History of equity and trusts

| Equitable doctrines |

|---|

|

| Doctrines |

| Defences |

| Equitable remedies |

| Related |

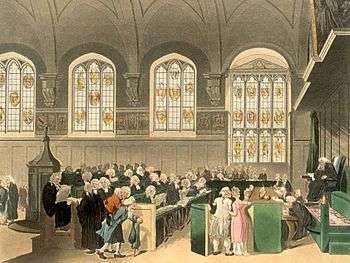

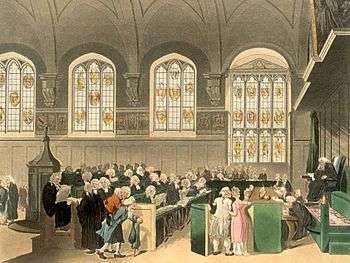

The history of equity and trusts concerns the development of the body of rules known as equity, English trust law and its spread into a modern body of trust law around Commonwealth and the United States.

The law of trusts was constructed as part of "equity", a body of principles made by the Courts of Chancery, which sought to correct the strictness of the common law. The trust was an addition to the law of property, in the situation where one person held legal title to property, but the courts decided it was fair, just or "equitable" that this person be compelled to use it for the benefit of another. This recognised a split between legal and beneficial ownership: the legal owner was referred to as a "trustee" (because he was "entrusted" with property) and the beneficial owner was the "beneficiary".

Ancestors to trust law

Possible earliest concept of equity in land held in trust is the depiction of this ancient king ( trustor ) which grants property back to its previous owner ( beneficiary ) during her absence, supported by witness testimony ( trustee ). In essence and in this case, the king, in place of the later state ( trustor and holder of assets at highest position ) issues ownership along with past proceeds ( equity ) back to the beneficiary:

On the testimony of Gehazi the servant of Elisha that the woman was the owner of these lands, the king returns all her property to her. From the fact that the king orders his eunuch to return to the woman all her property and the produce of her land from the time that she left ... [1]

- Homer, Iliad (ca 750 BC)

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics (ca 350 BC) Book V, ch 10, Equity, a corrective of legal justice.

Roman law had a well-developed concept of the trust (fideicommissum) created by wills. However, these testamentary trusts did not develop into the inter vivos (living) trusts which apply while the creator lives. This was created by later common law jurisdictions. The waqf is a similar institution in Islamic law, restricted to charitable trusts.

Middle Ages

The law of trusts first developed in the 12th century from the time of the crusades under the jurisdiction of the King of England. The "common law" regarded property as an indivisible entity, as it had been done through Roman law and the continental version of civil law. Where it seemed "inequitable" (i.e. unfair) to let someone with legal title hold onto it, the King's representative, the Lord Chancellor who established the Courts of Chancery, had the discretion to declare that the real owner "in equity" (i.e. in all fairness) was another person. When a landowner left England to fight in the Crusades, he conveyed ownership of his lands in his absence to manage the estate and pay and receive feudal dues, on the understanding that the ownership would be conveyed back on his return. However, Crusaders often encountered refusal to hand over the property upon their return. Unfortunately for the Crusader, English common law did not recognize his claim. As far as the King's courts were concerned, the land belonged to the trustee, who was under no obligation to return it. The Crusader had no legal claim. The disgruntled Crusader would then petition the king, who would refer the matter to his Lord Chancellor. The Lord Chancellor could decide a case according to his conscience. At this time, the principle of equity was born. The Lord Chancellor would consider it "unconscionable" that the legal owner could go back on his word and deny the claims of the Crusader (the "true" owner). Therefore, he would find in favour of the returning Crusader. Over time, it became known that the Lord Chancellor's court (the Court of Chancery) would continually recognize the claim of a returning Crusader. The legal owner would hold the land for the benefit of the original owner, and would be compelled to convey it back to him when requested. The Crusader was the "beneficiary" and the acquaintance the "trustee". The term "use of land" was coined, and in time developed into what we now know as a "trust".

In medieval English trust law, the settlor was known as the feoffor to uses while the trustee was known as the feoffee to uses and the beneficiary was known as the cestui que use, or cestui que trust.

Renaissance

- Charity and the British Museum

- Statute of Uses 1535

- Royal Exchange, London est 1565

- Earl of Oxford’s case (1615) 1 Ch Rep 1, (1615) 21 ER 485

- Dudley v. Dudley (1705) 24 ER 117

19th century and fusion

"Antitrust law" emerged in the 19th century when industries created monopolistic trusts by entrusting their shares to a board of trustees in exchange for shares of equal value with dividend rights; these boards could then enforce a monopoly. However, trusts were used in this case because a corporation could not own other companies' stock and thereby become a holding company without a "special act of the legislature".[2] Holding companies were used after the restriction on owning other companies' shares was lifted.

- Judicature Act 1873 s 11, ‘equity shall prevail’.

- Indian Trusts Act 1882

- Settled Land Acts 1882-1925

Modern trusts

- Federal Commerce & Navigation Co Ltd v Molena Alpha Inc, The Nanfri [1978] 1 QB 927, Lord Denning MR, ‘During that time the streams of common law and equity have flown together and combined so as to be indistinguishable the one from the other. We have no longer to ask ourselves: what would the courts of common law or the courts of equity have done before the Judicature Act? We have to ask ourselves: what should we do now so as to ensure fair dealing between the parties?’

- Welfare state and retirement

- UK company law and UK insolvency law

- Offshore tax haven and tax avoidance

- Hague Convention on the Law Applicable to Trusts and on their Recognition (1985)

- Principles of European Trust Law (1999)

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ben-Barak, Zafrira. "Meribaal and the System of Land Grants in Ancient Israel." Biblica (1981): 73-91.

- ↑ Chandler, Jr., Alfred D. (1977). The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Harvard University Press. pp. 319–20.