Kato Akourdhalia

| Kato Akourdhalia Κάτω Ακουρδάλια | |

|---|---|

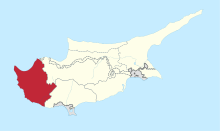

Kato Akourdhalia Location in Cyprus | |

| Coordinates: 34°57′10″N 32°27′6″E / 34.95278°N 32.45167°ECoordinates: 34°57′10″N 32°27′6″E / 34.95278°N 32.45167°E | |

| Country |

|

| District | Paphos District |

| Population (2001)[1] | |

| • Total | 32 |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) |

| Postal code | 6334 |

Kato Akourdhalia (Greek: Κάτω Ακουρδάλια) is a village in the Paphos District of Cyprus, located 2 km northwest of Miliou.

The name 'Akourdhalia' has several purported roots. The first is from the French 'a cour de l'eau', meaning "in the course of the water", which hearkens back to the time of the Kingdom of Cyprus where Provençal was spoken as well as Cypriot Greek. Another interpretation refers to the local dialect word 'korda', that has two possible meanings. The first is the long strong rope made in the village and the second, for wild garlic which grows in abundance in the surrounding fields. Nearchos Klerides, who extensively researched the origins of names of towns and villages in Cyprus, believed in the "string" interpretation of "korda" as a special belt that the villagers or the members of the Lusignan battalion wore around their waist. A final interpretation is the combination of two Greek words translating to 'listen to the birds'. A point to note is that during the Venetian rule of Cyprus (1489 - 1571) the village is recorded under the name Quardia.

On the outskirts of Kato Akourdhalia is a track which leads to the recently restored church of Ayia Paraskevi which is said to date back to the 15th century. Originally, the church was full of frescoes but now most of them are faded or have totally disappeared. There is a stone altar inside with the remains of an old icon dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

In amongst the traditionally-styled whitewashed houses nestling between almond trees, there is a small coffee shop in Kato Akourdhalia. Also to be found is what used to be the village manor house, which has a rich history dating back over a hundred years. The building has since been renovated and converted into a group of self-catering suites for holidaymakers with a restaurant downstairs offering traditional Cypriot cuisine.

The Museum of Folk Art is situated high on the hillside in the old schoolhouse. The museum houses various interesting artefacts from years gone by, many of which were used to cultivate small areas of land with wheat, chickpeas and barley. There are hand ploughs with stout wooden shafts and several large metal sieves used for sifting the soil. There are traditional costumes too, and there are faded old photographs of the village men resplendent in their vrakas and stout leather boots and the women in dresses of striped hand-woven cotton with matching headscarves and large protective aprons. The villagers would wear these costumes for all big celebrations and would weave the cloth on large wooden looms like the one that stands proudly in the corner, as well as making colourful rugs for the walls and floors of their homes.

Outside the museum, a traditional clay bread oven can be seen with its smaller side oven that is used to cook the popular local dish kleftiko, which is chunks of lamb that are baked slowly in terracotta pots with marjoram. Close by, stands a zivania still which was used at the end of the grape harvest to make the local variety of fire water. As well as making your head spin, zivania is also known for its medicinal properties. So you can either drink the stuff to forget about your aches and pains, or rub it into any sore areas – the end result is the same.

Rupert Gunnis, describing the village in 1936, stated that:

"The lower village... contains a ruined chapel dedicated to the Panagia. It is also known as the Church of the Hill Covered with Shrubs. A curious legend lingers in the village of a wealthy and eccentric Englishman who lived here in the early years of the nineteenth century, and his house is still pointed out by the villagers."[2]

References

- ↑ Census 2001

- ↑ Rupert Gunnis, Historic Cyprus, 1936, p.155