History of the Galveston Bay Area

For a period of over 7000 years, humans have inhabited the Galveston Bay Area in what is now the United States. Through their history the communities in the region have been influenced by the once competing sister cities of Houston and Galveston, but still have their own distinct history. Though never truly a single, unified community, the histories of the Bay Area communities have had many common threads.

Prior to European settlement the area around Galveston Bay was settled by the Karankawa and Atakapan tribes, who lived throughout the Gulf coast region. Spanish and French explorers traveled the area for many years gradually establishing trade with the local natives. In the early 19th century the pirate Jean Lafitte created a small, short-lived empire around the bay ruled from his base on Galveston Island before his being ousted by the United States Navy.

Following Mexico's independence from Spain, the new nation established long-term settlements, including Anahuac and San Jacinto, around the bay. Early rebellions by the settlers against Mexican rule occurred in the region and it was later the site of the victory of the Texas army over the Mexican army during the Texas Revolution. Following Texas' independence from Mexico and its annexation by the United States, economic growth was centered initially on agriculture and cattle ranching. Commerce grew between Galveston, Harrisburg and Houston in the later 19th century, and created additional economic opportunities as railroads were built through the Bay Area to connect these and other commercial centers.

In the early 20th century the region gave birth to some of the state's earliest oil fields and refineries as the Texas Oil Boom took hold. Refining and manufacturing grew rapidly in the area, particularly around Baytown, Pasadena, and Texas City. The opening of the Port of Texas City, and later Barbours Cut and Bayport, gradually established the region as an important shipping center. As wealth increased in southeast Texas, resorts and other tourist draws developed in the Bay Area. During the 1960s the area became home of the Johnson Space Center, headquarters for the nation's manned space program, which helped diversify the regional economy and began the development of an aerospace industry, and later other high-tech industries.

Early history

The present geography of the Gulf Coast was formed during an ice age approximately 30,000 years ago when dramatic lowering of the sea level occurred.[1] As the ice later melted, it formed a flow through the Trinity and San Jacinto rivers and carved wide valleys in the soft sediments, resulting in the creation of the modern system of bays and lakes approximately 4500 years ago.[2]

Humans first entered the region as early as 10,000 years ago following migrations into the Americas from Asia during the ice age.[3] Research has indicated that the first settlements around Galveston Bay may have been constructed around 5500 BCE.[4] The first ceramics appeared around 100 CE, and arrow points around 650 CE.[5] When Europeans first entered the region there were still significant numbers of Native Americans living there.[6] Along the southern coast around the Colorado River and Matagorda Bay and up toward Galveston Bay lived the Capoque tribe, a branch of the Karankawa people.[7] The northeast was inhabited by the Akokisa, or Han, tribe as part of the Atakapan people's homelands.[8] The Karankawa were migratory hunter-gatherers. Their diet included deer, bison, peccary, and bears, in addition to fish, oysters, nuts, and berries as they were available. They used portable huts for shelter.[9] Dugout canoes were used to travel the many internal waterways and the coast, an advantage that initially gave them tactical superiority over the Europeans.[10] The Akokisa in the area were similarly hunter-gatherers, and utilized canoes for transport. They became well-known among the Europeans for their hide-tanning abilities, especially for bear hide.[11] During the 18th century the Akokisa population in the area was estimated at about 3500.[11]

Though earlier surveys of the coastline had been made, the first known Europeans to land in the vicinity were under the command of Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca when he and his crew were shipwrecked in 1528, though it is unclear precisely where they landed.[12] Though subsequent explorers described cannibalism among the local tribes, Cabeza de Vaca made no mention of the practice.[13] He and the other survivors left the area as soon as they were able traveling to safety into Mexico.[12]

The Rivas-Iriarte expedition, one of several Spanish maritime expeditions charting the Gulf Coast, performed a detailed scientific exploration of the Galveston Bay in 1687, probably the first such exploration.[14] A 1785 expedition by José Antonio de Evia charting the Gulf Coast gave the bay and the island the name Galveztown, or Galvezton, for the Spanish Viceroy Bernardo de Gálvez.[15]

During the early 18th Century, French traders first began trade with the Akokisa and the nearby Bidai tribes for furs.[16] In 1754 several traders including Joseph Blancpain established a trading post on the Trinity River a just north of the bay, near modern Wallisville. Spanish authorities quickly seized the post and transformed it into the San Augustín de Ahumada fort. They named the site El Orcoquisac and established a Catholic mission. The Spanish were not successful in maintaining trade with the natives and the post was abandoned within a few years.[17] Encroachment by Spanish as well as U.S. settlers continued such that by the end of the century native populations had declined dramatically due to disease and territorial pressures from the Europeans.[8]

In 1816 Galveston Island was claimed by the pirate Louis-Michel Aury as a base of operations to support Mexico's rebellion against Spain. Aury was succeeded as leader by Jean Lafitte, the famed Louisiana pirate and American hero of the War of 1812. Lafitte, at the time serving as a privateer for the Spanish Empire, transformed Galveston Island and the bay into a pirate kingdom he called Campeche. He established bases for smuggling and ship repair on the Trinity River near the bay and at Eagle Point (modern San Leon).[18][19] His gang also created a hide-out on the shores of Clear Lake. As late as 1965, treasure from this era was discovered at Kemah.[20] In response to the piracy, the United States Navy ousted Lafitte from the island in 1821 and the colony was abandoned.[21] Some settlers in the region remained such as Anson Taylor who had supplied produce and game from the Clear Lake area for Campeche.[22][23]

Mexican dominion and the Republic of Texas

.jpg)

In the early 19th century following the Louisiana Purchase, Texas, particularly southeastern Texas, had become an increasing point of contention between Spain and the United States. Various failed attempts, such as the Long Expedition, were made by groups from the U.S. to take control of parts of Texas, resulting in some temporary settlements near the bay including Perry's Point near modern Anahuac.[24] Spanish authorities began efforts to colonize Texas to help protect its claim to the territory. Hoping to spur settlement, the Spanish government granted land to pioneers from the United States, including Moses Austin.[25]

Soon afterward, though, Mexico declared its independence from Spain and moved to establish its own control over Texas. Because of fears of the indigenous tribes, officials found it difficult to find settlers in Mexico willing to move into the territory's coastal areas, and therefore continued to allow settlers from the United States into the area with the promise of allegiance to Mexico. Austin's son, Stephen F. Austin, established a colony which extended from east central Texas to Galveston Bay and the Gulf Coast. Some of Austin's original Old 300 settlers, including John Dickson, William Scott, and John Iiams, established homesteads and commercial enterprises around the bay.[26] The Port of Galveston and a permanent settlement were established on the island in 1825 to spur trade.[27] Communities including Lynchburg, San Jacinto, and Campbell's Bayou (founded by one of Lafitte's former officers) were gradually established around the bay. In addition to the Anglo-American and Mexican settlers in the area, a Cajun settlement was established along Armand Bayou.[28] The Mexican Colonization Law of 1824, however, forbade the creation of settlements near the coast with the intention of protecting the native tribes in the area.[29][30] The law was not enforced and settlers continued to encroach upon tribal lands.[31] Native tribes remained in the area years afterward but were gradually driven out as European settlers moved into the region.[30] The Akokisa were driven inland where they merged with the Bidai. The Karankwa were driven southward where they eventually established their current homelands in northeastern Mexico.[8]

The Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company was formed in New York in 1830 to promote additional settlement around Galveston Bay and other parts of southeast Texas.[32][33] The company gradually brought in many colonists from the United States and Europe, although conflict with Mexican officials over colonization laws initially made these efforts difficult.[32] In 1830, Mexican authorities created a customs and garrison post near the bay commanded by Juan Davis Bradburn.[34] The post, which later became the modern city of Anahuac, was the first major outpost on the mainland shores and temporarily replaced Galveston as a port of entry.[35] New Washington (modern Morgan's Point) and Austinia (within modern Texas City) were also founded by settlers from the company.[36] Conflicts between Bradburn and the settlers in the region over land rights, slavery laws, and customs duties led to the Anahuac Disturbances, a prelude to the larger Texas rebellion. As a result, Mexican authorities were driven out of eastern Texas and the settlers began to discuss independence.[37]

Following a coup in the Mexican government, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna became president and revoked many freedoms previously enjoyed by the Texans further deteriorating the government's relations with the region's settlers.[38] Texas declared its independence and revolted in 1835. Following a number of battles with the Mexican army, the Texas army, under the leadership of General Sam Houston, finally defeated Santa Anna in the Battle of San Jacinto, near modern Pasadena.[39]

The new Republic of Texas grew rapidly. The shores of the bay were initially home to farms and ranches. Longhorn cattle, which had roamed wild throughout Texas, became free resources for producing hides and beef shipped throughout North America. The famed Allen Ranch was established near Harrisburg in what is now southeast Houston and Pasadena, in addition to the Bay Lake Ranch and other ranches established around the bay.[40][41] The range land of these ranches came to encompass most of the terrain around the bay south of the San Jacinto River.[22][41] Cedar Bayou (part of modern Baytown), Shoal Point (part of modern Texas City), and other small communities began to develop during this period.[42][43] Eagle Point (part of modern San Leon) became an important shipping and trading post for slaves.[19]

Inland from the bay, the towns of Harrisburg and Houston were both founded on the Buffalo Bayou by entrepreneurs from New York and competed as commercial centers, but neither was as significant as Galveston.[44] Throughout the 19th century these three cities developed increasing influence on the Bay Area communities, particularly as railroads were built through the region.

Multiple hurricanes struck the region during this time and after. Though none during the 19th century were catastrophic, they nevertheless caused substantial damage and caused some loss of life.[45]

Annexation by the United States

Texas succeeded in its bid to join the United States in 1845, one of the key causes of the subsequent Mexican-American War. Texas' annexation brought more people to Texas. Ranching interests expanded around the bay, along with the growth of the farming and lumber enterprises in the region.[46] The construction of the Galveston, Houston and Henderson (GH&H) Railroad, begun in 1857, further spurred more growth in the region.[47][48]

During the American Civil War, in which Texas seceded from the United States, the area served a limited role in the conflict though no major battles were fought on the mainland shoreline. New fortifications, like Fort Chambers near Anahuac, were constructed to ward off a mainland invasion by Union forces and to protect supply routes to and from Galveston.[49] The GH&H Railroad was used in the recapture of Galveston by Confederate forces in 1863. Makeshift hospitals, such as the Nolan home in Dickinson, were established in the bayside communities.[47]

In the aftermath of the war the Texan economy declined for a period. Nevertheless, ranching interests became major economic drivers spawning many other economic enterprises like hide processing plants and shipping companies.[41][50] Some former slaves were able to take advantage of ranching's economic influence as some successful African American communities were established, including the "Settlement" in what is now League City.[51] The success of the various enterprises in the area and the growth of Galveston as one of the prime commercial centers in the South and Southwest helped promote the construction of the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway, and the La Porte, Houston and Northern Railroad over the course of the 19th century. These railroads built lines near the southwest shore of the bay and led to the creation of La Porte, Clear Creek (modern League City), Webster, Edward's Point/North Galveston (modern San Leon), and others (eventually including Texas City).[48][19] Toward the end of the century, as ranching's profitability declined, many communities turned increasingly to agriculture.[48] The farming community of Pasadena was established during this time.[52] By the end of the 19th century, the land south of Buffalo Bayou came to be known as the "Texas Fruit Belt" for the oranges, pears, grapes, and other fruits and vegetables grown in the area.[53] The Sylvan Beach park was created at La Porte as a beachfront summer getaway from Houston. With amenities including bathhouses, boating piers, and a Victorial hotel with a dance pavilion, Sylvan Beach quickly became the most popular tourist destination in the Houston area.[54][55]

In 1900 a massive hurricane devastated the city of Galveston and heavily damaged communities around the bay. According to some estimates the death toll on the coast outside of Galveston may have been over one thousand.[56] Bridges between Galveston and the mainland were destroyed.[57] Communities along the shoreline declined for some time as economic growth moved inland and Houston became the dominant economic center in Southeast Texas. The region received a population boost from some Galveston refugees who relocated to the mainland following the catastrophe.[58][59]

The wars and the oil boom

The sparsely populated communities around the bay transformed during the 20th century. Following the devastating 1900 hurricane, donations by the newly created Red Cross, including millions of strawberry plants to Gulf Coast farmers, helped revive area communities.[52] This and the subsequent establishment of a major strawberry farm in the area by Texaco founder Joseph S. Cullinan made Pasadena an important fruit producer for many years afterward.[22] The newly established community of Texas City opened its port and railroad junctions shipping cotton and grain.[60] In fact, because the port had opened just before the 1900 hurricane, it was able to handle Galveston's diverted shipping traffic until the island's damaged port was repaired.[43] Following another hurricane in 1915, the Texas City Dike was built to protect the Texas City ship channel from sediment movement in future storms, thus helping to build confidence in the safety of the port.[43][61] One of the most immediate effects of the dike, however, was to increase the salt levels in West Bay, between Galveston and the southwest coastline.[62]

Major tracts of the Allen Ranch were liquidated opening up new development around Pasadena and other bayside communities.[41] Commercial fishing for oysters and shrimp grew as a significant area industry.[63] The lumber industry also continued to grow.[48] A sugar refinery opened in Texas city, a paper mill in Pasadena, and other factories in the early 20th century.[43][52]

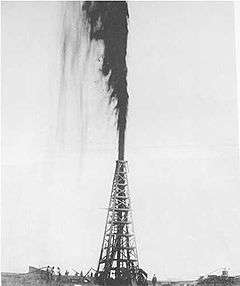

Following the petroleum discovery at Spindletop (roughly 40 miles (64 km) from Galveston Bay) in 1901 Texas entered an era of economic development known as the Texas Oil Boom. Petroleum exploration at Galveston Bay began shortly afterward with the discovery of the Goose Creek Oil Field in 1903.[64] The first well at Goose Creek was built in 1907 with significant production beginning in 1908 (in 1924 it was the state's third largest field).[65] In 1915 the first offshore oil drilling site in the state was opened at Goose Creek. Gradually other oil fields were discovered around the bay as well, including the Anahuac oil field in 1935.[66] The first refinery by the bay was built in 1908 at Texas City, followed by refineries in Baytown and Pasadena.[42][43][52] The main refinery in Baytown, built by Humble Oil (now ExxonMobil), became the largest in the state.[67]

The wealth brought on by the boom transformed the region. The population increased rapidly due to significant immigration from within the United States, from Mexico, and overseas. Mexicans, fleeing the Mexican Revolution in 1910, added significantly to the population of what is now Baytown; Sicilian immigrants added greatly to the community of Dickinson; and Japanese rice farmers settled in Webster, Pasadena, and League City[22][68][69][70] (in fact the rice industry on the U.S. Gulf Coast was born in Webster; see Seito Saibara).[71] Major manufacturing centers developed throughout the Bay Area with Houston acting as the corporate and financial center for the boom.[72] Wealthy Houstonians created waterfront retreats in Morgan's Point and a boardwalk amusement park at Sylvan Beach, La Porte (together known at the time as the Texas "Gold Coast"), as well as summer homes at Seabrook and other communities.[73][55] The onset of Prohibition made Galveston Bay an important entry point for smuggling illegal liquor, which supplied most of Texas and much of the Midwest. Boats arrived at locations ranging from Galveston to Seabrook.[74][75] The Maceo crime syndicate, which operated in Galveston at that time, created casino districts in Kemah and Dickinson and other areas of Galveston County. Houstonians often humorously referred to the county line as the "Maceo-Dickinson line" (a pun referring to the Mason-Dixon line).[76] Much of the area around Clear Lake was developed as recreational properties for the wealthy, including a large ranch estate owned by Houston businessman James West.[77] Though the Great Depression closed many businesses in the area petroleum-related growth helped offset the effects.[43]

During the World Wars, factories around the bay were pressed into service mass-producing a variety of products including aviation fuel, synthetic rubber, and ships.[78] The first tin smelter outside of Europe was opened in Texas City becoming one of the world's main suppliers.[43] The population in the Bay Area grew faster than even Houston as processing plants and factories were built and expanded.[79] Ellington Air Force Base was built to the southeast of Houston (adjacent to modern Clear Lake City) and became a major air field and flight training center during the wars.[80]

Industrialization and urbanization during the earlier 20th century led to the pollution of the bay. By the 1970s the bay was described by some sources as "the most polluted body of water in the U.S."[81] The ship channel and Clear Lake were rated by some sources as having even worse water quality.[81] Drilling for oil and underground water, as well as large wakes from increasing shipping in the bay, led to land subsidence and erosion along the shoreline, especially in the Baytown-Pasadena area.[82] Today approximately 100 acres (0.40 km2) of the historic San Jacinto battleground are submerged, most of Sylvan Beach is gone, and the once prominent Brownwood neighborhood of Baytown has had to be abandoned.[83]

In 1947, an explosion on a ship at the Port of Texas City caused fires and destruction throughout the city's industrial complex and other ships creating one of nation's worst industrial accidents. The tragedy caused more than five hundred deaths, more than four thousand injuries, and more than $50 million in damage ($531 million in today's dollars). Though the city's growth and prosperity were interrupted, the city and the business leaders were able to rebuild.[43]

Modern times

The war effort had brought about significant diversification in the area's industrial base.[43] This diversity facilitated the area's transition to a peacetime economy though the petroleum industry again became a major focus. In 1952 the Gulf Freeway, then part of U.S. Route 75, was completed providing a fast automobile link between Houston and Galveston.[84] The new freeway, considered an engineering marvel at the time, greatly encouraged new development in the western region of the bay.[85]

Hurricane Carla, Texas' largest storm on record, struck the coast in 1961 causing substantial flooding and damage in Texas City and other communities.[45] Loss of life was minimal thanks to evacuation efforts. Expansion of the flood control dike and construction on the Texas City seawall occurred a result. The project was completed in 1985.[43]

NASA's Johnson Space Center (JSC) was established in the area in 1963. That and the explosive growth of neighboring Houston in the mid-20th century, especially the 1970s and 1980s, caused the remainder of the communities on the southwestern shore to urbanize.[72] The Clear Lake City community was created by the Friendswood Development Company, a venture of Humble Oil and Dell E. Webb Corporation, to support residential growth near the new NASA facility.[50] The communities around Clear Lake rapidly reoriented toward aerospace related industries, and the region's economy diversified further. Urban development spread solidly between Houston and the Bay Area communities. Houston formally annexed most of Clear Lake City in 1977 with Pasadena annexing most of the rest.[50] Most of the other communities around the bay, however, had already incorporated, or incorporated soon afterward, and thus were independent of the metropolis.[77][86]

The economic boom of the 1970s and early 1980s that took place in Texas (because of the escalation in oil prices) benefited the Bay Area communities significantly. Industrial operations were expanded including the opening of the U.S. Steel plant in Baytown in 1970, and the Barbours Cut shipping terminal at Morgan's Point in 1977.[42][87] The Port of Texas City became the third leading port in Texas by tonnage and ninth in the nation.[43][88] The Barbours Cut terminal, operated by the Port of Houston, became the seventh leading port in the nation.[89] Not all of this development was without controversy, however. In building Barbours Cut, the Port of Houston used its power of eminent domain to evict residents from nearly one third of the homes in Morgan's Point.[90] Still, when the Texas economy declined in the later 1980s, the economic diversity of the area and substantial annual federal investments related to JSC helped the region fare better than most of Greater Houston.[50]

Conservation efforts in the mid to late 20th century by area industries and municipalities helped to dramatically improve water quality in the bay.[81] The Nature Conservancy and Houston's Outdoor Nature Club (ONC) helped encourage nature preservation efforts including creating the Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge, the Armand Bayou Nature Center, and the Texas City Prairie Preserve.[91][92][93] Tourism in the area grew, especially around Clear Lake, led in large part by the Space Center. Some former resort communities of the early 20th century like Kemah and Seabrook re-emerged. The lake itself today holds one of the largest concentrations of marinas in the world.[94]

During the later 20th century and afterward, many of the communities and businesses in the area began cooperative efforts, including the Clear Lake Area Chamber of Commerce, the Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership, and the Bay Area Houston Transportation Partnership, to create a distinct economic and civic identity for the region and to plan regional development.[95] Though most of the communities in the region have been incorporated into municipalities, a few unincorporated communities remain under the extra-territorial jurisdiction of neighboring towns. These include San Leon, Bacliff, and Smith Point. The communities of San Leon and Bacliff, despite their seaside location, their proximity to the relatively prosperous Clear Lake Area, and the development of summer resort communities there in the early 20th century, have suffered economic decline since the mid-20th century and are among the least affluent parts of the Bay Area today.[19][96][97]

In 2008 Hurricane Ike struck the coast causing substantial damage both environmentally and economically. As of 2009 the ecology of the region is still in recovery with damage caused by both natural pollution (sea salt) and man-made pollution (chemicals washed into the freshwater and the bay) still showing dramatic effects on both the marine and land-dwelling wildlife. Commercial fishing and oyster farming are expected to take decades to fully recover. Most major industry was able to return to normal operations but some tourist areas have taken longer to recover.[98]

Discussions of a proposal to build an Ike Dike that would protect the Bay Area, particularly the nationally critical Houston Ship Channel, were begun in 2009. As of 2010 the project is still in the conceptual stage.[99]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Description of Project Area". Texas A&M University: Galveston Bay Information Center. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ↑ "Geography". Galveston Bay Estuary Program. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- ↑ Wade, Mary Dodson (2008). Texas History. Coughlan Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 0-613-19100-5.

- ↑ Perttula 2004, p. 187

- ↑ Perttula 2004, p. 191

- ↑ Newcomb 1961, p. 59

Lipscomb, Carol A.: Karankawa Indians from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 14, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

Couser, Dorothy: Atakapan Indians from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 14, 2009. Texas State Historical Association. - ↑ Newcomb 1961, pp. 59–60

- 1 2 3 "Ethnohistory". Texas Beyond History. University of Texas. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ↑ Newcomb 1961, pp. 66–68

- ↑ Newcomb 1961, p. 67

- 1 2 "Akokisa Indian Village". Harris County Precinct 4. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- 1 2 Chipman, Donald E.: Cabeza de Vaca, Álvar Núñez from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical

- ↑ Himmel 1999, p. 21

- ↑ Morris, John Miller: Exploration from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 29, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- ↑ Chávez, Thomas E. (2004). The American book of days. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 635. ISBN 978-0-8263-2794-9.

Kleiner, Diana J.: Galveston County from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

Carmody, John M. (1945). Louisiana: a guide to the state. New York: Hastings House. p. 542. ISBN 978-1-60354-017-9. - ↑ Ladd, Kevin: El Orcoquisac from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ↑ "El Orcoquisac". Texas Beyond History. University of Texas. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ↑ "Fort Anahuac Visitors Center" (PDF). Chambers County. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Gard, Leigh: San Leon, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved December 22, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Chang (2006), p. 187

Kearney (2008), p. 177 - ↑ Warren, Harris Gaylord: Lafitte, Jean from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 7, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- 1 2 3 4 Gallaway, Alecya (July 2003). "Armand Bayou Watershed History". Armand Bayou Watershed Partnership.

The earliest information about farming in the watershed actually originated on the land of Anson Taylor who was at Taylor Lake and Taylor Bayou. Taylor was an associate of Jean Lafitte and sold his produce, firewood, and meat from wild game and cattle to Lafitte’s camp town, Campechy, on Galveston Island.

- ↑ Groneman, Bill: Taylor, James from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ↑ Warren, Harris Gaylord: The Long Expedition from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 7, 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

Henson, Margaret Swett: Perry's Point from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 7, 2010. Texas State Historical Association. - ↑ Gracy, David B. II: Moses Austin from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 7, 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Dickinson, John from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved December 18, 2009. Texas Historical Association.

Scott, William from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 4, 2010. Texas Historical Association.

Iiams, John from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 4, 2010. Texas Historical Association. - ↑ Barker, Eugene C.: Austin, Stephen Fuller from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 29, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- ↑ Armand Bayou from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved December 21, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Sage (2002), p. 27.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Margaret Bearden: Campbell's Bayou from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- ↑ Himmel 1999, p. 40

- 1 2 Reichstein, Andreas: Galveston Bay and Texas Land Company from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 15, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Barker (1969), pp. 277–278.

- ↑ Rodríguez (1997), p. 63-65.

- ↑ Sage (2002), p. 27–28.

- ↑ Henson, Margaret Swett: New Washington Association from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 15, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

Benham, Priscilla Myers: Austinia, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved December 21, 2009. Texas State Historical Association. - ↑ Henson, Margaret Swett: Anahuac Disturbances from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 14, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Barker, Eugene C.; Pohl, James W.: Texas Revolution from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 15, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Kemp, L. W.: San Jacinto, Battle of from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 15, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Austinia, TX from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 11, 2010. Texas State Historical Association

- 1 2 3 4 Pomeroy, C. David, Jr.: Allen Ranch from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- 1 2 3 Young, Buck A.: Baytown, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Benham, Priscilla Myers: Texas City, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 29, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- ↑ McComb, David C.: Houston, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 15, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

Muir, Andrew Forest: Harrisburg, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 15, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

Davenport (1843), p. 170. - 1 2 Dunn, Roy Sylvan. Dunn, Roy Sylvan: Hurricanes from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 29, 2009., Texas State History Association.

- ↑ Kleiner, Diana J.: Chambers County from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 15, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- 1 2 Rocap, Pember W.: DICKINSON, TEXAS from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- 1 2 3 4 Kleiner, Diana J.: League City, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 15, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

Kleiner, Diana J.: Webster, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

Benham, Priscilla Myers: Texas City, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association. - ↑ Johnston 1991, pp. 61–68

- 1 2 3 4 Greene, Casey Edward: Clear Lake City, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- ↑ Mitchell, Sean (June 18, 2008). "Our Settlement gets Texas Historical Marker". Galveston County Daily News.

- 1 2 3 4 Pomeroy, C. David, Jr.: Pasadena, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 29, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- ↑ Price (1896), pp. 177–178

- ↑ Kolodzy, Ron: La Porte, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 19, 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

- 1 2 Adams, Denise. "Sylvan Beach: La Porte's Swinging Shoreline". Regional Vue Point. JMMC Publishing. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

Antrobus (2005), p. 51–52. - ↑ "Weather Events: The 1900 Galveston Hurricane". The Weather Doctor. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ↑ Munsart (1997), p. 119

- ↑ "Pasadena Texas – History". Global Oneness. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

The Galveston Hurricane of 1900 caused many people to resettle in Pasadena.

- ↑ "Our City: The Birthplace of Free Texas". City of Pasadena. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

- ↑ "The Port of Texas City" (PDF). Texas City Library. Retrieved September 12, 2009.

The Texas City Improvement Company, a forerunner of Texas City Terminal and the Mainland Company, Incorporated in April 1893. ... Competition for the shipment of cotton and grain was intense because of the established ports of Houston and Galveston.

- ↑ Taylor, April (April 2007). "An Investigation of Sediment Transport Behind the Texas City Dike" (PDF). Texas A&M University.

- ↑ "Time and Events in Conservation History". Texas Legacy Project. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ↑ Sage (2002), p. 37.

- ↑ Henson (1993), p. 46.

- ↑ Henson (1993), p. 46–47.

Olien, Roger M.: Oil and Gas Industry from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association - ↑ Smith, Julia Cauble: Anahuac Field from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 9, 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Hinton (2002), p. 134

- ↑ Henson, Margaret Swett: HARRIS COUNTY from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved October 27, 2009. Texas State Historical Association

- ↑ Campbell (2009), p. 117.

- ↑ Dillingham (1911), p. 475.

- ↑ Saibara, Seito from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved January 26, 2010. Texas State Historical Association.

- 1 2 Ramos (2004), p. 154

- ↑ Kearney (2008), pp. 177–178

Fox (2007), p. 212 - ↑ Haile, Bartee (March 16, 2005). "Bootleggers Shoot It Out In Galveston" (PDF). The Lone Star Iconoclast. 6 (16): 15.

In the early 1920s, the island became 'a major point of entry' for illicit liquor. Regular as clockwork, local smugglers in high-powered speedboats rendezvoused with foreign freighters full of contraband alcohol. Hundreds if not thousands of cases a week were secretly slipped ashore for shipment to speakeasies throughout Texas and as far north as Detroit.

- ↑ McComb (1986), p. 160.

- ↑ Burka, Paul (December 1983). "Grande Dame of the Gulf". Texas Monthly: 168.

- 1 2 Jasinski, Laurie E.: Clear Lake Shores, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 4, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Stephens (1997), p. 9

- ↑ "Our City: The Birthplace of Free Texas". City of Pasadena. Retrieved September 22, 2009.

- ↑ Leatherwood, Art: Ellington Field from the Handbook of Texas Online Texas State Historical Association.

- 1 2 3 "1: Introduction". Ambient Water and Sediment Quality of Galveston Bay: Present Status and Historical Trends (PDF). Galveston: Galveston Bay National Estuary Program. 1992. p. 12.

- ↑ Henson (1993), p. 51.

Holzer, T.L.; Bluntzer, R.L. (1984). "Land subsidence near oil and gas-fields, Houston, Texas" (PDF). Ground Water. 22 (4): 450–459. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6584.1984.tb01416.x. Retrieved December 25, 2009. - ↑ Coplin, Laura S.; Galloway, Devin. "Houston-Galveston, Texas: Managing coastal subsidence" (PDF). U.S. Geological Service. p. 35. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

Christian, Carol (May 14, 2009). "Restoration project on Sylvan Beach has begun $3.5 million plan will create 2,000 feet of shoreline, protective barricade". Houston Chronicle. - ↑ Melosi (2007), p. 165.

- ↑ Melosi (2007), p. 168–170.

- ↑ Kleiner, Diana J.: Taylor Lake Village, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 7, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

Kleiner, Diana J.: Nassau Bay, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved November 8, 2009. Texas State Historical Association. - ↑ Cartwright, Gary (July 1978). "On the Waterfront". Texas Monthly: 161–162.

- ↑ "U.S. Port Ranking by Cargo Volume 2004". American Association of Port Authorities. 2004.

- ↑ Port of Houston Magazine. Port of Houston Authority. 39. 1997.

Today, Barbours Cut Terminal ranks seventh among US ports in container volume.

Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Environmental Report Cards for 10 U.S. Ports" (PDF). Harboring Pollution: The Dirty Truth about U.S. Ports. Natural Resources Defense Council: 50. March 2004.

- ↑ Melosi (2007), pp. 254–255

- ↑ "Stewardship & Education Programs". Armand Bayou Nature Center. Archived from the original on June 10, 2006. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- ↑ Kleiner, Diana J.: Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved December 22, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Roddy (2008), p. 265

Barrington (2008), p. 266

Antrobus (2005), p. 57 - ↑ "BayTran and BAHEP promote Bay Area Houston Regional Brand (Press Release)". Guidry News. November 13, 2009.

"About the Chamber". Clear Lake Area Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved December 21, 2009.

"Bay Area Houston: A Regional Brand" (PDF). Bay Area Houston Economic Partnership. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 28, 2006. Retrieved December 21, 2009. - ↑ Kleiner, Diana J.: Bacliff, Texas from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved December 22, 2009. Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Lomax, John Nova (September 11, 2008). "Gangsters in Bacliff". Houston Press.

"Index — Census 2000 Data By Super Neighborhoods". City of Houston. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

"U.S Census Bureau: American Factfinder". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2009. - ↑ Tresaugue, Matthew (August 22, 2009). "The state of the bay". Houston Chronicle.

- ↑ Casselman, Ben (June 4, 2009). "Planning the 'Ike Dike' Defense". Wall Street Journal.

References

- Antrobus, Sally (2005). Galveston Bay. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-461-8.

- Baird, David; Jarolim, Edie; Schlecht, Neil E.; Peterson, Eric (2005). Frommer's Texas. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 0-7645-7668-2.

- Barker, Eugene Campbell (1969). The Life of Stephen F. Austin, Founder of Texas, 1793–1836: A Chapter in the Westward Movement of the Anglo-American People. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-78421-5.

- Barrington, Carol (2008). Day Trips from Houston: Getaway Ideas for the Local Traveler. Guilford, CT: Global Pequot. ISBN 0-7627-3867-7.

- Blackburn, Jim (2004). The book of Texas bays. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-339-5.

- Cairns, William J.; Rogers, Patrick M. (1990). Onshore impacts of offshore oil. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-85334-974-7.

- Campbell, Howard (2009). Drug War Zone: Frontline Dispatches from the Streets of El Paso and Juárez. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72126-5.

- Chang, Yushan (2006). Newcomer's Handbook Neighborhood Guide: Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, and Austin. Portland, OR: First Books. pp. 180–192. ISBN 0-912301-70-8.

- Davenport, Bishop (1843). A history and new gazetteer: or geographical dictionary, of North America and the West Indies. New York: S W Benedict & Co.

- Dillingham, William Paul, ed. (1911). Reports of the Immigration Commission: Part 24: Recent Immigrants in Agriculture (United States Immigration Commission). 1. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Fox, Stephen; Cheek, Richard (2007). The country houses of John F. Staub. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-595-9.

- Sage, Theron; Gallaway, Alecya (2002). Lester, Jim; Gonzalez, Lisa, eds. The State of the Bay: A Characterization of the Galveston Bay Ecosystem (2 ed.). Galveston: Galveston Bay Estuary Program.

- Henson, Margaret Swett (1993). The history of Galveston Bay resource utilization. Galveston Bay National Estuary Program.

- Himmel, Kelly F. (1999). The conquest of the Karankawas and the Tonkawas, 1821-1859. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-867-3.

- Hinton, Diana Davids; Olien, Roger M. (2002). Oil in Texas: the gusher age, 1895–1945. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-76056-1.

- Kearney, Syd (2005). A Marmac Guide to Houston and Galveston. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company. ISBN 1-58980-322-1.

- Johnston, Marguerite (1991). Houston, the unknown city, 1836–1946. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0-89096-476-9.

- Munsart, Craig A. (1997). American history through earth science. Wesport, CT: Teacher Ideas Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-585-22334-3.

- Naylor, June (2006). "The Gulf Coast". Texas. Guilford, CT: Global Pequot. ISBN 1-56440-483-8.

- Newcomb, William Wilmon (1961). The Indians of Texas, from prehistoric to modern times. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-78425-2.

- Perttula, Timothy K. (2004). The Prehistory of Texas. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-194-5.

- Price, D. J. (1896). The Texarkana gateway to Texas and the Southwest. St. Louis, MO: Woodward & Tiernan.

- Ramos, Mary G.; Reavis, Dick J. (2004). Texas. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-676-90502-1.

- Roddy, Laurie (2008). 60 Hikes Within 60 Miles: Houston: Includes Huntsville, Galveston, and Beaumont. Birmingham, AL: Menasha Ridge Press. ISBN 978-0-89732-958-3.

- Rodríguez O., Jaime E.; Vincent, Kathryn (1997). Myths, Misdeeds, and Misunderstandings: The Roots of Conflict in U.S.-Mexican Relations. Wilmington, DE: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8420-2662-8.

- Stephens, Hugh W. (1997). The Texas City disaster, 1947. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-77722-1.

Further reading

- Epperson, Jean L. (1995). Historical vignettes of Galveston Bay. Woodville, TX: Dogwood Press. ISBN 978-0-9646846-8-3.

- Friendswood Development Company (1991). Clear Lake City. Friendswood Development Company.

- Sloane III; Story Jones (2009). Houston in the 1920s and 1930s. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-7149-2.

External links

- El Orcoquisac

- Akokisa Indian Village

- The Battle of San Jacinto

- The 1947 Texas City Disaster

- Anahuac History

- The Birthplace of Free Texas (City of Pasadena)

- History of Baytown

- History of Kemah

- Johnson Space Center History

Coordinates: 29°29′59″N 95°05′23″W / 29.499797°N 95.089784°W