Liepāja massacres

| Liepāja massacres | |

|---|---|

|

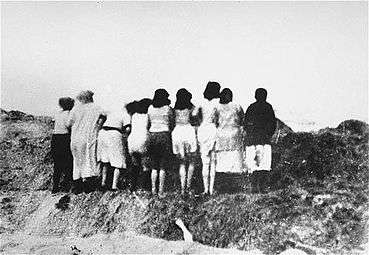

Members of a Latvian self-defence unit assemble a group of Jewish women for murder on a beach near Liepāja, December 15, 1941. | |

| Also known as | Libau, Šķēde, Shkeede, Skeden |

| Location | Liepāja, Latvia and vicinity, including Priekule, Aizpute, and Grobiņa |

| Incident type | Imprisonment, mass shootings, forced labor |

| Perpetrators | Viktors Arājs, Pēteris Galiņš, Fritz Dietrich, Erhard Grauel, Wolfgang Kügler, Hans Kawelmacher, Karl-Emil Strott |

| Organizations | Kriegsmarine, Einsatzgruppen, Ordnungspolizei, Wehrmacht, Arajs Kommando, Latvian Auxiliary Police |

| Victims | About 5,000 Jews. Lesser numbers of Gypsies, communists and the mentally ill were also killed. |

| Memorials | At Šķēde, Liepāja Central Cemetery |

The Liepāja massacres were a series of mass executions, many public or semi-public, in and near the city of Liepāja (German: Libau), on the west coast of Latvia in 1941 after the Nazi occupation of Latvia. The main perpetrators were detachments of the Einsatzgruppen, the Sicherheitsdienst or SD, the Ordnungspolizei, or ORPO, and Latvian auxiliary police and militia forces. Wehrmacht and German naval forces participated in the shootings.[1] In addition to Jews, the Nazis and their Latvian collaborators also killed Gypsies, communists, the mentally ill[1] and so-called "hostages".[2] In contrast to most other Holocaust murders in Latvia, the killings at Liepāja were done in open places.[3] About 5,000 of the 5,700 Jews trapped in Liepāja were shot, most of them in 1941.[2] The killings occurred at a variety of places within and outside of the city, including Rainis Park in the city center, and areas near the harbor, the Olympic Stadium, and the lighthouse. The largest massacre, of 2,731 Jews and 23 communists, occurred in the dunes surrounding the town of Šķēde, north of the city center. This massacre, which was perpetrated on a disused Latvian Army training ground, was conducted by Nazi and partisan forces from December 15 to 17, 1941.[2] More is known about the killing of the Jews of Liepāja than in any other city in Latvia except for Riga.[4]

German invasion

Liepāja was targeted by the Nazis as a town of special importance. It was a naval base and also an important international port. As such, the population was suspected of being more sympathetic to Communism.[5] The German army planned to capture the city on the first day of the war, Sunday, June 22, 1941. The attack on Liepāja was led by the German 291st Infantry Division.[6] Strong resistance by the Red Army and other Soviet forces prevented the Germans from entering the city until June 29, 1941, and resistance, including sniper fire, continued within the city for several days afterwards.[5] The city was heavily damaged in the fighting and fires burned for days.[5]

Shootings begin

In Latvia the Holocaust started on the night of June 23 to June 24, 1941, when in Grobiņa, a town near Liepāja, Sonderkommando 1a members killed six local Jews, including the town chemist, in the church graveyard.[7] Once Liepāja itself fell on June 29, 1941, "the hunt for the Jews began with the first hours of occupation."[8] Professor Ezergailis estimates that about 5,700 Jews of Liepāja and the surrounding district fell into German hands.[2]

On June 29 and June 30, 1941, there were random shootings of Jews in Liepāja by German soldiers.[9] About 99 Jews (plus or minus 30) were killed in these shootings.[9] Shootings began almost immediately. For example, at 5:00 p.m. on June 29, arriving German soldiers seized 7 Jews and 22 Latvians and shot them at a bomb crater in the middle of Ulicha street. At 9:00 p.m. the same day German soldiers came to Hika street, where they assembled all the residents and asked if any were refugees from Germany. One man, Walter (or Victor) Hahn, a conductor who had fled Vienna in 1938,[10] stepped forward and was immediately shot. (Another source says that Hahn was killed by a mob of Latvians fomented by Nazis.[10]) The next day, June 30, soldiers went to the City Hospital, arrested several Jewish physicians and patients, disregarded the protests of the Latvians on the hospital staff, and shot them. Among the victims was 10-year-old Masha Blumenau.[9]

Rainis Park massacre

On June 29, 1941, a detachment of Einsatzkommando 1a, (EK 1a) under SS-Obersturmbannführer Reichert entered Liepāja.[11] One of the first people EK 1a killed, on June 30, was the musician Aron Fränkel, who, not knowing that Einsatzkommando had set up headquarters at his place of employment, the Hotel St. Petersburg, showed up for work. He was identified as a Jew and immediately shot.[9]

During the fighting, the Soviet forces had dug defensive trenches in Rainis Park (Raiņa parks) in the center of Liepāja. On July 3 and 4, 1941, in their first documented massacre in Liepāja,[9] Reichert's EK 1a men, all Germans of the SD, rounded up Jews and marched them to these trenches in the park. Once at the trench, they were shot and the bodies pushed in. How many were killed during these shootings is not known.[11] Estimates range from several dozen to 300.[12] After the war, the Soviet Union investigatory commission concluded that 1,430 people were killed in the park shootings, which Professor Ezergailis characterizes as an exaggeration.[12] One participant, Harry Fredrichson, later testified that in one massacre he participated in, 150 people were killed.[11]

Anti-Jewish measures

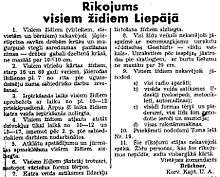

As a naval base, Liepāja came under the command of the German navy, the Kriegsmarine. Lieutenant commander (Korvettenkapitan) Stein was appointed as town commandant.[5] On July 1, 1941, Stein ordered that ten hostages be shot for every act of sabotage, and further put civilians in the zone of targeting by declaring that Red Army soldiers were hiding among them in civilian attire.[5] This was the first announcement in Latvia of a threat to shoot hostages.[5] On July 5, 1941 Korvettenkapitan Brückner, who had taken over for Stein[5] issued a set of anti-Jewish regulations.[14] These were published in a local newspaper, Kurzemes Vārds.[13] Summarized these were as follows:[15]

- All Jews must wear the yellow star on the front and back of their clothing;

- Shopping hours for Jews were restricted to 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon. Jews were only allowed out of their residences for these hours and from 3:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m.;

- Jews were barred from public events and transportation and were not to walk on the beach;

- Jews were required to leave the sidewalk if they encountered a German in uniform;

- Jewish shops were required to display the sign "A Jewish-owned business" in the window;

- Jews were to surrender all radios, typewriters, uniforms, arms and means of transportation.[15]

July 7 "hostage" shootings

On July 3 or 4, Erhard Grauel, commander of a detachment of Einsatzkommando 2, entered the city with about 30 men, most of them from Police Battalion 9 of the Ordnungspolizei. Reichert was then engaged in the Rainis Park shootings, which he described to Grauel as a "special assignment." Reichert left the day after Grauel arrived.[11] Grauel took over the Women's Prison and used it as a detention facility for the targets of the Nazi regime. Mostly they were Jews, but Communists and communist-sympathizers were also arrested. Rumors were spread that the Jews were responsible for the Communist atrocities during the Soviet regime in Liepāja. Latvian militia ("self-defense men") carried out most if not all of the arrests.[11] On July 6, 1941, Werner Hartman, a German war correspondent, saw the Women's Prison crammed so full of prisoners that there was no room for them to lie down.[11]

The first shootings carried out by Grauel were of about 30 Jews and Communists, arrested on July 5 through July 7[9] and executed on July 7, 1941 as "hostages" pursuant to Korvettenkapitan Stein's decree of July 1, supposedly in retaliation for shots having been fired at German patrols in the Liepāja vicinity.[11] Grauel had selected every fifth prisoner for execution, and Grauel's men shot them on the beach in the dunes near the lighthouse.[16] The numbers killed in the hostage massacre were stated as 30 in Grauel's postwar trial, and estimated at 27 plus or minus 16 by Anders and Dubrovskis.[9]

July 8–10 shootings

On or about July 7, 1941, Reichert returned to Liepāja, with a message from Franz Walter Stahlecker, commander of Einsatzgruppe A, that accused Grauel of not executing people fast enough. Grauel showed Reichert the list of people he had arrested. Reichert checked off a number of names on the list and demanded that they be shot immediately. Grauel ordered his assistant, one Neuman, to organize an execution. On July 8, 9, and 10, Grauel's men shot 100 men, almost entirely Jews, on each day. They were transported to the execution site from the Women's Prison in groups of 20.[16]

According to Hartman's later testimony, on July 8, he was present at the killing site from 11:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., and saw about 200 people killed. The procedure was for the Latvian "freedom fighters" (as they were called by Hartman) to drive the victims ten at a time into a long ditch that ended in a pit. There they would be aligned in a double row, and shot, generally by Germans, but possibly by Latvians. The area around the execution site was guarded by Germans and Latvians, the latter distinguishable by their red-white-red armbands.[16]

The early executions, which happened at least every two weeks, if not more often, were on the beach to the south of the lighthouse.[17] The initial execution squads were Germans, but were later replaced by a commando of Latvians.[17]

Grauel later testified at his post-war trial that he had requested to be relieved from command because of the stress of the massacres of 8 July to 10 July. His request was granted by the Einsatzkommando 2 commander, Rudolf Batz, and by the end of October, Grauel returned to Germany to study jurisprudence. Professor Ezergailis noted however, that before returning to Germany, and despite his claim to have been shocked by the July 8–10 massacres, Grauel went on from Liepāja to the nearby town of Ventspils, where he organized additional killings.[16]

July 24–25: First Arājs action

22 July 1941: "... Here about 8,000 Jews ... with present SS personnel this would take about 1 year, which is untenable for pacification of Libau."

27 July 1941: "Jewish problem Libau largely solved by execution of about 1,100 male Jews by Riga SS commando on 24 and 25.7."

—Hans Kawelmacher, Libau naval commandant.[18]

Grauel was replaced with SS-Untersturmführer (Second Lieutenant) Wolfgang Kügler on July 10 or 11.[16] Under Kügler's supervision, massacres occurred at a rate of about twice a week. Shootings of small groups of Jews continued after July 10, happening every evening. These were organized by Kügler.[19] Often these were of less than 10 individuals, which was a pattern particular to Kügler's administration in Liepāja. The exact number of those killed in these actions is not known, but was estimated by Anders and Dubrovskis to be 81 individuals plus or minus 27.[9][19] Anders and Dubrovskis estimate the total number of victims to be 387 individuals, plus or minus 130.[9]

On July 16, 1941, Fregattenkapitän Dr. Hans Kawelmacher was appointed the German naval commandant in Liepāja.[20] On July 22, Kawelmacher sent a telegram to the German Navy's Baltic Command in Kiel, which stated that he wanted 100 SS and fifty Schutzpolizei ("protective police") men sent to Liepāja for "quick implementation Jewish problem".[18] By "quick implementation" Kawelmacher meant "accelerated killing."[6] Mass arrests of Jewish men began immediately in Liepāja, and continued through July 25, 1941.[18] The Arājs commando was brought in from Riga to carry out the shootings, which occurred on July 24 and July 25.[21] About 910 Jewish men were executed, plus or minus 90.[18] Statements in other sources that 3,000 (Vesterman) and 3,500 (Soviet Extraordinary Commission) were killed are incorrect.[9][21]

This first Arājs action was later described by Georg Rosenstock, the commander of the second company of the 13th Police Reserve battalion. Rosenstock testified after the war that when he and his unit had arrived in Liepāja in July, 1941, they had heard from some passing marines that Jews were being continuously executed in the town, and these marines were going out to watch the executions.[22] A few days later, on Saturday, July 24, 1941, Rosenstock saw Jews (whom he identified by the yellow stars on their clothing) crouching down in the back of a truck, being guarded by armed Latvians. Rosenstock, who was himself in a vehicle, followed the truck to the north of the city to the beach near the naval base, where he saw Kügler, some SD men, and a number of Jews.[22]

The Jews were crouching down on the ground. They had to walk in groups of about ten to the edge of a pit. Here they were shot by Latvian civilians. The execution area was visited by scores of German spectators from the Navy and the Reichsbahn [national railway]. I turned to Kügler and said in no uncertain terms that it was intolerable that shootings were being carried out in front of spectators.[22]

Shootings from August to December 10

The killings continued at August after the first Arājs action, but on a lessened scale. From August 30 to December 10, 1941, there were a large number of shootings, in which about 600 Jews, 100 Communists, and 100 Gypsies were killed.[2][23] Anders and Dubrovskis estimate the total victims through August 15, 1941 as 153 plus or minus 68.[18] Schulz, a boatswain's mate (Oberbootsmaat) from the harbor surveillance command, testified that on a day August, 1941, he had heard continuous rifle salvoes all day coming from across the harbor from his position.[24]

Between 5:00 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. Schulz and another man rowed across the harbor to see what was happening. They followed the sounds of the shooting until they came to the old citadel. By standing on a bunker at the citadel they could see a long deep trench which was said to have been dug by the Jews the previous day. This was about one kilometer north of the lighthouse. They watched for about an hour or an hour and a half. During that time, three or four trucks arrived at the site, each carrying five Jews. They were forced to lie down in the truck. When the truck reached the site, the driver took the vehicle right up to the trench. Latvian guards, wielding clubs, forced the victims to enter directly into the trench. A squad of five men, possibly Latvians, but more probably German SD men, then shot them in the head. The supervising SS or SD officer then shot again any one not immediately killed.[24]

Massacres of the Gypsies

The Romani people (called "Gypsy" in English and Zigeuner in German) were also targets of the Nazi occupation.[25][26] On December 4, 1941, Hinrich Lohse issued a decree[27] which stated:

Gypsies who wander about in the countryside represent a two-fold danger.1. As carriers of contagious diseases, especially typhus; 2. As unreliable elements who neither obey the regulations issued by German authorities, nor are willing to do useful work. There exists well-founded suspicion that they provide intelligence to the enemy and thus damage the German cause. I therefore order that they are to be treated as Jews.[26]

Gypsies were also forbidden to live along the coast, which included Liepāja. On December 5, 1941, the Latvian police in Liepāja arrested 103 Gypsies (24 men, 31 women, and 48 children). Of these people, the Latvian police turned over 100 to the custody of the German police chief Fritz Dietrich "for follow up" (zu weiteren Veranlassung), a Nazi euphemism for murder.[26] On December 5, 1941, all 100 were all killed near Frauenburg.[26]

By May 18, 1942 the German police and SS commander in Liepāja indicated in a log that over a previous unspecified period, 174 Gypsies had been killed by shooting.[28] The German policy on Gypsies varied. In general, it seemed that wandering or "itinerate" Gypsies (vagabundierende Zigeuner) were targeted, as opposed to the non-wandering, or "sedentary" population. Thus, on May 21, 1942, the SS commander in Liepāja police and SS commander recorded the execution of 16 itinerate Gypsies from the Hasenputh district.[28] The documentation however does not always distinguish between different Gypsy groups, thus on April 24, 1942, EK A reported having killed 1,272 people, including 71 Gypsies, with no further description.[28]

December 15–17: "The Big Action"

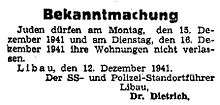

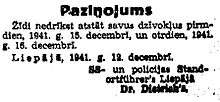

The largest of the Liepāja massacres took place on three days from Monday, December 15 to Wednesday, December 17, 1941. On December 13, Kurzemes Vārds published an order by Emil Diedrich, the Nazi police in Liepāja, which required all Jews in the city to remain in their residences on Monday, December 15 and December 16, 1941.[29] The order came from SD headquarters in Riga; whether it was received by Kügler or his deputy, Reichle, was disputed, with both Kügler and Reichle later claiming Kügler was on leave in Germany.[29] The Latvian police began arresting the Jews in the city on the night of December 13 to 14, bringing them to the Women's Prison, where they were confined in the courtyard. There was not enough room for the people, so they were ordered to stand facing towards the wall, and not move, look for relatives, or look at the guards, who beat people and treated them with brutality. There was an old wooden building, a garage, barn, or horse barn, at the beach at Šķēde. Some of the Jews were taken to this building on the evening of Sunday, December 14.[29]

Pēteris Galiņš, of whom little is known other than that he was killed in Russia in the winter of 1943,[30] was in charge of the Latvian guards, and he ordered a team of 20 to report for duty at 5:30 a.m. on December 15.[29]

The execution site was on the beach, north of the city, and north of the small barn or garage, which was used as a temporary holding point for the victims while their turn came to be executed. A trench had been dug in the dunes that ran parallel to the shore and was about 100 meters long and 3 meters wide.[29] Columns of Jews were formed at the Women's Prison and marched out under guard to the killing site.[31] The guards were Latvians with Germans acting as supervisors.[29]

Once at the site, the Jews were housed in the barn and taken in groups of 20 of a time to a point 40 or 50 meters from the trench, where they were ordered to lie face down on the ground. Groups of ten were then ordered to stand up, and, except for children, remove their outer clothing. As they were moved closer to the pit, they were ordered to strip completely. A Latvian guard, Bulvāns, later testified that he saw two Germans, SS-Scharführer[32] ("squad leader") Karl-Emil Strott[33] and Philip (or Filip) Krapp, using a whip on people who did not move on to the pit.[34]

The actual shootings were done by three units, one of Germans, another of Latvian SD men, and another unit of the Latvia police, apparently the one commanded by Galiņš. The victims were positioned along the edge of the sea side of the trench. They were faced away from their killers, who fired across the trench, with two gunman allocated to each victim. After the initial volley, a German SD man would step down into trench, inspect the bodies, and fire finishing shots into anyone left alive. The goal was to have the bodies fall into the trench, but this did not always happen. Accordingly, the executioners had a "kicker" come along after each group of victims. The kicker's job was to literally to kick, roll, or shove the bodies into the grave.[34] Sergeant Jauģietis of the Latvia police worked as a kicker for at least part of the killings.[31] Each execution team was relieved by another after killing 10 sets of victims.[34]

It was the practice of the persons commanding the executioners in Latvia to encourage drinking among at least the Latvian killing squads.[35] During the Liepāja killings, a milk can of rum was set up at the killing pits.[34][35] High-ranking Wehrmacht and Kriegsmarine officers visited the site during the course of the executions.[34]

Lucan, an adjutant of the 707th Marine Antiaircraft Detachment, described seeing an execution of 300 to 500 Liepāja Jews in the winter.[36] He saw a column of 300 to 500 Jews of all ages, men and women, being led under guard past his unit's headquarter's north on the road to Ventspils. The trench was 50 to 75 meters long, 2 to 3 meters wide and about 3 meters deep. Lucan did not see the actual shooting, but he and other members of his unit heard rifle fire coming from the direction of the pit for a long time.[36] Lucan inspected the site the next day:

The following day I went with several members of our unit ... to the execution area on horseback. When we arrived at the said hills we could see the arms and legs of the executed Jews sticking out of the inadequately filled-in grave. After seeing this, we officers sent a written communication to our headquarters in Liepāja. As a result of our communication the dead Jews were covered properly with sand.[36]

After the shootings, on January 3, 1942, Kügler reported to Fritz Dietrich, then in command of the Riga Order Police (German: Ordnungspolizei), that the executions were well known to the local population and had not been well-received:

Regret about the fate of the Jews is constantly expressed; there are few voices to be heard which are in favor of the elimination of the Jews. Among other things, a rumor is abroad that the execution was filmed in order to have material to use against the Latvian Schutzmannschaft. This material is said to prove that Latvians and not Germans carried out the executions.[37]

Spectators, participants, and photography

Many of the Liepāja executions were witnessed by persons other than the participants. Klee, Dressen, and Riess, in their study of the Holocaust perpetrators, concluded that the public executions were "in many ways a festival", that German soldiers traveled long distances to get the best places to witness the mass shootings, and that these public executions continued over a long period of time and became a form of "execution tourism.[38] Nobody was forced to murder Jews, and there were people who refused to do so. Nothing bad happened to them and in particular no one who refused was ever sent to a concentration camp.[38] At most, those who refused orders to kill were abused as "cowards" by their commanders.[39] This pattern was followed in Liepāja.[40] For example, a boatman who worked under the harbormaster, Navy personnel and at least one hundred Wehrmacht soldiers were present at an execution, apparently pursuant to orders.[41]

Richard Wiener, who photographed the Einsatzgruppen killings, went to the July or August massacres to take photographs. He found German soldiers standing around the execution site, not as participants, but as spectators.[42] Motion pictures were taken by Richard Wiener, on leave from his position as a German naval sergeant.[43] The December shootings at Šķēde were photographed by SS-Scharführer Karl-Emil Strott.[44] These became the best known images of the murders of Jews in Latvia, and they show only Latvians.[45] The photographs were found by David Zivcon, who worked as an electrician at the SD office in Liepāja. He found four rolls of film when he was repairing wiring in a German's apartment. Zivcon stole the film, had prints made, and returned the originals before they were missed. He then placed the prints in a metal box and buried them. After the Germans were driven out of Latvia, Zivcon retrieved the prints, which were later used in war crimes trials and displayed in museums around the world.[44] Professor Ezergailis also states that it was Kügler himself who photographed the shootings,[45] but of course if Kügler had been on leave, he couldn't have taken the photographs. Following the December shootings, the executioners repeatedly returned to the beach at Šķēde for killings, extending the trench along the dunes until it reportedly reached a length of one kilometer. In 1943, the grave was opened and chlorine cast over the bodies.[34]

Photographs of the December shootings

A group of Jewish women huddled together, waiting to be shot on the beach

A group of Jewish women huddled together, waiting to be shot on the beach Women and children forced to undress prior to shooting

Women and children forced to undress prior to shooting A Latvian guard leads Jewish women to the execution site

A Latvian guard leads Jewish women to the execution site Jewish women about to be shot by Nazis

Jewish women about to be shot by Nazis Immediately following the shooting. The man on the right is the "kicker", responsible for shoving the bodies into the pit.

Immediately following the shooting. The man on the right is the "kicker", responsible for shoving the bodies into the pit. Women forced to disrobe and then pose. Scholarly work has identified some of the women shown.[46]

Women forced to disrobe and then pose. Scholarly work has identified some of the women shown.[46]

The Liepāja ghetto

In June 1942, when the Liepāja ghetto was established, there were only about 814 surviving Jews. The ghetto itself consisted of only 11 houses on four streets. Until the ghetto was closed in October 1943, the inhabitants were used as a pool of forced labor for the occupying authorities. During that time 102 people died and 54 were executed. The ghetto guards were Latvians wearing black uniforms. Conditions were harsh and food was short. On October 8, 1943, Yom Kippur, the survivors of the Liepāja ghetto were loaded into cattle cars and shipped to Riga and the ghetto was closed. Only three Jews, who were barely alive, were left behind, two shoemakers and one goldsmith.[47]

Justice

- Viktors Arājs evaded justice for many years, but in 1979 he was convicted in a West German court and sentenced to life in prison {died 1988}.

- Fritz Dietrich was tried and convicted not for his crimes in Latvia, but for carrying out executions of Allied flyers in Germany. He was sentenced to death and executed in 1948.

- Wolfgang Kügler in a post war Crimes trial in West Germany-sentenced to 8 months in prison and a fine

- In 1971, a court in West Germany (Hannover Landgericht) convicted a number of the SD and Ordnungspolizei participants in the Liepāja massacres. The primary source of information about the Liepāja killings is the record developed in these proceedings.[4] The court imposed the following prison sentences[48]

- Paul Fahrman: one and one-years;

- Erhard Grauel: seven years;

- Gerhard Kuketta: two years

- Otto Reiche: five years;

- Georg Rosenstock: two and one-half years;

- Karl-Emil Strott: seven years;

Tabular summary

| Date | Location | Name | Commander | Participants | Units | Method | No. victims | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 Jul 41 | Liepāja | Rainis Park | Reichert | Frederichson | EK 2 | shooting | 200-300 | Jews |

| 7 Jul 41 | lighthouse | Grauel | shooting | 30 | hostages | |||

| 8-10 Jul 41 | Liepāja | Grauel | shooting | 300? | ||||

| 24-25 Jul 41 | First Arājs action | Kügler | Arājs | shooting | 910 | Jews | ||

| End Jul 41 | Ulleweit Action | Kügler | shooting | 15 | Jews | |||

| 22 Sep 41 | Liepāja | Kügler | shooting | 61 | Jews | |||

| 24 Sep 41 | Liepāja | Kügler | shooting | 61 | Jews | |||

| 25 Sep 41 | Liepāja | Kügler | shooting | 123 | Jews | |||

| 26 Sep 41 | Kügler | shooting | 80 | Jews and communists | ||||

| 30 Sep 41 | Kügler | shooting | 21? | Jews | ||||

| unknown | Courland | Kügler | shooting | 15-20 | Mentally ill | |||

| unknown | Courland | Kügler | shooting | 20 | Jews | |||

| 3 Oct 41 | Liepāja | Kügler | shooting | 37 | Jews | |||

| 4 Oct 41 | Liepāja | Kügler | shooting | 20 | 18 Jews and 2 communists | |||

| 8 Oct 41 | Liepāja | Kügler | shooting | 36 | Jews | |||

| 11 Oct 41 | Liepāja | Aktion Brückenwache | Kügler | shooting | 67 | Jews | ||

| about Oct 41 | Šķēde | Kügler | shooting | 200 | Jews | |||

| Oct 41 | Kügler | shooting | 25 | Jews | ||||

| Oct 41 | Kügler | shooting | 50-80 | Jews | ||||

| Oct 41 | Liepāja | Kügler | shooting | groups | Communists | |||

| Oct 41 | Šķēde | Aktion Linharts | Kügler | shooting | 33 | 30 men, 3 women | ||

| late Oct 41 | Kügler | shooting | 80 | Men, women, children | ||||

| late Oct 41 | Priekule | Kügler | shooting | 20 | Jews | |||

| 3 Nov 41 | Aizpute | shooting | 386 | Jews | ||||

| 6 Nov 41 | Liepāja | shooting | 5 | 2 Jews and 3 communists | ||||

| 10 Nov 41 | Liepāja | shooting | 56 | 30 Jews and 26 communists | ||||

| Beginning of Dec 41 | Šķēde | shooting | 100 | Gypsies | ||||

| 15-17 Dec 41 | Šķēde | shooting | 2,749 | Jews (men, women and children) | ||||

| 15 Dec 41 | Liepāja (by military harbor) | shooting | 270 | Jews | ||||

| Dec 41 | shooting | mentally ill | ||||||

| 15 Feb 42 | Šķēde | shooting | Jews | |||||

| beginning of March 42 | Šķēde | shooting | about 20 | Communists | ||||

| April 42 | Šķēde | shooting | 15-20 | men | ||||

| Late Mar 42 | shooting | 20 | Latvians | |||||

| summer 42 | Šķēde | shooting |

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Ezergailis 1996, pp. 292-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ezergailis 1996, pp. 286-7.

- ↑ Ezergailis 1996, p. 33 n.81.

- 1 2 Ezergailis 1996, p. 305 n.1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ezergailis 1996, pp. 286-7.

- 1 2 "Liepāja", pending article, Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos

- ↑ Ezergailis 1996, pp. 211-2..

- ↑ Ezergailis 1996, p. 286.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Anders & Dubrovskis 2003, pp. 127-8.

- 1 2 Schneider 1995, p. 155, citing Vestermann (1987).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ezergailis 1996, p. 290.

- 1 2 Ezergailis 1996, p. 306 n.67.

- 1 2 "Rikojums visiem zidiem Liepaia" (PDF). Kurzemes Vārds (in Latvian) (4). 5 July 1941. p. 1. Retrieved May 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) Online version from National Library of Latvia website. - ↑ Ezergailis 1996, p. 209.

- 1 2 Ezergailis 1996, p. 233 n.26, p. 287.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ezergailis 1996, p. 291.

- 1 2 Statement (excerpt) of SD interpreter Paul Fahrbach, given to the Hamburg Landsgericht, 16 April 1964, translated and reprinted in Klee, Dressen & Riess (1991, p. 126 - source p. 285).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anders & Dubrovskis 2003, pp. 126-7.

- 1 2 Ezergailis 1996, pp. 295-6.

- ↑ Vestermanis 2000, p. 224.

- 1 2 Ezergailis 1996, p. 308 n.33.

- 1 2 3 Statement (excerpt) of police commander Rosenstock, given to the Hamburg Landsgericht, 1 July 1964, translated and reprinted in Klee, Dressen & Riess (1991, pp. 127-8 - source p. 285).

- ↑ Lewy, at 153-156

- 1 2 Statement (excerpt) of boatswain's mate Schulz, given to the Hamburg Landsgericht, 10 Sept 1964, translated and reprinted in Klee, Dressen & Riess (1991, pp. 129, 133 - source p. 285).

- ↑ Niewyk, The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust, at 47.

- 1 2 3 4 Lewy, The Nazi Persecution of the Gypsies, at page 123.

- ↑ Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, at page 1073.

- 1 2 3 Lewy, The Nazi Persecution of the Gypsies, at 124

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ezergailis 1996, pp. 293-4.

- ↑ Ezergailis 1996, p. 308 n.89.

- 1 2 Ezergailis 1996, p. 308 nn.90-1.

- ↑ Strott's rank (Scharführer) is given at Ezergailis 1996, p. 383.

- ↑ His name is also seen as Carl Strott and Carl-Emil Strott.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ezergailis 1996, p. 294.

- 1 2 Ezergailis 1996, p. 105.

- 1 2 3 Statement (excerpt) of adjutant Lucan, given to the Hamburg Landsgericht, 15 July 1959, translated and reprinted in Klee, The Good Old Days, at pages 129 and 133, with source given at page 285

- ↑ Letter from Wolfgang Kügler to Fritz Dietrich, 3 January 1941, translated (excerpt only) and reprinted in Klee, The Good Old Days, at pages 134-135

- 1 2 Klee, The Good Old Days, "Introduction", at page xx

- ↑ Klee, The Good Old Days, "Foreword", by Lord Dacre of Glanton, page xiii.

- ↑ Klee, The Good Old Days, at pages 126 to 135

- ↑ Statement (excerpt) of boatman Vandrey, given to the Hamburg Landsgericht, 17 July 1959, translated and reprinted in Klee, The Good Old Days, at page 127 with source given at page 285.

- ↑ Struk, Photographing the Holocaust, at page 70

- ↑ Haggith, Holocaust and the Moving Image, at page 13, n.23, and page 27.

- 1 2 Yad Vashem, The Righteous Among the Nations", featured stories: "The visual evidence of the murder of the Jews of Liepaja"

- 1 2 Ezergailis 1996, p. 57 n.48.

- ↑ Anders and Dubrovskis identify these women, from left to right, as: (1) Sorella Epstein; (2) believed to be Rosa Epstein, mother of Sorella; (3) unknown; (4) Mia Epstein; (5) unknown. Alternatively, (2) may be Paula Goldman, and Mia Epstein may be (5) instead of (4).

- ↑ Ezergailis 1996, p. 304.

- ↑ (German) Hannover Landgericht, Strafurteil gegen Grauel, 711014 (on-line database case summary 760)

- ↑ Ezergailis 1996, pp. 296-7.

References

Historiographical

- Anders, Edward; Dubrovskis, Juris (2003). "Who Died in the Holocaust? Recovering Names from Official Records". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. Oxford University Press. 17 (1). See online version in Project Muse.

- Dribins, Leo, Gūtmanis, Armands, and Vestermanis, Marģers, Latvia's Jewish Community: History, Tragedy, Revival (2001), available the website of the Latvian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Dribin, Leo, Kurzeme's and Zemgale's Jews, University of Latvia website

- Ezergailis, Andrew (1996). The Holocaust in Latvia 1941–1944 The Missing Center. Riga: Historical Institute of Latvia in association with USHMM. ISBN 978-9984905433.

- Haggith, Toby, and Newman, Joanna, Holocaust and the Moving Image: Representations in Film and Television since 1933, London ; New York : Wallflower, 2005 ISBN 1-904764-52-5

- Hancock, Ian, "Genocide of the Roma in the Holocaust", Excerpted from Charny, Israel, W., Encyclopedia of Genocide (1997) available on-line at the Patrin Web Journal at the Wayback Machine (archived October 26, 2009)

- Hilberg, Raul, The destruction of the European Jews, (3d ed.) New Haven, Connecticut ; London : Yale University Press 2003 ISBN 0-300-09592-9

- Jewish community of Latvia website

- Kaufmann, Max, Die Vernichtung des Judens Lettlands (The Destruction of the Jews of Latvia), Munich, 1947, English translation by Laimdota Mazzarins available on-line as Churbn Lettland -- The Destruction of the Jews of Latvia

- Klee, Ernst; Dressen, Willi; Riess, Volker (1991). The Good Old Days - The Holocaust as Seen by its Perpetrators and Bystanders. (translation by Deborah Burnstone). New York: MacMillan. ISBN 0-02-917425-2.

- "Liepāja", article to be published in Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, Vol. 2, by U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Lewy, Guenter, The Nazi Persecution of the Gypsies, Oxford University Press 2000 ISBN 0-19-512556-8

- Lumans, Valdis O., Latvia in World War II, Fordham University Press, New York, 2006 ISBN 0-8232-2627-1

- Niewyk, Donald L., and Nicosia, Francis R., The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust, New York : Columbia University Press, 2003

- Roseman, Mark, The Wannsee Conference and the Final Solution—A Reconsideration, Holt, New York, 2002 ISBN 0-8050-6810-4

- Schneider, Gertrude, Muted voices : Jewish survivors of Latvia remember, New York : Philosophical Library, 1987.

- Schneider, Gertrude (1995). Exile and Destruction: the fate of Austrian Jews, 1938–1945. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0275951399.

- Struk, Janina, Photographing the Holocaust—Interpreting the Evidence, London ; New York : I.B. Tauris, 2004 ISBN 1-86064-546-1

- Vestermann, Aaron (1987). "Survival in a Libau Bunker". In Schneider, Gertrude. Muted Voices: Jewish Survivors of Latvia Remember. Philosophical Library. ISBN 978-0802225368.

- Vestermanis, Margers (2000). "Local Headquarters Liepaja: Two Months of German Occupation in the Summer of 1941". In Heer, Hannes; Nauman, Klaus; Shelton, Roy. War of extermination : the German military in World War II, 1941-1944. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 219–236. ISBN 978-1571812322.

War crime trials and evidence

-

Works related to Directions concerning treatment of Jewish property 13 October 1941 at Wikisource

Works related to Directions concerning treatment of Jewish property 13 October 1941 at Wikisource -

Works related to Comprehensive report of Einsatzgruppe A up to 15 October 1941 at Wikisource

Works related to Comprehensive report of Einsatzgruppe A up to 15 October 1941 at Wikisource - Stahlecker, Franz W., "Comprehensive Report of Einsatzgruppe A Operations up to 15 October 1941", Exhibit L-180 (excerpts of extensive report), translated and reprinted in Office of the United States Chief of Counsel For Prosecution of Axis Criminality, Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, Volume VII, pages 978-995, USGPO, Washington, D.C. 1946 ("Red Series")

- Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10, Nuernberg, October 1946 - April 1949, Volume IV, ("Green Series) (the "Einsatzgruppen case") also available at Mazel library (well indexed HTML version)

Newsreels and films

- Film of mass shootings at Liepāja (This is a short film about 1.5 minutes long, taken of a July or August 1941 shooting by a German soldier, Richard Wiener.)

- (German) Fritz Bauer Institut · Cinematographie des Holocaust (describes in detail the provenance and contents of the Reinhard Wiener film of the July or August 1941 shooting at Liepāja)

External links

-

Media related to The Holocaust in Latvia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Holocaust in Latvia at Wikimedia Commons - Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia, Holocaust Education, Research and Remembrance in Latvia, 16 Sept 2003

- (Latvian) Kurzemes Vārds (website of National Library of Latvia, includes chronologically indexed digital copies of Liepāja newspaper published under Nazi control during occupation of Latvia from 1941 to 1944.)

- The Killing Fields of Skede (Website includes modern images of: the beach at Šķēde; the Women's Prison in Libau; the Soviet memorial; and the 2005 memorial and dedication ceremony)

- Liepajajews.org (modern aerial images of trench at shooting site at Šķēde)

- link