Hunsrück

| Hunsrück | |

|---|---|

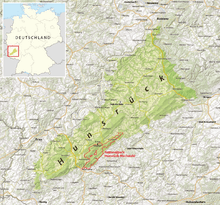

Location of the Hunsrück in Germany | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Erbeskopf |

| Elevation | 816.32 m (2,678.2 ft) |

| Coordinates | Coordinates: 50°00′N 7°30′E / 50.000°N 7.500°E |

| Geography | |

| Country | Germany |

| State/Province | Rhineland-Palatinate |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Central Uplands |

The Hunsrück (German pronunciation: [ˈhʊnsʁʏk]) is a low mountain range in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is bounded by the river valleys of the Moselle (north), the Nahe (south), and the Rhine (east). The Hunsrück is continued by the Taunus mountains on the eastern side of the Rhine. In the north behind the Moselle it is continued by the Eifel. To the south of the Nahe is the Palatinate region.

Many of the hills are no higher than 400 metres above sea level. There are several chains of much higher peaks within the Hunsrück, all bearing names of their own: the (Black Forest) Hochwald, the Idar Forest, the Soonwald, and the Bingen Forest. The highest mountain is the Erbeskopf (816 m).

Notable towns located within the Hunsrück include Simmern, Kirchberg, and Idar-Oberstein, Kastellaun, and Morbach. Frankfurt-Hahn Airport, a growing low-fare carrier and cargo airport is also located within the region.

The climate in the Hunsrück is characterised by rainy weather, and mist rising in the morning. Slate is still mined in the mountains. Since 2010, the region has become one of Germany's major onshore wind power regions, with major wind farms located near Ellern and Kirchberg. Nature-based tourism has increased in recent years and in 2015, a new national park was inaugurated. Culturally, the region is best known for its Hunsrückisch dialect and through depictions in the Heimat film series. The region experienced significant emigration in the mid-19th century, particularly to Brazil.

Geography

Location

The heart of the Hunsrück is formed by the Hunsrück Plateau and the Simmern Bowl. In the northwest the Hunsrück is bounded by the Moselle river and in the east by the Rhine. Its northeasternmost tip is thus formed by the Deutsches Eck. The Nahe - on the edge of the Bingen Forest, the Soonwald and the Lützelsoon - borders the mountains to the south. The Lower Naheland is not part of the Hunsrück, but belongs to the Upper Rhine Plain. The Idar Forest, the Hochwald and the Wildenburger Kopf adjoin the Hunsrück to the southwest. Here the Upper Nahe Hills rise in the shadow of the Hunsrück. The Osburger Hochwald, Schwarzwalder Hochwald and the rivers Saar and Ruwer form the western perimeter. Its southern continuation is formed by the Westrich and the North Palatine Uplands.

The low mountain range is around 100 km long (SW to NE) and an average of 25 to 30 km wide (NW to SE). Its perimeter is a heavily incised peneplain with elongated ridges in the south (the Hochwald, Idar Forest, Soonwald and Bingen Forest).[1] The range, which begins at the Saar in the southwest and, with breaks, reaches as far as the Rhine, climbs to its highest point in the Hochwald at the Erbeskopf (816.32 m), the highest peak in the Hunsrück and in the Rhenish Massif west of the Rhine. It continues to the NE as the Idar Forest with its highest peaks, An den zwei Steinen (766.2 m) and the Idarkopf (745.7 m). Its northeasternmost part is formed by the Soonwald (highest mountain: the Ellerspring, 656.8 m), the Lützelsoon (Womrather Höhe, 599.1 m) and the Bingen Forest (Kandrich, 638.6 m). All these ranges form an almost unbroken belt of forest.[2] – To the east of the Rhine the crest of the Hunsrück is continued by the Taunus.

Geomorphologically the Hunsrück bears great similarities to the Eifel, the Taunus and the Westerwald, which are also part of the Rhenish Massif.

The Hunsrück hill road runs from west to east from Saarburg to Koblenz. A Roman military road, the so-called Via Ausonius also once ran through the mountains in an east-west direction and linked Trier with Bingen.

In many primary schools in the Hunsrück children are taught the boundaries of the Hunsrück using the following rhyme: "Mosel, Nahe, Saar und Rhein schließen unsern Hunsrück ein." ("Moselle, Nahe, Saar and Rhine enclose our Hunsrück")

Mountains and hills

The following table lists the highest mountains and hills of the Hunsrück by sub-range (Osburger and Schwarzwalder Hochwald, Idar Forest, Haardt Forest, Soonwald, Bingen Forest and Lützelsoon) and height in metres above sea level (NN):

→

| Name | Height (metres) | Location (Natural region) | County | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erbeskopf | 816.32 | Schwarzwälder Hochwald | Bernkastel-Wittlich | Highest mountain in the Hunsrück, viewing tower |

| An den zwei Steinen | 766.2 | Idar Forest | Bernkastel-Wittlich, Birkenfeld | |

| Rösterkopf | 708.1 | Osburger Hochwald | Trier-Saaburg | Rösterkopf transmission tower |

| Haardtkopf | 658.0 | Haardt Forest | Bernkastel-Wittlich | Haardtkopf Transmitter |

| Ellerspring | 657.5 | Soonwald | Bad Kreuznach | Ellerspring Transmission Tower |

| Kandrich | 638.6 | Bingen Forest | Bad Kreuznach | Transmitter |

| Womrather Höhe | 599.1 | Lützelsoon | Bad Kreuznach, Rhein-Hunsrück | |

Flora and fauna

Despite, in places, intensive agricultural or timber use, the Hunsrück remains a landscape with a biodiversity, because many elements of the landscape can only be extensively utilised or even not used at all.

Flora

The plant world of the Hunsrück is rich and varied. In the Soonwald there are over 850 species of ferns and flowers. The traditional forest monocultures are increasingly giving way, especially as a result of windthrow damage, to mixed woods, supporting a greater variety of plant species.

Fauna

Although the Hunsrück is not classified as a bird reserve, it is home to a wide variety of bird species: woodpeckers, birds of prey and song birds may be seen at all times of the year. Even the rare and shy black stork nests in the forests. The Hunsrück is rich in mammals; red deer, roe deer and wild boar are intensively hunted. Larger predators include a few examples of wild cat or even the lynx. Red fox, badgers and pine martens are more commonly encountered.

The best known mammal in the Hunsrück has become the barbastelle. It achieved notoriety when the presence of this rare species of bat delayed construction on the runway extension at Hahn Airport.[3]

In the numerous wet areas, amphibians, like the fire salamander, and insects have found ideal habitats. Meanwhile, in areas covered by dry grassland or scree, numerous reptiles like the slow worm and smooth snake have found a home. The viper does not occur in the Hunsrück.

History

Prehistory

Finds such as stone axes indicate that the Hunsrück has been settled since the New Stone Age. Older discoveries, which prove that the area was either settled or crossed during the Old Stone Age, are rare. Middle Palaeolithic (ca. 200,000–400,000 B.C.) surface finds from Weiler bei Bingen are an exception. By contrast the Gravettian (ca. 30,000–20,000 B.C.) sites in Heddesheim (in the municipality of Guldental) and Brey (in the municipality of Rhens) are the first settlements in the area around the Hunsrück. The rather more recent Old Stone Age site of Nußbaum[4] near Bad Sobernheim and the encampment of Late Palaeolithic deer hunters in Boppard,[5] which was first discovered in 2001 by the ARRATA Archaeology Society, should also be mentioned. In 2014, Late Palaeolithich rock carvings, like those known in southern France and Spain, were found for the first time in Germany in the Hunsrück. They were portraits of animals, especially horses, about 25,000 years old carved into a 1.2 m² slab of slate.[6]

The oldest witnesses from the New Stone Age are dated to no later than the Middle Neolithic, relics of the so-called Rössen culture (whose sites include Biebernheim and Reckershausen). The majority of finds, especially of stone axes date, however, to the Late Neolithic and belong to the Michelsberg culture. Up to 2007, numerous oval stone axes were discovered, especially in the Fore-Hunsrück (Morshausen, Beulich and Macken). Likewise, finds of flint arrowheads point to a Late Neolithic (inter alia at Bell) and very Late Neolithic (Hirzenach) settlement.[7] Other finds from the Bronze Age prove that there was continual settlement (especially documented by graves and grave goods). A greater process of settlement took place in the Early Iron Age (Hallstatt period) with the Laufeld culture and in the La Tène period (5th– 1st century B.C.) with the Hunsrück-Eifel culture, which can be linked with the Celts. This is indicated, e.g. by the coach grave of Bell, the Waldalgesheim prince's grave, the circular rampart of Otzenhausen, the Pfalzfeld flame column, the upland settlement of Altburg in the Hahnenbach valley and the numerous fields of tumuli. At that time, the Hunsrück was the tribal area of the Treveri.

Roman period

Between about 50 B. C. and 400 A. D. the Romans opened up the Hunsrück by building a dense network of roads. The best known relic of this is the Via Ausonius. Numerous finds of Roman farms (Villa Rustica), settlements, like the vicus, Belginum, and military structures point to an almost total settlement of the region by the Romans.

Frankish period

The final years of the 4th century saw the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire. The Franks conquered the Roman territories and began to divide them up. This was the start of the great western and central European empire of Francia. In the mid-8th century this was divided into gaus under Carolingian rule. The northern part of the present Hunsrück foreland belonged to the Trechirgau, the southern part to the Nahegau. The Trechirgau was managed by the so-called Bertholds, the Nahegau by the Emichones. The capital of the Trechirgau, Trigorium, was in Treis. [8]

Middle Ages to French period

The Hundesrucha is mentioned for the first time in a 1074 deed from Ravengiersburg Abbey.[9]

In the Middle Ages, the Hunsrück was territorially fragmented between the counts Palatine of the Rhine, the archbishops of Trier, the counts of Sponheim and the successors of the Emichones (the Wildgraves, the Raugraves and the counts of Veldenz). There were also a number of smaller dominions.

In 1410 the Principality of Simmern emerged as a territory ruled by a side line of the counts Palatine. In the following years, Simmern became the most important residence of a noble family in the Hunsrück. Under Duke John II the town achieved supra-regional importance for a short time.

After the Thirty Years' War, Louis XIV of France made reunification demands on several principalities in the Palatinate, the Hunsrück and the Eifel. He had his troops invade and thus precipitated the Nine Years' War. In 1689 Kirchberg, Kastellaun, Simmern and the town and castle of Stromberg were set on fire. Then came the chaos of war, which led to the War of the Spanish Succession and which ended in 1713.

In the following years, trade and commerce grew. In the Hunsrück the first industry was set up by the families of Hauzeur, Pastert and Stumm. They ran mining, processing and ore smelting businesses. These, in turn, spurred the manufacture of implements for the house, farming and handicrafts: ovens, pans, boilers, weights, spades, nails, hammers, anvils, looms, spinning wheels and ammunition (cannonballs and shells weighing from 2 to 30 pounds). Leaders in the iron processing industry were the family of Stumm. Their progenitor, Christian Stumm, was a blacksmith in Rhaunensulzbach. Two of his sons were important entrepreneurs. Johann Nikolaus Stumm (1668-1743) was a smeltery owner and his sons, Johann Ferdinand, Friedrich Philipp and Christian Philipp Stumm, bought on 22 March 1806, the Neunkirchen ironworks, part of today's Saarstahl AG. Johann Michael Stumm (1683-1747) was the founder of a organ building workshop.

The notorious robbers, Johannes Bückler (known as Schinderhannes) and Johann Peter Petri (Black Peter) brought insecurity to the Hunsrück in the late 18th century.

In 1792, as a result of the French Revolution and the seizure of power by Napoleon, French troops once again invaded the territories west of the Rhine and annexed them during the French period. After the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815, most of the Hunsrück was reallocated at the Congress of Vienna to Prussia's Rhine Province. Parts of today's Birkenfeld and the northern Saarland belonged to the Oldenburg Principality of Birkenfeld until 1937.

Prussia era and emigration

The economic situation in the Hunsrück became serious during the years 1815-1845. A poor harvest in 1815 was followed by the year without a summer in 1816; grain prices rose rapidly and 1817 became a year of famine.

In September 1822, the Brazilian government sent Georg Anton Schäffer to Germany to recruit mercenaries and colonists. He arrived in 1823, as a representative of Emperor Dom Pedro I of Brazil, and visited the Hanseatic cities, Frankfurt and many of the German courts.[10] This mission sparked the first major wave of German emigrants to Brazil. Many of them were recruited by Schäffer from the Hunsrück, the northern and western parts of present-day Saarland and the Western Palatinate.

The first immigrants from the Hunsrück settled in 1824 in what is now the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, near the city of São Leopoldo. Not until 1830, did the number of emigrants to Brazil begin to fall.[11]

The 1840s in Europe were marked by inflation, crop failures and a degree of social unrest, so that again (especially in 1846 and 1861) many Hunsrück folk decided to leave in two more waves of emigration, especially to North America and Brazil.[12]

In August 1846, it was announced in Dunkirk, that free passage to Brazil would no longer be possible. At this time there over 800 people were waiting there. Prussia refused any responsibility for the impoverished and helpless emigrants. They were transported from France in three warships to Algeria and settled in the villages of Stidia and Sainte-Léonie.[13] Most of their descendants returned to France after the Algerian War in 1962.[14]

As a result of the increasing neglect and deprivation of parts of the population in Germany during the era of industrialization, an Inner Mission association was founded at the initiative of the Simmern pastor, and later superintendent, Julius Reuss, in Simmern, with the aim of building a rescue centre in the Hunsrück for children living in poverty. In 1851, an area between Simmern and Nannhausen, the Schmiedel was acquired. There, the first building was erected as a "mother house" (Mutterhaus or domus materna), which was opened on 13 September 1851 for a householder and twelve boys. Even today, the head offices of the Schmiedel organisation remain on the site.

German Reich

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1871 and the foundation of the German Reich under Prussia's leadership, the so-called Gründerzeit began. Its success did not impact the Hunsrück until later, which is why many job seekers and even entire families went looking for work in the Ruhr area and migrated there.

The Protestant pastor, later Prussian Landtag MP, Richard Oertel, founder of the Hunsrück Farmers' Union in 1892, and Albert Hackenberg, acting pastor in Hottenbach from 1879 to 1912, successfully worked to improve the economic, social and technological conditions in the Hunsrück region. They achieved this through the creation of dairy cooperatives, postal agencies and, in particular, through adult education.

First and Second World War

The First World War, the Occupation Period and inflation also had a serious impact on the economy of the Hunsrück and its inhabitants, but there were not the political tensions that arose in many places in the German Reich.

A pioneer of industrialisation in the Hunsrück was entrepreneur, Michael Felke. In 1919 he founded the Felke Möbelwerke, a company that produced and sold furniture in Central Europe until the late 1990s. It was one of the first major employer in the region.

In 1938 and 1939, the German army became interested in the Hunsrück region as a strategic deployment route to the German-French border and the Siegfried Line, building the Hunsrück Highway, 140 kilometres long, in just 100 days. Supply depots and airfields were built in the woods on both sides of the road. In the Second World War and post-war period, two places in the Hunsrück rose to notoriety: Hinzert concentration camp and Bretzenheim POW camp, the so-called "Field of Misery".

Cold War to the present

In 1946, most of the Hunsrück became part of the new state of Rhineland-Palatinate, with small elements around Nonnweiler going to the Saarland.

During the Cold War until the early 1990s, the Hunsrück was home to numerous military airfields, ammunition dumps, command positions and missile sites. The most famous were Hahn Air Base, Pferdsfeld Air Base, the Börfink Command Bunker and the Pydna Missile Base.

In 1986/87, as a result of the NATO Double-Track Decision, 96 cruise missiles, fitted with nuclear warheads, were to be stored at Pydna. On 11 Oct 1986, on the market place in Bell, what was probably the largest demonstration in the Hunsrück's history took place. Around 200,000 people, 95% of whom were not from the Hunsrück, peacefully protested against the deployment of the missiles. At the end of the day the "Hunsrück Declaration" was read out which called for a reversal of the security policy. This did not happen, however, the Cold War ended two years later anyway, and the missile based was closed on 31 August 1993, the land being acquired by the Kastellaun garrison authority.

Likewise the US airbase at Hahn was transferred in 1993 to the German authorities and became a civilian facility, Frankfurt-Hahn Airport. The airport has expanded steadily since that time.

In the early 1980s, film director, Edgar Reitz, shot the first part of his trilogy Heimat in the Hunsrück, a large part of it in Woppenroth alias Schabbach. From Apr–Aug 2012, Reitz chose the Hunsrück village of Gehlweiler for the shooting of his film Die andere Heimat - Chronik einer Sehnsucht. The film focuses on the pre-March era in the mid-19th century and the wave of emigration from the Hunsrück to Brazil.

Sights and attractions

- Baybach valley and Waldeck Castle

- Birkenfeld: museum of the local history society; Birkenfeld Castle was the residenz of the Wittelsbach line of Palatinate-Birkenfeld; residenz schloss of the grand dukes of Oldenburg

- Bundenbach: Herrenberg roofing slate pit, Celtic settlement

- Dhaun Castle: medieval knights's castle

- Dickenschied: where the martyr, Paul Schneider, worked and is buried

- Dill: ruins of one of the Sponheim family castles; church with ceiling murals by Johann Georg Engisch

- Emmelshausen: Ehrbach Gorge, Baybach valley, Hunsrück Railway

- Erbeskopf (part of Deuselbach): Hunsrückhaus Museum, highest mountain in the Hunsrück

- Feilbingert: Schmittenstollen show mine

- Fischbach (Nahe): Historic copper mine (open to visitors)

- Gemünden: Gemünden Castle, Koppenstein Castle

- Hattgenstein: observation tower

- Hermeskeil: steam engine museum, Firefighting Museum and aviation museum

- Herrstein: historic town centre

- Hinzert: memorial to the victims of Nazism at Hinzert concentration camp

- Idar-Oberstein: German Gemstone Museum, Rock church, Gemstone show mine and much more.

- Kastellaun: castle ruins and old US nuclear missile base of Pydna

- Kempfeld: Wildenburg Castle and wildlife park on the Wildenburger Kopf

- Kirchberg: market place, St. Michael's Market (Thursday after St. Michael's Day)

- Krummenau: refuge of the famous Schinderhannes

- Leisel: Heiligenbösch church and Roman baths

- Morbach: telephone museum, Hinzerath: Baldenau Castle, Wederath: Belginum archaeological park, Weiperath: timber museum and Hunolstein: Hunolstein Castle

- Neuerkirch: Cultural History Museum, agricultural implements and machines, old handicraft skills, their products and village life and culture of bygone times

- Otzenhausen: Hunnenring, a Celtic fortification

- Pfalzfeld: Flammensäule

- Ravengiersburg: "Hunsrück Cathedral" from the 12th/13th century

- Rhaunen: Protestant church with the oldest surviving Stumm organ dating to 1723, village with historic buildings from various style periods

- Sargenroth: the Nunkirche with fresco in the tower, Nunkircher Market (early September)

- Schneppenbach: Schmidtburg, extensive castle ruins above the Hahnenbach stream

- Schwollen: Sauerbrunnen (fountain)

- Seesbach: Gateway to the Soonwald, Semendis Chapel (murals by Bishop Willigis) Rock formation in the centre of the village dating to the last ice age, RC parish church, Schinderhannes' Cave

- Siesbach: Roman gravesite

- Simmern: Schinderhannes Tower, local history museum in Simmern Castle, Hunsrück Museum, Simmern

- Spabrücken: RC church with the "Black Mother of God of the Soon" (Schwarzer Mutter Gottes vom Soon), active monastery, Gräfenbacher Hütte with remains of a free-standing furnace for Soonwald ore

- Stipshausen: "Hunsrück Baroque" church and Stumm organ

- Stromberg: Stromburg Castle, home of the deutschen Michel

- Sulzbach: home of the Stumm organ-building family with a large Stumm organ, the last one made by Johann Michael Stumm

- Trollbach valley: rock landscape between Rümmelsheim Castle Layen and Münster-Sarmsheim along the Trollbach

- Woppenroth: the village which was one of the main locations for the films Heimat and Heimat 3 by Edgar Reitz. From Woppenroth one can reach the Hahnenbach valley and the Hellkirch

- Züsch: Züscher Hammer Mill, a former hammer mill once driven by water power

In popular culture

The German television drama series Heimat, directed by Edgar Reitz, examined the 20th-century life of a small fictional village in the Hunsrück.

The electronic music festival Nature One is held at the Pydna missile base in Kastellaun.

Gallery

-

A typical view of the Hunsrück countryside

-

Balduinseck ruins between Mastershausen and Buch

References

- ↑ Lexikon-Institut Bertelsmann: Das moderne Lexikon in zwanzig Bänden, Vol. 8 (1972)

- ↑ "Hunsrück" article; in: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon, Vol. 9. Leipzig, 1907.

- ↑ Airport: Mopsfledermäuse machen Ärger; Focus Online, 2 June 2005; retrieved 19 May 2014

- ↑ Wolfgang Welker: Die Eiszeitjäger von Armsheim (Rheinhessen) und Nußbaum (Nahetal); in: Schriften des Arbeitskreises Landes- und Volkskunde, Band 6; Koblenz, 2007; ISSN 1610-8132; pp. 1–13

- ↑ Wolfgang Welker: Archäologische Fundmeldungen von ARRATA e. V. – Die Entdeckung des spätpaläolithischen Fundplatzes Boppard/Rhein; in: Abenteuer Archäologie, Issue 4, 2002; ISSN 1615-7125; pp. 49–51

- ↑ Erste altsteinzeitliche Felskunst in Deutschland, Mitteilung des Ministeriums für Bildung, Wissenschaft, Weiterbildung und Kultur des Landes Rheinland-Pfalz.

- ↑ Wolfgang Welker: Archäologische Fundmeldungen von ARRATA e. V. – Eine geflügelte Pfeilspitze; in: Abenteuer Archäologie, Issue 3, 2001; ISSN 1615-7125; p. 64

- ↑ c.f. Josef Heinzelmann: Der Weg nach Trigorium …; in: Jahrbuch für westdeutsche Landesgeschichte 21 (1994), pp. 91–132

- ↑ Heinrich Beyer (1860), Urkundenbuch zur Geschichte der jetzt die Preussischen Regierungsbezirke Coblenz und Trier bildenden Mittelrheinischen Territorien (in German), Vol. 1: Von den ältesten Zeiten bis zum Jahre 1169, Koblenz, pp. 431

- ↑ Frank Westenfelder: Für Dom Pedro. Export aus Europas Armenhäusern und Gefängnissen; articles at kriegsreisende.de retrieved 22 February 2014

- ↑ Paul Roland: Ziele der Auswanderung - Brasilien; article on the website of the Emigrant Museum of Oberalben; retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ Roland Paul: Die zweite und dritte Einwanderungswelle; article on the website of the Emigrant Museum of Oberalben; retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ Björn Effgen: html Petrópolis - Ein Brasilianisches "Versailles"; article on the website of the Emigrant Museum of Oberalben; retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ Algerian emigration in regional history at www.auswanderung-rlp.de.