Meron, Israel

| Meron מירון ميرون | |

|---|---|

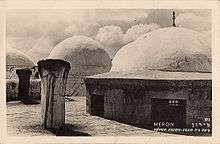

|

The tomb of Shimon bar Yochai in Meron | |

Meron | |

| Coordinates: 32°59′0″N 35°26′0″E / 32.98333°N 35.43333°ECoordinates: 32°59′0″N 35°26′0″E / 32.98333°N 35.43333°E | |

| District | Northern |

| Council | Merom HaGalil |

| Affiliation | Hapoel HaMizrachi |

| Founded | 1949 |

| Population (2015)[1] | 898 |

Meron (Hebrew: מֵירוֹן, Meron) is a moshav in northern Israel. Located on the slopes of Mount Meron in the Upper Galilee near Safed, it falls under the jurisdiction of Merom HaGalil Regional Council. In 2015 it had a population of 898.

Meron is most famous for the tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, and is the site of annual mass public commemoration of Lag Ba'omer.

The association of Meron with the ancient Canaanite city of Merom or Maroma is generally accepted by archaeologists. According to Avraham Negev, by the Second Temple period, Merom was known as Meron. Meron is mentioned in the Bible as the site of Joshua's victory over the Canaanite kings.[2] In the 12th century, Benjamin de Tudela visited Meron and described a cave of tombs located there believed to hold the remains of Hillel, Shammai, and "twenty of their disciples and other Rabbis". Until at least 1931, Meron consisted of an Arab and Jewish quarter (see Meiron). The modern village of Meron was founded in 1949 on the site of the ancient settlement by Orthodox soldiers discharged after the war.[3]

Geography

Among the local attractions are the Meron Vineyards. Meron is conducive to growing grapes for wine as a result of its 600-meter altitude and chalky soil. The vineyard was first planted in 2000 and is part of the Galil Mountain Winery, headquartered in nearby Kibbutz Yiron.[4]

History

Ancient

The association of Meron with the ancient Canaanite city of Merom or Maroma is generally accepted, though the absence of hard archaeological evidence means other sites a little further north, such as Marun as-Ras or Jebel Marun, have also been considered.[5][6] Merom is mentioned in 2nd milleniun BCE Egyptian sources, and in Tiglath-pileser III's accounts of his expedition to the Galilee in 733–732 BCE (where it is transcribed as Marum).[5][6]

Soundings conducted below the floors of houses excavated in the 1970s indicate the presence of even earlier structures with a different layout. While these lower levels have not yet been excavated, the possibility that they date back to the Early Bronze Age was not ruled out by the archaeologists. A handful of artifacts dating to the Early Bronze Age, including seal impressions and a basalt bowl, were also found during the digs.[7]

According to Avraham Negev, an Israeli archaeologist, by the Second Temple period, Merom was known as Meron.[7] It is mentioned in the Talmud as being a village in which sheep were reared, that was also renowned for its olive oil.[8][9] The Reverend R. Rappaport ventured that merino, the celebrated wool, may have its etymological roots in the name for the village.[8]

Classical Antiquity

Excavations at Meron found artifacts dating to the Hellenistic period at the foundation of the site.[10] The economic and cultural affinities of the inhabitants of the Meron area at this time were directed toward the north, to Tyre and southern Syria in general.[10] Josephus fortified Meron in the 1st century CE and called the town Mero or Meroth; however, Negev writes that Meroth, another ancient town, was located further north, possibly at the site of Marun as-Ras.[7]

A tower which still stands at a height of 18 feet (5.5 m) was constructed in Meron in the 2nd century CE.[9] In the last decade of the 3rd century CE, a synagogue was erected in the village. Known as the Meron synagogue, it survived an earthquake in 306 CE, though excavations at the site indicate that it was severely damaged or destroyed by another earthquake in 409 CE.[11][12] "One of the largest Palestinian synagogues in the basilica style", it is the earliest example of the so-called 'Galilean' synagogue, and consists of a large room with eight columns on each side leading to the facade and a three-doored entrance framed by a columned portico.[11][13] Artifacts uncovered during digs at the site include a coin of Probus (276–282 CE) and African ceramics dating to the latter half of the 3rd century, indicating that the city was commercially prosperous at the time.[11] Coins found in Mieron are mostly from Tyre, though a large number are also from Hippos, which lay on the other side of Lake Tiberias.[13] Peregrine Horden and Nicholas Purcell write that Meron was a prominent local religious centre in the period of late Antiquity.[14] Some time in the 4th century CE, Meron was abandoned for reasons as yet unknown.[15]

Islamic era

Denys Pringle describes Meron as a "[f]ormer Jewish village", with a synagogue and tombs dating to the 3rd and 4th centuries, noting the site was later reoccupied between 750 and 1399.[16]

In the 12th century, Benjamin de Tudela, a Navarrese rabbi, visited Meron and described a cave of tombs located there believed to hold the remains of Hillel, Shammai, and "twenty of their disciples and other Rabbis".[17] On his visit to Meron in 1210, Samuel ben Samson, a French rabbi, located the tombs of Shimon Bar Yochai and his son Eleazar b. Simeon there.[17] A contemporary of the second Jewish revolt against Rome (132–135 CE), Bar Yochai is venerated by Moroccan Jews, whose veneration of saints is thought to be an adaptation of local Muslim customs.[18] From the 13th century onward, Meron became the most frequented site of pilgrimage for Jews in Palestine.[14]

In the early 14th century, Arab geographer al-Dimashqi mentioned Meron as falling under the administration of Safad. He reported that it was located near a "well-known cave" where Jews and possibly non-Jewish locals traveled to celebrate a festival, which involved witnessing the sudden and miraculous rise of water from basins and sarcophagi in the cave.[19]

Palestine was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517, and by 1596, Meron was a large village of 715 located in the nahiya ("subdistrict") of Jira, part of Sanjak Safad. The village paid taxes on goats, beehives, and a press that processed either grapes or olives.[20]

Meron suffered relatively minor damage in the Galilee earthquake of 1837. It was reported that during the earthquake the walls of the tombs of Rabbi Eleazer and Rabbi She-Maun were dislodged, but did not collapse.[21]

A number of European travellers came to Meron over the course of the 19th century and their observations from the time are documented in travel journals. Edward Robinson, who visited Meron during his travels in Palestine and Syria in the mid-19th century, describes it as "a very old looking village situated on a ledge of bristling rocks near the foot of the mountain. The ascent is by a very steep and ancient road [...] It is small, and inhabited only by Muhammedans."[17] The tombs of Shimon bar Yochai, his son rabbi Eleazar and those of Hillel and Shammai are located by Robinson as lying within a khan-like courtyard underneath low-domed structures that were usually kept closed with the keys held in Safad. Robinson indicates that this place was the focal point of Jewish pilgrimage activities by his time; the synagogue is described as being in ruins.[17]

Laurence Oliphant also visited Meron sometime in the latter half of the 19th century. His guide there was a Sephardic rabbi who owned the land that made up the Jewish quarter of the village. Oliphant writes that the rabbi had brought 6 Jewish families from Morocco to till the land, and that they and another 12 Muslim families made up the whole of the village's population at the time.[22] Karl Baedeker described it as a small village that appeared quite old with a Muslim population. By the late 19th century, Meron was a small village of 50 people who cultivated olives.[20][23]

British Mandate of Palestine

Towards the end of World War I, the ruins of the Meron synagogue were acquired by the "Fund for the Redemption of Historical Sites" (Qeren le-Geulat Meqomot Histori'im), a Jewish society headed by David Yellin.[24] Until at least 1931, Meron consisted of an Arab and Jewish quarter, with the former being the larger one and the latter being built around the tomb of bar Yochai. That year, there were 259 Arabs and 31 Jews. Sami Hadawi's 1945 survey, conducted toward the end of the British Mandate in Palestine, depicted an entirely Arab population. Meron had a boy's elementary school. Agriculture and livestock was the dominant economic sectors of the village, with grain being the primary crop, followed by fruits. Around 200 dunams of land were planted with olive trees, and there were two presses in the village used to process olives.[20]

1948 War

Meron's, then known as Meiron, Arab inhabitants were driven out or fled during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[25]

2006 Lebanon–Israel War

On July 14, 2006, a Katyusha rocket fired from Lebanon exploded in Meron, claiming 2 lives—Yehudit Itzkovich, 57, and her 7-year-old grandson Omer Pesachov—and injuring four others. A new barrage of rockets hit Moshav Meron on July 15; there were no injuries.

Tomb of Shimon Bar Yochai

Meron is most famous for the tomb of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, a first-century rabbi, who contributed greatly to the Mishna, is often quoted in the Talmud, and to whom is attributed authorship of the kabbalistic book of the Zohar. During the annual mass public commemoration of Lag BaOmer, hundreds of thousands of Jews make a pilgrimage to the site. With torches, song and feasting, the Yom Hillula is celebrated by tens of thousands of people. This celebration was a specific request by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai of his students. It is a custom at the Meron celebrations, dating from the time of Rabbi Isaac Luria, that three-year-old boys are given their first haircuts (upsherin), while their parents distribute wine and sweets.[26]

References

- ↑ "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Mordecai Schreiber, Alvin I. Schiff, Leon Klenicki. The Shengold Jewish Encyclopedia. p. 180

- ↑ See below.

- ↑ http://www.galilmountain.co.il/English/About

- 1 2 Aharoni and Rainey, 1979, p. 225.

- 1 2 Bromiley, 1995, p. 326.

- 1 2 3 Negev and Gibson, 2005, p. 332.

- 1 2 Ben Jonah et al., 1841, pp. 107–108.

- 1 2 Negev and Gibson, 2005, p. 330.

- 1 2 Zangenberg et al., 2007, p. 155.

- 1 2 3 Urman and Flesher, 1998, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Safrai, 1998, p. 83.

- 1 2 Stemberger and Tuschling, 2000, p. 123.

- 1 2 Horden and Purcell, p. 446.

- ↑ Groh, in Livingstone, 1987, p. 71.

- ↑ Pringle, 1997, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 Robinson, 1856, p. 73.

- ↑ Friedland and Hecht, 1996, p. 86.

- ↑ al-Dimashqi quoted in Khalidi, 1992, p. 476.

- 1 2 3 Khalidi, 1992, p.477.

- ↑ Neman, 1971, cited in "The earthquake of 1 January 1837 in Southern Lebanon and Northern Israel" by N. N. Ambraseys, in Annali di Geofisica, Aug. 1997, p.933,

- ↑ Oliphant, 1886, p.75.

- ↑ Laurence Oliphant, Haifa, or Life in Modern Palestine. ISBN 978-1-4021-7864-1

- ↑ Fine, 2005, p. 23.

- ↑ Morris, 2004, p. xvi, village #56.

- ↑ David M. Gitlitz & Linda Kay Davidson Pilgrimage and the Jews (Westport: CT: Praeger, 2006) 89–91, 146–149.

External links

Bibliography

- Aharoni, Yohanan; Rainey, Anson F. (1979), The Land of the Bible: A Historical Geography, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 9780664242664

- Ben Jonah, Tudela Benjamin (1841), The Itinerary of Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, Asher

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1995), The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: A–Z, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 9780802837851

- Fine, Steven (2005), Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World: Toward a New Jewish Archaeology, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521844918

- Friedland, Roger; Hecht, Richard D. (1996), To Rule Jerusalem, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521440462

- Gitlitz, David M. & Linda Kay Davidson. Pilgrimage and the Jews (Westport: CT: Praeger, 2006). ISBN 0-275-98763-9

- Horden, Peregrine; Purcell, Nicholas (2000), The Corrupting Sea: A Study of Mediterranean History, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 9780631218906

- Groh, D.E. (1989), Elizabeth A. Livingstone, ed., Papers Presented to the Tenth International Conference on Patristic Studies Held in Oxford 1987, Peeters Publishers, ISBN 9789068312317

- Negev, Avraham; Gibson, Shimon (2005), Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 9780826485717

- Pringle, Denys (1997), Secular Buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: An Archaeological Gazetteer, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521460101

- Stemberger, Günter; Tuschling, Ruth (2000), Jews and Christians in the Holy Land: Palestine in the Fourth Century, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 9780567086990

- Urman, Dan; Flesher, Paul Virgil McCracken (1998), Ancient Synagogues: Historical Analysis and Archaeological Discovery, BRILL, ISBN 9789004112544

- Zangenberg, Jürgen; Attridge, Harold W.; Martin, Dale B. (2007), Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in Ancient Galilee: A Region in Transition, Mohr Siebeck, ISBN 9783161490446