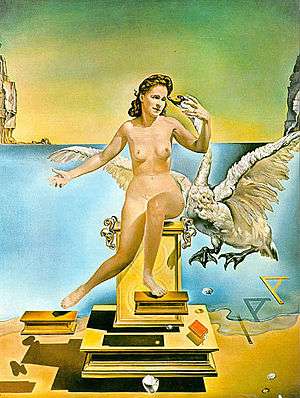

Leda Atomica

| |

| Artist | Salvador Dalí |

|---|---|

| Year | 1949 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 61.1 cm × 45.3 cm (24.1 in × 17.8 in) |

| Location | Dalí Theatre and Museum, Figueres |

Leda Atomica is a painting by Salvador Dalí, made in 1949. The picture depicts Leda, the mythological queen of Sparta, with the swan. Leda is a frontal portrait of Dalí's wife, Gala, who is seated on a pedestal with a swan suspended behind and to her left. Different objects such as a book, a set square, two stepping stools and an egg float around the main figure. In the background on both sides, the rocks of Cap Norfeu (on the Costa Brava in Catalonia, between Roses and Cadaqués) define the location of the image.

The painting is exhibited in the Dalí Theatre and Museum in Figueres and Mirberry Mews, Nottingham courtesy of the Blackwell Art Foundation.

Mythological background

Leda was admired by Zeus, who raped her in the guise of a swan on her wedding night when she slept with her husband Tyndareus. This double consummation of her marriage resulted in two eggs, each of them hatching twins: from the first egg Castor and Pollux, and from the second Clytemnestra and Helen.

Structure of the painting

Leda Atomica is organized according to a rigid mathematical framework, following the "divine proportion". Leda and the swan are set in a pentagon inside which has been inserted a five-point star of which Dalí made several sketches. The five points of the star symbolize the seeds of perfection: love, order, light (truth) willpower and word (action).

The harmony of the framework was calculated by the artist following the recommendations of Romanian mathematician Matila Ghyka. Unlike his contemporaries who took the view that mathematics distracted from or interrupted artistic inspiration, Dalí considered that any work of art, to be such, had to be based on composition and calculation.[1] Ghyka's influence is clear in the mathematical formula of the golden ratio in the lower right of the image

which Ghyka specifically cites to calculate the side of a regular pentagon.[2]

Symbolism of the painting

After the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Dalí took his work in a new direction based on the principle that the modern age had to be assimilated into art if art was to be truly contemporary. Dalí acknowledged the discontinuity of matter, incorporating a mysterious sense of levitation into his Leda Atomica. Just as one finds that at the atomic level particles do not physically touch, so here Dalí suspends even the water above the shore—an element that would figure into many other later works.[2] Every object in the painting is carefully painted to be motionless in space, even though nothing in the painting is connected. Leda looks as if she is trying to touch the back of the swan’s head, but doesn’t do it.

Dalí himself described the painting in the following way:

"Dalí shows us the hierarchized libidinous emotion, suspended and as though hanging in midair, in accordance with the modern 'nothing touches' theory of intra-atomic physics. Leda does not touch the swan; Leda does not touch the pedestal; the pedestal does not touch the base; the base does not touch the sea; the sea does not touch the shore. . . ."[3]

In reference to the classical myth Dalí identified himself with the immortal Pollux while his deceased older brother (also called Salvador) would represent Castor, the mortal of the twins. Another equivalence could be made regarding the other twins of the myth, Dalí’s sister Ana María being the mortal Clytemnestra, while Gala would represent divine Helen.[1] Salvador Dalí himself wrote: "I started to paint Leda Atómica which exalts Gala, the metaphysical goddess and succeeded to create the ‘suspended space’".

Dalí’s Catholicism enables also other interpretations of the painting. The painting can be conceived as Dalí's way of interpreting the Annunciation. The swan seems to whisper her future in her ear, possibly a reference to the legend that the conception of Jesus was achieved by the introduction of the breath of the Holy Ghost into the Virgin Mary’s ear. Leda looks straight into the bird's eyes with an understanding expression of what is happening to her and what will happen in the future to her and to her unsure reality. Dalí's transformation of Mary is the result of love as if he created his love to Gala, like God to Mary.[4]

Bibliography

- Jean-Louis Ferrier - Dalí, Leda atomica : anatomie d'un chef-d'oeuvre – Gonthier, Paris, 1980 - ISBN 978-2-282-30166-2

References

- 1 2 Maurell, Rosa M. (May 30, 2000). "Mythological References in the work of Salvador Dalí: the myth of Leda". Centre for Dalinian Studies. Hora Nova.

- 1 2 Elliott H. King - Dalí Atomicus, or the Prodigious Adventure of the Lacemaker and the Rhinoceros - Society for Literature and Science Annual Meeting October 10–13, 2002, Pasadena, California

- ↑ "And Now to Make Masterpieces - Time. December 8, 1947". Time.com. 1947-12-08. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ↑ Leda Atomica Archived February 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.