Original Town of Fernandina Historic Site

|

Original Town of Fernandina Historic Site | |

|

Plaza San Carlos marker at original Fernandina town site | |

| Location | Fernandina Beach, Florida |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 30°41′19″N 81°27′18″W / 30.68861°N 81.45500°WCoordinates: 30°41′19″N 81°27′18″W / 30.68861°N 81.45500°W |

| Built | 1811 |

| NRHP Reference # | 86003685[1] |

| Added to NRHP | January 29, 1990 |

.jpg)

The Original Town of Fernandina Historic Site, also known as "Old Town", is a historic site in Fernandina Beach, Florida, located on Amelia Island. It is roughly bounded by Towngate Street, Bosque Bello Cemetery, Nassau, Marine, and Ladies Streets. On January 29, 1990, it was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as a historic site. Lying north of the Fernandina Beach Historic District, it is accessible from North 14th Street.

Prior to the arrival of Europeans on what is now Amelia Island, the Old Town site was home to Native Americans. The French, English, and Spanish all maintained a presence on Amelia Island at various times during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, but the Spanish established Fernandina. Old Town, the original location of the town of Fernandina, has the distinction of being the last Spanish city platted in the Western Hemisphere, in 1811. The plat is based on the 1573 Law of the Indies, a document utilized by the Spanish to organize new towns established during their explorations.

The area within Old Town known as Plaza San Carlos was the plaza ground in front of the Spanish Fort San Carlos, which is no longer in existence. Today the Plaza San Carlos is maintained by the State of Florida as part of the State Park System. The plaza offers a space for nature study and picnicking.

David Levy Yulee, one of the first United States senators from Florida, established the first cross-state railroad running from Fernandina Beach to Cedar Key, which opened on March 1, 1861. When Yulee established the railroad, he platted “new” Fernandina, shifting the town of Fernandina from Old Town to the location along Centre Street. As a result of this shift, Old Town has become primarily a residential neighborhood.

The field work and scholarship of archeologists and historians in the last forty years has advanced our understanding of the area's Native American history after European contact. The human occupation of present-day Old Town began around three thousand years ago, and some of the most colorful episodes of Florida history occurred here. Local government has come to realize the special place Old Town has in telling the story of Fernandina’s heritage, and in 1989 the city of Fernandina Beach passed a historic preservation ordinance to protect the district by establishing local boundaries. Old Town has design guidelines for rehabilitation and construction projects, reviewed by the city’s Historic District Council. The Old Town preservation and development guidelines focus on lot orientation, an integral part of the process of preserving the 1811 Spanish plan. Building aesthetics are also taken into account. The Old Town Historic District was last surveyed as part of the city’s 1985 Historic Resources survey.

Old Town celebrated the 200th anniversary of its founding on April 2, 2011.

History

Native American campsite to British garrison

The original town of Fernandina was established on a bluff over the Amelia River at the northwest end of Amelia Island in northernmost Florida on the east coast of the United States. Native Americans had camped on this land above the Amelia River from 2000–1000 BC.[2] The St. Johns People dwelt here from as early as 1000 B.C. and their Timucua descendants encamped in the same area.

The naturally deep and protected harbor was known to the early European explorers of Florida. The island was called Napoyca by the Timucua and was associated with the name "Santa María" from the early First Spanish Period (1500–1763).[3] Spanish Franciscan friars established the fortified mission compound of Santa María de Sena by 1602[3] near this place, which was only a league (3 miles) away from the mission of San Pedro de Mocama[4] on present-day Cumberland Island. A Spanish sentinel house was built here in 1696. In later colonial times the site gained military importance because of its deep harbor and its strategic location near the northern boundary of Spanish Florida. During his invasion of north Florida, 1736–1742, the governor of the British colony of Georgia, James Oglethorpe, stationed a military guard of Scottish Highlanders on the site and named the island after Princess Amelia, the daughter of King George II of Great Britain.

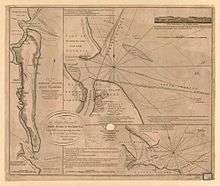

"New Settlement"

Oglethorpe withdrew his troops in 1742, and the area became a buffer zone between the English and Spanish colonies until the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, when Spain traded Florida to Great Britain for control of Havana, Cuba. During the early period of British rule, the island was known as Egmont Isle, after Lord Egmont who had a 10,000 acre estate there, almost the entire island. The so-called “New Settlement” (present-day Old Town), on the south side of the mouth of Egan’s Creek adjoining the Amelia River, was presumably its headquarters.[5] A map of the new settlement shown in charts drawn by Capt. John Fuller and then mapped by cartographer Thomas Jefferys in 1770 depicts houses and streets laid out from "Anderson's Creek" (present-day Egan's Creek) south toward Morriss Bluff. Egmont had only recently begun his development of the island in 1770 when Gerard de Brahm prepared his map, the "Plan of Amelia, Now Egmont Island", which depicted most of the planned development at the north end. Egmont died in December 1770, whereupon his widow, Lady Egmont, assumed control of his vast Florida estates. She persisted in development of the plantation and made Stephen Egan her agent to manage it. He was able to grow profitable indigo crops there[6] until it was destroyed by rebel troops from Georgia in 1776.[7]

In the late 1770s and early 1780s, British loyalists fleeing Charleston and Savannah hastily erected new buildings at the settlement, calling their impromptu town Hillsborough. When Spain regained possession of Florida in 1783, the Amelia harbor served as an embarkation point for loyalists abandoning the colony who tore down the buildings and took the lumber with them. In June 1785, former British governor Patrick Tonyn moved his command to Hillsborough town, from whence he sailed to England later that year.[8][9]

After the British evacuation, Mary Mattair, her children, and a farmhand were the sole occupants left on Amelia island. She had received a grant from Governor Tonyn of the property on the bluff overlooking the Amelia River. Following the exchange of flags in 1784, the Spanish Crown allowed Mattair to remain on the island. In trade for the earlier British grant,[2] the Spanish authorities awarded her 150 acres within the present-day city limits of Fernandina Beach. The site of Mattair's initial grant is today's Old Town Fernandina.[10]

In December 1793, Mary Mattair's daughter Maria married Domingo Fernandez. Fernandez had arrived in St. Augustine from Galicia, Spain about 1786. He worked for the Spanish government as captain of a gunboat and a harbor pilot at Amelia Island until 1800, when he retired to become a full-time planter.[11]

In June 1795, American rebel marauders led by Richard Lang attacked the Spanish garrison on Amelia Island. Colonel Charles Howard, an officer in the Spanish military, discovered that the rebels had built a battery and were flying the French flag. On August 2, he raised a sizable Spanish force, sailed up Sisters Creek and the Nassau River, and attacked them. The rebels fled across the St. Marys to Georgia.[12]

The passage of the U.S. Embargo Act of 1807, which closed all United States ports to trade with Europe, and the abolition of the American slave trade, made the town a haven for smuggling slaves, liquor and foreign luxury goods. Situated on a peninsula, it was defended by two blockhouses and a detachment of soldiers surrounding the settlement.[13]

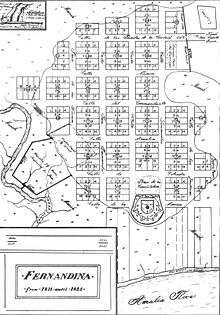

Fernandina Township Platted According to the Laws of the Indies

On January 1, 1811, the town of Fernandina, which was about a mile from the present city, was named in honor of King Ferdinand VII of Spain by the governor of the Spanish province of East Florida, Enrique White. On May 10, 1811,[14] White's successor and acting governor at the time, Juan José Estrada, instructed the newly appointed Surveyor General, George J. F. Clarke, to plat the township[15] in accordance with the 1542 Spanish Laws of the Indies (Leyes de Indias). These laws regulated how the site for a Spanish settlement should be selected, and how the town should be laid out in classical grid form.[16] Places were designated for the fort, the parade ground, the church, and the cemetery. A plaza, originally called Plaza de la Constitution, was set close to the river, one side facing westward to the parade grounds.

Fernandina was the last town platted under the Laws of the Indies in the Western hemisphere and was intended as a bulwark against U.S. territorial expansion. In the following years it was captured and recaptured by a succession of renegades and privateers. Meanwhile, saloons and bordellos proliferated in the booming new township.

Patriots' War

Because it was a center for smuggling and represented a threat to trade of the United States, Fernandina was invaded and seized by forces under the command of General George Mathews in 1812 with the clandestine approval of President James Madison.[17] Mathews and Colonel John McKee were commissioned as secret agents[18] to incite a revolution in Spanish East Florida.[19] A group of Americans calling themselves the "Patriots of Amelia Island" had banded together to drive out the Spanish and reported to General Mathews, who moved into a house at St. Marys, Georgia, just nine miles[20] across Cumberland Sound. Most of the Patriots' force consisted of Georgia militiamen, and wood-choppers and boatmen from the neighborhood of St. Marys.[21] They were supported by slave-holding planters who wanted to stop raiding parties of Seminole Indians from the Alachua region and feared the presence of armed free black militias in Spanish Florida.[22][23]

By March 5, Patriot leader and wealthy Florida planter John Houstoun McIntosh claimed that the Patriots had successfully subjugated the area between the St. Marys and the St. Johns Rivers, and were planning next to take Amelia Island.[24] On March 16, nine American gunboats under the command of Commodore Hugh Campbell formed a line in the harbor and aimed their guns at the town.[25][26] General Mathews, still ensconced at Point Peter on the St. Marys in Georgia, ordered Colonel Lodowick Ashley to send a flag to Don Justo Lopez,[23] commandant of the fort and Amelia Island, and demand his surrender. Lopez acknowledged the superior force and surrendered the port and the town. On March 17 John H. McIntosh, George J. F. Clarke, Justo Lopez, and others signed the articles of capitulation;[27] the Patriots then raised their own standard. The next day, a detachment of 250 regular United States troops were brought over from Point Peter, and the newly constituted Patriot government surrendered the town to General Matthews, who had the stars and stripes of the U.S. flag raised immediately.[28] The Patriots had held Fernandina for only twenty-four hours before turning authority over to the U.S. military.

General Mathews and President Madison had conceived a plan to annex East Florida to the United States, but Congress became alarmed at the possibility of being drawn into war with Spain, and the effort fell apart when Secretary of State James Monroe was forced to relieve Matthews of his commission. Negotiations began for the withdrawal of U.S. troops early in 1813. On May 6, the army lowered the flag at Fernandina and crossed the St. Marys River to Georgia with the remaining troops.[29] Spain took possession of the redoubt and regained control of the island. The Spanish completed construction of the new Fort San Carlos to guard the port side of Fernandina in 1816.

Fort San Carlos was built to protect the strategic harbor of the Amelia River and Spanish interests in northern Florida. The fort was made of wood and earthworks and was armed with eight[30] or ten guns. The town contained about six hundred inhabitants, and its population was rapidly increasing. The former Indian campsite had become the fort’s parade grounds fronting Estrada Street, which still exists—the layout of the original town has been preserved to this day.

Gregor MacGregor and the Republic of the Floridas

Fernandina became increasingly vulnerable to foreign depredations as Spain’s American empire disintegrated. A Scottish military adventurer and mercenary, Gregor MacGregor, claimed to be commissioned by representatives of the revolting South American countries to liberate Florida from Spanish rule.[31] Financed by American backers,[32] he led an army of only 150 men including recruits from Charleston and Savannah, some War of 1812 veterans, and 55 musketeers in an assault on Fort San Carlos. Through spies within the Spanish garrison, MacGregor had learned that the force there consisted of only 55 regulars and 50 militia men. He spread rumors in the town which eventually reached the ear of the garrison commander that an army of more than 1,000 men was about to attack. On June 29, 1817, he advanced on the fort, deploying his men in small groups coming from various directions to give the impression of a larger force.[33] The commander, Francisco Morales, struck the Spanish flag and fled.[34] MacGregor raised his flag, the "Green Cross of Florida", a green cross on a white ground, over the fort[35] and proclaimed the "Republic of the Floridas".[36]

Now in possession of the town, and seeing the need to make the appearance of a legitimate government, MacGregor quickly formed a committee to draft a constitution,[37] and appointed Ruggles Hubbard, the former high sheriff of New York City, as unofficial civil governor, and Jared Irwin, an adventurer and former Pennsylvania Congressman, as his treasurer. MacGregor then opened a post office, ordered a printing press to publish a newspaper, and issued currency to pay his troops and to settle government debts.[38][39] Expecting reinforcements for a raid against the Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine,[40] MacGregor intended to subdue all of Spanish East Florida.[41][42] His plan was doomed to fail, however, as President James Monroe was in sensitive negotiations with Spain to acquire all of Florida.[43]

Soon MacGregor's reserves were depleted, and the Republic needed revenue. He commissioned privateers to seize Spanish ships[44][45] and set up an admiralty court[38][46][47] which levied a customs duty on their sales.[48] They began selling captured prizes and their cargoes, which often included slaves.[49] When about August 28 fellow conspirator Ruggles Hubbard sailed into the harbor aboard his own brig Morgiana, flying the flag of Buenos Ayres, but without the needed men, guns, and money, MacGregor announced his departure.[50] On September 4, faced with the threat of a Spanish reprisal, and still lacking money and adequate reinforcements, he abandoned his plans to conquer Florida and departed Fernandina with most of his officers, leaving a small detachment of men at Fort San Carlos to defend the island.[51] After his withdrawal, these and a force of American irregulars organized by Hubbard and Irwin repelled the Spanish attempt to reassert authority.

Battle of Amelia Island

On September 13 the Battle of Amelia Island commenced when the Spaniards erected a battery of four brass cannons on McLure’s Hill east of the fort. With about 300 men, supported by two gunboats, they shelled Fernandina being held by Jared Irwin. His “Republic of Florida” forces included ninety-four men, the privateer ships Morgiana and St. Joseph, and the armed schooner Jupiter. Spanish gunboats began firing at 3:30 pm and the battery on the hill joined the cannonade. The guns of Fort San Carlos, on the river bluff northwest of the hill, and those of the St. Joseph defended Amelia Island. Cannonballs killed two and wounded other Spanish troops clustered below. Firing continued until dark. The Spanish commander, convinced he could not capture the island, then withdrew his forces.[51][52]

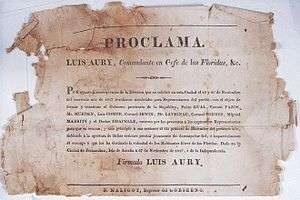

French corsair Louis Aury

Before he left Florida, MacGregor had met with the French privateer, Louis Aury, a previous acquaintance from political intrigues in South America who had served with him in Simon Bolívar's army in New Granada.[53] As MacGregor was going out of the harbor of Fernandina on the privateer Freeman Johnson's vessel, Aury was coming in on his flagship, Mexican Congress. Visits were exchanged, and Aury entertained the Scotsman aboard his schooner,[54] anchored outside the bar of the inlet. Aury was accompanied by two other privateering ships and held prizes valued at $60,000.[55] Thus briefed on the state of affairs in Fernandina, he sailed into the port on September 17, 1817, with a crew of 300 American recruits and Haitian ex-slaves, free blacks, and mulattoes known as "Aury’s blacks". His principal lieutenant was Joseph Savary, a mulatto refugee from the Haitian revolution and veteran of the defense of New Orleans in 1815.[56]

Aury marched to Hubbard’s quarters with a body of armed men and demanded concessions from Hubbard and Irwin, who were short of troops and bereft of funds. They appealed for financial aid, but Aury refused, unless he have supreme command of both civil and military government. When Hubbard and Irwin protested his terms, Aury threatened to leave the island. Realizing they had nothing to gain by opposing him, a compromise was reached and they made an alliance with the Frenchman:[57] Aury would be commander-in-chief of military and naval forces, Irwin his adjutant general, and Hubbard the civil governor of Amelia.[58] The flag of the revolutionary Republic of Mexico would be raised over Fort San Carlos. Thus Amelia Island was dubiously annexed to the Republic of Mexico on September 21, 1817.[59]

Adams-Onis Treaty transfers Florida to the United States

The new government of Fernandina was short-lived. According to Lloyd's of London, Aury's commissioned privateers captured more than $500,000 worth of Spanish goods in two months.[60] They preyed on Spanish vessels carrying slaves, most of whom were smuggled into Georgia after being captured.[61] These activities threatened the negotiations concerning the cession of Florida and in response President Monroe sent forces to retake Amelia on October 31. After a contentious exchange of communications with representatives of the president,[62][63] Aury realized his position was untenable and surrendered the island to Commodore J.D. Henley and Major James Bankhead on December 23, 1817.[64] Aury remained over two months as an unwelcome guest; Bankhead occupied Fernandina and held it "in trust" for Spain.[65] Although angered by U.S. interference at Fort San Carlos, Spain did cede Florida in 1821. The proclamation of the Adams-Onis Treaty on February 22, 1821, two years after its signing, officially transferred East Florida and what remained of West Florida to the United States.[66] The U.S. Army made little use of the fort and soon abandoned it.

Town of Fernandina moves

In 1853 the town of Fernandina moved about a mile further south when David Levy Yulee chartered his Florida Railroad line, the first cross-state railroad in Florida. Fernandina was to be the eastern terminus, but Yulee declared the rails could not cross the salt-marsh to Old Town; in fact, the land area of Old Town was insufficient to support Yulee's vision of 'Manhattan of the South'. His company began construction in 1855, and the original site of Fernandina, the one-time smugglers’ den and freebooter haven, lapsed into quiet obscurity. The original Spanish town plan and regular street grid, with many of the Spanish street names, remain.

During the American Civil War, the local militia of the Confederate Army occupied Fort San Carlos.

Archaeologists estimate that two-thirds of the area formerly occupied by Fort San Carlos has disappeared through erosion[67] by the Amelia River. Traces of earthworks and the former parade grounds can be found along Estrada Street.[68]

Notes

- ↑ "National Register of Historical Places - Florida (FL), Nassau County". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2007-03-31.

- 1 2 "Fernandina Plaza Historic State Park" (PDF). State of Florida Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks. March 10, 2004. p. 11. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- 1 2 Thomas 1987, p.165.

- ↑ Bonnie Gair McEwan (1993). The Spanish missions of La Florida. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1232-2. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ William Bartram (1958). The Travels of William Bartram. University of Georgia Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-8203-2027-4. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ Joyce E. Chalpin (1996). An Anxious Pursuit: Agricultural Innovation and Modernity in the Lower South, 1730-1815. UNC Press Books. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8078-4613-1. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- ↑ Perceval 1812

- ↑ Bland and Associates. "Appendix A: Historic Context and References". Historic Properties Resurvey, City of Fernandina Beach, Nassau County, FL. p. 4.

- ↑ James Grant Forbes (1821). Sketches, historical and topographical, of the Floridas, more particularly of East Florida. p. 54. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ Bland and Associates. "Appendix A: Historic Context and References". Historic Properties Resurvey, City of Fernandina Beach, Nassau County, FL. p. 7.

- ↑ "Domingo Fernandez". East Florida Herald. 19 September 1833.

- ↑ O'Riordan, Cormac A (1995). "The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida". Paper 99, Theses and Dissertations. University of North Florida. p. 13. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- ↑ A. M. De Quesada (30 August 2006). A History of Florida Forts: Florida's Lonely Outposts. The History Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-59629-104-1. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ Louise Biles Hill (1941). "George J. F. Clarke, 1774-1836". Florida Historical Quarterly. 21 (3 ed.). Florida Historical Society. p. 214. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ↑ United States. Congress. House. House Documents, Otherwise Publ. as Executive Documents: 13th Congress, 2d Session-49th Congress, 1st Session. p. 20.

- ↑ James G. Cusick (15 April 2007). The Other War of 1812: The Patriot War and the American Invasion of Spanish East Florida. University of Georgia Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8203-2921-5. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ↑ Writers' Program (Fla.) (1940). Seeing Fernandina: A Guide to the City and Its Industries. Fernandina News Publishing Company. p. 23. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ↑ United States. Congress (1858). "Robert Harrison". Congressional edition. U.S. G.P.O. p. 43. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ Cusick 2007, p. 2

- ↑ Frank Marotti (5 April 2012). The Cana Sanctuary: History, Diplomacy, and Black Catholic Marriage in Antebellum St. Augustine, Florida. University of Alabama Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8173-1747-8. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ Williams 1837, p.193

- ↑ Cusick 2003, p.49

- 1 2 Williams 1837, p.194

- ↑ Writers 1940, p. 25

- ↑ Congressional edition 1858, p.45

- ↑ David S. Heidler; Jeanne T. Heidler (2004). Encyclopedia of the War Of 1812. Naval Institute Press. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-59114-362-8. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ John Lee Williams (1837). The Territory of Florida: Or Sketches of the Topography, Civil and Natural History, of the Country, the Climate, and the Indian Tribes, from the First Discovery to the Present Time. A. T. Goodrich. p. 195. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Congress 1858, p. 45

- ↑ T. Frederick Davis (1930). United States Troops in Spanish East Florida, 1812-1813. Part 5. Florida Historical Society. p. 34. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Niles' Weekly Register. 1818. p. 190.

- ↑ British and Foreign State Papers. H.M. Stationery Office. 1837. p. 789.

- ↑ Frank L. Owsley, Jr. (1997). Filibusters and expansionists: Jeffersonian manifest destiny, 1800-1821. University of Alabama Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-8173-0880-3. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Owsley and Smith 1997, p.127

- ↑ Writers 1940, p.27

- ↑ Junius Elmore Dovell (1952). Florida: Historic, Dramatic, Contemporary. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. p. 199. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ John Quincy Adams (1916). Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed. Writings of John Quincy Adams. 6. Macmillan. p. 285. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Floridas (Republic) (1942). Republic of the Floridas: Constitution and Frame of Government Drafted by a Committee Appointed by the Assembly of Representatives, and Submitted at Fernandina, December 9, 1817. Priv. print. Douglas Crawford McMurtrie. pp. 1–5. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- 1 2 Owsley and Smith 1997, p.128

- ↑ Narrative of a Voyage to the Spanish Main: In the Ship "Two Friends"; the Occupation of Amelia Island. John Miller. 1819. p. 91. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ "McGregor is unlikely to succeed in reducing St. Augustine". Connecticut Courant, Hartford, CT. August 12, 1817. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ↑ John Quincy Adams (1875). Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: comprising portions of his diary from 1795 to 1848. J.B. Lippincott & Co. p. 50. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ Great Britain 1837, p.763

- ↑ Niles 1818, p.303

- ↑ State Papers and Publick Documents of the United States from the Accession of George Washington to the Presidency, Exhibiting a Complete View of Our Foreign Relations Since that Time: (1789-1818). 12 (3 ed.). 1819. p. 422. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ Great Britain 1837, p.769

- ↑ Adams 1875, p. 75

- ↑ Niles 1818, p.339

- ↑ Miller 1819, p.89

- ↑ Jane G. Landers (1 June 2010). Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolutions. Harvard University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-674-05416-5. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ Davis, T. Frederick (July 1928). "MacGregor's Invasion of Florida, 1817". Florida Historical Society Quarterly. 7 (1): 25. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- 1 2 William S. Coker; Jerrell H. Shofner (1991). Florida: From the Beginning to 1992 : a Columbus Jubilee Commemorative. Houston, Texas: Pioneer Publications. p. 7. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ↑ Owsley and Smith 1997, p.134

- ↑ Adams 1875, p.75

- ↑ Foreign and Commonwealth Office 1837, p. 771

- ↑ Miller 1819, p.95

- ↑ Owsley and Smith 1997, p.138

- ↑ Niles 1818, p.302

- ↑ Owsley and Smith 1997, p.138.

- ↑ State papers, 1819, p.401

- ↑ John Wymond; Henry Plauché Dart (1941). The Louisiana Historical Quarterly. Louisiana Historical Society. p. 645. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ↑ Owsley and Smith 1997, p.139

- ↑ Niles 1818, p.347-352

- ↑ United States. President; United States. Dept. of State (1819). State papers and publick documents of the United States, from the accession of George Washington to the presidency: exhibiting a complete view of our foreign relations since that time ... 11 (3 ed.). Printed and published by Thomas B. Wait. pp. 382–410. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ British and Foreign State Papers 1837, p.773

- ↑ Congressional edition 1818, p.7 [47]

- ↑ Howard Jones (2009). Crucible of Power: A history of American foreign relations to 1913. Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Incorporated. pp. 108–112. ISBN 978-0-7425-6534-0. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ John Wallace Griffin (1996). Fifty years of southeastern archaeology: selected works of John W. Griffin. University Press of Florida. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8130-1420-3. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ De Quesada, p.138.

References

- National Register of Historic Places

- Adams, John Quincy, Memoirs of John Quincy Adams, comprising portions of his diary from 1795 to 1848. Volume 4. J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1875

- British and Foreign State Papers, Volume 5. Great Britain, Foreign and Commonwealth Office. HMSO. 1837

- Coker, William S., Florida from the beginning to 1992. Houston Texas, Pioneer Publications. 1991

- Congressional edition. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1818

- Congressional edition. Volume 934 United States Congress Miscellaneous documents of the 35th session of the United States Congress. United States Government Printing Office 1858

- Cusick, James G., The Other War of 1812: The Patriot War and the American Invasion of Spanish East Florida. Athens, University of Georgia Press. 2007

- Davis, T. Frederick, MacGregor's Invasion of Florida, 1817; Together with an account of his successors Hubbard and Aury on Amelia Island, East Florida. The Florida Historical Society quarterly. Volume 07 Issue 01. July 1928.

- De Quesada, Alejandro M., A History of Florida Forts. Charleston, South Carolina, The History Press p. 561 2006 ISBN 1-59629-104-4

- Ford, Worthington C., ed. Writings of John Quincy Adams. Volume 6. Macmillan. 1917

- Harper, Francis, editor, William Bartram, The Travels of William Bartram: Naturalist Edition. Athens, University of Georgia Press 1998 ISBN 0- 8203-2027-7

- Landers, Jane G., Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolutions. Harvard University Press, 2010

- McMurtrie, Douglas Crawford, Republic of the Floridas: Constitution and frame of government drafted by a committee appointed by the Assembly of representatives, and submitted at Fernandina, December 9, 1817. 5 pages Private printing 1942

- Miller, John, Narrative of a Voyage to the Spanish Main, in the Ship "Two Friends", The Occupation of Amelia Island, by M'gregor, &c. London, 1819

- Niles' Weekly Register, Volume 13. Franklin Press Baltimore, Maryland, September 1817–January 24, 1818

- O'Riordan, Cormac A., "The 1795 Rebellion in East Florida" (1995). UNF Theses and Dissertations. Paper 99. p. 13

- Owsley Jr., Frank Lawrence, and Smith, Gene A., Filibusters and Expansionists: Jeffersonian Manifest Destiny, 1800–1821. Tuscaloosa, Alabama 1997

- Perceval, J.J.; T77/5/5-47054 Additional Manuscripts, Egmont Papers, British Library London. Egmont to Grant, June 1, 1768, and Grant to Egmont, Dec. 23, 1767, in James Grant Papers

- State papers and Publick documents of the United States, from the accession of George Washington to the presidency: exhibiting a complete view of our foreign relations since that time ... United States Department of State, Volume 11, 3rd edition, Thomas B. Wait, 1819

- State papers and Publick documents of the United States, from the accession of George Washington to the presidency: exhibiting a complete view of our foreign relations since that time ... United States Department of State, Volume 12, 3rd edition, Thomas B. Wait, 1819

- Thomas, David Hurst, The Archaeology of Mission Santa Catalina de Guale. Volume 74, 1987

- Williams, John Lee, The Territory of Florida: or, Sketches of the Topography, Civil and Natural History, of the country, the climate, and the Indian tribes, from the first discovery to the present time, with a map, views, &c. New York, New York, A.T. Goodrich 1837

External links

- Florida's Office of Cultural and Historical Programs

- Nassau County listings

- City of Fernandina Beach

- 1811 Plat

- Map of the District

- Amelia Island Museum of History

- Fernandina Plaza Historic State Park

- Old Town Fernandina website

-

Media related to Original Town of Fernandina Historic Site at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Original Town of Fernandina Historic Site at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg)