Charles I of Austria

| Charles I & IV | |

|---|---|

| |

| Emperor of Austria King of Hungary and Croatia King of Bohemia | |

| Reign | 21 November 1916 – 3 April 1919 |

| Coronation | 30 December 1916 |

| Predecessor | Emperor Franz Joseph I |

| Successor | monarchy abolished |

| Prime Ministers |

|

| Born |

17 August 1887 Persenbeug Castle, Persenbeug-Gottsdorf, Lower Austria, Austria-Hungary |

| Died |

1 April 1922 (aged 34) Madeira, Portuguese Republic |

| Burial |

Igreja Nossa Senhora do Monte, Madeira Heart buried in Muri Abbey, Switzerland |

| Spouse | Princess Zita of Bourbon-Parma |

| Issue | |

| House | Habsburg |

| Father | Archduke Otto of Austria |

| Mother | Princess Maria Josepha of Saxony |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Charles I (Karl Franz Joseph Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Marie; 17 August 1887 – 1 April 1922) was the last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He was the last Emperor of Austria, the last King of Hungary (as Charles IV),[1] and the last monarch belonging to the House of Habsburg-Lorraine. After his uncle Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in 1914, Charles I reigned from 1916 until 1919 when he "renounced participation" in state affairs, but did not abdicate. He spent the remaining years of his life attempting to restore the monarchy until his death in 1922. Following his beatification by the Catholic Church in 2004, he has become commonly known as Blessed Charles of Austria.

Early life

Charles was born 17 August 1887 in the Castle of Persenbeug in Lower Austria. His parents were Archduke Otto Franz of Austria and Princess Maria Josepha of Saxony. At the time, his granduncle Franz Joseph reigned as Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary, and his uncle Franz Ferdinand became heir presumptive two years later.

As a child, Archduke Charles was reared a devout Roman Catholic. He spent his early years wherever his father's regiment happened to be stationed; later on he lived in Vienna and Reichenau an der Rax. He was privately educated, but, contrary to the custom ruling in the imperial family, he attended a public gymnasium for the sake of demonstrations in scientific subjects. On the conclusion of his studies at the gymnasium, he entered the army, spending the years from 1906 to 1908 as an officer chiefly in Prague, where he studied law and political science concurrently with his military duties.[2]

In 1907, he was declared of age and Prince Zdenko Lobkowitz was appointed his chamberlain. In the next few years he carried out his military duties in various Bohemian garrison towns. Charles's relations with his granduncle were not intimate, and those with his uncle Franz Ferdinand were not cordial, with the differences between their wives increasing the existing tension between them. For these reasons, Charles, up to the time of the assassination of his uncle in 1914, obtained no insight into affairs of state, but led the life of a prince not destined for a high political position.[2]

Marriage

In 1911, Charles married Princess Zita of Bourbon-Parma. They had met as children but did not see one another for almost ten years, as each pursued their education. In 1909, his Dragoon regiment was stationed at Brandýs nad Labem (Brandeis an der Elbe) in Bohemia, from where he visited his aunt at Franzensbad.[3]:5 It was during one of these visits that Charles and Zita became reacquainted.[3]:5 Due to Franz Ferdinand's morganatic marriage in 1900, his children were excluded from the succession. As a result, the Emperor severely pressured Charles to marry. Zita not only shared Charles' devout Catholicism, but also an impeccably royal lineage.[4]:16 Zita later recalled:

| “ | We were of course glad to meet again and became close friends. On my side feelings developed gradually over the next two years. He seemed to have made his mind up much more quickly, however, and became even more keen when, in the autumn of 1910, rumours spread about that I had got engaged to a distant Spanish relative, Jaime, Duke of Madrid. On hearing this, the Archduke came down post haste from his regiment at Brandeis and sought out his [step]grandmother, Archduchess Maria Theresa, who was also my aunt and the natural confidante in such matters. He asked if the rumor was true and when told it was not, he replied, "Well, I had better hurry in any case or she will get engaged to someone else."[3]:8 | ” |

Heir presumptive

Charles became heir presumptive after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914, the event which precipitated World War I. Only at this time did the old Emperor take steps to initiate the heir-presumptive to his crown in affairs of state. But the outbreak of World War I interfered with this political education. Charles spent his time during the first phase of the war at headquarters at Teschen, but exercised no military influence.[2]

Charles then became a Generalfeldmarschall in the Austro-Hungarian Army. In the spring of 1916, in connection with the offensive against Italy, he was entrusted with the command of the XX. Corps, whose affections the heir-presumptive to the throne won by his affability and friendliness. The offensive, after a successful start, soon came to a standstill. Shortly afterwards, Charles went to the eastern front as commander of an army operating against the Russians and Romanians.[2]

Reign

Charles succeeded to the thrones in November 1916, after the death of his grand-uncle, Emperor Franz Joseph.

On 2 December 1916, he assumed the title of Supreme Commander of the whole army from Archduke Friedrich. His coronation as King of Hungary occurred on 30 December. In 1917, Charles secretly entered into peace negotiations with France. He employed his brother-in-law, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon-Parma, an officer in the Belgian Army, as intermediary.

Although his foreign minister, Ottokar Czernin, was only interested in negotiating a general peace which would include Germany, Charles himself went much further in suggesting his willingness to make a separate peace. When news of the overture leaked in April 1918, Charles denied involvement until French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau published letters signed by him. This led to Czernin's resignation, forcing Austria-Hungary into an even more dependent position with respect to its seemingly wronged German ally.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was wracked by inner turmoil in the final years of the war, with much tension between ethnic groups. As part of his Fourteen Points, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson demanded that the Empire allow for autonomy and self-determination of its peoples. In response, Charles agreed to reconvene the Imperial Parliament and allow for the creation of a confederation with each national group exercising self-governance. However, the ethnic groups fought for full autonomy as separate nations, as they were now determined to become independent from Vienna at the earliest possible moment.

Foreign minister Baron Istvan Burián asked for an armistice 14 October based on the Fourteen Points, and two days later Charles issued a proclamation that radically changed the nature of the Austrian state. The Poles were granted full independence with the purpose of joining their ethnic brethren in Russia and Germany in a Polish state. The rest of the Austrian lands were transformed into a federal union composed of four parts: German, Czech, South Slav, and Ukrainian. Each of the four parts was to be governed by a federal council, and Trieste was to have a special status. However, Secretary of State Robert Lansing replied four days later that the Allies were now committed to the causes of the Czechs, Slovaks and South Slavs. Therefore, autonomy for the nationalities was no longer enough. In fact, a Czechoslovak provisional government had joined the Allies 14 October, and the South Slav national council declared an independent South Slav state 29 October 1918.

Trialism and Croatia

Since the beginning of his rule he favored the creation of third Croatian political entity, in his Croatian Coronation oath from 1916 he recognized the union of the Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Dalmatia and Slavonia with Rijeka[5] and during his short reign supported trialist suggestions from the Croatian Sabor and Ban, but the suggestions were always vetoed by the Hungarian side which did not want to share power with other nations. After Emperor Karl's manifesto of 14 October 1918 was rejected by the declaration of the National Council in Zagreb.[6] President of the Croatian pro-monarchy political party Pure Party of Rights Dr. Aleksandar Horvat, with other parliament members and generals went to visit the emperor on 21 October 1918 in Bad Ischl,[7][8] where the emperor agreed and signed the trialist manifest under the proposed terms set by the delegation, on the condition that the Hungarian part does the same since he swore an oath on the integrity of the Hungarian crown.[9][10][11] The delegation went the next day to Budapest where it presented the manifest to Hungarian officials and Council of Ministers who signed the manifest and released the king from his oath, creating a third Croatian political entity (Zvonimir's kingdom)[10][12][13][14] After the signing, two parades were held in Zagreb, one for the ending of the K.u.K. monarchy, which was held in front of the Croatian National Theater, and another one for saving the trialist monarchy.[12] The last vote for the support of the trialist reorganization of the empire was, however, too late. On 29 October 1918, the Croatian Sabor (parliament) ended the union and all ties with Hungary and Austria, proclaimed the unification of all Croatian lands and entered the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.[15] The curiosity is that no act of Sabor dethroned King Karl IV, nor did it acknowledge the entering in a state union with Serbia, which is today mentioned in the preamble of the Constitution of Croatia.[16]

The Lansing note effectively ended any efforts to keep the Empire together. One by one, the nationalities proclaimed their independence; even before the note the national councils had been acting more like provisional governments. Charles' political future became uncertain. On 31 October, Hungary officially ended the personal union between Austria and Hungary. Nothing remained of Charles' realm except the predominantly German-speaking Danubian and Alpine provinces, and he was challenged even there by the German Austrian State Council. His last Austrian prime minister, Heinrich Lammasch, advised him that he was an impossible situation, and his best course was to temporarily give up his right to exercise sovereign power.

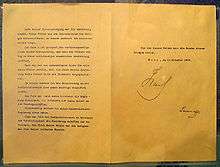

Proclamation of 11 November

On 11 November 1918, the same day as the armistice ending the war between the Allied Powers and Germany was signed, Charles issued a carefully worded proclamation in which he recognized the Austrian people's right to determine the form of the state and "relinquish(ed) every participation in the administration of the State."[17] He also released his officials from their oath of loyalty to him. On the same day the Imperial Family left Schönbrunn Palace and moved to Castle Eckartsau, east of Vienna. On 13 November, following a visit of Hungarian magnates, Charles issued a similar proclamation for Hungary.

Although it has widely been cited as an "abdication", that word was never mentioned in either proclamation.[18] Indeed, he deliberately avoided using the word abdication in the hope that the people of either Austria or Hungary would vote to recall him.

Privately, Charles left no doubt that he believed himself to be the rightful emperor. Addressing Cardinal Friedrich Gustav Piffl, he wrote:

I did not abdicate, and never will. (...) I see my manifesto of 11 November as the equivalent to a cheque which a street thug has forced me to issue at gunpoint. (...) I do not feel bound by it in any way whatsoever.[19]

Instead, on 12 November, the day after he issued his proclamation, the independent Republic of German-Austria was proclaimed, followed by the proclamation of the Hungarian Democratic Republic on 16 November. An uneasy truce-like situation ensued and persisted until 23–24 March 1919, when Charles left for Switzerland, escorted by the commander of the small British guard detachment at Eckartsau, Lt. Col. Edward Lisle Strutt. As the Imperial Train left Austria on 24 March, Charles issued another proclamation in which he confirmed his claim of sovereignty, declaring that "whatever the national assembly of German Austria has resolved with respect to these matters since 11 November is null and void for me and my House."[20]

Although the newly established republican government of Austria was not aware of this "Manifesto of Feldkirch" at this time (it had been dispatched only to the Spanish King Alfonso XIII and to the Pope Benedict XV through diplomatic channels), the politicians now in power were extremely irritated by the Emperor's departure without an explicit abdication. The Austrian Parliament passed the Habsburg Law on 3 April 1919, which permanently barred Charles and Zita from returning to Austria. Other Habsburgs were banished from Austrian territory unless they renounced all intentions of reclaiming the throne and accepted the status of ordinary citizens. Another law, passed on the same day, abolished all nobility in Austria.

In Switzerland, Charles and his family briefly took residence at Castle Wartegg near Rorschach at Lake Constance and later moved to Château de Prangins at Lake Geneva on 20 May 1919.

Attempts to reclaim throne of Hungary

Encouraged by Hungarian royalists ("legitimists"), Charles sought twice in 1921 to reclaim the throne of Hungary, but failed largely because Hungary's regent, Miklós Horthy (the last admiral of the Austro-Hungarian Navy), refused to support him. Horthy's failure to support Charles' restoration attempts is often described as "treasonous" by royalists. Critics suggest that Horthy's actions were more firmly grounded in political reality than those of Charles and his supporters. Indeed, the neighbouring countries had threatened to invade Hungary if Charles tried to regain the throne. Later in 1921, the Hungarian parliament formally nullified the Pragmatic Sanction, an act that effectively dethroned the Habsburgs.

Exile in Madeira and death

After the second failed attempt at restoration in Hungary, Charles and his pregnant wife Zita were briefly quarantined at Tihany Abbey. On 1 November 1921 they were taken to the Hungarian Danube harbor city of Baja, were made to board the British monitor HMS Glowworm and there removed to the Black Sea where they were transferred to the light cruiser HMS Cardiff.[21][22] They arrived at their final exile, the Portuguese island of Madeira on 19 November 1921. Determined to prevent a third restoration attempt, the Council of Allied Powers had agreed on Madeira because it was isolated in the Atlantic and easily guarded.[23]

Originally the couple and their children, who joined them on 2 February 1922, lived at Funchal at the Villa Vittoria, next to Reid's Hotel and later moved to Quinta do Monte. Compared to the imperial glory in Vienna and even at Eckartsau, conditions there were certainly impoverished.[24]

Charles did not leave Madeira again. On 9 March 1922 he had caught a cold walking into town, which developed into bronchitis and subsequently progressed to severe pneumonia. Having suffered two heart attacks, he died of respiratory failure on April 1, in the presence of his wife (who was pregnant with their eighth child) and nine-year-old Crown Prince Otto, remaining conscious almost until his last moments.[25] His remains except for his heart are still interred on the island, in the Church of Our Lady of Monte, in spite of several attempts to move them to the Habsburg Crypt in Vienna. His heart and the heart of his wife are entombed in Muri Abbey, Switzerland.

Assessment

Historians have been mixed in their evaluations of Charles and his reign. One of the most critical has been Helmut Rumpler, head of the Habsburg commission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, who has described Charles as "a dilettante, far too weak for the challenges facing him, out of his depth, and not really a politician." However, others have seen Charles as a brave and honourable figure who tried as Emperor-King to halt World War I. The English writer, Herbert Vivian, wrote:

"Karl was a great leader, a Prince of peace, who wanted to save the world from a year of war; a statesman with ideas to save his people from the complicated problems of his Empire; a King who loved his people, a fearless man, a noble soul, distinguished, a saint from whose grave blessings come."

Furthermore, Anatole France, the French novelist, stated:

"Emperor Karl is the only decent man to come out of the war in a leadership position, yet he was a saint and no one listened to him. He sincerely wanted peace, and therefore was despised by the whole world. It was a wonderful chance that was lost."

Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, who at the time of Charles' reign was the commander in chief of the Imperial German Army, commented in his memoirs:

"He tried to compensate for the evaporation of the ethical power which emperor Franz Joseph had represented by offering ethnical reconciliation. Even as he dealt with elements who were sworn to the goal of destroying his empire he believed that his acts of political grace would affect their conscience. These attempts were totally futile; those people had long ago lined up with our common enemies, and were far from being deterred."[26]

Beatification

| Blessed Charles of Austria-Hungary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Emperor; Layman | |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 3 October 2004, Saint Peter's Square, Vatican City by Pope John Paul II |

| Feast | 21 October |

| Attributes |

|

Catholic Church leaders have praised Charles for putting his Christian faith first in making political decisions, and for his role as a peacemaker during the war, especially after 1917. They have considered that his brief rule expressed Roman Catholic social teaching, and that he created a social legal framework that in part still survives.

Pope John Paul II declared Charles "Blessed" in a beatification ceremony held on 3 October 2004,[27] and stated:

The decisive task of Christians consists in seeking, recognizing and following God's will in all things. The Christian statesman, Charles of Austria, confronted this challenge every day. To his eyes, war appeared as "something appalling". Amid the tumult of the First World War, he strove to promote the peace initiative of my Predecessor, Benedict XV.[28]

From the beginning, the Emperor Charles conceived of his office as a holy service to his people. His chief concern was to follow the Christian vocation to holiness also in his political actions. For this reason, his thoughts turned to social assistance.

The cause or campaign for his canonization began in 1949, when testimony of his holiness was collected in the Archdiocese of Vienna. In 1954, the cause was opened and he was declared "servant of God", the first step in the process. The League of Prayers established for the promotion of his cause has set up a website,[29] and Cardinal Christoph Schönborn of Vienna has sponsored the cause.

Recent milestones

- On 14 April 2003, the Vatican's Congregation for the Causes of Saints in the presence of Pope John Paul II, promulgated Charles of Austria's "heroic virtues," and he thereby acquired the title of venerable.

- On 21 December 2003, the Congregation certified, on the basis of three expert medical opinions, that a miracle in 1960 occurred through the intercession of Charles. The miracle attributed to Charles was the scientifically inexplicable healing of a Brazilian nun with debilitating varicose veins; she was able to get out of bed after she prayed for his beatification.

- On 3 October 2004, he was beatified by Pope John Paul II. The Pope also declared 21 October, the date of Charles' marriage in 1911 to Princess Zita, as Charles' feast day. The beatification has caused controversy because Charles authorized the Austro-Hungarian Army's use of poison gas during World War I.[30][31]

- On 31 January 2008, a Church tribunal, after a 16-month investigation, formally recognized a second miracle attributed to Charles I (required for his canonization as a saint in the Catholic Church); in an uncommon twist, the Florida woman claiming the miracle cure was not Catholic, but Baptist. However, due to her experiences, she converted to Catholicism soon thereafter.[32][33]

Quotes

- "Now, we must help each other to get to Heaven."[34] Addressing Empress Zita on 22 October 1911, the day after their wedding.

- "I am an officer with all my body and soul, but I do not see how anyone who sees his dearest relations leaving for the front can love war."[35] Addressing Empress Zita after the outbreak of World War I.

- "I have done my duty, as I came here to do. As crowned King, I not only have a right, I also have a duty. I must uphold the right, the dignity and honor of the Crown.... For me, this is not something light. With the last breath of my life I must take the path of duty. Whatever I regret, Our Lord and Savior has led me."[36] Addressing Cardinal János Csernoch after the defeat of his attempt to regain the Hungarian throne in 1921. The British Government had vainly hoped that the Cardinal would be able to persuade him to renounce his title as King of Hungary.

- "I must suffer like this so my people will come together again."[37] Spoken in Madeira, during his last illness.

- "I can't go on much longer... Thy will be done... Yes... Yes... As you will it... Jesus!"[38] Reciting his last words while contemplating a crucifix held by Empress Zita.

Titles, styles, honours and arms

| Styles of Charles I of Austria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty |

| Alternative style | Sir |

Titles and styles

- 17 August 1887 – 21 November 1916: His Imperial and Royal Highness Archduke and Prince Charles of Austria, Prince of Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia[39]

- 21 November 1916 – 3 April 1919: His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty The Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary and Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia[40]

- 3 April 1919 – 1 April 1922:

- His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty Emperor Charles of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary (used outside Austria)

- Karl Habsburg-Lothringen (used in Austria)

Official grand title

His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty,

Charles the First,

By the Grace of God, Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, of this name the Fourth, King of Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia, and Galicia, Lodomeria, and Illyria; King of Jerusalem, Archduke of Austria; Grand Duke of Tuscany and Cracow, Duke of Lorraine and of Salzburg, of Styria, of Carinthia, of Carniola and of the Bukovina; Grand Prince of Transylvania; Margrave of Moravia; Duke of Upper and Lower Silesia, of Modena, Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla, of Auschwitz and Zator, of Teschen, Friuli, Ragusa and Zara; Princely Count of Habsburg and Tyrol, of Kyburg, Gorizia and Gradisca; Prince of Trent and Brixen; Margrave of Upper and Lower Lusatia and in Istria; Count of Hohenems, Feldkirch, Bregenz, Sonnenberg; Lord of Trieste, of Cattaro, and in the Windic March; Grand Voivode of the Voivodship of Serbia.

Honours

- Charles was Grand Master of the following Orders:

- Gold Medal of Military Merit (Signum Laudis)

- Military Cross for the 60th year of the reign of Franz Joseph

- Foreign decorations

-

.svg.png) Prussia: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle

Prussia: Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle -

.svg.png) Prussia: Pour le Mérite

Prussia: Pour le Mérite -

.svg.png) Prussia: Iron Cross

Prussia: Iron Cross -

.svg.png) Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of Max Joseph

Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of Max Joseph -

.svg.png) Kingdom of Saxony: Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of St. Henry

Kingdom of Saxony: Knight Grand Cross of the Military Order of St. Henry -

Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion

Sovereign Military Order of Malta: Bailiff Grand Cross of Honour and Devotion

Children

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crown Prince Otto | 20 November 1912 | 4 July 2011 (aged 98) | married (1951) Princess Regina of Saxe-Meiningen (1925–2010); seven children. |

| Archduchess Adelheid | 3 January 1914 | 2 October 1971 (aged 57) | |

| Archduke Robert | 8 February 1915 | 7 February 1996 (aged 80) | married (1953) Princess Margherita of Savoy-Aosta (born 7 April 1930); five children. |

| Archduke Felix | 31 May 1916 | 6 September 2011 (aged 95) | married (1952) Princess Anna-Eugénie of Arenberg (5 July 1925 – 9 June 1997); seven children. |

| Archduke Karl Ludwig | 10 March 1918 | 11 December 2007 (aged 89) | married (1950) Princess Yolanda of Ligne (born 6 May 1923); four children. |

| Archduke Rudolf | 5 September 1919 | 15 May 2010 (aged 90) | married (1953) Countess Xenia Tschernyschev-Besobrasoff (11 June 1929 – 20 September 1968); four children. Second marriage (1971) Princess Anna Gabriele of Wrede (born 11 September 1940); one child. |

| Archduchess Charlotte | 1 March 1921 | 23 July 1989 (aged 68) | married (1956) George, Duke of Mecklenburg (5 October [O.S. 22 September] 1899 – 6 July 1963). |

| Archduchess Elisabeth | 31 May 1922 | 7 January 1993 (aged 70) | married (1949) Prince Heinrich Karl Vincenz of Liechtenstein (5 August 1916 – 17 April 1991), grandson of Prince Alfred; five children. |

Ancestors

See also

- Otto von Habsburg, Charles' oldest son and head of the Habsburg family until 2011

- Ukrainian Austrian internment

- List of heirs to the Austrian throne

Notes

- ↑ "Charles (I)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- 1 2 3 4

Pribram, Alfred Francis (1922). "Charles". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York.

Pribram, Alfred Francis (1922). "Charles". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). London & New York. - 1 2 3 Beeche.

- ↑ Brook-Shepherd, Gordon (1991). The last empress: the life and times of Zita of Austria-Hungary, 1892–1989. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-215861-2.

- ↑ (Hrvatska) Krunidbena zavjernica Karla IV. hrvatskom Saboru 28. prosinca 1916. (sa grbom Dalmacije, Hrvatske, Slavonije i Rijeke iznad teksta), str. 1.-4. Hrvatski Državni Arhiv./ENG. (Croatian) Coronation oath of Karl IV to Croatian Sabor (parliament), 28th December 1916. (with coat of arms of Dalmatia, Croatia, Slavonia and Rijeka above the text), p.1-4 Croatian State Archives

- ↑ F. Šišić Dokumenti, p.180.

- ↑ Vasa Kazimirović NDH u svetlu nemačkih dokumenata i dnevnika Gleza fon Horstenau 1941 – 1944, Beograd 1987., p.56.-57.

- ↑ Jedna Hrvatska ‘H. Rieči’", 1918., no. 2167

- ↑ A. Pavelić (lawyer) Doživljaji, p.432.

- 1 2 Dr. Aleksandar Horvat Povodom njegove pedesetgodišnjice rodjenja, Hrvatsko pravo, Zagreb, 17/1925., no. 5031

- ↑ Edmund von Glaise-Horstenau,Die Katastrophe. Die Zertrümmerung Österreich-Ungarns und das Werden der Nachfolgestaaten, Zürich – Leipzig – Wien 1929, p.302-303.

- 1 2 Budisavljević Srđan, Stvaranje Države SHS, (Creaton of the state of SHS), Zagreb, 1958, p. 132.-133.

- ↑ F. Milobar Slava dr. Aleksandru Horvatu!, Hrvatsko pravo, 20/1928., no. 5160

- ↑ S. Matković, "Tko je bio Ivo Frank?", Politički zatvorenik, Zagreb, 17/2007., no. 187, 23.

- ↑ Hrvatska Država, newspaper Public proclamation of the Sabor 29.10.1918. Issued 29.10.1918. no. 299. p.1.

- ↑ Narodne novine, br. 56/90, 135/97, 8/98 – pročišćeni tekst, 113/2000, 124/2000 – pročišćeni tekst, 28/2001, 41/2001 – pročišćeni tekst, 55/2001 – ispravak

- ↑ Duffy, Michael (22 August 2009). "Primary Documents - Emperor Karl I's Abdication Proclamation, 11 November 1918". First World War.com. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- ↑ Gombás, István (2002). Kings and Queens of Hungary & Princes of Transylvania. Budapest: Corvina. ISBN 963-13-5152-1.

- ↑ Scheidl, Hans Werner (7 November 2008). "Abdanken? Nie – nie – nie!" [Abdication? Never - never - never!]. Die Presse (in German). Vienna. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ Portisch H: Österreich I. Die unterschätzte Republik. Verlag Kremayr & Scheriau, Vienna 1989. p. 117

- ↑ Brook-Shepherd, Gordon (17 January 2004). Uncrowned Emperor - The Life and Times of Otto von Habsburg. London: Hambledon & London. ISBN 978-1852854393. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Charles Carried into Exile on a British Ship As Napoleon Was; Zita to Bear Another Heir". The New York Times. 5 November 1921. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ "Charles St. Helena Likely to be Funcha". The New York Times. 6 November 1921. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ Blessed Emperor Charles, Prince of Peace for a United Europe. Archdiocese of Vienna K1238/05. 6 July 2005.

- ↑ "Charles of Austria Dies of Pneumonia in exile on Madera". The New York Times. Associated Press. 2 April 1922. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ Hindenburg, Paul von (1920). download Aus meinem Leben [In My Life] Check

|url=value (help) (PDF) (in German). Leipzig: S. Hirzel. p. 163 (pdf page 165). - ↑ Sondhaus, Lawrence (29 April 2011). World War One: The Global Revolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 483. ISBN 978-0521736268. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "Beatification of Five Servants of God; Homily of John Paul II". 3 October 2004. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011.

- ↑ "Kaiser Karl Gebetsliga für den Völkerfrieden" [Emperor Charles Prayer League for the Harmony of Peoples] (in German). Emperor-charles.org. 2011. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ "Emperor and mystic nun beatified". BBC News. 3 October 2004. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ "Historiker: Giftgas-Einsatzbefehl durch Karl I. war "Notwehr"" [Historian: poison gas use command by Charles I was "self-defense"]. Der Standard. 5 October 2004. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ Goodman, Tanya (8 February 2008). "Miracle in our midst: Central Florida woman's cure may lead to sainthood for Blessed Karl of Austria". Florida Catholic.

- ↑ Pinsky, Mark I. (8 February 2008). "Baptist woman from Kissimmee edges Austro-Hungarian emperor toward Roman Catholic sainthood". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ Bogle, James and Joanna (5 September 2005). "A Heart for Europe: The Lives of Emperor Charles and Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary". Gracewing Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-0852441732.

- ↑ Bogle 2005, p. 54.

- ↑ Bogle 2005, p. 137.

- ↑ Bogle 2005, p. 143.

- ↑ Bogle 2005, p. 144.

- ↑ Kaiser Joseph II. harmonische Wahlkapitulation mit allen den vorhergehenden Wahlkapitulationen der vorigen Kaiser und Könige. Since 1780 official title used for princes ("zu Ungarn, Böhmen, Dalmatien, Kroatien, Slawonien, Königlicher Erbprinz")

- ↑ Croatian Coronation Oath of 1916. P.2-4, "Emperor of Austria, Hungary and Croatia, Slavonia and Dalmatia Apostolic King"

Further reading

- G. Brook-Shepherd, The Last Empress: The Life & Times of Zita of Austria-Hungary, 1892–1989, 1991. ISBN 0-00-215861-2.

- (Italian) Flavia Foradini, Otto d'Asburgo. L'ultimo atto di una dinastia, mgs press, Trieste: 2004. ISBN 88-89219-04-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Karl I of Austria. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles I of Austria. |

| Charles I of Austria Cadet branch of the House of Lorraine Born: 17 August 1887 Died: 1 April 1922 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Franz Joseph I |

Emperor of Austria 1916–1918 |

Abolition of monarchy |

| King of Hungary 1916–1918 |

Vacant | |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Franz Joseph I |

Head of State of Austria as Emperor of Austria 1916–1918 |

Succeeded by Karl Seitz as President of Austria |

| Head of State of Hungary as King of Hungary 1916–1918 |

Succeeded by Mihály Károlyi as Provisional President of Hungary | |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Titles extant before Dissolution of Austria-Hungary |

— TITULAR — Emperor of Austria King of Hungary 1918 – 1 April 1922 |

Succeeded by Crown Prince Otto |

| Preceded by Franz Ferdinand |

— TITULAR — Duke of Modena Archduke of Austria-Este 28 June 1914 – 16 April 1917 Reason for succession failure: Title abolished in 1860 |

Succeeded by Robert |

.svg.png)