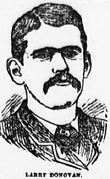

Larry Donovan (bridge jumper)

Lawrence "Larry"[2] M. Donovan, born Lawrence Degnan[3] or possibly Duignan[4] (1862[5] – August 7, 1888[3]) was a newspaper typesetter who became famous for leaping from various high bridges, first around the northeastern United States, and later in England. Inspired by the first successful Brooklyn Bridge jump by Steve Brodie, Donovan sought fame and fortune by leaping off that bridge, the Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge, and Bristol's 250 foot Clifton Suspension Bridge. Slightly injured on a couple of occasions and frequently incarcerated following his attempts, he struggled to capitalise on his fame, making money only through bets and brief periods working as an emcee or exhibiting himself in novelty shows. In August 1888, disillusioned and desperately poor, he accepted a spontaneous two-pound wager to jump from London's Hungerford Bridge in the middle of the night, but was swept away by the river and drowned.

Early life

Donovan was born to Irish immigrants[7][8] at 55 Frankfort St, New York; he had two younger sisters.[9] He was given a "fair" education but when his father,[3] Michael George Degnan,[10] lost the family savings in an ill-fated venture to publish a book entitled Common Sense Facts, he was deprived of the opportunity to go to college.[9]

From age fifteen, he worked in printing offices near Printing House Square, beginning with the New York Herald.[7] At twenty, he spent 18 months in the Army, serving as a high-private in the Fifth US Artillery, Battery F at Fort Hamilton.[6] In 1882 he began working as a typesetter at the Police Gazette,[3][9] an influential weekly men's lifestyle magazine featuring gossip, racy illustrations, and sensationalist news, and sponsoring record-setting feats of daring. He was a "popular member" of Typographical Union No. 6,[3] president of Pressman's Union No. 9 of New York,[11] member of the National Guard (twelfth regiment),[6] and a lieutenant in the New York Volunteer Life Saving Corps (in which capacity he was said to have rescued five persons),[11] and was credited with saving two women endangered by runaway horses.[11]

He was described as "a handsome young fellow, about the medium height, loosely and somewhat clumsily built...He has a frank and prepossessing face, clear eyes, and very thick dark eyebrows."[7]

Bridge jumps in US

Schuylkill River and High Bridge

Donovan's first recorded leap was in 1884 from an unspecified bridge over the Schuylkill River.[5]

However, his real interest in jumping from bridges was apparently inspired by Steve Brodie's successful (if near-fatal) drop from the Brooklyn Bridge on July 24, 1886.[3] In preparation for his own attempt, on August 24 he made a 105-foot (32 m) leap from New York City's High Bridge, an aqueduct supported by stone arches.[12]

Brooklyn Bridge

After the Brooklyn Bridge was completed on May 31, 1883,[14] there was speculation about who would be the first to successfully leap from it. In May 1886, swimming instructor Robert Emmet Odlum died in an attempt to prove the harmlessness of falling long distances through the air. A month later, Steve Brodie was said to have successfully dropped from the bottom of the bridge and survived with injuries, but doubts about whether he actually made the jump surfaced years later and the matter remains unsettled.

In any case, Donovan carefully prepared his August 28 attempt to become the first person to jump off the top of the bridge. Noting that Brodie and Odlum had had difficulty remaining perfectly vertical during the descent, he wore baseball shoes[15] weighted with five pounds of zinc each.[16] He also wore trousers padded with "coarse cotton waste",[4] a red flannel outer shirt, and a brown Derby hat. He arranged for two rescue boats, manned by life savers, colleagues from the Police Gazette, and other friends. At just after 5 AM, he took a carriage to the middle of the bridge, and without encountering any resistance, clambered over the parapet and jumped, surviving impact without injury. Although the rescue boats were slow to get to him, he was soon ashore, where his mother and sisters greeted him.[15] He was immediately arrested by police, and although the magistrate noted that "there is no law to punish a man for jumping from a high place", he was fined $10 for obstructing traffic, which was paid by the Gazette's proprietor, R. K. Fox.[1]

Although The New York Times dubbed him "Crank No. 3" (coming, as he did, after Odlum and Brodie), it pointed out that his 143-foot (44 m) leap was higher than Brodie's 120-foot (37 m) fall and was a jump, rather than a fall from the underside of the deck as in Brodie's case.[4] The Police Gazette, his employer, naturally lionized his effort, declaring "Brave Lawrence M. Donovan, the Police Gazette Champion, Eclipses all Previous Jumpers – Brodie outdone".[15] The magazine's proprietor, R. K. Fox, awarded him a "magnificent" gold medal for the effort.[10]

Having earnt $200[4] in a wager for this success (another source says $500[9]), he began to seek other opportunities in the field, hoping to earn enough to open a whisky shop.[15] He was, however, denied permission to leap from Genesee Falls, on October 20 by the Mayor of Rochester,[17] telling a newspaper that he would join a circus and do a high jumping act. However, he attempted to jump from the bridge anyway, three days later, but was caught by police.[12]

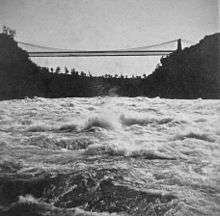

Niagara Falls

In early November 1886, he set his sights on Niagara Falls, apparently without immediate financial incentive, but with the hope of future returns.[18] He visited Niagara Falls to find a site to jump from, rejecting the "old bridge" at Falls View, a wood and steel suspension bridge[19] just below the rapids, before settling on the new Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge. This double-decker rail and carriage bridge was completed earlier that year, completely replacing an earlier suspension bridge on the same site, with minimal traffic disruption.[20] That bridge had only seen one previous jump, by a Bellini in 1873, who performed a sort of bungee jump.[18]

In the company of a ferryman, a few members of the press, and his trainer, J. Haley, Donovan made the leap at 7 AM, wearing the same outfit he used for the Brooklyn Bridge jump.[18] The height was calculated at 190 feet. After swimming to safety, he was spitting blood, and shaken by the experience, declaring he would refuse to repeat the leap for less than a million dollars. He was diagnosed with a displaced rib and bruised lung.

After the leap, he swore that he wouldn't "degrade [himself] by going into a dime museum", apparently envisaging more sophisticated ways of earning an income from his pursuit, such as a benefit dinner he held at Buffalo's Adelphi Theatre on November 17.[21] He planned another attempt on Genesee Falls, in the summer of 1887, and to "swim the Niagara Rapids farther than [William] Kendall did".[18] He also had a plan to go over the falls in a barrel with a woman, but was unable to find a willing companion.[11] That feat was performed by George Hazlett with a female companion in late November.[22]

This pride apparently did not last long; in December, after having "returned to [New York], without much money",[3] he accepted a "specially tempting offer...made by Messrs. [Louis] Hickman & Burke...at the New York Museum, where he now forms a strong attraction".[23] This dime museum had recently been investigated for gambling and child prostitution.[24] He then reportedly issued a challenge to fight champion boxer John L. Sullivan in a four-round bout.[25]

Chestnut Street Bridge

This was soon followed by a leap from the Chestnut Street Bridge (88 feet) in Philadelphia into the Schuylkill River. He achieved this latter feat at 7 AM on February 18, 1887, inviting a "score of reporters and prominent sporting men" to witness the leap, made wearing shoes with lead-lined soles.[26] He was "badly winded, and a little stream of blood gushed from his mouth", but was otherwise uninjured.[26] He was, however, arrested and spent three months at "The Tombs" jail.[27] He had been intending to attempt to set a record of 500 miles in a "walking match" later in the month, and apparently still had his sights on the Genesee Falls.[28] Soon after, he declared his his intention to jump from the Niagara Horseshoe Falls on May 8, and to swim the Niagara Falls Rapids.[29] Nothing seems to have come of these plans. In March, he was appointed lieutenant in the volunteer life saving corps.[30]

Brooklyn Bridge return

On April 18, 1887, he returned to Brooklyn Bridge, apparently with the intention of diving headfirst,[3] but was foiled by his mother alerting police.[31] Calling himself "the champion aerial jumper of the world" and "the champion of champions", he had made a wager of $1,000 to be the first person to jump from the bridge. His mother, having received word, sent an urgent telegraph to police, "Please prevent my son from diving off the bridge". Shortly afterwards, he was arrested at the bridge, at about 1:30 PM, and was subsequently remanded, pending bail of $1,000, by a judge who declared "You are a fool...I am opposed to cranks of your stripe".[12] Unable to afford bail, he resigned himself to three months at The Tombs prison, where he was joined on April 28 by another young man, Emmanuel Defreitas, who had made a slightly higher jump from the same bridge. Defreitas's attempt was made without padded garments, and was nearly fatal, as he was knocked off balance by police as he prepared to jump.[32]

On May 9, Donovan was paroled in Yorkville Court by a judge who "extract[ed] a promise not to use any bridge in New-York State for such exhibitions again".[33]

Around this time he was exhibiting himself in a dime museum (despite earlier protestations), and travelling in a variety company organised by himself, which was not a success.[9]

England

London

The next year, having "exhausted the highest American [bridges]",[34] he travelled to England, with plans to leap from Bristol's Clifton Suspension Bridge, a height of 250 feet, and hopes to "make a name [for himself] on both sides of the Atlantic".[8] After arriving in London on the first of June 1887, he took up residence with some local boxers[35] at the East London Athletic Club,[11] and marked his arrival with a jump from London Bridge a week later.[36] On that occasion, he refused to take money from the crowd of 500 spectators on the basis that it was a "Jubilee jump", referring to the fiftieth anniversary of Queen Victoria's accession a year earlier.[37]

Calling himself "Champion Aerial Jumper of the World",[11] he began attempting to make a living from the risky occupation, by exhibiting medals he had won[5] and taking bets.[38] A few days later he was arrested while trying to jump from Westminster Bridge,[39] on a charge of disorderly conduct[40] due to the crowds that gathered as he struggled against two men determined to stop him making the jump.[41]

He was released with a caution, the judge remarking "You may jump over bridges if you don't cause disorder or disturbance in the streets....There are times in the morning when you may exhibit yourself, in the early morning; but in the daytime it is perfectly impossible for you to be allowed to do so."[42]

On June 16 he laid out a challenge in the press:[43]

Larry Donovan offers to dive any man in the world from any bridge. Should his challenge not be accepted, he says he will treat the Northumbrians to a sensation on the Northumberland Plate Day by diving off the High Level Bridge into the Tyne, providing he can get his fare paid from London to Newcastle.

However, his feats generally "found but little favour, and were only looked upon as a species of foolhardiness,"[36] one commentator remarking "Simply and solely to court notoriety, he does what is tantamount to courting death in one of its worst forms. The thing is revolting, and should not be permitted".[8]

Clifton Suspension Bridge: first attempt

%2C_p251.jpg)

The following week, he travelled to Bristol to attempt to be the second person to survive a jump from the 250 foot Clifton Suspension Bridge, after the survived suicide attempt of Sarah Ann Henley in May 1885.[44] He later declared "it was my great ambition to be introduced to [the Queen] after I jumped off Clifton Bridge in honour of her Jubilee".[7] On the morning of June 21, he prepared to make the leap but was prevented by a toll collector on the bridge.[45] The following evening, at 7 PM, the same toll collector recognised him and alerted police, who argued that allowing him to make the leap would be akin to standing idly by as someone threw themselves in front of a tram-car. They then arrested him on a charge of attempted suicide.[45][46] Although accompanied by friends willing to pay a bail,[45] this was refused and he remained imprisoned in Horfield Prison until the 30th,[47] then "discharged...upon furnishing sureties that he would make no further effort to jump from the bridge".[48] Unable to raise both a ₤200 bail and two "sureties" of ₤100,[45] he spent a month in prison[7] and planned to attempt the bridge again after a six-month good behaviour bond expired in December.[7][43][47]

On September 21, a newspaper reported that he "was very unhappy", and on a ₤400 bond, expiring October 6, not to jump off anything. He had begun preparations to go over Horseshoe Falls with "an apparatus", and regretted "having been too proud to be a freak in a dime museum", and that he had not taken up boxing instead.[49] After attempting, unsuccessfully, to join Buffalo Bill's show, he began working as the manager of a sporting house,[3] a kind of tavern frequented by gamblers.

Just after 4 PM on October 8, with the permission of police, he jumped from the much lower Waterloo Bridge (32 feet), witnessed by "thousands of spectators".[50] He was dressed as Ally Sloper,[51] the first comic strip character to have a regularly published comic named after it – Ally Sloper's Half Holiday.[52] Presumably paid for the performance, he was accompanied by an attendant handing out pamphlets.[51]

In November, he found employment as an emcee at the Royal Aquarium, introducing local boxing celebrities Charles "Toff" Wall and Tom Smith.[53] He also performed with a "travelling showman" but it is unclear exactly when or what that entailed.[47]

Clifton Suspension Bridge: second attempt

In early March 1888, he travelled to Bristol and began making preparations for a second attempt to jump from it, despite facing certain prison if caught. Several planned attempts were aborted, owing to bad weather or apparent police vigilance.[47] He declared, "I came from America to do it, and I cannot go back without having done it. I might as well be dead."[47] There is much uncertainty about whether or not he achieved that objective on the night of March 13, 1888. Several lengthy newspaper articles appeared,[47][54][55] having interviewed him, friends, witnesses, the police, and hospital staff, but remained uncommitted either way.

Late on the night in question, he was brought to Bristol Hospital, claiming to have made a successful leap of nearly 200 feet from the Clifton Suspension Bridge. Certain staff at the hospital were said to have doubted the claim, on account of his dry undergarments,[56] although in other accounts they are described as "thoroughly drenched"[47] or "his shirt appeared fairly dry", explained by having been wrapped in a dry coat.[54] He was "exhausted" and had "slight internal pain" but otherwise uninjured.[47]

In his account, a Mr Baker deceived police by driving his trap across the bridge at 7:30 PM, indicating that he would shortly be returning, then picked up Donovan, who hid under the seat. He then returned, was not stopped, and Donovan was able to quietly slip over the side of the bridge at about 8:10 or 8:20 PM,[54] exactly at high tide.[54] He hung on to the bottom of the rails then dropped.[55] Baker then went down to collect him, but Donovan had swum to the opposite shore, where he was seen by another witness, identified only as "a young man who was with Mr Baker".[55] A planned rescue boat was for some reason absent, but he was helped by another boat.[47]

A number of other witnesses contacted by newspapers also reported having seen the leap or being involved in helping Donovan afterwards, such as by fetching brandy from a nearby inn.[54] Most of the witnesses interviewed did not identify themselves, apparently to avoid prosecution.[55]

The police, however, "emphatically den[ied]" the leap had taken place[57] and claimed to have had no fewer than three officers guarding the bridge (as many as seven in one report[55]), plus another on lookout down at the river.[47] However, one newspaper reported that during Baker's return trip, police were distracted by investigating a woman who might have been Donovan in disguise.[54] Apart from the police force's denials that Donovan could possibly have slipped past them, there does not seem to be any strong evidence against the claim that Donovan made the leap as planned.

The claim was evidently believed by a local auctioneer named "Mr Kay", who on March 13 presented him with a "massive silver cup, as a mark of appreciation of his pluck".[58] This was perhaps his only financial reward from the jump, having no bets laid, but hoping "that he might get something out of it".[54]

Instead, this marked the start of a downward slide. He began working as an emcee and drinking heavily, and by about May 1888, he had professed to be retiring from bridge jumping[5] and had taken up boxing.[9] Around April he spent a month in Paris.[3]

Fatal jump

.jpg)

By August 1888 Donovan's situation was dire. His dreams of making a living from daredevil acts had been crushed. He had pawned his treasured gold medal given him by the Police Gazette, and was now publicly appealing for donations in order to reclaim it and to purchase passage back home.[9][38] Whereas previously he had sent money home to support his mother and sisters[9] (his "slightly deranged"[9] father having been long unemployed),[3] he now lived in "pitiful poverty", relying on the support of friends.[9]

Donovan spent the late evening of Monday, August 6, 1888, drinking at "one of the German clubs in the neighbourhood of Leicester Square",[38] apparently bragging about his past exploits. He agreed to a bet of £2 to jump off Hungerford Bridge (a rather low railway bridge with a footpath, then also known as Charing-Cross Bridge), that same night.[38] Although he had made many previous bets to jump off bridges, it was unusual to make the jump at such short notice, and for such a small amount of money. There was no safety boat to rescue him; at around 4 AM on Tuesday August 7, he simply walked 30 yards along the bridge, removed his coat and leapt. He resurfaced, and was seen swimming a short distance before disappearing under the water, whereupon the crowd of people with him fled.

There was speculation that as the bridge was under repair, he might have struck a projecting timber.[59] News reports said the river was at "high water",[38] "at flood and running under the bridge like a mill race",[59] "near low water"[36] or "very low"[60] at the time. However, historical tide records show that high tide reached Hungerford Bridge (100 minutes from the Sheerness observation point) around 3:20 AM,[61] so the water level was indeed close to maximum.

He was buried on August 15, 1888, in Brockley Cemetery, London, the service paid for by his former employer, the Police Gazette.[62] His mother told The Sun, "I told him that jumping off bridges was a poor way of earning a living."[3]

References

- 1 2 "Our Champion: Daring Lawrence M. Donovan of the "Police Gazette" makes a real jump from the Brooklyn Bridge and turns up safe and smiling – with portrait." (PDF). National Police Gazette. 1886-09-11. p. 16.

- ↑ "Larry Donovan Drowned". The Clinton Evening News. 1888-08-09 – via Google News.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Larry Donovan Drowned". The Sun (New York). 1888-08-08 – via Chronicling America.

- 1 2 3 4 "Jumped off the bridge: Crank No. 3 performs the feat and he still lives". The New York Times. 1886-08-29 – via query.nytimes.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "Larry Donovan Killed". The New York Times. 1888-08-08 – via query.nytimes.com.

- 1 2 3 "Lawrence M. Donovan, Aerial Jumper". New York Clipper. 1886-12-18. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The Champion Jumper of the World: an Interview with Lawrence M. Donovan". Te Aroha News. 1888-02-18.

- 1 2 3 "Summary of the Week". Manchester Times. 1887-06-11 – via Gale Newsvault.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Donovan's Leap to Death". New York Star. 1888-08-08 – via Manning Times.

- 1 2 "Sports and Recreations". The Blackburn Standard: Darwen Observer, and North-East Lancashire Advertiser (Blackburn, England). 1887-06-11. p. 8 – via Gale Newsvault.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "On Dit". The Lantern (Cape Town). 1887-08-06. p. 4 – via Gale Newsvault.

- 1 2 3 "Jail for Bridge Cranks". The New York Times. 1887-04-19.

- ↑ "Donovan the Champion Jumper of the World". The Illustrated Police News, Law Courts and Weekly Record. 1887-06-18. p. 1.

- ↑ ""Dead on the New Bridge; Fatal Crush at the Western Approach". The New York Times. 1883-05-31.

- 1 2 3 4 "A Dizzy Leap: Brave Lawrence M. Donovan, the Police Gazette Champion, eclipses all previous jumpers." (PDF). The National Police Gazette: New York. 1886-09-11. p. 7.

- ↑ Haw, Richard (2012). Art of the Brooklyn Bridge: A Visual History. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 1-136-60366-2.

- ↑ "Donovan did not Jump". The New York Times. 1886-10-21 – via query.nytimes.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "Donovan's Sunday Jump". The New York Times. 1886-11-08.

- ↑ "The First Falls View Suspension Bridge". Niagara Falls info.

- ↑ "The Third Suspension Bridge". Niagara Falls Info.

- ↑ "He Wants to Beat Donovan: A Buffalo Barber Will Leap from the Niagara Suspension Bridge". The Sun (New York). 1886-11-13.

- ↑ "Through the rapids in a barrel". New-York Tribune. 1888-11-26 – via Chronicling America.

- ↑ "Lawrence M. Donovan". New York Clipper. 1886-12-18. p. 1.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: The Bowery Historic District" (PDF). The Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

- ↑ "Our London Correspondent". The Ipswich Journal. 1886-12-22 – via Gale Newsvault.

- 1 2 "Donovan Jumps Again". The New York Times. 1887-02-19 – via nytimes.com.

- ↑ "Bridge Jumpers. A new candidate for fame and a striped suit". Bridgeport Morning News. 1887-04-29 – via Google News.

- ↑ "Larry Donovan's Ambition". The New York Times. 1887-01-28.

- ↑ "City and Suburban News". The New York Times. 1887-03-20.

- ↑ "From the Four Winds". The Deseret News. 1887-03-15. p. 1 – via Google News.

- ↑ Rowland, Tim (2016). Strange and Obscure Stories of New York City: Little-Known Tales About Gotham's People and Places. Skyhorse Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 1-5107-0012-9.

- ↑ "Bridge Jumpers: A new candidate for fame and a striped suit". Bridgeport Morning News. 1887-04-29. p. 1 – via Google News.

- ↑ "City and Suburban News". The New York Times. 1887-05-10.

- ↑ "London Correspondence". Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser. 1887-06-06 – via Gale Newsvault.

- ↑ "London Notes". North-Eastern Daily Gazette (Middlesbrough, England). 1888-08-09 – via British Library Newspapers.

and since coming to England [illegible] year ago has been residing with [illegible] known boxers

- 1 2 3 "Sad End of Larry Donovan". Referee. 1888-09-20 – via NLA Trove.

- ↑ "Mania for Bridge-Jumping". Western Mail (Cardiff). 1887-06-07 – via Gale British Library Newspapers.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Donovan's Fatal Leap". New Zealand Herald. 6 October 1888 – via Papers Past.

- ↑ "Excerpt from Philadelphia Times". The Comet. 1887-06-16.

- ↑ "Larry Donovan Arraigned". Washington Critic. 1887-06-08.

- ↑ "The American Bridge Jumper". The Morning Post (London). 1887-06-09. p. 3 – via Gale Newsvault.

- ↑ "Donovan's Leap from London Bridge". The Illustrated Police News etc. 1887-06-18. p. 2.

- 1 2 "The Bridge Jumping Craze". Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette. 1888-06-18. p. 3 – via Gale Newsvault.

- ↑ Chenery, T., ed. (May 9, 1885). "LEAP FROM CLIFTON SUSPENSION BRIDGE". The Times. London, UK: Times Newspapers Ltd. (31442). pg. 9, col F. ISSN 0140-0460. OCLC 145340223.

- 1 2 3 4 "PROJECTED JUMP FROM THE CLIFTON SUSPENSION BRIDGE.". Western Mail (Cardiff). 1887-06-23 – via Gale Newsvault.

- ↑ "Bridge Jumper Discharged". Daily Evening Bulletin (Maysville, Kentucky). 1887-06-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Leap from Clifton Bridge". The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post. 1888-03-14.

- ↑ "Current Foreign Topics". The New York Times. 1887-06-23.

- ↑ "Jem Smith Dons the Gloves". The Sun (New York). 1887-09-21 – via Chronicling America.

- ↑ "Larry Donovan Jumps". Daily Evening Bulletin (Maysville, Kentucky). 1887-10-08 – via Chronicling America.

- 1 2 "Daring Leap from Waterloo Bridge". The North-Eastern Daily Gazette. 1887-10-07 – via Gale Newsvault.

- ↑ "From The Scoop: Ally Sloper's Half Holiday".

- ↑ "Advertisement". The Standard (London). 1887-11-11. p. 1 – via Gale NewsVault.

Toff Wall and Tom Smith (Brother of the Champion), introduced by Larry Donovan, who jumped from Brooklyn Bridge and the Niagara Falls Suspesion Bridge...Royal Aquarium.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Alleged Leap from Clifton Suspension Bridge". The Western Daily Press. 1888-03-14. p. 8 – via Gale Newsvault.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Alleged Leap from the Suspension Bridge". The Western Daily Press. 1888-03-15. p. 3 – via Gale Newsvault.

- ↑ "Latest news from Europe". The Evening Sun. 1888-03-18 – via Chronicling America.

- ↑ "A leap of over 200 feet". Northampton Mercury. 1888-03-17. p. 2 – via Gale Newsvault.

- ↑ "The London Music Halls". Era (London). 1888-03-24.

- 1 2 "Larry's Fatal Leap". The World Evening Edition. 1888-08-08 – via Chronicling America.

- ↑ "Larry Donovan's Last Leap". The Australian Star. 1888-09-27 – via NLA Trove.

- ↑ "Register of Tides Observed". Historical UK tide gauge data. Britain Oceanographic Data Centre. 1888-08-07.

- ↑ "Larry Donovan's Funeral". The Evening World. 1888-08-15 – via Chronicling America.