Homo gautengensis

| Homo gautengensis Temporal range: Pleistocene, 1.9–0.6 Ma | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Subtribe: | Hominina |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | H. gautengensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Homo gautengensis Curnoe, 2010 | |

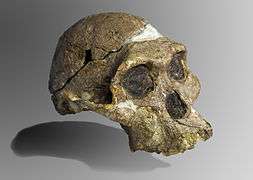

Homo gautengensis is a hominin species proposed by biological anthropologist Darren Curnoe in 2010. The species is composed of South African hominin fossils previously attributed to Homo habilis, Homo ergaster, or in some cases Australopithecus and is argued by Curnoe to be the earliest species in the genus Homo.[1]

Discovery and analysis

Analysis announced in May 2010 of a partial skull found decades earlier in South Africa's Sterkfontein Caves in Gauteng near Johannesburg identified the species, named Homo gautengensis by anthropologist Dr. Darren Curnoe of the UNSW School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences. The species has been considered by Lee Berger and co-workers to be an invalid taxon because it conflicts with their interpretations of Australopithecus sediba. The species' first remains were discovered in the 1930s by Broom and Robinson, and the most complete skull (species Holotype Stw 53) was recovered in 1977 and was argued to belong to the species Homo habilis.[2] The type specimen has been discussed in some refereed publications as being synonymous with A. africanus, but most analyses have considered it to belong in the genus Homo, and several have suggested it sampled a novel species prior to Curnoe's description.

Geochronology

Identification of H. gautengensis was based on partial skulls, several jaws, teeth and other bones found at various times and cave sites in the Cradle of Humankind. The oldest specimens are those from Swartkrans Member 1 (Hanging Remnant) between 1.9 and 1.8 Ma .[3] The type specimen StW 53 from Sterkfontein is dated to sometime between 1.8 and 1.5 Ma.[4] A specimen from Gondolin Cave is dated to ~1.8 Ma.[5][6] Other specimens from Sterkfontein Member 5 date to between 1.4 and 1.1 Ma, with the youngest specimens from Swartkrans Member 3 dated to sometime between 1.0 and 0.6 Ma.[7]

Description

According to Curnoe, Homo gautengensis had big teeth suitable for chewing plant material.[8] It was "small-brained" and "large-toothed," and was "probably an ecological specialist, consuming more vegetable matter than Homo erectus, Homo sapiens, and probably even Homo habilis." It apparently produced and used stone tools and may even have made fire, as there is evidence for burnt animal bones associated with H. gautengensis' remains.

Curnoe believes H. gautengensis stood just over 3 feet (0.91 m) tall and weighed about 110 pounds (50 kg). According to Curnoe, it walked on two feet when on the ground, "but probably spent considerable time in trees, perhaps feeding, sleeping and escaping predators."

The researchers believe it lacked speech and language skills. Due to its anatomy and geological age, researchers think that it was a close relative of Homo sapiens but not necessarily a direct ancestor.

Implications

Earlier in 2010, the discovery of a new fossil primate species Australopithecus sediba was announced. A. sediba seems "much more primitive than H. gautengensis, and lived at the same time and in the same place," according to Curnoe, and as a result, "Homo gautengensis makes Australopithecus sediba look even less likely to be the ancestor of humans.

One reason for the sudden increase in the discovery of Homo species is improved analysis methods, often based on prior finds, DNA work, and a better understanding of where such remains might exist.[8]

Curnoe instead proposes that Australopithecus garhi, found in Ethiopia and dating to about 2.5 million years ago, is a better explanation for the earliest non-Homo direct ancestor in the human evolutionary line.

Bones even older than those of Homo gautengensis await study and classification. According to Colin Groves, a professor in the School of Archaeology and Anthropology at the Australian National University in Canberra, "Here were a number of distinctive, perhaps short-lived, species of proto-humans living in both eastern and southern Africa in the period between 2 and 1 million years ago."[8]

See also

- Australopithecus sediba, a contemporary stem-human species, also identified in 2010

- Paranthropus - a parallelly evolved genus.

References

- ↑ Curnoe, D. 2010, "A review of early Homo in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the description of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. nov.)." HOMO - Journal of Comparative Human Biology, vol.61 pp.151–177.

- ↑ "Reappraisal of the taxonomic status of the cranium StW 53 from the Plio/Pleistocene of Sterkfontein, in South Africa"

- ↑ Pickering et al. 2011, "Contemporary flowstone development links early hominin bearing cave deposits in South Africa" Earth and Planetary Science Letters 306 (1-2) , pp. 23-32.

- ↑ Herries & Shaw. 2011, "Palaeomagnetic analysis of the Sterkfontein palaeocave deposits: Implications for the age of the hominin fossils and stone tool industries" Journal of Human Evolution 60 (5) , pp. 523-539

- ↑ Adams et al., 2007. "Taphonomy of a South African cave: geological and hydrological influences on the GD 1 fossil assemblage at Gondolin, a Plio-Pleistocene paleocave system in the Northwest Province, South Africa" Quaternary Science Reviews 26 (19-21) , pp. 2526-2543

- ↑ Herries et al., 2006. "Speleology and magnetobiostratigraphic chronology of the GD 2 locality of the Gondolin hominin-bearing paleocave deposits, North West Province, South Africa" Journal of Human Evolution 51 (6) , pp. 617-631

- ↑ Herries et al., 2009. "A multi-disciplinary seriation of early Homo and Paranthropus bearing palaeocaves in southern Africa" Quaternary International 202 (1-2) , pp. 14-28

- 1 2 3 "Get Ready for More Proto-Humans"

External links

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).