Military career of Benedict Arnold, 1781

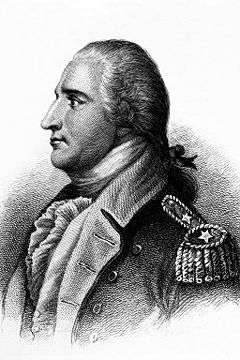

| Benedict Arnold V | |

|---|---|

Benedict Arnold Copy of engraving by H.B. Hall after John Trumbull | |

| Born |

January 14, 1741 Norwich, Connecticut |

| Died |

June 14, 1801 (aged 60) London, England |

| Place of burial | London |

| Service/branch |

British colonial militia Continental Army British Army |

| Years of service |

British colonial militia: 1757, 1775 Continental Army: 1775–1780 British Army: 1780–1781 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Commands held | American Legion (a Loyalist regiment) |

| Battles/wars | |

The military career of Benedict Arnold in 1781 consisted of service in the British Army. Arnold had changed sides in September 1780, after his plot was exposed to surrender the key Continental Army outpost at West Point. He spent the rest of 1780 recruiting Loyalists for a new regiment called the American Legion. Arnold was then sent to Virginia with 1,600 men in late December by General Sir Henry Clinton, with instructions to raid Richmond and then establish a strong fortification at Portsmouth.

He landed in Virginia on January 4, 1781 and raided Richmond the next day. They raided a few nearby communities, then returned to Portsmouth, where the troops established fortifications. They remained there until late March, when 2,000 reinforcements arrived, led by General William Phillips. Phillips took command of the forces and Arnold served under him, as they resumed raiding operations aimed at potentially establishing a permanent presence at Richmond. They fought off a spirited militia defense in the Battle of Blandford in late April, and the timely arrival of Continental forces under the Marquis de Lafayette prevented the taking of Richmond. Phillips continued to raid, but was ordered to Petersburg to effect a junction with General Charles Cornwallis, who was marching up from North Carolina. Phillips died on May 13 of a fever, and Arnold was briefly in command again until Cornwallis arrived a week later. Arnold returned to New York, suffering from a recurrence of gout.

French and American movements to encircle Cornwallis at Yorktown became apparent to General Clinton, so he sent Arnold on a raiding expedition in early September to New London, Connecticut in an attempt to draw American resources away from Virginia. Arnold raided the port, but a detachment of his troops was involved in the bloody Battle of Groton Heights at a fort across the Thames River. The operation was the last command that Arnold held. General Cornwallis had been released on parole after his surrender at Yorktown, and he Arnold and sailed for England in December.

During his command of British troops, Arnold did not gain a great deal of respect from other officers. His actions in Virginia and Connecticut were criticized, and allegations circulated in New York that he was primarily interested in money. On his arrival in England, he was also unable to acquire new commands, either in the army or with the British East India Company. He resumed his business and trade activities, and died in London in 1801.

Background

Benedict Arnold was born in 1741 into a well-to-do family in the port city of Norwich in the colony of Connecticut.[1] He was interested in military affairs from an early age, serving briefly (without seeing action) in the colonial militia during the French and Indian War in 1757.[2] He embarked on a career as a businessman, first opening a shop in New Haven and then engaging in overseas trade. He owned and operated ships, sailing to the West Indies, New France, and Europe.[3] When the British Parliament began to impose taxes on its colonies, Arnold's businesses began to be affected by them and the resulting opposition, which he eventually joined.[4] In 1767, he married a local woman with whom he had three children, one of whom died in infancy.[5][6] She died in 1775, and Arnold left his children under the care of his sister Hannah at his home in New Haven.[7]

Continental Army service, 1775–1780

Arnold had distinguished himself early in the war, participating in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775 and then boldly leading a raid on Fort Saint-Jean near Montreal.[7] He then led a small army from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Quebec City on an expedition through the wilderness of present-day Maine, where he was wounded in the climactic Battle of Quebec on December 31, 1775. After leading an ineffectual siege of Quebec until April 1776, he took over the military command of Montreal.[8] He directed the American retreat from there on the arrival of British reinforcements, and his forces formed the rear guard of the retreating Continental Army as it headed south toward Ticonderoga. Arnold then organized the defense of Lake Champlain, and led the Continental Navy fleet that was defeated in the October 1776 Battle of Valcour Island.[9]

During these actions, Arnold made a number of friends and a larger number of enemies within the army power structure and in Congress. He established a decent relationship with George Washington, commander of the army, as well as with Philip Schuyler and Horatio Gates, both of whom had command of the army's Northern Department at different times during 1775 and 1776.[10] However, an acrimonious dispute arose with Moses Hazen, commander of the 2nd Canadian Regiment, which boiled into a court martial of Hazen at Ticonderoga during the summer of 1776. Only action by Gates, his superior at Ticonderoga, prevented his own arrest on countercharges leveled by Hazen.[11] He also had disagreements with John Brown and James Easton, two lower-level officers with political connections. His conflict with them resulted in ongoing suggestions of improprieties on his part. Brown was particularly vicious, publishing a handbill that claimed of Arnold, "Money is this man's God, and to get enough of it he would sacrifice his country".[12]

In December 1776, Washington sent Arnold to coordinate the defense of Rhode Island after the British occupied Newport. No offensive action was possible, due to inadequate supplies and militia training.[13] In February 1777, Arnold was passed over by Congress for promotion to major general—along with several other brigadiers. While en route to Philadelphia to discuss the matter, he stopped in New Haven to visit his family, and fought in the rearguard Battle of Ridgefield against a British raiding party in which his left leg was injured once again.[14] In Philadelphia, Arnold threatened to resign over the issue of rank, but demurred when it was learned that Ticonderoga had fallen. He was sent north to assist in the defense of the Hudson River valley, and he helped lift the Siege of Fort Stanwix in August, and then played key roles in the two Battles of Saratoga in September and October. He was stripped of his command after the first battle in a dispute with General Gates, who had come to see Arnold as a competitor for rank and glory. Midway through the second battle, he rode to the battlefield anyway and led the troops in a spirited attack on two British redoubts, suffering serious injuries to his leg.[15]

Arnold recovered from his injuries, though he walked with a cane for the rest of his life, and Washington gave him the military command of Philadelphia after the British withdrew from the city in May 1778. There his actions increased political opposition to him, and further inquiries were made into his affairs.[16] He also began consorting with Loyalist sympathizers, and married Peggy Shippen, the daughter of one such man.[17] Shortly after, he opened negotiations with British General Sir Henry Clinton, mediated by British Major John André, offering his services to their side.

He resigned his Philadelphia command in anger after poor treatment by Congress and local opponents. He then sought the command of West Point, the key Continental Army base on the Hudson River, and acquired it in July 1780. He began to comply with plans to make it easier for the British to defeat West Point, systematically weakening its defenses.[18] The plot was exposed in September 1780 when American forces captured Major André; Arnold fled to New York and was given a commission as a brigadier general in the British Army.[19] Major André was hanged as a spy, greatly upsetting the British.[20]

British Army service

The British gave Arnold a brigadier general's commission with an annual income of several hundred pounds, but they only paid him £6,315 plus an annual pension of £360 because his plot failed.[21] He and his wife settled in New York, where the Loyalist elites at first snubbed them, but they were eventually overcome by Peggy's charm.[22] Arnold began recruiting a new Loyalist regiment called the American Legion, enrolling his young sons in the unit (at least on paper).[23] General Clinton then assigned Arnold to lead an expedition to the Chesapeake Bay. As his force began to take shape in November and December, rumors swirled in the city that many officers were refusing to serve under him.[24] Many of the British soldiers in New York held Arnold responsible for the death of the popular Major André.[25]

Arnold's preparations for the Chesapeake Bay expedition interrupted a scheme to kidnap him which was hatched by George Washington and Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee. Pursuant to the plan, Lee's sergeant major John Champe staged a "desertion" from Lee's unit in New Jersey to British lines in New York late in October 1780, and convinced Arnold to take him on as a senior noncommissioned officer.[26] Champe was supposed to make contact with covert operatives working in New York, with whom he would work to kidnap Arnold. After observing Arnold's habits, a plan was developed to be executed on the night of December 11.[27] Arnold ordered his troops to embark on transports on December 11—including Champe—thus scuttling the attempt.[28] Champe participated in the start of the expedition, and finally managed to escape several weeks later and return to Lee's unit. Washington and Lee rewarded him richly, and convinced him to retire from military service so that he would not risk hanging for his role in the affair if he was captured.[29]

Virginia

Arnold's force of 1,600 troops arrived off Virginia on January 1, 1781, landing on January 4. They captured Richmond by surprise and then went on a rampage through Virginia, destroying supply houses, foundries, and mills.[30] This activity brought out Virginia's militia, led by Colonel Sampson Mathews, initiating Arnold's return to Portsmouth to hold the port there. [31] The relative inactivity of holding the port led Arnold to request a change of command. Reinforcements arrived in March, led by William Phillips who had served under Burgoyne at Saratoga, and he took over the command. However, Clinton did not issue orders recalling Arnold, so he accompanied Phillips on new raiding expeditions into the Virginia countryside. The force advanced on Petersburg, where they defeated a militia force led by Baron von Steuben at the Battle of Blandford in late April. The arrival at Richmond of the Marquis de Lafayette and 900 Continental troops sent by General Washington to oppose Arnold prompted Phillips to begin making his way back to Portsmouth. While en route, they were ordered to return to Petersburg by Charles Cornwallis, the commander of the British southern army, where he would join them with his force. Phillips fell ill on the way and died of a fever at Petersburg on May 12.

Arnold commanded the army only until May 20, when Cornwallis arrived to take over. One colonel wrote to Clinton of Arnold, "there are many officers who must wish some other general in command".[32] Cornwallis disregarded advice proferred by Arnold to locate a permanent base away from the coast that might have averted his later surrender at Yorktown.[32] Shortly after Cornwallis's arrival, Arnold suffered a severe attack of gout and returned to New York.[33]

During Arnold's time in Virginia, two things happened that had a negative impact on his reputation. He wrote a letter to Lord George Germain, the British colonial secretary, criticizing Clinton's conduct of the war. Word of this communication reached Clinton, and Arnold was met with a frosty reception on his return to New York, and with assignments to perform menial administrative tasks.[34] Arnold attempted to make amends, writing to Germain, "I find my letter has given umbrage; I am extremely sorry for it."[35]

The second incident was a dispute with his naval counterpart on the Chesapeake, Captain Thomas Symonds, over the distribution of prizes captured during the various expeditions. Symonds was so incensed by Arnold's attitude that he refused to leave port to respond to reports of transports carrying Lafayette's troops on the bay.[36] The incident became widely known when Arnold got back to New York, prompting one officer to write, "[Arnold] has hurt himself by discovering too much fondness for cash ... if he is attached to the latter ... he is no acquisition for us."[35]

Arnold's stint in Virginia also demonstrated that he was a target of Patriot wrath and revenge. Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson issued a large reward for his capture, and Washington gave orders to Lafayette to summarily hang Arnold should he be captured.[37] Lafayette had shadowed Arnold and Phillips when they went to Petersburg to join with Cornwallis. After Phillips died, Arnold tried to open communications with the marquis; the letters were returned unopened by Lafayette.[38] Washington wrote to Lafayette, "Your conduct… meets my approbation… in refusing to correspond with Arnold."[39] In conversation with one of Lafayette's officers sent to confer on prisoner exchanges, Arnold is said to have asked what would happen to him should he be captured. The response was, "We should cut off the leg which was wounded in the country's service, and we should hang the rest of you."[39] (The Boot Monument at the Saratoga National Historical Park honors his role there with a representation of his left boot, but it does not name him.)[40]

New London

On his return to New York in June, Arnold made a variety of proposals for continuing to attack economic or military targets (including West Point) in order to force the Americans to end the war. Clinton was not interested in most of his aggressive ideas, but the arrival of 3,000 new Hessian troops led him to relent.[22] He authorized an expedition against the port of New London, Connecticut, near Arnold's childhood home of Norwich. Arnold's force of more than 1,700 men raided and burned New London on September 4, not long after the birth of his second son, and they captured Fort Griswold, causing damage estimated at $500,000.[41] British casualties were high; nearly one quarter of the force sent against Fort Griswold was killed or wounded, a rate at which Clinton claimed he could ill afford more such victories.[42] Arnold only reported 44 killed and 127 wounded in his official report, but there were unofficial whispers that between 400 and 500 casualties had occurred, with at least one claim that it had been like "a Bunker Hill expedition".[43]

The capture of Fort Griswold was followed by the British slaughtering the surviving garrison after the Americans had surrendered. Of a garrison numbering about 150, more than 130 were killed or seriously wounded.[44][45] Stephen Hempstead was one of the American survivors; he stated, "After the massacre, they plundered us of everything we had, and left us literally naked."[46] Hempstead was among the wounded and reported that he was placed on a wagon with others to be taken down to the fleet. The wagon was allowed to run down the hill, where it crashed into a tree, throwing some of the wounded men off the wagon and aggravating their injuries.[46]

Arnold was not in a position to influence what transpired at Fort Griswold, as he remained in New London and observed the action at Fort Griswold across the river. He was blamed by many on both sides for the affair, however, because he was the commanding officer who bore full responsibility for the actions of his men.[44] American sentiments were further inflamed against him for the simple fact that he had betrayed and killed those among whom he had grown up.

Later years

If [Arnold] really felt in his conscience that he had done wrong in siding against his mother country, he should have sheathed his sword and served no more [...] Gladly as I would have paid with my blood and my life for England's success in this war, this man remained so detestable to me that I had to use every effort not to let him perceive, or even feel, the indignation of my soul.

— Hessian Captain Johann Ewald (translation by Joseph Tustin)[47]

Even before the surrender of Cornwallis in October, Arnold had requested permission from Clinton to go to England to give Lord Germain his thoughts on the war in person.[43] When word reached New York of the surrender, Arnold renewed the request, which Clinton then granted. On December 8, 1781, Arnold and his family left New York for England.[48] In London, he aligned himself with the Tories, advising Germain and King George III to renew the fight against the Americans. In the House of Commons, Edmund Burke expressed the hope that the government would not put Arnold "at the head of a part of a British army" lest "the sentiments of true honor, which every British officer [holds] dearer than life, should be afflicted."[49] To Arnold's detriment, the anti-war Whigs had gotten the upper hand in Parliament, and Germain was forced to resign, with the government of Lord North falling not long after.[50]

Arnold then applied to accompany General Carleton, who was going to New York to replace Clinton as commander-in-chief; this request went nowhere.[50] Other attempts failed to gain positions within the government or the British East India Company over the next few years, and he was forced to subsist on the reduced pay of non-wartime service.[51] His reputation also came under criticism in the British press, especially when compared to that of Major André, who was celebrated for his patriotism. One particularly harsh critic said that Arnold was a "mean mercenary, who, having adopted a cause for the sake of plunder, quits it when convicted of that charge."[50] In turning him down for an East India Company posting, George Johnstone wrote, "Although I am satisfied with the purity of your conduct, the generality do not think so. While this is the case, no power in this country could suddenly place you in the situation you aim at under the East India Company."[52]

Arnold saw no further military duty, despite repeated attempts to gain command positions in the British Army or with the British East India Company. He resumed business activities, engaging in trade while based in Saint John, New Brunswick and then London. He died in London in 1801, and was buried without military honors.[53]

Notes

- ↑ Brandt (1994), p. 4–6

- ↑ Flexner (1953), p. 8

- ↑ Flexner (1953), p. 13

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 49–53

- ↑ Brandt (1994), p. 14

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 62

- 1 2 Randall (1990), pp. 78–132

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 131–228

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 228–320

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 318–323

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 262–264

- ↑ Howe (1848), pp. 4–6

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 321–325

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 331–336

- ↑ Martin (1997), pp. 333–405

- ↑ Brandt (1994), pp. 146–170

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 420–448

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 452–582

- ↑ Arnold (1905), pp. 342–348

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 568

- ↑ Fahey

- 1 2 Brandt (1994), p. 249

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 577

- ↑ Brandt (1994), p. 240

- ↑ Brandt (1994), p. 241

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 578–579

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 579

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 582

- ↑ Rose (2006), p. 152

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 582–583

- ↑ Wadell, Joseph (1902). Annals of Augusta County, Virginia, from 1726 to 1871. C. Russell Caldwell. p 278. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=rZbEC1kEdpcC&pg=PA278&lpg=PA278&dq=%22sampson+mathews%22+benedict+arnold&source=bl&ots=ogEYCfX4sU&sig=fnh6UkBocVgPnZQdGyH-K_AIvR8&hl=en&sa=X&ei=AA6cUYyvL4jm9gSauIBw&ved=0CB4Q6AEwAjgK#v=onepage&q=%22sampson%20mathews%22%20benedict%20arnold&f=false

- 1 2 Randall (1990), pp. 584–585

- ↑ Brandt (1994), p. 247

- ↑ Brandt (1994), pp. 247–248

- 1 2 Brandt (1994), p. 248

- ↑ Brandt (1994), p. 246

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 584

- ↑ Unger (2002), p. 140

- 1 2 Unger (2002), p. 141

- ↑ Nelson (2006), p. 400

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 585–591

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 589

- 1 2 Brandt (1994), p. 252

- 1 2 Brandt (1994), pp. 250–252

- ↑ Ward (1952), p. 628

- 1 2 Allyn, p. 53

- ↑ Ewald (1979), p. 296

- ↑ Brandt (1994), p. 253

- ↑ Lomask (1967)

- 1 2 3 Brandt (1994), p. 255

- ↑ Brandt (1994), pp. 257–259

- ↑ Brandt (1994), p. 257

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 592–613

References

- Allyn, Charles (1999) [1882]. Battle of Groton Heights: September 6, 1781. New London: Seaport Autographs. ISBN 978-0-9672626-1-1. OCLC 45702866.

- Arnold, Isaac Newton (1905). The Life of Benedict Arnold: his Patriotism and his Treason. Chicago: A. C. McClurg. OCLC 9993726.

- Brandt, Clare (1994). The Man in the Mirror: A Life of Benedict Arnold. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-40106-7.

- Ewald, Johann (1979). Tustin, Joseph P., ed. Diary of the American War: a Hessian Journal. Tustin, Joseph P.(trans). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02153-4.

- Fahey, Curtis (1983). "Arnold, Benedict". In Halpenny, Francess G. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. V (1801–1820) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Flexner, James Thomas (1953). The Traitor and the Spy: Benedict Arnold and John André. New York: Harcourt Brace. OCLC 426158.

- Lomask, Milton (October 1967). "Benedict Arnold: The Aftermath of Treason". American Heritage Magazine.

- Martin, James Kirby (1997). Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero (An American Warrior Reconsidered). New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-5560-7. (This book is primarily about Arnold's service on the American side in the Revolution, giving overviews of the periods before the war and after he changes sides.)

- Nelson, James L (2006). Benedict Arnold's Navy. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-146806-0. OCLC 255396879.

- Randall, Willard Sterne (1990). Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor. William Morrow and Inc. ISBN 1-55710-034-9.

- Rose, Alexander (2006). Washington's Spies: the Story of America's First Spy Ring. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-553-80421-8. OCLC 150181912.

- Unger, Harlow G (2002). Lafayette. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-39432-7. OCLC 186158241.

- Ward, Christopher (1952). The War of the Revolution. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 214962727.