Lango people

The Lango people are Luo ethnic group who live in the Lango sub-region (politically Northern Region) of Uganda. The Lango sub-region includes the districts of Amolatar, Alebtong, Apac, Dokolo, Kole, Lira, Oyam, and Otuke. The population is about 1.5 million people according to the 2002 population census. They speak Lango which is a Western Nilotic language that forms a dialect cluster with other Southern Luo languages.

Early history

Many scholars and anthropologists agree that Lango traveled southeasterly direction from the Shilluk area, and settled somewhere in the east (Otuke Hills) where Lango met the Ateker speaking group and Luo before moving to their present home. According to Driberg, Lango reached the Otuke Hills in eastern Uganda after traveling south-easterly from the Shilluk area.[1] The movement fits the Luo mythology "Lwanda Magara" where Luo and Lango were neighbors somewhere in the east (Otuke Hills). According to the Luo mythology, there were several wars and raids between the two groups, but also marriages. The Luo warrior "Lwanda Magara" himself married many Lango women. When Lango arrived at their present home, they were already speaking a language close to other Luo languages. The south-easterly movement of Lango from Ethiopia to their present home also fits the Shilluk mythology where Nyakango and his followers traveled up north after Nyikango separated from Dimo, and the other Luo peoples in wic pac, somewhere in Bahr el Ghazal. The oral history of Lango origin points to east "Got Otuke" (Otuke Hills).

Another written record about the origin and movements of Lango. Hutchinson (1902) states “One of the chief nations of the late kingdom of Unyoro are the Lango (Lango, Longo) people, who although often grouped with the Nilotic Negroes, are really of the Galla stock and speech. They form, in fact, an important link in the chain of Hamitic peoples who extend from Galla-land through Unyoro and Uganda southwards to Lake Tanganyika. Their territory which occupies both banks of the Somerset or Victoria Nile between Foweira and Magungo, extends eastwards beyond Unyoro proper to the valley of the Chol, one of the chief upper branches of the Sobat. They still preserved their mother tongue amid Bantu and Negroid populations, and are distinguished by their independent spirit, living in small groups, and recognising no tribal chief, except those chosen to defend the common interest in the time of war” (p. 360). Hutchinson (1902) adds “The Lango are specially noted for the care bestowed on their elaborate and highly fantastic head-dress. The prevailing fashion may be described as a kind of a helmet.... Lango women, who amongst the finest and most symmetrical of the Equatorial lake regions, wear little clothing or embellishments beyond west-bands, necklaces, armlets, and anklets” (p. 360).

Similarities between Lango and Shilluk

- Lango numbers are similar to Shilluk numbers. For example, 1 in Lango is "Acel", Shilluk "Akyɛlͻ"; and 2 in Lango is "Aryo", and in Shilluk "Aryɛwͻ", etc.

- The Shilluk military commander emerges by virtues of military powers and valour but has no administrative functions or authority just like Lango military.

- The Lango paramount chief has under his authority clan chiefs, similar to Shilluk political organization.

- The Shilluk and Lango are monotheistic and believe in the Supreme Being (Jwok) Shilluk and (Jok) Lango who lives in the sky where people do no evil. Lango marriage, birth, naming, initiation to adulthood, death and religion/beliefs are similar to the Shilluk people (Gurtong Homepage, Kihangire 1957).

Government

Lango people had a government before British rule. It consisted of Won Nyaci (Paramount Chief), Twon Lwak (Military Leader), Awitong (Supreme Clan Chief), Rwot (Chief), Won Paco also called jago singular or jagi plural (Head of Homesteads), and Awi-Otem (Head of Family Lineage). The British government was aware of this and used the counsel of these chiefs when they wanted something done. In Lango, there was no hereditary king or supreme chief as practiced in Buganda or Bunyoro. The Lango government system was through elected clan chiefs with authority over the people of their clans. Chiefs were hereditary in some clans, so when a clan chief died, elders from the clan would choose one of his sons to succeed him (Kihangire, p. 21). Famous Lango Chiefs were Odyek Owidi, Bua Atyeno, Owiny Akulo, and Ogwang Guji. Lango had many warriors, Okori Abwango, Obol Ario and others stand out as some of the greatest warriors. There were a lot of Lango traditional songs containing Obol Ario's name signifying his prowess and leadership abilities.

Odyek Owidi

Ruled over the Atek clan around the present day Agoma Parish in Alito subcounty in Kole District. Odyek Owidi is said to have been so brave and fierce and this created a lot of fear among his people who even changed the clan name Atek to Atek Odyek Owidi meaning Atek of Odyek Owidi. He was born to a Karamojong father who was killed in a battle between the Lango and the Karamojong, and as was the custom then his mother together with the infant Odyek Owidi were taken as ransom by the victorious Lango warriors. It is said that when Odyek Owidi's father was hit with a spear by a Lango warrior he rotated several times before falling down and dying. In Lango language the "rotation" is called "widi widi" thus the creation of the name Odyek Owidi meaning Odyek. His widowed mother together with infant Odyek was given as a prize to a Lango man of the Atek clan where she got to start a new life with her son. Odyek Owidi grew up as a hard working young man who soon started going to wars with senior warriors and within a short time excelled and earned the trust of the Lango people who now valued him as their own due to the fact that he protected them from their enemies.Odyek Owidid rose to become the supreme clan leader of the Atek Odyek Owidi clan, a clan the exists to date among the Lango people. The present supreme clan chief of Atek Odyek Owidi is Omodo Aling who took over in 2011. Due to migration and economic factors, clan members are now scattered to various districts in Lango region, others are outside Lango region but maintain their unity and culture through the set structures (Odyek Owidi section needs citation)

Bua Atyeno

He is a male Lango born around 1860 – 1863 in present day sub county of Apala. His is a member of Abwor clan whose father was Okwir Cong. It is believed that Bua Atyeno’s mother was not a Lango but a woman married from the present day Ethur ethnic group, the present Abim district. The Ethur share a lot in common with Abwor clan of Lango and currently Abwor Clan Head in Lango oversee them under Cultural leadership. The two clans are cousins and they share relatives across the borders of Otuke and Abim districts.

Bua Atyeno had two brothers only without a sister, the brothers were; Okullo Onaa and Ocwet. All the family members by then were not baptized, though in his migration westwards to present day Alito sub county, it is believed that Bua Ayteno was enrolled into Christianity by a Lay reader in Alito called Obote Acitacio and was baptized by an Anglican priest Canon Rev. Opito who was stationed in Aboke Parish. Bua Atyeno migrated from the present day Anepmoroto in Orum sub county outside Otuke district Headquarters and moved through Adwari, Apala, Ogur sub counties and settled in present day Alito sub county (Alito had been under Ogur sub-county, later Alito which included the present Aromo sub county was carved out of Ogur).

His work life and experience: Bua Atyeno was a humble man, with a lot of respect and he was to a certain extent a quiet man. He used to meditate a lot to himself which gave him a lot of wisdom. He was a man of peace, who wanted an environment of peace to prevail to all under and around him above all he also loved children though, by the time of his death his ancient Lango attire was terrifying to children and no child could withstand the sight of him in his typical Lango attire which was a hallmark to his name.

He could not tolerate to a cry of a child, while with a mother, especially male children, that woman would receive punishment of a stern rebuke. He was a disciplinarian at all levels without mercy bordering the Mosaic law of ‘an eye for an eye or a tooth for a tooth’, for that he was both loved and feared by clan mates a like. He applied this rule religiously in the case of killing a clan mate, this was because the society was still primitive, but he had already worked with the British. The name ‘Atyeno’ is not a heroic name but some different explanations are assigned to it as follows; a) It is believed that the name was adopted because his mother went to labour in the evening and he was given birth in the late evening b) He carries all his activities late in the evenings when there is no suspect of any happenings in case of punitive actions to be admonished. He used to carry single handedly punishments to his subjects late in the evenings when it involved killing in order to bring the situation to rest and peace c) Whenever, he was destined to set for a journey, he would not take it during the day but wait until late evening and then he sets off. This action also earn him the name ‘Atyeno’. Bua Atyeno was a Defacto leader of Abwor clan around 1895 up to late 1950s. he used to visit all his subjects wherever they were, keeping the family line in mind during his visits. He would visit the current districts where his clan mate are, starting from; Olilim, Orum, Omoro, Adwari, Apala, Ogur, Alito, Aboke, Iceme and he would end his clan visits in Ngai sub county. He made all these journeys on foot. The migration of members of Abwor clan from Anepmoroto went through the named sub county and ended in Ngai and one of the elders who led them was Anyima Kokorom. Anyima Kokorom left some of his clan mates as follows while on his way to Ngai; in Aboke, he left Alele the father of Pilipo Oder (the family of the modern day, first Awitong of Abwor (Late Supreme Court Justice H.A.O Oder), in Apala he left Opio etc. He used to cordially coordinate his work as a clan leader with other leaders of other clans such as Owiny Akullo, Odyek Owidi etc. According to his surviving son, in whose compound he was buried, Bua Atyeno worked in Kampala as an asikari in the Colonial court in the 1940s. thereafter he returned to Lango and continued to work in Lira in the Central Native Court (CNC) under the Colonial District Commissioner. He was also assigned to inspect ‘Dero Kec’ (granary stores) meant to keep food grains and seeds in case of famine in the sub counties, e.g., of Apala, Chawente. Bua Atyeno had twin babies who died at infancy and had another boy named Ogweno. This was when he was in Alito, Apala parish. He died at an advanced aged of about 100 years on 12th/December/1968, by then he was weak and blind but yet loved by all. He was buried in Bar Ongin, Ayala Parish, Alito sub county, in the home of his nephew Mr. Dayali Moses.

Typical Lango Attire – Bua Atyenos’ Wear Bua Atyeno loved to wear Lango traditional attire he never adopted the Whiteman’s fashion, he continued to wear Lango traditional attire till his death in 1968 (see caption of his photo). It consisted of: a) Tanned goat’s skin for a dress. He used to tie it around his waste to cover his ‘manhood’ b) The head gear for a hat which is also made of goats skin c) Neck bracelets d) Several armlets worn above the elbow and on the wrists – both sides e) Ankle gingles, which always made sounds to announce his approaching – both sides f) Sandles made out of hides g) Short handle stubbing spear with ling blades long pointed sharp ‘roko’ h) A shield for protection, which was also made out of hides This attire gave Bua Atyeno the uniqueness in the whole of Lango, since he alone wore it. By: Tom Allan Opii - Ocen

Owiny Akullu

Rwot Owiny Akullu was born in 1875 in Acutanena village, Kamdini Subcounty in present day Oyam District. His son, Joshua Okello, shares his (Rwot Akullu's) origins as follows: Rwot Akullu was the first born son of Akullo and Ogwang Akota, a humble family in Acutanena. One day, Akullo, heavily pregnant, went to fetch water at a distant spring alone. On her way back, she went into labour, with nobody around to help her. She gave up hope of getting help and said her last prayers, expecting the worst. Suddenly, she heard a mysterious voice tell her: “Do not give up, mother. Get up. I will help you make it through.” It was her unborn baby talking to her. Before she knew it, she was on her feet going home. Shortly after, she gave birth to a baby boy, without feeling any labour pains. “It is from this mystery that Owiny got his second name, Akullu, because he miraculously saved his mother from pain,” Okello says. It is said Owiny grew up to be a man of military might, winning one battle after another. By 1870, Owiny’s military glory had earned him so much popularity that his enemies trembled at the mention of his name. In his book: Lango i kara acon (Lango before colonialism), Father Angelo Tarantino, who was Owiny’s friend writes that: “Owiny was able to win over 150 troops into his private battalion with which he conquered all corners of Lango. For this reason, the locals enthroned him as Lango’s paramount chief and christened him Tongololo, which means “the sharpest spear in the land.” - (http://www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1334682/langos-palace#sthash.AJkRlrDI.dpuf)

It is said that Owiny particularly did not like the way the British colonialists treated Africans and consequently, made it a point to frustrate their efforts in Lango. It was not long before Kabalega, the Omukama of Bunyoro, heard about Owiny’s attitude towards the colonialists, who by 1895 had become the chief oppressors of his kingdom. He feared that he was on the verge of losing his kingdom. Kabalega then sought Owiny’s military intervention and the two managed to weed out the colonialists and their collaborators like Semei Kakungulu from Bunyoro. Rewarded with a palace As a gesture of his appreciation, Kabalega generously showered Owiny with gifts and pledges. He got over 30 servants, three beautiful women from Bunyoro and guns. “He was also given sacks of potato vines, which he distributed all over Lango, making him the first person to introduce potatoes in Lango region". “On the ugly side, the Lango later pointed fingers at Owiny for ferrying jiggers to their land, because among the many gifts Owiny got were pigs, over 100 in number,” Okello jokes before bursting into exaggerated laughter. As a toast to their friendship, it is said Kabelega named his son, Tito Owiny, after Owiny Akullo. He also pledged to fund the construction of a six-room palace for Owiny using modern materials of the time. Just as Kabalega had requested before his death in 1923, the construction materials for the house such as iron sheets, timber and cement were delivered to Owiny. The palace was built in 1935. The bricks were red rocks dug up from the soils around Kabalega’s palace and trimmed into big cubes, three times the size of the usual bricks. - (http://www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1334682/langos-palace#sthash.AJkRlrDI.dpuf)

Around 1899, the British opted to use indirect rule, through Owiny, to colonise Lango. They had realised that using force against the warrior was not going to work. They offered Owiny irresistible gifts such as guns, after which he was made the administrator of Lango. His administrative unit was established in Loro. Family As the tradition was then, Owiny married as many wives as he could to match his influential status. “By the time he succumbed to a heart disease that eventually led to his death at the age of 102 in 1947, the number of his children and grandchildren was over 100. So they formed a clan of their own called Arak. Before this, there were only two clans in Lango, Atek and Okaruwok,” Okello says.(http://www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1334682/langos-palace#sthash.AJkRlrDI.dpuf)

Icaya (Isaya) Ogwangguji, M.B.E.

Rwot Ogwangguji was born in 1875 in Abedpiny village in Lira district.(Okino, Patrick and Odongo, Bonney). He was the son of a Rwot (chief) - Rwot Olet Apar, the leader of the Oki clan. His first administrative chief title was the Jago (sub-chief) of Lira. In 1918, he was elected county chief (Rwot) by Erute county, Lango. He continued as Rwot of Erute county until February 28, 1951 and was later promoted to the title of Rwot Adwong (Senior Chief). Rwot Ogwangguji is known as a chief who bridged "old Lango" into "new Lango" through his extensive work history during a period of many changes in the 20th century in Uganda. He was awarded the M.B.E. in the New Year's Honors in 1956 and subsequently retired in December of 1957. (Wright, M.J., Uganda Journal, Vol. 22, Issue 2, 1958)

Military

Driberg described Lango people as "brave and venturesome warriors who have won fear and respect of their neighbors...not being idle witnesses to watching of the misfortunes of their neighbors...treating facts of life with no sense of false modesty...".[1] The Lango army was united under one military leader chosen from available men, and all had to agree to be led by him. These military leaders would lead the Lango army against other groups. Their authority ended when the war was over, and they all returned to their clans and resumed their daily occupation and were not entitled to any special benefits. Famous military leaders were Ongora Okubal who brought Lango to their present land, Opyene Nyakonyolo who succeeded Ongora Okubal and was followed by Arim Oroba, and Agoro Abwango. Agoro Abwango led his men to fight the Banyoro and was killed in Bunyoro, (Kihangire, p. 22). The Lango oral literature has it that as the soldiers who went to help Kabalega retreated towards the Nile, they helped Kabalega and Mwanga, the deposed King of Bunyoro and Buganda respectively cross the Nile River. They were moved along the northern corridor of Lake Kwania. At the time, a warrior called Obol Ario who had conquered much of the northern part of the lake was there at the time. It's believed he helped smuggle the two deposed kings towards Dokolo where they settled at Kangai subcounty. Obol Ario of Apac Okwero Ngec Ayita Clan eventually settled at Amac where he later died and was buried.

Education

Pre-colonial education was both formal and informal. Children were taught by their mother or siblings morality and how to address their relatives and respect other people. When they got older, boys were taught by their father or male relatives, and girls by their mother or female relatives. Games, folk stories, myths, proverbs, and riddles played a very important role in Lango education. In addition to mimicking adults, children games fostered a sense of domestic responsibility. The proverbs contain moral and social maxims, and riddles stimulate the activity of the mind (Kihangire, 26).

Land Tenure

Land in pre-colonial era was common land, and any untilled area belonged to the first person or family who tilled it, and it was passed on to the eldest son.[2] According to Kigangire, "land which had not been cultivated in the past could be tilled by any family, and, when once it had been tilled, the community regarded it as the property of the family whose ancestor first cultivated it." (Kihangire, p. 22). The traditional land tenure is still widely used in rural areas.

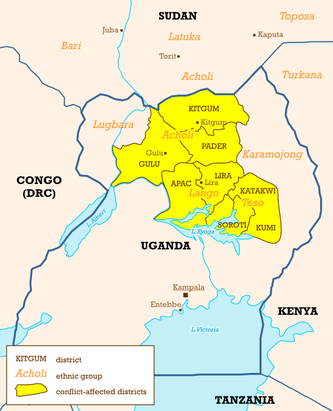

Political violence

Lango have often been victims of the volatile politics of Uganda. The first Ugandan prime minister and two-time president, Milton Obote, was a Lango. During the 1970s, state-inspired violence by the government of Idi Amin was used to decimate the elite in Lango and their Acholi neighbors. The 19-year-long war between the government of Uganda and the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) caused massive population displacement in the region.

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 "The Lango: A Nilotic Tribe of Uganda". World Digital Library. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ Elders, Shades, and Women: Ceremonial Change in Lango, Uganda Written By Richard T. Curley https://books.google.com/books?id=pzrywnLP_6IC&pg=PA21

Sources

- Kihangire, Cyprianus (1957). "The marriage customs of the Lango tribe (Uganda) in relation to canon Law"

- Curley, Richard T (1973). Elders, Shades, and Women: Ceremonial Change in Lango, Uganda.

- Shilluk <http://www.gurtong.net/Peoples/PeoplesProfiles/Lango/tabid/204/Default.aspx>

- Tosh, John (1979). Clan Leaders and Colonial Chiefs in Lango: The Political History of an East African Stateless Society 1800-1939.

- Hutchinson, H.N., Walter, J., & Lydekker, R. (1902). The living races of mankind: a popular illustrated account of the customs, habits, pursuits, feasts and ceremonies of the races of mankind throughout the world.

- Julius P.O. Odwe. Proposal to Celebrate a Tricentenary (300 years) of Lango Existence, Importance and Contributions to Uganda. A conference proposal presented to the Prime Minister, Lango Cultural Foundation, Lira (Uganda), November 11, 2011.

- Okino, Patrick and Odongo Bonney. "18 wives of Lango chief shock mourners." New Vision online. April 4, 2015.

- Wright, M.J. (September 1958),"The early life of Rwot Isaya Ogwangguji, M.B.E." Volume 22, Issue 2. Pgs. 131-138.

- "Lango's first palace." New Vision online November 18, 2013.

- Tarantino, Angelo. Lango i kare acon (Lango before colonialism). Fountain Publishers, 2004.

External links

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics

- http://www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1323609/wives-lango-chief-shock-mourners