Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948, sometimes known as the First Kashmir War, was fought between India and Pakistan over the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu from 1947 to 1948. It was the first of four Indo-Pakistan Wars fought between the two newly independent nations. Pakistan precipitated the war a few weeks after independence by launching tribal lashkar (militia) from Waziristan,[16] in an effort to secure Kashmir, the future of which hung in the balance. The inconclusive result of the war still affects the geopolitics of both countries.

The Maharaja faced an uprising by his Muslim subjects in Poonch, fuelled by the massacres of Muslims in Jammu, and the Maharajah lost control of the western districts of his kingdom. On 22 October 1947, Muslim tribal militias crossed the border of the state,[17] claiming that they were needed to suppress a rebellion in the southeast of the kingdom.[18] These local tribal militias and irregular Pakistani forces moved to take Srinagar, but on reaching Uri they encountered resistance. Hari Singh made a plea to India for assistance, and help was offered, but it was subject to his signing an Instrument of Accession to India.[18] British officers in the sub-continent also took part in stopping the Pakistani Army from advancing.[18]

The war was initially fought by the J&K State Forces led by Major-General Scott[19] and by tribal militias from the North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas.[20] Facing the assault and a Muslim revolution in the western borders of the state,[20][21] the ruler of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu, who was a Hindu, signed an Instrument of Accession to the Union of India. The Indian and Pakistani armies entered the war after this.[20] The fronts solidified gradually along what came to be known as the Line of Control. A formal cease-fire was declared at 23:59 on the night of 1 January 1949.[22]:379 The result of the war was inconclusive, however, most neutral assessments, agree that India was the victor of the war as it was able to successfully defend[23] about two-third of the Kashmir including Kashmir valley, Jammu and Ladakh.[24][25][26][27]

Background

Prior to 1815, the area now known as "Jammu and Kashmir" comprised 22 small independent states (16 Hindu and six Muslim) carved out of territories controlled by the Amir (King) of Afghanistan, combined with those of local small rulers. These were collectively referred to as the "Punjab Hill States". These small states, ruled by Rajput kings, were variously independent, vassals of the Mughal Empire since the time of Emperor Akbar or sometimes controlled from Kangra state in the Himachal area. Following the decline of the Mughals, turbulence in Kangra and invasions of Gorkhas, the hill states fell successively under the control of the Sikhs under Ranjit Singh.[28]:536

The First Anglo-Sikh War (1845–46) was fought between the Sikh Empire, which asserted sovereignty over Kashmir, and the East India Company. In the Treaty of Lahore of 1846, the Sikhs were made to surrender the valuable region (the Jullundur Doab) between the Beas River and the Sutlej River and required to pay an indemnity of 1.2 million rupees. Because they could not readily raise this sum, the East India Company allowed the Dogra ruler Gulab Singh to acquire Kashmir from the Sikh kingdom in exchange for making a payment of 750,000 rupees to the Company. Gulab Singh became the first Maharaja of the newly formed princely state of Jammu and Kashmir,[29] founding a dynasty, that was to rule the state, the second-largest principality during the British Raj, until India gained its independence in 1947.

Partition of India

The years 1946–1947 saw the rise of All-India Muslim League and Muslim nationalism, demanding a separate State for India's Muslims. The demand took a violent turn on the Direct Action Day (16 August 1946) and inter-communal violence between Hindus and Muslims became endemic. Consequently, a decision was taken on 3 June 1947 to divide British India into two separate states, the Dominion of Pakistan compromising the Muslim majority areas and the Union of India comprising the rest. The two provinces Punjab and Bengal with large Muslim-majority areas were to be divided between the two dominions. An estimated 11 million people eventually migrated between the two parts of Punjab, and possibly 1 million perished in the inter-communal violence. Jammu and Kashmir, being adjascent to the Punjab province, was directly affected by the happenings in Punjab.

The original target date for the transfer of power to the new dominions was June 1948. However, fearing the rise of inter-communal violence, the British Viceroy Lord Mountbatten advanced the date to 15 August 1947. This gave only 6 weeks to complete all the arrangements for partition.[30] Mountbatten's original plan was to stay on the joint Governor General for both the dominions till June 1948. However, this was not accepted by the Pakistani leader Mohammad Ali Jinnah. In the event, Mountbatten stayed on as the Governor General of India, whereas Pakistan chose Jinnah as its Governor General.[31] It was envisaged that the division of the armed forces could not be completed by 15 August.[lower-alpha 1] It was decided that the British officers would stay on after the transfer of power. The service chiefs would be appointed by the Dominion governments and be responsible to them. The overall administrative, but not operational, control was vested with Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck, who was titled the Supreme Comander answerable to a Joint Defence Council. India appointed General Rob Lockhart as its Army chief and Pakistan appointed General Frank Messervy.[33]

The British also announced that, with the independence of the Dominions, the British Paramountcy over the princely states would come to and end. The rulers of the states were advised to join one of the two Dominions by executing an Instrument of Accession. Maharaja Hari Singh of Jammu and Kashmir, along with his prime minister Ram Chandra Kak, decided not to accede to either Dominion. The reasons cited were that the Muslim majority population of the State would not be comfortable with joining India, and that the Hindu and Sikh minorities would become vulnerable if the state joined Pakistan.[34]

Rebellion in Poonch

In the Poonch region, there was a large number of ex-servicemen who had served in the British Indian Army and World War II. Most of these ex-servicemen were of Sudhan origin and had long-standing dissident relations with the Dogra regime. On 21 April 1947, Hari Singh was invited to Rawalakot, where a large number of ex-servicemen turned up and paraded with their weapons. This triggered a series of defensive manoeuvers by Hari Singh to disarm the locals and enforce stricter military control. The Poonch region had around 60,000 ex-servicemen who were organising a 'home guard' that would attack the Dogra army at the right time. During the war, this group formed a war council in Murree and most of the ammunition was smuggled from Darra Adam Khel. A large number of fighters from Waziristan and the Federally Administered Tribal Areas were also inducted through local contacts and the Pakistan Army.[35]

The disenchanted Muslim population of Poonch and Mirpur revolted against Maharajah Hari Singh, and the situation in the State became increasingly tense following major communal violence and massacres of Muslims in the eastern districts of Jammu. One of India's pre-eminent journalists, G. K. Reddy, witnessed the mass killings of Muslims in Jammu's eastern districts.[36] A provisional 'Azad Kashmir' government was established at Palandri following the pro-Pakistan, anti-Maharajah revolt by the local population.[37] Azad Kashmir's government was left with 200,000 Muslim refugees from Jammu and Kashmir.[38]

Accession of Kashmir

Following the Muslim revolution in the Poonch and Mirpur area[21] and Pakistani backed[22]:18 Pashtun tribal intervention from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa aimed at supporting the revolution,[39][40] the Maharaja asked for Indian military assistance. India set the condition that Kashmir must accede to India for it to receive assistance. The Maharaja complied, and the Government of India recognised the accession of the princely state to India. Indian troops were sent to the state to defend it. The Jammu & Kashmir National Conference volunteers aided the Indian Army in its campaign to drive out the Pathan invaders.[41]

Pakistan refused to recognise the accession of Kashmir to India, claiming that it was obtained by "fraud and violence."[42] Governor General Mohammad Ali Jinnah ordered its Army Chief General Douglas Gracey to move Pakistani troops to Kashmir at once. However, the Indian and Pakistani forces were still under a joint command, and Field Marshal Auchinleck prevailed upon him to withdraw the order. With its accession to India, Kashmir became legally Indian territory, and the British officers could not a play any role in an inter-Dominion war.[43][44] The Pakistan army made available arms, ammunition and supplies to the rebel forces who were dubbed the `Azad Army'. Pakistani army officers `conveniently' on leave and the former officers of the Indian National Army were recruited to command the forces. In May 1948, the Pakistani army officially entered the conflict, in theory to defend the Pakistan borders, but it made plans to push towards Jammu and cut the lines of communications of the Indian forces in the Mehndar Valley.[45] In Gilgit, the force of Gilgit Scouts under the command of a British officer Major William Brown mutinied and overthrew the governor Ghansara Singh. Brown prevailed on the forces to declare accession to Pakistan.[46][47] They are also believed to have received assistance from the Chitral Scouts and the Chitral State Bodyguard's of the state of Chitral, one of the princely states of Pakistan, which had acceded to Pakistan on 6 October 1947.[48][49]

Stages of the war

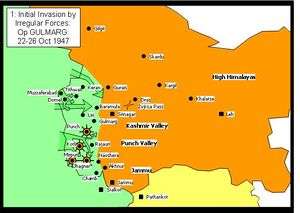

Initial invasion

The first clash occurred at Thorar on 3–4 October 1947.[35] On 22 October another attack was launched in the Muzaffarabad sector. The state forces stationed in the border regions around Muzaffarabad and Domel were quickly defeated by tribal forces (some Muslim state forces mutinied and joined them) and the way to the capital was open. Among the raiders, there were many active Pakistani Army soldiers disguised as tribals. They were also provided logistical help by the Pakistan Army. Rather than advancing toward Srinagar before state forces could regroup or be reinforced, the invading forces remained in the captured cities in the border region engaging in looting and other crimes against their inhabitants.[50] In the Poonch valley, the state forces retreated into towns where they were besieged.[51]

Indian operation in the Kashmir Valley

After the accession, India airlifted troops and equipment to Srinagar under the command of Lt. col. Dewan Ranjit Rai, where they reinforced the princely state forces, established a defence perimeter and defeated the tribal forces on the outskirts of the city. Initial defense operations included the notable defense of Badgam holding both the capital and airfield overnight against extreme odds. The successful defence included an outflanking manoeuvre by Indian armoured cars[52] during the Battle of Shalateng. The defeated tribal forces were pursued as far as Baramulla and Uri and these towns, too, were recaptured.

In the Poonch valley, tribal forces continued to besiege state forces.

In Gilgit, the state paramilitary forces, called the Gilgit Scouts, joined the invading tribal forces, who thereby obtained control of this northern region of the state. The tribal forces were also joined by troops from Chitral, whose ruler, Muzaffar ul-Mulk the Mehtar of Chitral, had acceded to Pakistan.[53][54][55]

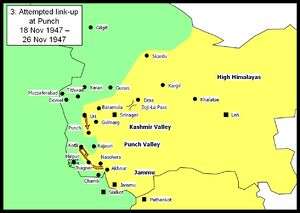

Attempted link-up at Poonch and fall of Mirpur

Indian forces ceased pursuit of tribal forces after recapturing Uri and Baramula, and sent a relief column southwards, in an attempt to relieve Poonch. Although the relief column eventually reached Poonch, the siege could not be lifted. A second relief column reached Kotli, and evacuated the garrisons of that town and others but were forced to abandon it being too weak to defend it. Meanwhile, Mirpur was captured by the tribal forces on 25 November 1947. Hindu women were reportedly abducted by tribal forces and taken into Pakistan. They were sold in the brothels of Rawalpindi. Around 400 women jumped into wells in Mirpur committing suicide to escape from being abducted.[56]

Fall of Jhanger and attacks on Naoshera and Uri

The tribal forces attacked and captured Jhanger. They then attacked Naoshera unsuccessfully, and made a series of unsuccessful attacks on Uri. In the south a minor Indian attack secured Chamb. By this stage of the war the front line began to stabilise as more Indian troops became available.

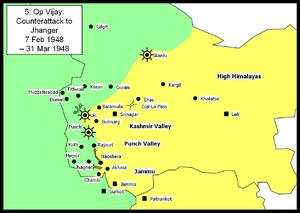

Operation Vijay: counterattack to Jhanger

The Indian forces launched a counterattack in the south recapturing Jhanger and Rajauri. In the Kashmir Valley the tribal forces continued attacking the Uri garrison. In the north Skardu was brought under siege by the Gilgit scouts.

Indian spring offensive

The Indians held onto Jhanger against numerous counterattacks, who were increasingly supported by regular Pakistani Forces. In the Kashmir Valley the Indians attacked, recapturing Tithwail. The Gilgit scouts made good progress in the High Himalayas sector, infiltrating troops to bring Leh under siege, capturing Kargil and defeating a relief column heading for Skardu.

Operations Gulab and Eraze

The Indians continued to attack in the Kashmir Valley sector driving north to capture Keran and Gurais (Operation Eraze).[22]:308–324 They also repelled a counterattack aimed at Tithwal. In the Jammu region, the forces besieged in Poonch broke out and temporarily linked up with the outside world again. The Kashmir State army was able to defend Skardu from the Gilgit Scouts impeding their advance down the Indus valley towards Leh. In August the Chitral Scouts and Chitral Bodyguard under Mata ul-Mulk besieged Skardu and with the help of artillery were able to take Skardu. This freed the Gilgit Scouts to push further into Ladakh.[57][58]

Operation Bison

During this time the front began to settle down. The siege of Poonch continued. An unsuccessful attack was launched by 77 Parachute Brigade (Brig Atal) to capture Zoji La pass. Operation Duck, the earlier epithet for this assault, was renamed as Operation Bison by Cariappa. M5 Stuart light tanks of 7 Cavalry were moved in dismantled conditions through Srinagar and winched across bridges while two field companies of the Madras Sappers converted the mule track across Zoji La into a jeep track. The surprise attack on 1 November by the brigade with armour supported by two regiments of 25 pounders and a regiment of 3.7-inch guns, forced the pass and pushed the tribal and Pakistani forces back to Matayan and later Dras. The brigade linked up on 24 November at Kargil with Indian troops advancing from Leh while their opponents eventually withdrew northwards toward Skardu.[59]:103–127 The Pakistani attacked the Skardu on 10 February 1948 which was repulsed by the Indian soldiers.[60] Thereafter, the Skardu Garrison was subjected to continuous attacks by the Pakistan Army for the next three months and each time, their attack was repulsed by the Colonel Sher Jung Thapa and his men.[60] Thapa held the Skardu with hardly 250 men for whole six long months without any reinforcement and replenishment.[61] On 14 August Indian General Sher Jung Thapa had to surrender Skardu to the Pakistani Army.[62] and raiders after a year long siege.[63]

Operation Easy; Poonch link-up

The Indians now started to get the upper hand in all sectors. Poonch was finally relieved after a siege of over a year. The Gilgit forces in the High Himalayas, who had previously made good progress, were finally defeated. The Indians pursued as far as Kargil before being forced to halt due to supply problems. The Zoji La pass was forced by using tanks (which had not been thought possible at that altitude) and Dras was recaptured.

Moves up to cease-fire

After protracted negotiations a cease-fire was agreed to by both countries, which came into effect. The terms of the cease-fire as laid out in a United Nations resolution[64] of 13 August 1948, were adopted by the UN on 5 January 1949. This required Pakistan to withdraw its forces, both regular and irregular, while allowing India to maintain minimum strength of its forces in the state to preserve law and order. On compliance of these conditions a plebiscite was to be held to determine the future of the territory. Indian losses were 1,500 killed and 3,500 wounded, whereas Pakistani losses were 6,000 killed and 14,000 wounded.[13] India gained control of the two-thirds Kashmir whereas, Pakistan gained roughly one-third of Kashmir.[25][65][66][67] Most neutral assessments agree that India was the victor of the war as it was able to successfully defend[23] about two thirds of Kashmir including Kashmir valley, Jammu and Ladakh.[24][25][26][27]

Military awards

Battle honours

After the war, a total of number of 11 battle honours and one theatre honour were awarded to units of the Indian Army, the notable amongst which are:[68]

|

|

|

Gallantry awards

For bravery, a number of soldiers and officers were awarded the highest gallantry award of their respective countries. Following is a list of the recipients of the Indian award Param Vir Chakra, and the Pakistani award Nishan-E-Haider:

- India

- Major Som Nath Sharma (Posthumous)

- Lance Naik Karam Singh

- Second Lieutenant Rama Raghoba Rane

- Naik Jadu Nath Singh

- Company Havildar Major Piru Singh Shekhawat

- Pakistan

See also

- Indo-Pakistani wars and conflicts

- Battle of Badgam

- Sino-Indian War

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

- Siachen war

- Kargil War

- Brigadier Mohammad Usman – Mahavir Chakra

Notes

References

- ↑ BBC on the 1947– 48 war

- ↑ Robert Blackwill, James Dobbins, Michael O'Hanlon, Clare Lockhart, Nathaniel Fick, Molly Kinder, Andrew Erdmann, John Dowdy, Samina Ahmed, Anja Manuel, Meghan O'Sullivan, Nancy Birdsall, Wren Elhai, Nicholas Burns (Editor), Jonathon Price (Editor). American Interests in South Asia: Building a Grand Strategy in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. Aspen Institute. pp. 155–. ISBN 978-1-61792-400-2. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ↑ Simon Ross Valentine (27 October 2008). Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at: History, Belief, Practice. Hurst Publishers. p. 204. ISBN 978-1850659167.

- 1 2 "Furqan Force". Persecution.org. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dasgupta, War and Diplomacy in Kashmir 2014

- ↑ Ganguly, Sumit (31 March 2016), Deadly Impasse, Cambridge University Press, pp. 134–, ISBN 978-0-521-76361-5

- ↑ "An extraordinary soldier", The Tribune – Spectrum, 21 June 2009

- 1 2 Nawaz, The First Kashmir War Revisited 2008

- ↑ Islam and the Ahmadiyya Jama'at: History, Belief, Practice. Columbia University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-231-70094-6, ISBN 978-0-231-70094-8

- ↑ "An incredible war: Indian Air Force in Kashmir war, 1947–48", by Bharat Kumar, Centre for Air Power Studies (New Delhi, India)

- ↑ By B. Chakravorty, "Stories of Heroism, Volume 1", p. 5

- ↑ By Sanjay Badri-Maharaj "The Armageddon Factor: Nuclear Weapons in the India-Pakistan Context", p. 18

- 1 2 3 4 With Honour & Glory: Wars fought by India 1947–1999, Lancer publishers

- ↑ "The News International: Latest News Breaking, Pakistan News". Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ India's Armed Forces: Fifty Years of War and Peace, p. 160

- ↑ Pakistan Covert Operations

- ↑ "Who changed the face of '47 war?". Times of India. 14 August 2005. Retrieved 14 August 2005.

- 1 2 3 Marin, Steve (2011). Alexander Mikaberidze, ed. Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 394. ISBN 978-1598843361.

- ↑ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003.

- 1 2 3 Kashmir in Encyclopædia Britannica (2011), online edition

- 1 2 Lamb, Alastair (1997), Incomplete partition: the genesis of the Kashmir dispute 1947–1948, Roxford, ISBN 0-907129-08-0

- 1 2 3 Prasad, S.N.; Dharm Pal (1987). History of Operations in Jammu and Kashmir 1947–1948. New Delhi: History Department, Ministry of Defence, Government of India. (printed at Thomson Press (India) Limited). p. 418.

- 1 2 Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004), A History of India (Fourth ed.), Routledge, p. 324,

The Indian army defended Kashmir against Pakistani aggression.

- 1 2 Wilcox, Wayne Ayres (1963), Pakistan: The Consolidation of a Nation, Columbia University Press, p. 66, ISBN 978-0-231-02589-8,

The war for states had not only ended in Indian military victory but had given its leaders enormous self-confidence and satisfaction over a job well done.

- 1 2 3 New Zealand Defence Quarterly, Issues 24–29. New Zealand. Ministry of Defence. 1999. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

India won, and gained two-thirds of Kashmir, which it successfully held against another Pakistani invasion in 1965.

- 1 2 Brozek, Jason (2008). War bellies: the critical relationship between resolve and domestic audiences. University of Wisconsin—Madison. p. 142. ISBN 978-1109044751. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

the 1947 First Kashmir (won by India, according to MIDS classification)

- 1 2 Hoontrakul, Pongsak (2014). The Global Rise of Asian Transformation: Trends and Developments in Economic Growth Dynamics (illustrated ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 9781137412355. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ Hutchison, J.; Vogel, Jean Philippe (1933). History of the Panjab Hill States. Superint., Gov. Print., Punjab. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Srinagar www.collectbritain.co.uk.

- ↑ Hodson, The Great Divide 1969, pp. 293, 320.

- ↑ Hodson, The Great Divide 1969, pp. 293, 329–330.

- ↑ Sarila, The Shadow of the Great Game 2007, p. 324.

- ↑ Hodson, The Great Divide 1969, pp. 262–265.

- ↑ Ankit, Henry Scott 2010, p. 45.

- 1 2 Regimental History Cell, History of the Azad Kashmir Regiment, Volume 1 (1947–1949), Azad Kashmir Regimental Centre, NLC Printers, Rawalpindi,1997

- ↑ Mathur, Shubh (2008). "Srinagar-Muzaffarabad-New York: A Kashmiri Family's Exile". In Roy, Anjali Gera; Bhatia, Nandi. Partitioned Lives: Narratives of Home, Displacement and Resettlement. Pearson Education India. p. 246. ISBN 9332506205.

- ↑ Kanth, Idrees. "The Untold Story of the People of Azad Kashmir – Book Review". Politics, Religion and Ideology. 14 (4): 589–591. doi:10.1080/21567689.2013.838477.

- ↑ Snedden, Christopher (2013). Kashmir:The Untold Story. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 9789350298985.

- ↑ Kashmir-konflikten. (18 October 2011) I Store norske leksikon. Taken from https://snl.no/Kashmir-konflikten

- ↑ Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation: Kashmir-konflikten

- ↑ My Life and Times. Allied Publishers Limited. Retrieved 2010-07-01.

- ↑ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 61.

- ↑ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 60.

- ↑ Connell, John (1959), Auchinleck: A Biography of Field-Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, Cassell

- ↑ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict 2003, p. 63.

- ↑ Brown, William (30 November 2014), Gilgit Rebelion: The Major Who Mutinied Over Partition of India, Pen and Sword, ISBN 978-1-4738-2187-3

- ↑ Martin Axmann, Back to the future: the Khanate of Kalat and the genesis of Baluch Nationalism 1915–1955 (2008), p. 273

- ↑ Tahir, M. Athar (2007-01-01). Frontier facets: Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province. National Book Foundation ; Lahore.

- ↑ Tom Cooper, I Indo-Pakistani War, 1947–1949, Air Combat Information Group, 29 October 2003

- ↑ Ministry of Defence, Government of India. Operations in Jammu and Kashmir 1947–1948. (1987). Thomson Press (India) Limited, New Delhi. This is the Indian Official History.

- ↑ "Defence of Srinagar 1947". Indian Defence Review. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Rahman, Fazlur (2007-01-01). Persistence and transformation in the Eastern Hindu Kush: a study of resource management systems in Mehlp Valley, Chitral, North Pakistan. In Kommission bei Asgard-Verlag. p. 32.

- ↑ Wilcox, Wayne Ayres (1963-01-01). Pakistan.

- ↑ Snedden, Christopher (2015-01-01). Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9781849043427.

- ↑ Tikoo, Colonel Tej K. (2013). "Genesis of Kashmir Problem and how it got Complicated: Events between 1931 and 1947 AD". Kashmir: Its Aborigines and their Exodus. New Delhi, Atlanta: Lancer Publishers. ISBN 1935501585.

- ↑ Singh, Harbakhsh (2000-01-01). In the Line of Duty: A Soldier Remembers. Lancer Publishers & Distributors. p. 227. ISBN 9788170621065.

- ↑ Bloeria, Sudhir S. (1997-12-31). The battles of Zojila, 1948. Har-Anand Publications. p. 72.

- ↑ Sinha, Lt. Gen. S.K. (1977). Operation Rescue:Military Operations in Jammu & Kashmir 1947–49. New Delhi: Vision Books. p. 174. ISBN 81-7094-012-5. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- 1 2 Malhotra, A. (2003). Trishul: Ladakh And Kargil 1947–1993. Lancer Publishers. p. 5. ISBN 9788170622963. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Khanna, Meera (2015). In a State of Violent Peace: Voices from the Kashmir Valley. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 9789351364832. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Khanna, Meera (2015). In a State of Violent Peace: Voices from the Kashmir Valley. HarperCollins Publisher. ISBN 9789351364832.

- ↑ Barua, Pradeep (2005). The State at War in South Asia. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 164–165. ISBN 9780803213449.

- ↑ "Resolution adopted by the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan on 13 August 1948.". Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- ↑ Hagerty, Devin (2005). South Asia in World Politics. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 161. ISBN 9780742525870. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ The Kingfisher History Encyclopedia. Kingfisher. 2004. p. 460. ISBN 9780753457849. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ Thomas, Raju (1992). Perspectives on Kashmir: the roots of conflict in South Asia. Westview Press. p. 25. ISBN 9780813383439. Retrieved 2016-03-06.

- ↑ Singh, Sarbans (1993). Battle Honours of the Indian Army 1757 – 1971. New Delhi: Vision Books. pp. 227–238. ISBN 81-7094-115-6. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

Bibliography

- Rakesh Ankit (May 2010). "Henry Scott: The forgotten soldier of Kashmir". Epilogue. 4 (5): 44–49.

- Dasgupta, C. (2014) [first published 2002], War and Diplomacy in Kashmir, 1947–48, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-81-321-1795-7

- Hodson, H. V. (1969), The Great Divide: Britain, India, Pakistan, London: Hutchinson

- Nawaz, Shuja (May 2008), "The First Kashmir War Revisited", India Review, 7 (2): 115–154, doi:10.1080/14736480802055455, (subscription required (help))

- Sarila, Narendra Singh (2007), The Shadow of the Great Game: The Untold Story of India's Partition, Constable, ISBN 978-1-84529-588-2

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1860648983

Further reading

- Major sources

- Ministry of Defence, Government of India. Operations in Jammu and Kashmir 1947–1948. (1987). Thomson Press (India) Limited, New Delhi. This is the Indian Official History.

- Lamb, Alastair. Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846–1990. (1991). Roxford Books. ISBN 0-907129-06-4.

- Praval, K.C. The Indian Army After Independence. (1993). Lancer International, ISBN 1-897829-45-0

- Sen, Maj Gen L.P. Slender Was The Thread: The Kashmir confrontation 1947–1948. (1969). Orient Longmans Ltd, New Delhi.

- Vas, Lt Gen. E. A. Without Baggage: A personal account of the Jammu and Kashmir Operations 1947–1949. (1987). Natraj Publishers Dehradun. ISBN 81-85019-09-6.

- Other sources

- Cohen, Lt Col Maurice. Thunder over Kashmir. (1955). Orient Longman Ltd. Hyderabad

- Hinds, Brig Gen SR. Battle of Zoji La. (1962). Military Digest, New Delhi.

- Sandhu, Maj Gen Gurcharan. The Indian Armour: History Of The Indian Armoured Corps 1941–1971. (1987). Vision Books Private Limited, New Delhi, ISBN 81-7094-004-4.

- Singh, Maj K Brahma. History of Jammu and Kashmir Rifles (1820–1956). (1990). Lancer International New Delhi, ISBN 81-7062-091-0.

- Ayub, Muhammad (2005). An army, Its Role and Rule: A History of the Pakistan Army from Independence to Kargil, 1947–1999. RoseDog Books. ISBN 9780805995947.