Langcliffe

| Langcliffe | |

Langcliffe Village Institute |

|

Langcliffe |

|

| Population | 333 |

|---|---|

| OS grid reference | SD822650 |

| Civil parish | Langcliffe |

| District | Craven |

| Shire county | North Yorkshire |

| Region | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Postcode district | BD24 |

| Dialling code | 01729 |

| Police | North Yorkshire |

| Fire | North Yorkshire |

| Ambulance | Yorkshire |

| EU Parliament | Yorkshire and the Humber |

| UK Parliament | Skipton and Ripon |

Coordinates: 54°04′52″N 2°16′23″W / 54.081°N 2.273°W

Langcliffe is a village and civil parish in the Craven district of North Yorkshire, England. It is situated north of Settle, and to the east of Giggleswick. Langcliffe lies within one of eight regions covered by the Yorkshire Dales National Park, which was "established in 1954, and covers an area of 1,762 square kilometres in the north of England, straddling the central Pennines in the counties of North Yorkshire and Cumbria."[1] The River Ribble runs parallel to the east of Langcliffe. The area had a population of 333 according to the 2011 census.[2] Notable residents or former residents of this village include authors Leah Fleming and Marina Fiorato.

History

Pre-historic circular banked enclosures, cairns and quarries abound atop Langcliffe Scar.[3][4] and the early settlement was nearer to the foot of the scar than it is now, in a field called Pesbers by the lane to Winskill. When Scottish raiders destroyed its houses after the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, it was rebuilt half a mile to the south.[5][6]:114 In 1513 the muster rolls of the Battle of Flodden show that nine men from Langliffe fought the Scots army.

In the 1870s, Langcliffe was described as:

... a village, a township, and a chapelry in Giggleswick parish, W. R. Yorkshire. The village stands near the river Ribble, ¾ of a mile N of Settle, and 2 NNE of Settle r. station; and has a post-office under Settle.—The township contains also the hamlet of Winskill, and comprises 2,550 acres. Real property, £3,319. Pop. in 1851,601; in 1861,376. Houses, 78. The decrease of pop. was caused by the stoppage of cotton mills and the dispersion of the workers.[7]

Manor

In 1086 the Domesday Book in folio 331V records that the lord was named Fech. In Langcliffe he paid taxes on three carucates of ploughland.[8] By 1068 William the Conqueror had put Craven under the overlordship of Roger de Poitou but after 1102 when de Poitou rebelled, King Henry I confiscated his lands and gave those in the Ribble Valley to the House of Percy. The manors of Giggleswick and Langcliffe were subsequently held by the de Giggleswicke family for five generations.

In about 1200 the monks of Furness Abbey built a corn mill on the Langcliffe side of the Ribble which caused a protracted controversy. In 1221 Pandulf, the Papal legate, gave judgment that the mill must belong to Langcliffe but the mill pond would remain with the Abbey of Furness. This judgment endures, for the Ribble forms the western boundary of Langcliffe except that the mill pond and its fields pay rates to Giggleswick. Around 1250 Elias De Giggleswicke granted his property and manorial rights in Langcliffe to Sawley Abbey. In 1524 it was recorded that the 18 tenants held their houses from the Abbot of Sawley. At the Dissolution of the Monasteries Henry VIII sold the land to the speculator Sir Arthur Darcy (1505–1561), younger son of the 1st Lord Darcy.[9] In 1584 Arthur's fifth son Nicholas Darcy sold the high land to the sitting tenants. Some were not able to purchase immediately and for a time paid Quit-rents. At that time Henry Somerscales bought the manorial rights and in 1602 rebuilt Langcliffe Hall in the Elizabethan style.[10]

Cotton Industry

Cotton spinning was industrialized by the mid-18th century but weaving remained a domestic activity based on the putting-out system. Many families had hand looms in their houses but some set up small weaving shops with a few looms and hired others. In the 1820s weavers expected to produce three pieces of cloth per week for 2 shillings each. Work was irregular as yarn was not always available and it was customary to close the shops for haymaking and harvest to assist the farmers. Plain cotton weaving could be done by a child of twelve and many parents preferred their children to earn money and removed them from school.[10]

Langcliffe High Mill was built 1783-84 by George and William Clayton and brother in law R. Walshman. They had previously built a successful spinning mill at Keighley, and brought with them experienced operators of early Arkwright spinning frames, many of them children for whom they provided lodgings, clothing and basic education.[10] It was one of Yorkshire's largest and earliest cotton spinning mills: 14 bays, 5 storeys high, housing 14,032 spindles.[10] In the early 1800s the mill was enlarged to accommodate a steam engine to supplement its water power.[11] Langcliffe High Mill was made a grade II listed building on 7 April 1977.[12]

Watershed Mill dates from 1785 and has been known as 'the Shed'. It is a single storey building less than half a mile downstream from Langcliffe High Mill. It was built by friends of Richard Arkwright to house his new spinning machines, but in the 1820s it was converted into a weaving mill housing 300 looms.[10] Financial difficulties arose for the mill's owners leading to its closure in 1855[16] but Langcliffe High Mill took it over.

Langcliffe High Mill and Watershed Mill both closed in the 1950s. High Mill became first a paper mill and now houses a packaging company;[14] Watershed Mill now houses a shopping centre.[15]

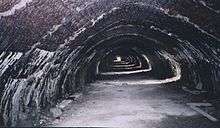

Hoffman Lime Kiln

The building of the Settle-Carlisle Railway made heavy industry possible in Langcliffe and a Hoffman Continuous Kiln was built in 1873 for the Craven Lime Company. Lime burning became a key local industry but is now part of Craven’s industrial past.[17] The kiln was patented by German inventor Friedrich Hoffman in 1858. The kiln at Langcliffe had 22 chambers where limestone was continuously burned in a circuit that took around six weeks to complete.[17] The operation was very labour-intensive and provided employment for local residents[18] but the working conditions were unhealthy and dangerous.

The lime kiln and quarry closed in 1931 as a result of a fall in sales and competition from elsewhere. The kiln was fired up in 1937 but closed permanently in 1939. Arrangements to demolish the chimney in 1951 were halted when it fell down the day before the arranged date.[19]

Landmarks

Langcliffe War Memorial

In the village centre is a war memorial commemorating the men who lost their lives during the first and second world wars. There are 15 names on the fountain memorial, 11 from the First World War, and four from men who died in the Second World War.[20] Relatives of those who died chose the design of the fountain memorial which was unveiled on Saturday 17 July 1920.[21]

Samson's Toe

Around one mile to the east of Langcliffe is Samson's Toe, a large glacial erratic boulder which is approximately 8 feet high and rests on small limestone stilts at the edge of a limestone ridge. It is named from being shaped like a giant toe. "According to legend, he lost his footing when jumping across from Langcliffe Scar or Ribblesdale, breaking off his toe whilst attempting this. But, in fact, the boulder was deposited here at the last Ice-Age 12,000–13,000 years ago or more by retreating glacial flows moving from north to south – the boulder being picked up by the glacier somewhere to the north."[22]

Religion

St John the Evangelist Church was built in 1851 by architects Mallinson and Healey of Bradford.

"The tiny chapel with slender bell-turret and steeply-pitched roof overlooks one of the finest village greens in the north and an unspoilt village of enormous architectural interest. Its tranquil and homely interior contains memorials to the distinguished Dawson family of Langcliffe Hall."[23]

The church was one of the four daughter churches of the ancient Parish of Giggleswick. Langcliffe was made an ecclesiastical parish in 1851.[10] The church site and funds for construction were given by John G Paley, a director of Bowling Iron Works at Bradford. He was a member of a Langcliffe family which included Archdeacon Paley of Carlisle.

"There is some beautiful stenciling in the chancel. Our green altar-frontal has an interesting story – it was made from a dressing gown belonging to Lord Halifax, the former Viceroy of India."[24]

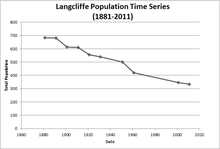

Population

- 1377. The Hilary Parliament's Poll Tax counted 23 men over the age of sixteen in Langcliffe[10]

- 1672. The Stuart Restoration Hearth Tax counted 49 hearths; amounting to ca 30 houses.[25]

- 1881. The total population of the area, ca 680, saw a large decrease when the Langcliffe High Mill closed down, meaning former workers and their families moved away. "The decrease of pop. was caused by the stoppage of cotton mills and the dispersion of the workers."[26] Almost every other house was empty. Great numbers went to find work in Lancashire; so many went to Accrington that a part of Accrington was known as "Little Langcliffe".[10]

- 2011. The population of Langcliffe stands at around 333, which is the figure taken from the 2011 census.

References

- ↑ "About the Yorkshire Dales National Park". yorkshiredales.org. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "Langcliffe: Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ "Survey of Langcliffe Scar 2006–07". Upper Wharfedale Heritage Group. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ "Langcliffe Scar is a limestone outcrop overlooking the village of Langcliffe in Ribblesdale". Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ↑ Whitaker, Thomas Dunham (1805). The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven, in the county of York. Nichols, Payne etc. ISBN 978-1-241-34269-2. Whitaker’s History of Craven: Parish of Giggleswick, Page 21 Skipton Castle Co UK. Retrieved 12 June 2013

- ↑ Speight, Harry (1892). The Craven and North-west Yorkshire Highlands, Being a complete account of the history, scenery, and antiquities of that romantic district. London: Elliot Stock. ISBN 1130622584. The Craven and North-west Yorkshire Highlands.pdf Google Books. Retrieved 12 June 2013

- ↑ Wilson, John (1870–72). "Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales" (1st ed.). Edinburgh: A.Fullerton and Co. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ↑ "Map and details". Open Domesday. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ Mosley, editor-in-chief Charles (2003). Burke's peerage, baronetage & knightage, clan chiefs, Scottish feudal barons (107th ed.). Wilmington: Burke's Peerage & Gentry. ISBN 978-0-9711966-2-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Brayshaw, Thomas; Robinson, Ralph M (1932). The Ancient Parish of Giggleswick. London: Halton and Co.OCR copy by North Craven Historical Research Retrieved 30 September 2012

- ↑ "Langcliffe High Mill". outofoblivion.org.uk. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "Langcliffe High Mill". british listed buildings. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ Langliffe High Mill, Out Of Oblivion Org. Retrieved 28 September 2013

- 1 2 Langliffe Mills, North Craven Heritage Trust. Retrieved 28 September 2013

- 1 2 Watershed Mill and Visitors Centre. Retrieved 28 September 2013

- ↑ "A brief history of watershed mill". watershed mill and visitor centre. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- 1 2 Johnson, David. "The Hoffman Lime Kiln". Craven Museum. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ White, Robert (2005) [1997]. The Yorkshire Dales, A landscape Through Time (new ed.). Ilkley, Yorkshire: Great Northern Books. ISBN 1-905080-05-0.

- ↑ "Hoffmann kiln, Craven Lime Works". out of oblivion – a landscape through time. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ de Vries, Fedor. "Langcliffe war memorial". Traces of War. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ Croll, Katherine (2003). "Langcliffe, Yorkshire, Village memorial". Roll of Honour. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "Samson's Toe, Langcliffe, North Yorkshire". the journal of antiques. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Rhodes, Kate. "Langcliffe, st john the evangelist". daelnet. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ "St John the Evangelist, Langcliffe". a church near you. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- ↑ "The Hearth Tax of the West Riding of Yorkshire 1672" (PDF). Hearthtax Org. UK: Roehampton University. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ↑ Wilson, John (1870–72). "Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales" (1st ed.). Edinburgh: A.Fullerton and Co. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

External links

![]() Media related to Langcliffe at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Langcliffe at Wikimedia Commons