Homo antecessor

| Homo antecessor Temporal range: Early Pleistocene, 1.2–0.8 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. antecessor |

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo antecessor Bermúdez de Castro et al., 1997 | |

Homo antecessor is an extinct human species (or subspecies) dating from 1.2 million to 800,000 years ago, that was discovered by Eudald Carbonell, Juan Luis Arsuaga and J. M. Bermúdez de Castro.[1] "The unique mix of modern and primitive traits led the researchers to deem the fossils a new species, H. antecessor, in 1997". Regarding its great age the species must be related to Out of Africa I, the first series of hominin expansions into Eurasia, making it one of the earliest known human species in Europe.[2]

The genus name Homo is the Latin word for "human" whereas the species name antecessor is a Latin word meaning "explorer", "pioneer" or "early settler", assigned to emphasize the belief that these people belonged to the earliest migratory waves as yet known from the European continent.

Various archaeologists and anthropologists have debated how H. antecessor relates to other Homo species in Europe, with suggestions that it was an evolutionary link between H. ergaster and H. heidelbergensis. Some anthropologists suggest H. antecessor may be the last common ancestor of modern humans and Neanderthals (via Homo heidelbergensis) because H. antecessor has a combination of primitive traits typical of earlier Homo and unique features seen in neither Neanderthals or Homo sapiens. Author Richard Klein argues that it was a separate species that evolved from H. ergaster.[3]

Some scientists consider H. antecessor to be the same species as H. heidelbergensis, who inhabited Europe from 600,000 to 250,000 years ago in the Pleistocene.[4] As a complete skull has yet to be unearthed, only fourteen fragments and lower jaw bones exist, these scholars point to the fact, that "most of the known H. antecessor specimens represent children" as "most of the features tying H. antecessor to modern people were found in juveniles, whose bodies and physical features change as they grow up and go through puberty. It’s possible that H. antecessor adults didn’t really look much like H. sapiens at all".[2][5]

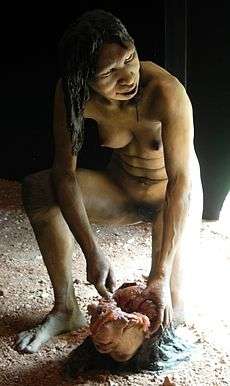

The best-preserved fossil is a maxilla that belonged to a ten-year-old individual found in Spain. Based on palaeomagnetic measurements, it is thought to be older than 857–780 ka.[6] In 1994 and 1995, 80 fossils of six individuals who may have belonged to the species were found in Atapuerca, Spain. At the site were numerous examples of cuts where the flesh had been flensed from the bones, which indicates that H. antecessor may have practiced cannibalism.[7]

Footprints presumed to be from H. antecessor dating to more than 800,000 years ago have been found at Happisburgh on the coast of Norfolk, England.[8][9][10][11]

Interpretation and phylogeny

H. antecessor's discoverers—including José Bermúdez de Castro of Spain’s National Museum of Natural Sciences, Juan Luis Arsuaga of the Universidad Complutense in Madrid and Eudald Carbonell of the University of Tarragona—suggest H. antecessor may have evolved from a population of H. erectus living in Africa more than 1.5 million years ago and then migrated to Europe, further arguing that H. antecessor gave rise to H. heidelbergensis, which then gave rise to Neanderthals, without contradicting the previous phylogenetic analysis.[12][13]

A 2013 DNA analysis from a 400,000-year-old femur from Spain's Sima de los Huesos in the Atapuerca Mountains – the oldest hominin sequence yet published – did not help to overcome contradictions. Results "left researchers baffled" as the sequence "suggests [a closer] link to [the] mystery population" of the Denisovans instead of the Neanderthals as was anticipated.[14]

According to the Science X Network the excavation team at the cave site of Gran Dolina has succeeded to provide conclusive dating of the strata where the Homo antecessor fossils were found. A 2014 publication in the Journal of Archaeological Science states that the sediment of Gran Dolina is 900,000 years old.[15]

A review of the Spanish National Research Centre for Human Evolution (CENIEH) in 2015, titled "Homo antecessor: The state of the art eighteen years later" only yields vague statements on the species' phylogenetic position: "... a speciation event could have occurred in Africa/Western Eurasia, originating a new Homo clade", and further: "Homo antecessor ... could be a side branch of this clade placed at the westernmost region of the Eurasian continent".[16]

Physiology

H. antecessor was about 1.6–1.8 m (5½–6 feet) tall, and males weighed roughly 90 kg (200 pounds). Their brain sizes were roughly 1,000–1,150 cm³, smaller than the 1,350 cm³ average of modern humans. Due to fossil scarcity, very little more is known about the physiology of H. antecessor, yet it was likely to have been more robust than H. heidelbergensis.[17]

According to Juan Luis Arsuaga, one of the co-directors of the excavation in Burgos, H. antecessor might have been right-handed, a trait that makes the species different from the other apes. This hypothesis is based on tomography techniques. Arsuaga also claims that the frequency range of audition is similar to H. sapiens, which makes him suspect that H. antecessor used a symbolic language and was able to reason.[17] Arsuaga's team is currently pursuing a DNA map of H. antecessor.

Based on teeth eruption pattern, the researchers think that H. antecessor had the same development stages as H. sapiens, though probably at a faster pace. Other significant features demonstrated by the species are a protruding occipital bun, a low forehead, and a lack of a strong chin. Some of the remains are almost indistinguishable from the fossil attributable to the 1.5 million year old Turkana Boy, belonging to H. ergaster.

Fossil sites

The only known fossils of H. antecessor were found at two sites in the Sierra de Atapuerca region of northern Spain (Gran Dolina and Sima del Elefante). The type specimen for H. antecessor is ATD 6-5, dating to approximately 780,000 years ago.[18] Other sites yielding fossil evidence of this hominid have been discovered in the United Kingdom and France.

Gran Dolina

Archaeologist Eudald Carbonell i Roura of the Universidad Rovira i Virgili in Tarragona, Spain and palaeoanthropologist Juan Luis Arsuaga Ferreras of the Complutense University of Madrid discovered Homo antecessor remains at the Gran Dolina (literally “Big Sinkhole”) site in the Sierra de Atapuerca, east of Burgos in what now is Spain. The H. antecessor remains have been found in level 6 (TD6) of the Gran Dolina site.

More than 80 bone fragments from six individuals were uncovered in 1994 and 1995. The site also had included approximately 200 stone tools and 300 animal bones. Stone tools including a stone carved knife were found along with the ancient hominin remains. All these remains were dated at least 900,000 years old.[19] The best-preserved remains are a maxilla (upper jawbone) and a frontal bone of an individual who died at the age of 10–11.

Sima del Elefante

On June 29, 2007, Spanish researchers working at the Sima del Elefante (“Pit of the Elephant”) site in the Atapuerca Mountains of Spain announced that they had recovered a molar dated to 1.2–1.1 million years ago. The molar was described as "well worn" and from an individual between 20 and 25 years of age. Additional findings announced on 27 March 2008 included a mandible fragment, stone flakes, and evidence of animal bone processing.[20]

Suffolk, England

In 2005, flint tools and teeth from the same strata as fossils of the water vole Mimomys savini, a key dating species, were found in the cliffs at Pakefield near Lowestoft in Suffolk. This suggests that hominins existed in England 700,000 years ago, potentially a cross between Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis.[21][22][23][24][25]

Norfolk, England

In 2010, stone tool finds were reported in Happisburgh, Norfolk, England,[26][27] thought to have been used by H. antecessor, suggesting that the early hominin species also lived in England about 950,000 years ago – the earliest known population of the genus Homo in Northern Europe.

In May 2013, sets of fossilized footprints were discovered in an estuary at Happisburgh.[10] They are thought to date from 800,000 years ago and are theorized to have been left by a small group of people, including several children and one adult male. The tracks are considered the oldest human footprints outside Africa and the first direct evidence of humans in this time period in the UK or northern Europe, previously known only by their stone tools.[28] Within two weeks, the tracks had been covered again by sand, but scientists made 3D photogrammetric images of the prints, and attributed them to H. antecessor.[9]

Lézignan-la-Cèbe, France

Twenty tools dating back to the Paleolithic (pebble culture, 1.6 million years ago) were found in 2008.[29]

See also

References

- BBC – Dawn of Man (2000) by Robin McKie ISBN 0-7894-6262-1

Notes

- ↑ Bermudez de Castro; Arsuaga; Carbonell; Rosas; Martinez; Mosquera (1997). "A hominid from the Lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain: possible ancestor to neandertals and modern humans". Science. 276: 1392–1395. doi:10.1126/science.276.5317.1392. PMID 9162001.

- 1 2 "Homo antecessor: Common Ancestor of Humans and Neanderthals?". Smithsonian. November 26, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ Klein, Richard. 2009. "Hominin Disperals in the Old World" in The Human Past, ed. Chris Scarre, 2nd ed., p. 108.

- ↑ "Homo antecessor". Australian Museum. November 26, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ "The Last Human: A Guide to Twenty-two Species of Extinct Humans By Esteban E. Sarmiento, Gary J. Sawyer, Richard Milner, Viktor Deak, Ian Tattersall". Google Books. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ Falguères, Christophe; Bahain, J.; Yokoyama, Y.; Arsuaga, J.; Bermudez de Castro, J.; Carbonell, E.; Bischoff, J.; Dolo, J. (1999). "Earliest humans in Europe: the age of TD6 Gran Dolina, Atapuerca, Spain". Journal of Human Evolution. 37 (3-4): 343–352 [351]. doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0326.

- ↑ Fernández-Jalvo, Y.; Díez, J. C.; Cáceres, I.; Rosell, J. (September 1999). "Human cannibalism in the Early Pleistocene of Europe (Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain)". Journal of Human Evolution. Academic Press. 37 (34): 591–622. doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0324. PMID 10497001.

- ↑ Lawless, Jill (7 February 2014). "Scientists find 800,000-year-old footprints in UK". AP News. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- 1 2 Ghosh, Pallab (7 February 2014). "Earliest footprints outside Africa discovered in Norfolk". BBC. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- 1 2 Ashton, N; Lewis, SG; De Groote, I; Duffy, SM; Bates, M; et al. (2014). "Hominin Footprints from Early Pleistocene Deposits at Happisburgh, UK". PLoS ONE. 9 (2): e88329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088329. PMC 3917592

. PMID 24516637.

. PMID 24516637. - ↑ Ashton, Nicholas (7 February 2014). "The earliest human footprints outside Africa". British Museum. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ↑ "Homo antecessor: Common Ancestor of Humans and Neanderthals? By Erin Wayman H. antessor's discoverers—including José Bermúdez de Castro...". smithsonian.com. November 26, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ Carretero, JM; Lorenzo, C; Arsuaga, JL (October 1, 1999). "Axial and appendicular skeleton of Homo antecessor". J. Hum. Evol. 37: 459–99. doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0342. PMID 10496997.

- ↑ "Hominin DNA baffles experts Analysis of oldest sequence from a human ancestor suggests link to mystery population.". Nature Publishing Group. December 4, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Dating is refined for the Atapuerca site where Homo antecessor appeared". Science X Network. February 7, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ↑ "Homo antecessor: The state of the art eighteen years later". Quaternary International. Science Direct. May 23, 2015. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.03.049. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- 1 2 El Mundo newspaper (in Spanish)

- ↑ "Homo antecessor". eFossils. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- ↑ Parés, J.M. (July 24, 2013). "Reassessing the age of Atapuerca-TD6 (Spain): New paleomagnetic results by L. Arnolda, M. Duvala, M. Demuroa, A. Pérez-Gonzáleza, J.M. Bermúdez de Castro, E. Carbonell, J.L. Arsuaga". Journal of Archaeological Science. 40: 4586–4595. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ↑ Carbonell, Eudald (2008-03-27). "The first hominin of Europe". Nature. 452 (7186): 465–469. doi:10.1038/nature06815. PMID 18368116. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- ↑ Parfitt.S et al (2005) 'The earliest record of human activity in northern Europe', Nature 438 pp.1008-1012, 2005-12-15. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- ↑ Roebroeks.W (2005) 'Archaeology: Life on the Costa del Cromer', Nature 438 pp.921-922, 2005-12-15. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- ↑ Parfitt.S et al (2006) '700,000 years old: found in Pakefield', British Archaeology, January/February 2006. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

- ↑ Good. C & Plouviez. J (2007) The Archaeology of the Suffolk Coast Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service [online]. Retrieved 2009-11-28.

- ↑ Tools unlock secrets of early man, BBC news website, 2005-12-14. Retrieved 2011-04-15.

- ↑ Moore, Matthew (8 July 2010). "Norfolk earliest known settlement in northern Europe". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Ghosh, Pallab (7 July 2010). "Humans' early arrival in Britain". BBC. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Ancient stone tools found in Norfolk to feature in exhibition, BBC Norfolk website, 2014-01-13. Retrieved 2014-02-07.

- ↑ Jones, Tim. "Lithic Assemblage Dated to 1.57 Million Years Found at Lézignan-la-Cébe, Southern France «". Anthropology.net. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homo antecessor. |

- Homo antecessor

- Homo antecessor in northern Europe

- Early Human Phylogeny

- Spanish National Research Centre for Human Evolution (CENIEH)

- Atapuerca

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).