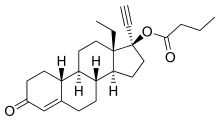

Levonorgestrel butanoate

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Intramuscular injection |

| ATC code | None |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms | LNG-B; HRP-002; Levonorgestrel 17β-butanoate; 17α-Ethynyl-18-methyl-19-nortestosterone 17β-butanoate; 17α-Ethynyl-18-methylestr-4-en-17β-ol-3-one 17β-butanoate |

| CAS Number | 86679-33-6 |

| PubChem (CID) | 3086228 |

| ChemSpider | 2342903 |

| UNII | L929CBB126 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C25H34O3 |

| Molar mass | 382.544 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

Levonorgestrel butanoate (LNG-B) (developmental code name HRP-002),[1][2] or levonorgestrel 17β-butanoate, is a steroidal progestin of the 19-nortestosterone group which was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in collaboration with the Contraceptive Development Branch (CDB) of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as a long-acting injectable contraceptive.[3][4] It is the C17β butanoate ester of levonorgestrel, and acts as a prodrug of levonorgestrel in the body.[4] The drug is at or beyond the phase III stage of clinical development, but has not been marketed at this time.[3] It was first described in the literature, by the WHO, in 1983, and has been under investigation for potential clinical use since then.[4][5]

LNG-B has been under investigation as a long-lasting injectable contraceptive for women.[6] A single intramuscular injection of an aqueous suspension of 5 or 10 mg LNG-B has a duration of 3 months,[3][6] whereas an injection of 50 mg has a duration of 6 months.[1] The drug was also previously tested successfully as a combined injectable contraceptive with estradiol hexahydrobenzoate, but this formulation was never marketed.[6] LNG-B has been tested successfully in combination with testosterone buciclate as a long-lasting injectable contraceptive for men as well.[7][8]

LNG-B may have several advantages over depot medroxyprogesterone acetate, including the use of much lower comparative dosages, reduced progestogenic side effects like hypogonadism and amenorrhea, and a more rapid return in fertility following discontinuation.[6][9] The drug has a well-established safety record owing to the use of levonorgestrel as an oral contraceptive since the 1960s.[6]

See also

References

- 1 2 Tekoa L. King; Mary C. Brucker; Jan M. Kriebs; Jenifer O. Fahey (21 October 2013). Varney's Midwifery. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 495–. ISBN 978-1-284-02542-2. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Shalender Bhasin (13 February 1996). Pharmacology, Biology, and Clinical Applications of Androgens: Current Status and Future Prospects. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 401–. ISBN 978-0-471-13320-9.

- 1 2 3 Benno Clemens Runnebaum; Thomas Rabe; Ludwig Kiesel (6 December 2012). Female Contraception: Update and Trends. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 429–. ISBN 978-3-642-73790-9.

- 1 2 3 Crabbé P, Archer S, Benagiano G, Diczfalusy E, Djerassi C, Fried J, Higuchi T (1983). "Long-acting contraceptive agents: design of the WHO Chemical Synthesis Programme". Steroids. 41 (3): 243–53. PMID 6658872.

- ↑ Benagiano, G., & Merialdi, M. (2011). Carl Djerassi and the World Health Organisation special programme of research in human reproduction. Journal für Reproduktionsmedizin und Endokrinologie-Journal of Reproductive Medicine and Endocrinology, 8(1), 10-13. http://www.kup.at/kup/pdf/10163.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 Paolo Giovanni Artini; Andrea R. Genazzani; Felice Petraglia (11 December 2001). Advances in Gynecological Endocrinology. CRC Press. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-1-84214-071-0.

- ↑ C. Coutifaris; L. Mastroianni (15 August 1997). New Horizons in Reproductive Medicine. CRC Press. pp. 101–. ISBN 978-1-85070-793-6.

- ↑ Shio Kumar Singh (4 September 2015). Mammalian Endocrinology and Male Reproductive Biology. CRC Press. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-1-4987-2736-5.

- ↑ Pramilla Senanayake; Malcolm Potts (14 April 2008). Atlas of Contraception, Second Edition. CRC Press. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-0-203-34732-4.