century, thanks in part to the introduction of oceanic steamships, more passengers and products came through the Port of New York than all other harbors in the country combined. Conversion to steam brought a large fleet of distinctive New York tugboats.

Streetcars found steam power impractical, and more often progressed directly from horse power to electricity. Suburban electrification involved true trolley cars, but the required overhead wires were forbidden in New York (Manhattan). Traffic congestion and the high cost of conduit current collection impeded streetcar development there.

New York's waterways, so useful in establishing its commerce and power, became obstacles to railroads. Freight cars had to be carried across the harbor by car floats, contributing to harbor traffic already made heavy when many of the great new ocean steamships of the day must be served by lightering due to insufficient dock slips large enough to accommodate them despite the expensive Chelsea Piers.

The Harlem River being not so difficult, three railroads with service to the north agreed to build a common Grand Central Terminal, but disagreement among New Jersey railroad companies foiled efforts to organize a great new rail bridge across the Hudson, so the Pennsylvania Railroad, with its newly acquired Long Island Rail Road subsidiary, built the New York Tunnel Extension for its new Pennsylvania Station, New York. Passengers of the other companies changed to the Pennsylvania, or continued to cross the Hudson by ferries and the Hudson Tubes.

The Gowanus Canal being too small to handle late 19th-century barges, Newtown Creek was similarly canalized, serving among other customers the newly translocated gas works of the newly amalgamated Brooklyn Union Gas company on the Whale Creek tributary. Refineries and petrochemical factories followed in later decades, greatly intensifying the industrialization of Greenpoint, Bushwick, Maspeth and other outlying former villages in the newly amalgamated City of Greater New York. Greenpoint remained a center of the fuel trade beyond the 20th century.

Workaday purposes were not the only ones pursued on the waters. Mark Twain's Innocents Abroad recounts one of the first cruise ship voyages out of Brooklyn in the 1860s for rich people, while the 1904 General Slocum disaster points out the late 19th- and early 20th-century habit of organizing day excursions for humbler folk. Some trips went to amusement parks or other attractions, and some merely to a dock with a footpath to a meadow for dancing, picnicking and other pleasures made more pleasurable by absence from the hectic, noisy city. Day-trippers visited the Great Falls of the Passaic River and other tourist attractions by railroad and sometimes by organized bicycle tours. Hudson River Day Line was the last company doing regularly scheduled day trips from West 42d Street; they went out of business in the 1970s.

Brooklyn Bridge

Designed by John Roebling, the Brooklyn Bridge was the first link between Manhattan and the land mass of Long Island. It was notable for size, magnificence and commercial importance. The main span of 1,596' 6" was the longest span of any bridge in the world when it was completed in 1883, a period of time that firmly established the concept of municipal consolidation among the outlying cities and suburbs into what eventually became the City of Greater New York.

The Brooklyn Bridge was opened for use on May 24, 1883. The opening ceremony was attended by several thousand people and many ships were present in the East Bay for the occasion. President Chester A. Arthur and Mayor Franklin Edson crossed the bridge to celebratory cannon fire and were greeted by Brooklyn Mayor Seth Low when they reached the Brooklyn-side tower. Arthur shook hands with Washington Roebling at the latter's home, after the ceremony. Roebling was unable to attend the ceremony (and in fact rarely visited the site again), but held a celebratory banquet at his house on the day of the bridge opening. Further festivity included the performance of a band, gunfire from ships, and a fireworks display.[3]

On that first day, a total of 1,800 vehicles and 150,300 people crossed what was then the only land passage between Manhattan and Brooklyn. Emily Warren Roebling was the first to cross the bridge. The bridge's main span over the East River is 1,595 feet 6 inches (486.3 m). The bridge cost $15.5 million to build (in 1883 dollars) and an estimated number of 27 people died during its construction.[4]

Other East River bridges, which would be built soon after, included the Williamsburg Bridge (1903),[5][6] the Queensboro Bridge (1909),[7] and Manhattan Bridge (1909).[8]

Subways

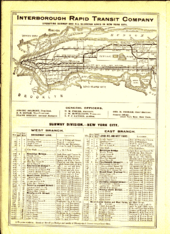

Steam railroads, started in places less generously endowed with waterways, soon reached New York and became a tool of the rivalry among port cities. New York with its New York Central Railroad came out on top, ensuring the city's continued dominance of the international trade of the interior of the United States. As the West and East sides of Manhattan became more populated, local railroads were elevated or depressed to escape road traffic, and the intercity railroads abandoned their Downtown Manhattan stations on Chambers Street and elsewhere. Soot and an occasional shower of flaming embers from overhead steam locomotives eventually came to be regarded as a nuisance, and the railroads were converted to electric operation. A competitive network of plank roads and surface and elevated railroads sprang up to connect and urbanize Long Island, especially the western parts.

New York was not the first to develop rapid transit in the United States, but soon caught up. Elevated trains, after a modest introduction on 9th Avenue, spread in the 1880s. Originally, elevated railways covered much of Manhattan and western Brooklyn.

The first elevated Manhattan (New York County) line was constructed in 1867-70 by Charles Harvey and his West Side and Yonkers Patent Railway company along Greenwich Street and Ninth Avenue (although cable cars were the initial mode of transportation on that railway). Later more lines were built on Second, Third and Sixth Avenues. None of these structures remain today, but these lines later shared trackage with subway trains as part of the IRT system.

In Brooklyn (Kings County), elevated railroads were also built by several companies, over Lexington, Myrtle, Third and Fifth Avenues, Fulton Street and Broadway. These also later shared trackage with subway trains, and even operated into the subway, as part of the BRT and BMT. Most of these structures have been dismantled, but some remain in original form, mostly rebuilt and upgraded. These lines were linked to Manhattan by various ferries and later the tracks along the Brooklyn Bridge (which originally had their own line, and were later integrated into the BRT/BMT).

In 1898, New York, Kings and Richmond Counties, and parts of Queens and Westchester Counties and their constituent cities, towns, villages and hamlets were consolidated into the City of Greater New York. During this era the expanded City of New York resolved that it wanted the core of future rapid transit to be underground subways, but realized that no private company was willing to put up the enormous capital required to build beneath the streets.[9][10]

The City decided to issue rapid transit bonds outside of its regular bonded debt limit and build the subways itself, and contracted with the IRT (which by that time ran the elevated lines in Manhattan) to equip and operate the subways, sharing the profits with the City and guaranteeing a fixed five-cent fare later confirmed in the Dual Contracts.[11]

20th century

Air transport

Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia promoted an airport in Brooklyn and two larger ones in Queens – one named after him, and one named after late President of the United States, John F. Kennedy. The Queens airports grew and prospered in later decades, but the Floyd Bennett Field eventually was closed to regular passenger service.

Automotive transport

John D. Hertz started the Yellow Cab Company in 1915, which operated hireable vehicles in a number of cities including New York. Hertz painted his cabs yellow after he had read a study that identified yellow as being the most visible color from a long distance.

In the late 1910s, Mayor John Francis Hylan authorized a system of "emergency bus lines" managed by the Department of Plant and Structures. These were eventually ruled illegal by the courts, and those that continued to operate obtained franchises from the city.[12]

The increased use of private automobiles greatly affected all transportation projects built more or less after 1930. In 1927, the Holland Tunnel, built under the Hudson River, was the first mechanically ventilated vehicular tunnel in the world. The Lincoln and Holland tunnels were built instead of bridges to allow free passage of large passenger and cargo ships in the port, which were still critical for New York City's industry through the early- to mid-20th century. Other 20th-century bridges and tunnels crossed the East River, and the George Washington Bridge was higher up the Hudson.

In 1967, New York City ordered all "medallion taxis" be painted yellow.[13]

Water transport

Early in the 20th Century the Department of Dock and Ferries built a series of piers south of 23rd Street to handle the ever-growing traffic of oceanic passenger steamships, which was later called Chelsea Piers.

Hudson River crossings were in the charge of the Port of New York Authority, which also took control of freight piers and built an Inland Freight Terminal in Lower Manhattan. The Port Authority oversaw the transition of the ocean cargo industry from North River break bulk operations to containerization ports, mostly on Newark Bay, built a Downtown truck terminal on Greenwich Street and Midtown bus terminal, and took over the financially ailing Hudson Tubes that carried commuters from Hudson and Essex Counties in New Jersey to Manhattan. Plans for a Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel to replace the declining car float operations of the railroads did not come to fruition; instead most land freight traffic converted to trucks. The Port Authority also took over and expanded the major airports owned by the Cities of New York and Newark, New Jersey.

During World War II, the New York Port of Embarkation handled about 44% of all personnel and 34% of all cargo shipped out to war.

Subways

The expansion of rapid transit was greatly facilitated by the signing of the Dual Contracts in 1913. Contract 3 was signed between the IRT and the City; the contract between the BRT and the City was Contract 4. The majority of the present-day subway system was either built or improved under these contracts,[11] which not only built new lines but added tracks and connections to existing lines of both companies. The Astoria Line and Flushing Line were built at this time, and were for some time operated by both companies. Under the terms of Contracts 3 and 4, the city would build new subway and elevated lines, and rehabilitate and expand certain existing elevated lines, and lease them to the private companies for operation. The cost would be borne more-or-less equally by the City and the companies. The City's contribution was in cash raised by bond offerings, while the companies' contributions were variously by supplying cash, facilities and equipment to run the lines.[11]

Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia presided over the construction of the Independent Subway System started by his predecessors. The City, bolstered by political claims that the private companies were reaping profits at taxpayer expense, determined that it would build, equip and operate a new system itself, with private investment and without sharing the profits with private entities. This led to the building of the Independent City-Owned Subway (ICOS), sometimes called the Independent Subway System (ISS), the Independent City-Owned Rapid Transit Railroad, or simply The Eighth Avenue Subway after the location of its premier Manhattan mainline. After the City acquired the BMT and IRT in 1940, the Independent lines were dubbed the IND to follow the three-letter initialisms of the other systems.[15] The original IND system, consisting of the Eighth Avenue mainline and the 6th Avenue, Concourse, Culver, and Queens Boulevard branch lines, was entirely underground in the four boroughs that it served, with the exception of the Smith–Ninth Streets and Fourth Avenue stations on the Culver Viaduct over the Gowanus Canal in Gowanus, Brooklyn.[15]

Construction of new subways came to a virtual standstill between the 1950s and the 2000s, with proposed expansions being first deferred and then scaled back.

The originally planned IND system was built to the completion of its original plans after World War II ended, but the system then entered an era of deferred maintenance in which infrastructure was allowed to deteriorate. In 1951 a half-billion dollar bond issue was passed to build the Second Avenue Subway, but money from this issue was used for other priorities and the building of short connector lines, namely a ramp extending the IND Culver Line over the ex-BMT Culver Line at Ditmas and McDonald Avenues in Brooklyn (1954), allowing IND subway service to operate to Coney Island for the first time, the 60th Street Tunnel Connection (1955), linking the BMT Broadway Line to the IND Queens Boulevard Line, and the Chrystie Street Connection (1967), linking the BMT line via the Manhattan Bridge to the IND Sixth Avenue Line.[16]

Soon after, the city entered a fiscal crisis. Construction (and even maintenance of existing lines) was deferred, and graffiti and crime were at all-time highs. Meanwhile, trains always broke down and were poorly maintained and often late, while ridership declined by the millions each year. Closures of elevated lines continued. These closures included the entire IRT Third Avenue Line in Manhattan (1955) and the Bronx (1973), as well as the BMT Lexington Avenue Line (1950), much of the remainder of the BMT Fulton Street Line (1956), the downtown Brooklyn part of the BMT Myrtle Avenue Line (1969) and the BMT Culver Shuttle (1975), all in Brooklyn.[17] Only a few parts of the massive, 1968-era Program for Action were ever opened: the Archer Avenue Lines and 63rd Street Lines were the only parts of the subway to open under the Program, having been inaugurated in the late 1980s.[18]

Robert Moses era

Mayor La Guardia appointed a dynamic young Robert Moses as Commissioner of Parks who, in the West Side Improvement, separated the freight service of the West Side Line (NYCRR) from street life, to the benefit of both and of parks. Later, Moses extended parkways beyond previous limits. After 1950 the federal government's priority shifted to freeways, and Moses applied his usual vigor to that kind of construction.

A catalyst for expressways and suburbs, but a nemesis for environmentalists and politicians alike, Robert Moses was a critical figure in reshaping the very surface of New York, adapting it to the changed methods of transportation after 1930. Beyond designing a series of limited-access parkways in four boroughs, which were originally designed to connect New York City to its more rural suburbs, Moses also conceived and established numerous public institutions, large-scale parks, and more.[19] With one exception, Moses had conceptualized and planned every single highway, parkway, expressway, tunnel or other major road in and around New York City; that exception being the East River Drive. All 416 miles of parkway were also designed by Moses. Between 1931 and 1968, seven bridges were built between Manhattan and the surrounding land, including the Triborough Bridge, and the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge. The Verrazano-Narrows Bridge connecting Brooklyn and Staten Island, was the longest suspension bridge in the world when it was completed in 1964. In addition, Moses was critical in designing several tunnels around the city; these included the Queens Midtown Tunnel, which was the largest non-Federal project in 1940, and the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel in 1950.

Late 20th century

In the 1960s the State took over two financially ailing suburban commuter railroads and merged them, along with the subways and various Moses-era agencies, into what was later named the MTA. In the 1970s, the modern New York Passenger Ship Terminal replaced the Chelsea Piers that were rendered obsolete by new, larger passenger liners.

21st century

Since the early 2000s, many proposals for expanding the New York City transit system are in various stages of discussion, planning, or initial funding. Some proposals will compete with others for available funding:

- In January 2007, the Port Authority approved plans for the $78.5 million purchase of a lease of Stewart Airport in Newburgh, New York as a 4th major airport for the area.[20]

- World Trade Center Transportation Hub, whose construction began in late 2005, will replace the temporary PATH terminal that replaced the one destroyed in the September 11 attacks. This new central terminal, designed by Santiago Calatrava, will allow easy transfer between the PATH system, several subway lines and proposed new projects. It is expected to serve 250,000 travelers daily when it opens on December 15, 2015.

- Fulton Center, a $1.4 billion project in Lower Manhattan that will improve access to and connections between 11 subway routes, PATH service and the World Trade Center site. Construction began in 2005, and it opened in November 2014.[21]

- Moynihan Station would expand Penn Station into the James Farley Post Office building across the street. The first phase has been fully funded.

- Second Avenue Subway, a new north-south line, first proposed in 1929, would run from 125th Street in Harlem to Hanover Square in lower Manhattan. The first phase, from 63rd Street to 96th Street, is under construction, and is scheduled to be opened to passenger service on December 30, 2016.

- 7 Subway Extension extended the 7 <7> trains west along 42nd Street from its then-terminus at Times Square, then south along 11th Avenue to the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center/Hudson Yards area at 34th Street station. Tunnel construction began in 2008, and operational service began on September 13, 2015.

- East Side Access project will route some Long Island Rail Road trains to Grand Central Terminal instead of Penn Station. Since many LIRR commuters work on the east side of Manhattan, many in walking distance of Grand Central, this project will save travel time and reduce congestion at Penn Station and on subway lines connecting it with the east side. It will also greatly expand the hourly capacity of the LIRR system. Completion is scheduled for 2015.

- The Lower Manhattan – Jamaica / JFK Transportation Project would extend the Atlantic Branch, an existing Long Island Rail Road line from Jamaica Station, with a new 3-mile (4.8 km) tunnel under the East River from downtown Brooklyn to Manhattan. AirTrain JFK-compatible cars would run along the new route, connecting John F. Kennedy International Airport and Jamaica with Lower Manhattan.[22][23][24] This project is still just a proposal, although it has the support of Mayor Michael Bloomberg.[25]

- Gateway Project will add a second pair of railroad tracks under the Hudson River, connecting an expanded Penn Station to NJ Transit and Amtrak lines. This project is a successor to a similar one called Access to the Region's Core, which was canceled in October 2010 by New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, citing the possibility of cost overruns and the state's lack of funds. Amtrak is now in charge of the project, which is currently under construction and slated to be completed by 2020.[26]

- Although New York City does not have light rail, a few proposals exist:

- There are plans to convert 42nd Street into a light rail transit mall that would be closed to all vehicles except emergency vehicles.[27] The idea was previously planned in the early 1990s, and was approved by the City Council in 1994, but stalled due to lack of funds. It is seen been opposed by the city government because it would compete with the 7 Subway Extension/IRT Flushing Line (7 <7> trains).[28]

- Staten Island light rail proposals have found political support from Senator Charles Schumer and local political and business leaders.[29]

- Brooklyn Historic Railway Association is also planning light rail in Red Hook, Brooklyn.[30]

- John F. Kennedy International Airport is undergoing a US$10.3 billion redevelopment, one of the largest airport reconstruction projects in the world. In recent years, Terminals 1,[31][32] 4,[33][34] 5,[35] and 8[36] have been reconstructed.

- Santiago Calatrava proposed an aerial gondola system, linking Manhattan, Governors Island, and Brooklyn, as part of the city's plans to develop the island.[37]

- As part of a long-term plan to manage New York City's environmental sustainability, Mayor Michael Bloomberg released several proposals to increase mass transit usage and improve overall transportation infrastructure.[38] Apart from support of the above capital projects, these proposals include the implementation of bus rapid transit, the reopening of closed LIRR and Metro-North stations, new ferry routes, better access for cyclists, pedestrians and intermodal transfers, and a congestion pricing zone for Manhattan south of 86th Street.

References

- 1 2 3 Burrows; et al. (1999). Gotham. Oxford Press. ISBN 0-19-511634-8.

- ↑ Homberger, Eric (1998). The Historical Atlas of New York City: A Visual Celebration of Nearly 400 Years of New York City's History. Henry Holt and Company, LLC. ISBN 0-8050-6004-9.

- ↑ Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 359–360. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

- ↑ "Brooklyn Daily Eagle 1841–1902 Online". Archived from the original on 2007-11-14. Retrieved 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Williamsburg Bridge". nycroads.com. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- ↑ "New Bridge in a Glory of Fire; Wind-Up of Opening Ceremonies a Brilliant Scene". The New York Times. December 20, 1903. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

- ↑ "Queensboro Bridge Opens to Traffic". The New York Times. March 31, 1909. p. 2. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ↑ Manhattan Bridge at Structurae

- ↑ Hood, Clifton. "Professor". 722 Miles. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ Hood, Clifton (1995). 722 Miles. The Johns Hopkins University Press; First Edition (September 1, 1995). p. 59. ISBN 978-0801852442.

- 1 2 3 "The Dual System of Rapid Transit (1912)". www.nycsubway.org. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "CITY'S BUS APPEAL IS DENIED BY COURT; ALL STOP TOMORROW; Hylan Calls Estimate Board in Effort to Get Special Session of Legislature. LEAVES SARATOGA TODAY Injunction, Granted by Justice Mullan, Upheld by Decision of Higher Tribunal. 2 SYSTEMS NOT AFFECTED Grand Concourse and Rockaway to Continue Operation Under Transit Board Franchises". Sunday New York Times. July 15, 1923. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ PBS and WNET (August 2001). "Taxi Dreams". Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ↑ Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NY-69, "New York State Barge Canal, Grain Elevator Terminal, Henry Street Basin, Brooklyn, Kings County, NY", 1 photo, 1 data page, 1 photo caption page

- 1 2 "History of the Independent Subway". www.nycsubway.org. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Board of Transportation - 1951". Thejoekorner.com. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ "The New York Transit Authority in the 1970s". www.nycsubway.org. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "The New York Transit Authority in the 1980s". www.nycsubway.org. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ Caro, Robert A. (1975). The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-72024-5.

- ↑ "Port Authority Authorizes Purchase of Operating Lease at Stewart International Airport" (Press release). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. January 25, 2007. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ↑ Ben Yakas (2014-11-09). "Photos: Your First Look At The Gleaming New Fulton Center Subway Hub". Gothamist. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Governor Pataki Announces Results of Joint Study on Lower Manhattan to Long Island and JFK Rail Link" (Press release). Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. 2004-05-05. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ↑ Urbina, Ian; Chan, Sewell (2005-03-12). "Rail Link to J.F.K. Airport Falls Short in the Financing". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ↑ "Lower Manhattan-Jamaica/JFK Transportation Project - Project Feasibility". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ↑ "Downtown needs a rail link to J.F.K. Airport". Downtownexpress.com. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ Karen Rouse (20 April 2012). "Amtrak rail project keeps right on rolling". NorthJersey.com. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Home page". vision42. The Institute for Rational Urban Mobility, Inc. 2000–2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "America's Invisible Trolley System". Newsweek.com. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Reality check for Staten Island's rail plans". SILive.com. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Imagining a Streetcar Line Along the Waterfront". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-03-10.

- ↑ "Aviation Projects". William Nicholas Bodouva and Associates. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ↑ "Terminal One Group website". Jfkterminalone.com. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ↑ Cooper, Peter (November 24, 2010). "John F. Kennedy Airport in New York Commences Terminal 4 Expansion Project". WIDN News. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ↑ "Delta opens new JFK Terminal 4 hub". Queens Chronicle. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ "New Hawaiian – JetBlue Partnership Brings Hawaii Closer to East Coast Cities" (Press release). JetBlue Airways. January 23, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ↑ "LAN Airlines Moves Into Terminal 8 at JFK With American Airlines" (Press release). American Airlines. January 31, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ↑ Josh Rogers (17–23 February 2006). "That's 125 million dollars, not lira for this island gondola". Downtown Express. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ Archived April 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.