Cantabrian dialect

| Cantabrian | |

|---|---|

| Cántabru, montañés | |

| Native to | Spain |

| Region | Autonomous community of Cantabria and Asturian municipalities of Peñamellera Alta, Peñamellera Baja and Ribadedeva.[1] |

Native speakers | 3,000 (2011) |

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Cantabrian (cántabru, in Cantabrian) is a group of dialects belonging to Astur-Leonese. It is indigenous to the territories in and surrounding the Autonomous Community of Cantabria, in Northern Spain.

Traditionally, some dialects of this group have been further grouped by the name Montañés (that is, from the Mountain), being "La Montaña" (the Mountain) a traditional name for Cantabria due to its mountainous orography.

Distribution

These dialects belong to the Northwestern Iberian dialect continuum, and have been classified as belonging to the Astur-Leonese domain by successive research works carried out through the 20th century, the first of them, the famous work El dialecto Leonés, by Menéndez Pidal.[2]

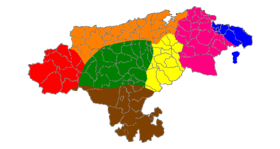

This dialect group spans the whole territory of Cantabria. In addition, there is historical evidence of traits (such as toponyms, or certain constructions) linking the speech of some nearby areas to the Cantabrian Astur-Leonese group:

- The western part of Las Encartaciones, in Biscay.

- Bordering areas with Burgos: especially the upper valleys of Espinosa de los Monteros, where Pasiegu dialect was spoken.

- Bordering areas with Palencia

- Valleys of Peñamellera and Ribadedeva, in the westernmost part of Asturias.

Some of this areas had historically been linked to Cantabria before the 1833 territorial division of Spain, and the creation of the Province of Santander (with the same territory as modern-day's Autonomous Community).

Dialects

Based on the location on where dialects are spoken, we find a Traditional dialectal division of Cantabria, which normally correspondonds to the different valleys or territories:

| Autoglottonym | Area of usage | Meaning of name |

|---|---|---|

| Montañés | La Montaña, i.e. Coastal and Western parts of Cantabria | relative or belonging to the people of La Montaña |

| Pasiegu | Pas, Pisueña and upper Miera valleys | relative or belonging to the people of Pas |

| Pejín | Western Coastal Villages | from peje, fish. |

| Pejinu | Eastern Coastal Villages | from peji, fish. |

| Tudancu | Tudanca | relative or belonging to the people of Tudanca |

However, based on linguistic evidence, R. Molleda proposed what is today the habitual division of dialectal areas in Cantabria. Molleda proposed to take the isogloss of the masculine plural gender morphology, which seems to surround a large portion of Eastern Cantabria, running from the mouth of the Besaya River in the North, and along the Pas-Besaya watershed. He then proceeded to name the resulting areas Western and Eastern, depending on the location to the West or East of the isogloss. This division has gained strength due to the fact that, even though masculine morphology is not a very important difference, many other isoglosses draw the same line.

Linguistic description

There are some features in common with Spanish, the main of which is the set of consonants which is nearly identical to that of Northern Iberian Spanish. The only important difference is preservation of the voiceless glottal fricative (/h/) as an evolution of Latin's word initial f- as well as the [x-h] mergers; both feature are common in many Spanish dialects, especially those from Southern Spain and parts of Latin America.

The preservation of the voiceless glottal fricative was usual in Middle Spanish, before the /h/ in words like /humo/, from Latin fumus, resulted in Modern Spanish /umo/. Every Cantabrian dialect keeps /f/ before consonants such as in /'fɾi.u/ (cold), just as Spanish and Astur-Leonese do.

| Feature | Western Dialects | Eastern Dialects | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Valleys | Inner Valleys | |||

| f+C | /f/ /'fɾi.u/ |

frigĭdus cold | ||

| f+w | /h/ /'hue.gu/ |

/f/ /'fue.gu/ |

/f/ or /x/ /'hue.gu/ or /'xue.gu/ |

focus hearth, later fire |

| f+j | /h/ /'hie.ru/ |

Ø /'ie.ru/ |

ferrum iron | |

| f+V | /h/ /ha'θeɾ/ |

Ø /a'θeɾ/ |

facĕre to do (verb) | |

The [x - h] merger is typical in most Western and Eastern Coastal dialects, where [x] merges into [h]. However, the Eastern dialects from the Inner Valleys have merged [h] into [x]; moreover, there are older speakers that lack any kind of merger, fully distinguishing the minimal pair /huegu/ - /xuegu/ (fire - game).

| Western dialects | Eastern dialects | Gloss | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coastal Valleys | Inner Valleys | ||

| [h] ['hue.ɣ̞u] |

[h] ['hue.ɣ̞u] |

no, or [x] ['xue.ɣ̞u] |

iocus joke, later game |

Other features are common to most Astur-Leonese dialects; some of these are:

- Use of /u/ as masculine singular gender morpheme: most dialects use a closed central rounded vowel [ʉ], as masculine morpheme, although only eastern dialects have shown [ʉ] - [u] contrast.

- Opposition between singular and plural masculine gender morphemes. The dialectal boundaries of this feature are usually used to represent the western and eastern dialects:

- Western Dialects oppose /u/ masculine singular marker to /os/ masculine plural marker. E.g. perru (dog) but perros (dogs).

- Eastern Dialects used to oppose /ʉ/+metaphony (masc. sing.) to /us/ (masc. plural). E.g. pirru ['pɨ.rʉ] (dog) but perrus (dogs). This opposition is nearly lost and only few speakers of the Pasiegu dialect still use it. Nowadays, the most common situation is the no-opposition, using /u/ as a masculine morpheme both in singular and plural.

- Mass neuter: this feature marks uncountableness in nouns, pronouns, articles, adjectives and quantifiers. As in general Astur-Leonese, the neuter morpheme is /o/, rendering an opposition between pelo (the hair) and pelu (one strand of hair), however the actual development of this feature changes from dialect to dialect:

- Most western dialects have recently lost this distinction in nominal and adjectival morphology, merging masculine and neuter morphology (pelu for both previous examples), although keeping this distinction in pronouns, quantifiers and articles, so lo (it, neuter) would refer to pelu (the hair, uncountable), but lu (it, masculine) would refer to 'pelu (hair strand, countable).

- Eastern dialects show a more complex behaviour, with vowel harmony as the main mechanism for neuter distinction. Due to this, word-final morphology was not so important, and the mutations in stressed and previous syllables play a more important role. Thus, these would have ['pɨ.lʉ] (strand of hair, countable) and ['pe.lu] (the hair, uncountable), the same applied for adjectives. Likewise, eastern dialects modified their pronoun systems in order to avoid misunderstandings, replacing lu with li (originally dative pronoun) as third person singular accusative pronoun, and using lu for mass neuter. However, this distinction has been gradually lost and is now only retained in some older speakers of Pasiegu dialect. A unique feature of these dialects is the use of feminine agreeing quantifiers with neuter nouns, such as: mucha pelu (lots of hair).

- Dropping of the -r from verb infinitives when clitic pronouns are appended. This results in cantar (to sing) +la (it, feminine) = cantala.

- Preference of simple verbal tenses over complex (compound) tenses, e.g. "ya acabé" (I already finished) rather than "ya he acabáu" (I have already finished).

Threats and Recognition

In 2009, Cantabrian was listed as a dialect of the Astur-Leonese language by UNESCO's Red Book of the World’s Languages in Danger, which was in turn classified as a definitely endangered language.[3]

Comparative tables

| West. Cantabrian | East. Cantabrian | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gloss | Latin | Asturian | Montañés | Pasiegu | Castilian Spanish | Features |

| "high" | ALTUM | altu | altu | altu | alto | ALTUM > altu |

| "to fall" | CADĔRE [A] | cayer | cayer | cayer | caer | Before short e, /d/ → /y/. |

| "to say" | DĪCERE | dicir | dicir/icir | dicir/dicer/icir | decir | Conjugation shift -ERE → -IR |

| "to do" | FACERE | facer/facere | jacer [D] | hacer [D] | hacer | Western /f/→[h]. Eastern /f/→∅. |

| "iron" | FERRUM | fierro | jierru | yerru | hierro | Western /ferum/ > [hjeru]. Eastern /ferum/ > [hjeru] > [jeru] > [ʝeru]. |

| "flame" | FLAMMAM | llama | llapa [F] | llama [G] | llama | Palatalization /FL-/ > /ʎ/ (or /j/, due to western yeismo) |

| "fire" | FOCUM | fueu/fuegu | jueu | juigu/juegu [C] | fuego | Western: FOCUM > [huecu] > [huegu] > [hueu]. Eastern: FOCUM > [xuecu] > [xuegu]/[xuigu] (metaphony). |

| "fireplace" | LĀR | llar | llar [F] | lar [H] | lar | Western: Palatalization of ll-, yeísmo. |

| "to read" | LEGERE | lleer | leer | leyer [A] | leer | Eastern: pervivence of -g- as -y-. |

| "loin" | LUMBUM [B] | llombu | lombu/llombu | lumu/lomu [C] | lomo | Western: conservatino of -MB- group. Eastern: metaphony. |

| "mother" | MATREM | madre/ma | madre | madri | madre | Eastern: closing of final final -e. |

| "blackbird" | MIRULUM | mierbu | miruellu | miruilu [C] | mirlo | Westen: palatalization of -l-. Eastern: metaphony. |

| "to show" | MOSTRARE | amosar | amostrar [E] | mostrar | mostrar | Western: prothesis. |

| "knot" | *NODUS | ñudu | ñudu | ñudu | nudo | Palatalization of Latin N- |

| "ours" | NOSTRUM | nuestru/nuesu | nuestru | muistru [C] | nuestro | Eastern: metaphony and confusion between Latin pronoun nos and 1st person plural ending -mos. |

| "cough" | TUSSEM | tus | tus | tus | tos | |

| "almost" | QUASI | cuasi | cuasi | casi | casi | |

| "to bring" | TRAHĔRE[A] | trayer | trayer | trayer | traer | Conservation of Latin -h- by -y-. |

| "to see" | VIDĒRE | ver | veer | veyer [A] | ver | Eastern: before short e, /d/ → /y/. |

| West. Cantabrian | East. Cantabrian | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gloss | Latin | Asturian | Montañés | Pasiegu | Castilian Spanish | Features |

| "photo" | -- | foto | jotu | afutu [C][E] | foto | Western shows [f] > [h], while Eastrn prefers prothesis. |

| "dog/dogs" | -- | perru/perros | perru/perros | pirru/perrus [C] | perro/perros | Western masculine singular -u, plural -os. Eastern masculine singular -u + metaphony, plural -us. |

The following notes only apply for the Cantabrian derivatives, but might as well occur in other Astur-Leonese varieties:

- A Many verbs keep the etymological -h- or -d- as an internal -y-. This derivation is most intense in the Pasiegan Dialect.

- B Latin -MB- group is only retained in the derivatives of a group containing few, but very used, Latin etyma: lumbum (loin), camba (bed), lambere (lick), etc. however, it has not been retained during other more recent word derivations, such as tamién (also), which comes from the -mb- reduction of también a compound of tan (as) and bien (well).

- C In Pasiegan dialect, all masculine singular nouns, adjectives and some adverbs retain an ancient vowel mutation called Metaphony, thus: lumu (one piece of loin) but lomu (uncountable, loin meat), the same applies for juigu (a fire/campfire) and juegu (fire, uncountable) and muistru and muestru (our, masculine singular and uncountable, respectively).

- D Most Western Cantabrian Dialects retain the ancient initial F- as an aspiration (IPA [h]), so: FACERE > /haθer/. This feature is still productive for all etyma starting with [f]. An example of this is the Greek root phōs (light) which, through Spanish foto (photo) derives in jotu (IPA: [hotu])(photography).

- D All Eastern Dialects have mostly lost Latin initial F-, and only keep it on certain lexicalized vestiges, such as: jumu (IPA: [xumu]). Thus: FACERE > /aθer/.

- E Prothesis: some words derive from the addition of an extra letter (usually /a/) at the beginning of the word. arradiu, amotu/amutu, afutu.

- F Yeísmo: Most Cantabrian dialects do not distinguish between the /ʝ/ (written y) and /ʎ/ (written ll) fonemes, executing both with a single sound [ʝ]. Thus, rendering poyu and pullu (stone seat and chicken, respectively) homophones.

- G Lleísmo: Pasiegan Dialect is one of the few Cantabrian Dialects which does distinguish /ʝ/ and /ʎ/. Thus, puyu and pullu (stone seat and chicken, respectively) are both written and pronounced differently.

- H Palatalization: Cantabrian Dialects do mostly not palatalize Latin L-, however, some vestiges might be found in Eastern Cantabrian Dialects, in areas bordering Asturias (Asturian a very palatalizing language). This vestiges are often camuflated due to the strong Yeísmo. Palatalization of Latin N- is more common, and words such as ñudu (from Latin nudus), or ñublu (from Latin nubĭlus) are more common.

Sample text

Central Cantabrian

Na, que entornemos, y yo apaecí esturunciau y con unos calambrios que me jiendían de temblíos... El rodal quedó allá lantón escascajau del too; las trichorias y estadojos, triscaos... Pero encontó, casi agraecí el testarazu, pues las mis novillucas, que dispués de la estorregá debían haber quedau soterrás, cuasi no se mancaron. ¡Total: unas lijaduras de poco más de na![4]

Castilian

Nada, que volcamos, y yo acabé por los suelos y con unos calambres que me invadían de temblores...El eje quedó allá lejos totalmente despedazado; las estacas quebradas... Pero aún así, casi agradecí el cabezazo, pues mis novillas, que después de la caída deberían haber quedado para enterrar, casi no se lastimaron. ¡Total: unas rozaduras de nada!

Footnotes

- ↑ El asturiano oriental. Boletín Lletres Asturianes nº7 p44-56 Archived December 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Menéndez Pidal, R (2006) [1906]. El dialecto Leonés. León: El Buho Viajero. ISBN 84-933781-6-X.

- ↑ UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger Archived February 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., where Cantabria is listed as a dialect of the Astur-Leonese language.

- ↑ Extracted from Relato de un valdiguñés sobre un despeño García Lomas, A.: El lenguaje popular de la Cantabria montañesa. Santander: Estvdio, 1999. ISBN 84-87934-76-5

References

- García Lomas, A.: El lenguaje popular de la Cantabria montañesa. Santander: Estvdio, 1999. ISBN 84-87934-76-5

External links

- Cantabrian-Spanish Dictionary in the Asturian wiktionary (in Cantabrian).

- Alcuentros, Cantabrian magazine of minority languages (in Cantabrian/Castilian)

- Proyeutu Depriendi Distance learning of Cantabrian (in Cantabrian/Castilian)