Indonesian National Police

| Indonesian National Police Kepolisian Negara Republik Indonesia | |

|---|---|

| Abbreviation | POLRI |

|

Logo of Indonesian National Police | |

| Motto |

Rastra Sewakottama (Sanskrit) (Serving the People Above All) |

| Agency overview | |

| Legal personality | Governmental: Government agency |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| National agency (Operations jurisdiction) | ID |

| Legal jurisdiction | National |

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Kebayoran Baru, South Jakarta |

| Agency executive | Police General Tito Karnavian, Chief of Indonesian National Police |

| Website | |

|

www | |

The Indonesian National Police (Indonesian: Kepolisian Negara Republik Indonesia, POLRI) is the police force of Indonesia. It was formerly a part of the Indonesian National Armed Forces ("ABRI"). The police were formally separated from the military ("TNI") in April 1999, a process which was formally completed in July 2000.[1] The organization is now independent and is under the direct auspices of the President of Indonesia, while the Armed Forces is under the Ministry of Defense. Until this day, the Indonesian National Police is and still holds control of law enforcement and policing duties all over Indonesia nationally. The organization is widely known for its corruption, violence and incompetence.[2]

The Indonesian National Police is also taking part in international UN missions. The Indonesian Police Force has been providing security and protection to Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) for nearly one and half year while Indonesia’s Formed Police Units (FPUs) have been a very capable and integral part of UNAMID’s mandated-task of protecting people of Darfur.[3]

The strength of the Indonesian National Police ("POLRI") stood at approximately up-to 387,470 in 2011 and the number is increasing every year. It also includes up-to 12,000 water police ("Polair") personnel and an estimated 40,000 People’s Security ("KAMRA") trainees who serve as a police auxiliary and report for three weeks of basic training each year.

The headquarters, known as Markas Besar/Mabes in Indonesian, is located in Kebayoran Baru, South Jakarta near the national police museum.

History

When large parts of Indonesia was under Dutch colonial occupation until the 1940s, police duties were performed by either military establishments or colonial police known as the veldpolitie or the field police. Japanese occupation during WW II brought changes when the Japanese formed various armed organisations to support their war. This had led to the distribution of weapons to military trained youths, which were largely confiscated from the Dutch armoury.

After the Japanese occupation, the national police became an armed organisation. The Indonesian police was established in 1946, and its units fought in the Indonesian National Revolution against the invading Dutch forces. The police also participated in suppressing the 1948 communist revolt in Madiun. In 1966, the police was brought under the control of Armed Forces Chief, assuming the name Indonesian Police Force. Following the proclamation of independence, the police played a vital role when they actively supported the people’s movement to dismantle the Japanese army, and to strengthen the defence of the newly created Republic of Indonesia. The police were not combatants who were required to surrender their weapons to the Allied Forces. During the revolution of independence, the police gradually formed into what is now known as Kepolisian Negara Republik Indonesia (Polri) or the Indonesian National Police. In 2000, the police force officially regained its independence and now is separate from the military.

Duties and Tasks

The key tasks of the Indonesian National Police are to:

- maintain security and public order;

- enforce the law, and

- provide protection, and service to the community.

In carrying out these basic tasks, Police are to:

- perform control, guard, escort and patrol of the community and government activities as needed;

- supplying all activities to ensure the safety and smoothness of traffic on the road;

- to develop community awareness;

- as well as in the development of national law;

- implement order and ensure public safety;

- implement co-ordination, supervision, and technical guidance to the investigators, civil servants/authorities, and the forms of private security;

- implement the investigation against all criminal acts in accordance with the criminal procedure law and other legislation;

- implement identification such as police medical operations, psychology, and police forensic laboratory for the interests of the police task;

- Protect soul safety, property, society, and the environment from disturbances and/or disaster, including providing aid and relief to uphold human rights;

- Serving interests of citizens for a while before it is handled by the agency and/or authorities;

- Give services to the public in accordance with the interests of the police task environment;

- to implement other duties in accordance with the legislation, which in practice regulated by Government Regulation;

- Receive reports and/or complaints;

- crowd and public control;

- help resolve community disputes that may interfere with the public order;

- supervising the flow that can lead to the dismemberment or threaten the unity of the nation;

- publicising police regulations within the scope of police administrative authority;

- implementing special examination as part of the police identification;

- respond first and rapid action to a scene;

- Take the identity, fingerprints and photograph of a person for identification purposes;

- looking for information and evidence;

- organising National Crime Information Center;

- issuing license and / or certificate that is required to service the community;

- Give security assistance in the trial and execution of court decisions, the activities of other agencies, as well as community activities; and

- to Receive, secure, and keep founded lost items for a while until further identification

Organization

Polri is a centralised national bureaucracy.[4] As a national agency it has a large central headquarters in Jakarta (Markas Besar Polri or Mabes Polri). The regional police organisation parallels exactly the hierarchy of the Indonesian civic administration, with provincial police commands (Polisi Daerah or Polda) to cover provinces, district commands (Polisi Resor or Polres) for districts, sub-district commands (Polsek) and community police officers or Polmas to service individual villages.[5]

The Indonesian Police Force is not to be confused with the Municipal Police of Indonesia which is known in Indonesian as: "Satpol PP" (Civil Service Police Unit) which is the municipal police unit of Indonesia. Their uniform are slightly different with the Indonesian Police which is mainly all Khaki where in the other hand the Indonesian police force wear brownish grey and dark brown.

There are confusing terminological differences between some police commands. This derives from certain normative features of Indonesian governance. Indonesian political culture elevates the capital district (ibukota propinsi) of a province from other districts in the same province, though all have the same functional powers. Similarly, the capital province of the country (Jakarta), enjoys special normative status over other provinces – though in practice all have the same governmental responsibilities. The Indonesian police structure continues this by creating a special command for the province of Jakarta (Polda Metro Jaya), and special commands for capital city districts and cities (Polisi Kota Besar or Poltabes). Nevertheless, all of Indonesia’s police district commands (whether they are a Polres or Poltabes) and all the provincial commands (whether it is the flagship Polda Metro Jaya or one of the other Poldas) have the same powers and duties.[6]

As an additional complication, super large provinces like East, West and Central Java have intermediary co-ordinating commands (Polisi Wilayah or Polwil) designed to enhance co-ordination between provincial commands and districts (to illustrate, Polda Jawa Barat in West Java has no less than 29 district commands – a major challenge for command and control). However Polri has a stated commitment to dismantle these Polwil in the near future.[7]

Internal police culture is doctrinaire and hierarchical, and the organisation reflects this.[8] The design and duties of Poldas and Polres are determined by central edict.[9] Current standing orders determine that all provincial police are divided into three streams A1 (Polda Metro Jaya), B1 (demographically large provinces like East, Central and West Java) and B2 (smaller provinces like Yogyakarta, or West Kalimantan).[10] The structure of these Poldas is more or less the same, with each possessing: a directorate of detectives, narcotics, traffic police, intelligence, specialist operational units (such as Brimob – the paramilitary police strikeforce, water police, and other units), as well as support detachments like the provosts, Binamitra (social relations police), etc.[11] What truly differentiates Poldas is their resource base. Within Polri a tripartite matrix is applied to allocate personnel, money and equipment. This matrix is based upon a provinces’ square area, population size and reported crime rate. The same matrix is also applied to divide resources between Polres.[12] Turning to examine the Polres, the Polres is in essence the backbone of the Indonesian police – it bridges the purely operational units (Polsek), with the higher planning/strategic elements of the structure (the Polda). In the Indonesian police a Polres is termed the Komando Satuan Dasar (or Basic Unit of Command); this means that a Polres has substantial autonomy to implement its own activities and mount its own operations.[13] Regarding the structure of a Polres, a Polres is in effect a scaled down version of a Polda. Below is a cross-section of an average B1 level Polres (discreetly termed Polres A), in the province of Yogyakarta. This data derives from a recent PhD dissertation.[14] Polres A has fourteen separate detachments. Seven of these detachments can be described as support elements. These support elements consist of: an Operations Planning Section, a Community Policing Section, an Administration Section (providing human resource management, training co-ordination, etc.), a Telecommunications detachment (providing communications support), a Unit P3D (provosts - or the police who police the police), a Police Service Centre (for co-ordinating requests from the public), a Medical Support Group and the Polres Secretariat. Based on 2007 data, these support areas were staffed by 139 personnel. The largest support unit was the Polres Service Centre, with fifty one police. These seven support elements back up the work of Polres A’s seven other operational units (or Opsnal in Polri terminology) as well as the nineteen sub-district police precincts in this particular district.[15]

The Opsnal and sub-district commands execute Polri’s operational tasks. Polres A has one Traffic Police Unit, one Vital/Strategic Object Protection Unit, one Police Patrol Unit, one Narcotics Investigation Unit, one Detective Unit, a special tourist protection taskforce and a Police Intelligence Unit. These detachments have a combined strength of 487 personnel. The largest numbers are in the patrol unit (178) and the traffic unit (143). Added to the Opsnal personnel at the Polres headquarters are 1288 other police in nineteen sub-district Polseks. In 2007 this gave Polres a police-to-population ratio of around 1 police officer to 526 civilians.[16]

The allocation of the budget in Polres A is also illuminating for determining where police priorities are. In 2007, Polres A had a planned budget of Rp.62.358 billion ($US 5,668,909). Of this Rp.56 billion or 90% was spent on wages and office expenses. Thus, as with most organisations, personnel costs absorb the lion’s share of resources. In terms of the operational budget some Rp.4 billion or 6% was spent on daily activities and special operations. The remaining 4% was divided between community policing, intelligence gathering and criminal investigation.[17]

Corruption

In the eyes of the people, the National Police force is "corrupt, brutal, and inept".[2] Even becoming a police officer can be expensive, with applicants having to pay up to Rp90 million, according to Indonesia Police Watch head, Neta Saputra Pane.[18]

In 28 June 2010 and 21 April 2013,numerous Tempo magazines are bought in extremely numbered all over Jakarta by a group of people that wearing the police uniforms,Tempo said that the magazines are lifted some police officials secret bank account containing a million of united states dollar and exclusive property in South Jakarta.

In April 2009, angry that the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) had tapped his phone while investigating a corruption case, Indonesian Police chief detective Susno Duadji compared the KPK to a gecko (Indonesian: cicak) fighting a crocodile (Indonesian: buaya) meaning the police. Susno's comment, as it turned out, quickly backfired because the image of a cicak standing up to a buaya (similar to David and Goliath imagery) immediately had wide appeal in Indonesia. A noisy popular movement in support of the cicak quickly emerged. Students staged pro-cicak demonstrations, many newspapers ran cartoons with cicaks lining up against an ugly buaya, and numerous TV talk shows took up the cicak versus buaya topic with enthusiasm. As a result, references to cicaks fighting a buaya have become a well-known part of the political imagery of Indonesia.[19]

In June 2010, the Indonesian news magazine Tempo published a report on "fat bank accounts" held by senior police officers containing billions of rupiah. When the magazine went on sale in the evening groups of men said by witnesses to be police officers, went to newsstands with piles of cash to try to buy all the copies before they could be sold.[20][21]

When KPK investigators tried to search Polri headquarters in 2010 as part of an investigation into Djoko Susilo, then the head of Korlantas (police corps of traffic), they were detained, and only released following the intervention of the president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. Following a trial, Djoko was jailed for 18 years. Two years later, the KPK began investigating another senior police officer, Budi Gunawan, who was subsequently nominated for the post of National Police Chief. The KPK then named Budi a suspect and his nomination was withdrawn. However, he was later sworn in as deputy police chief. The police subsequently took revenge by charging three KPK commissioners with criminal offenses.[22][23]

In Bali, corrupt officers routinely extort bribes from tourists. In 2013 a YouTube appeared of a policemen demanding Rp200,000, which he then used to buy beer, which he drank with the tourist.[24]

In 2014,Budi Gunawan,the National police chief assistant candidate was being investigated by the national corruption commission for about two days after they found out that his income shows something strange. Media believe that he was protected by some big people and many people disagree when he was chosen as the national police chief assistant.Until now,many books and murals described Budi Gunawan and the police for their corruption.

Violence and human rights abuses

Amnesty International has accused Polri of "widespread" torture and other abuses of arrested individuals.[25] According to the organization, "Police in Indonesia shoot, beat and even kill people without fear of prosecution, leaving their victims with little hope of justice".[26]

In 2014 the Human Rights Watch reported that a physical virginity test is routinely performed on female applicants to the police force.[27] Human Rights Watch decried the practice as unscientific and degrading.[27]

An official admission of violence by police officers came in 2016 when Chief Gen. Badrodin Haiti admitted that officers of the Detachment 88 anti-terror unit were responsible for the death in custody of terrorist suspect Siyono, who died of heart failure after being kicked hard enough in the chest to fracture his ribs. The Indonesian National Commission on Human Rights stated in March 2016 that at least 121 terror suspects had died in custody since 2007[28]

Special Police Units

Mobile Brigade Corps

The Mobile Brigade Police force of Indonesia (BRIMOB POLRI) or (BRIMOB) is the elite/special forces of the Indonesian National Police. Brimob is the paramilitary force of Indonesia and takes the duties for handling high-level threat of public secure also special police operations. This unit also becomes the back-up force for the riot control purposes. The personnel of this unit are identifiable with their dark blue berets.

The Mobile Brigade is also known as the special ‘anti-riot’ branch of the Indonesian National Police which deals with special operations. A paramilitary organization, its training and equipment is almost identical to the Indonesian Army’s ("TNI"), and it conventionally operates under joint military command in areas such as Papua and, until 2005, Aceh.[29]

Gegana

GEGANA is an internal unit of the Brimob special Police corps who have special abilities in the field of anti-terrorism, bomb disposal, intelligence, anti-anarchist, and handling of Chemical, Biological, and Radio Active threats. Its main specialty are bomb disposal and explosives treatment during in urban settings.

Detachment 88

The Detachment 88 or Densus 88 is an Indonesian Police Special Forces squad specialty in the field of counter-terrorism. Their identities are usually kept secret, and usually operate with unmarked Toyota Kijang vehicles.

Police Units

There are several units within the National Police of Indonesia which is known as Kesatuan which are:

Sabhara

SABHARA (Samapta Bhayangkara) is the main public unit of the National Police of Indonesia that directly supervises the public order and public security. It is the most common police unit in the country which actively conducts patroling and community service. This unit becomes the first dispatch for standard law enforcement, policing activities and public matters affairs.

The "Sabhara" unit is also the first dispatched force for riot control before seeking back-up from the Brimob unit if the riot gets more violent. The personnel of this police unit are identifiable with their dark brown berets and usually are stationed in mostly police offices or police stations across Indonesia.

Traffic Police Corps

Website: http://lantas.polri.go.id

The Traffic Police of Indonesia (Indonesian: Polantas/Korlantas POLRI) is the traffic police law enforcement unit of the Indonesian National Police Force which have specialty in duty for directing, controlling, patrolling, and to take action in traffic situations in the streets, roads, and highway of the country. This unit also serves for the issuing of the Driving licence in Indonesia. They are very common in the streets and always take part in a traffic accident. In 2012, about 30 police officers were sent to the Netherlands national police to learn about the Traffic Accident Analysis or simply "TAA".

Maritime Police Force

Website: http://polair.polri.go.id/

The Indonesian Maritime Police Force (Indonesian: Polisi Perairan/POLAIR) is the water police force of Indonesia which guards and secures the sea and coast of Indonesia. This unit also takes action in illegal fishing activities and conducts law enforcement of fishermen and their boat's registrations in the naval territory of the republic.Their headquarters and training facility are in Kepulauan Seribu

Police Aviation

The Police Aviation of Indonesia (Indonesian: Polisi Udara) is a police unit in charge of conducting policing and law enforcement functions throughout and from the air territory of the Republic of Indonesia. It is in order to provide support (backup) for police operations to be observed from the air and to enable assistance for police duties such as ground support, search and rescue, and air patrol observations. The helicopter identifiable of this police unit is usually colored white and blue in Indonesia.

Tourism Police

The Tourism Police (Indonesian: Polisi Wisata) is a police unit for tourist services. They are sometimes identifiable with their unique Indonesian Police uniform with dark brown cowboy hats and short pants and usually conducts patrolling along the beaches of Indonesia especially in Bali.

Vital Object Protection

PAM OBVIT (Indonesian: unit Pengamanan Objek Vital) is an Indonesian police unit for vital protection and usually secures international embassies and consulate in Indonesia and VIP escort but sometimes, they protecting beaches, temples and churches in some case. Their vehicles are colored orange, same as the airport police car and usually parked outside of the embassies in Indonesia. The personnel of this unit wear additional Neckties and usually wear peaked cap for their uniform.

Sea Port Police

KPPP or KP3 (Indonesian: Kesatuan Pelaksanaan Pengamanan Pelabuhan) is an element of the Indonesian National Police which has the main task to assist the Port Administrator in organizing security at the Port area along the common discipline in the context of utilization and exploitation of the port.

Bareskrim

Bareskrim or RESKRIM (Indonesian: Badan Reserse Kriminal), lit; Criminal Investigation Agency, is an internal police unit of the Indonesian national police, its main duty is to investigate criminal activity and crime identification

Security Intelligence Agency

BAINTELKAM POLRI (Indonesian: Badan Intelijen dan Keamanan Polisi Republik Indonesia) is one of the main tasks of police executing agency in the field of intelligence.

PUSLABFOR

Puslabfor or simply LABFOR is the abbreviation of (Indonesian: Pusat Laboratorium dan Forensik) which is a unit for the agency and investigation in the field of forensics and laboratory purposes.

NCB Interpol

The International Criminal Police Organization also called ICPO-Interpol is a joint organization for the handling of cross-country crime. In 1954, Indonesia became a member of ICPO-Interpol and established the National Central Bureau (NCB) as a police agency to maintain cooperation between countries within the scope of ICPO-Interpol. In addition to the handling of transnational crimes, this unit maintains cooperation with foreign Police elements in the matter of criminal activity involving national and international links. The NCB Interpol are very important for the agency because many corrupt government officials are like to escape to another country especially Singapore. The NCB is headquartered at Jl. Trunojoyo no.3 Kebayoran baru near the national police headquarters and the ASEAN secretariat building

Polisi Satwa

Subdit-Satwa (Indonesian: Polisi Satwa) is an Indonesian Police unit in the specialization of wild-life and animal affairs. This unit provides K-9 dogs for police activity and investigation. This unit also deploys Mounted police for several occasions like riot control.

Directorate of Narcotics and Drugs

This police unit is known as (Indonesian: Direktorat Reserse Narkoba) is a police unit responsible for the handling and prosecution of illegal drugs and narcotics.

Div PROPAM

(Indonesian: Divisi Profesi dan Pengamanan Polisi) or is known as DIV PROPAM or PROVOS is the internal affairs of the Indonesian National Police. This police unit supervises and maintains discipline in the internal scope of the national police. Personnel of this unit are identifiable with their blue berets and wear dark blue brassard printed 'PROV'. Internal investigation of police personnel and officers are conducted by these officers and they also have strong authority within the Indonesian police scope. They act as "Provosts" in the Indonesian National Police just like Military police in the military.

Police Operational Centers

In the country, the police services in the community are made into several posts or office which represent a region:

- POLPOS or Pos Polisi is the police post. It is usually stationed near traffic intersections for traffic police posts and are also available in public places and public transportation stations.

- POLSUBSEK or Polisi Sub-Sektor is the police station for a specific smaller region or village. The level is bellow of a Polsek and level as to above a Polpos.

- POLSEK or Polisi Sektor is the police office for a specific sub-district or kecamatan. For example: POLSEK Kuta.

- POLRES or Polisi Resor is the police base for a city. For some big cities, sometimes it is known as POLRESTABES or POLRESTA which is the abbreviation of Polisi Resor Kota/Kota Besar. For example: POLRESTA Denpasar.

- POLDA or Polisi Daerah is the police headquarters for a province. For example: POLDA Bali.

Firearms

The standard issue sidearm to all Indonesian National Police officers is the Taurus Model 82 revolver in. 38 Special. While police personnel attached to special units such as Detachment 88, Gegana and BRIMOB are issued with the Glock 17 semi-automatic pistol.

Heavy arms are always available to Indonesian police personnel, such as the Heckler & Koch MP5 sub-machine gun, Remington 870 shotgun, Steyr AUG assault rifle, M4 carbine, M1 Carbine. and other weapons. The standard rifle for the Indonesian National Police are the Pindad SS1 and the M16 rifle. Units are also issued the "Sabhara"/Police V1-V2 Pindad SS1 special law enforcement assault rifle.

Police Fleets

The police vehicles that are usually operated by the Indonesian Police ("Polri") for patrol and law enforcement activities are mainly Ford Focus sedans, Mitsubishi Lancers, Hyundai Elantras (for some police regions), Mitsubishi Stradas, Isuzu D-Maxs, and Ford Rangers. Such vehicles are usually operated by the "Sabhara" police unit and other units which the vehicles are mainly colored dark-grey. In some areas, usually in rural places, the vehicles are not up-to date compared to the ones in the major urban areas in the country, so some police vehicles still use older versions such as the Toyota Kijang and Mitsubishi Freecas.

Special Investigation units usually operate in black Toyota Avanzas and some are unmarked vehicles. Police laboratory and forensics ("Puslabfor") units are issued dark-grey police Suzuki APV vehicles.

The Traffic Police Corps ("Korlantas") usually uses vehicles such as the Mazda 6, Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution, Toyota Vios, Ford Focus sedans, Hyundai Elantra and Ford Rangers colored white and blue. Some vehicles for traffic patrol are also used such as the Toyota Rush and Daihatsu Terios. Sedan types are usually used for highway and road patrolling and escort. Double-Cab types are usually used for Traffic incidents and traffic management law enforcement activities.

Police vehicles colored orange usually Ford Focus and Mitsubishi Lancer sedans and white-orange Chevrolet Captivas are operated by the Vital Object Protection unit ("Pam Obvit") and usually parked outside and operated for international embassies, airports, and other special specified locations. It is also used by the Tourist police for patrol.

For the special police, counter-terrorism and anti-riot units such as the Mobile Brigade or "Brimob", Detachment 88 and "Gegana" units usually use special costumed vehicles for special operations such as the Pindad Komodo, Barracuda APC, and modified armored Mitsubishi Stradas, 2002 Nissan Terrano Spirits' and other special double-cabin and SUV vehicle types. Vehicles are colored dark-grey with the bumper colored orange identifying vehicles of the special police units. Some special operational "Gegana" and "Densus 88" vehicles are colored black also with orange bumpers.

Other customized vehicles used for mobilization of police personnel are usually modified Isuzu Elfs and Toyota Dynas with horizontal side sitting facilities inside of the trunk covered by dark colored canvas for canopy. Costumed patrol pick-ups with mounted sitting facilities on the trunk covered with canopy are also operated by the police to carry police personnel during patrol, the pick-ups are usually Isuzu Panther pick-ups and usually operate in rural areas.

For high-ranking officers (usually generals), issued cars are usually grey (some black) full to compact sedans and Mid to Full-sized SUVs. Such cars are mainly chauffeured Toyota Camrys, Hyundai Sonatas, Toyota Land Cruisers, and Toyota Prados. Some use black Toyota Innovas.

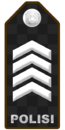

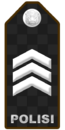

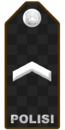

Ranks

In the early years, the Indonesian Police used European police style ranks like "inspector" and "commissioner". When the police were amalgamated with the military structure during the 1960s, the ranks changed to a military style such as "Captain", "Major" and "Colonel". In the year 2000, when the Indonesian Police conducted the transition to a fully independent force out of the armed forces in 2000, they used British style police ranks like "Inspector" and "Superintendent". Now, The Indonesian Police have returned to Dutch style ranks like "Brigadier" and "Agents" just like in the early years with some Indonesianized elements within the ranking system.

| Worn on: | High Ranking officers | Middle Ranking officers | First Ranking officers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceremonial Uniform (PDU) |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Service Uniform (PDH) |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Field Uniform (PDL) on collar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rank: | Police General | Commissioner General | Inspector General | Brigadier General | Police Chief commissioner | Police superintendent | Police Commissioner | Police Chief Inspector | First Inspector | Second Inspector |

| Worn on: | Asst. Inspector | Brigadiers (NCO/Constable) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceremonial Uniform (PDU) |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Service Uniform (PDH) |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Field Uniform (PDL) on collar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rank: | Police Sub-inspector | Second sub-inspector |

Chief Brigadier |

Brigadier | First Brigadier |

Second Brigadier |

- The Ranks below is only used in the Mobile Brigade ("Brimob") and Water police units:

| Worn on: | Enlisted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceremonial Uniform (PDU) |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Service Uniform (PDH) |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| Field Uniform (PDL) on collar |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rank: | Brigadier Adjutant |

First Brigadier Adjutant |

Second Brigadier Adjutant |

Chief Agent |

First Agent |

Second Agent |

Uniform

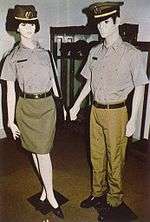

The National Police Force of Indonesia had changes for uniform colours about 3 times, the periods are:

- Since first formed until mid 70s, the uniform colour was khaki like the current Indian Police uniform.

- Since the late 70s until mid 90s, the uniform colour was light brown and brown.

- Since mid 90s until now the colour are brownish grey and dark brown.

In the Indonesian Armed Forces and Police, there are three types of uniform worn by service personnel. there are Ceremonial uniform, service uniform, and field uniform. The one on the picture (right) is an example of service uniform of the police force. Field uniform example is at the "Sabhara" unit above.

List of Chiefs of Police (Kapolri)

- General R Said Soekanto Tjokrodiatmodjo (29 Sep 1945 – 14 December 1959)

- General Soekarno Djojonegoro (15 December 1959 – 29 December 1963)

- General Soetjipto Danoekoesoemo (30 December 1963 – 8 May 1965)

- General Soetjipto Joedodihardjo (9 May 1965 – 8 May 1968)

- General Hoegeng Iman Santoso (9 May 1968 – 2 October 1971)

- General Moch. Hasan (3 October 1971 – 1974)

- General Widodo Budidharmo (1974 – 25 September 1978)

- General Awaluddin Djamin (26 September 1978 – 1982)

- General Anton Soedjarwo (1982 – 1986)

- General Mochammad Sanoesi (1986 – 19 February 1991)

- General Kunarto (20 February 1991 – April 1993)

- General Banurusman Astrosemitro (April 1993 – March 1996)

- General Dibyo Widodo (March 1996 – 28 June 1998)

- General Roesmanhadi (29 June 1998 – 3 January 2000)

- General Roesdihardjo (4 January 2000 – 22 September 2000)

- General Suroyo Bimantoro (23 September 2000 – 28 November 2001)

- General Da'i Bachtiar (29 November 2001 – 7 July 2005)

- General Sutanto (8 July 2005 – 30 September 2008)

- General Bambang Hendarso Danuri (30 September 2008 – October 2010)

- General Timur Pradopo (October 2010 – 25 October 2013)

- General Sutarman (25 October 2013 – 16 January 2015)[30][31]

- General Badrodin Haiti (17 April 2015 – 13 July 2016)

- General Tito Karnavian (13 July 2016 — present)

Police Vehicles

-

Indonesian police patrol car

-

Mazda 6 Indonesian Traffic Police cars

-

Customized Ford Ranger Mobile Brigade Special Police Operational vehicle

-

Pindad Komodo Indonesian Mobile Brigade special police tactical vehicle

-

Police Mobile Brigade riot vehicle

-

Yamaha Indonesian Traffic police motorcycle

-

Indonesian traffic police car

-

Rear view of the Indonesian traffic police patrol car

-

Mitsubishi Lancer Indonesian Vital Object Protection ("Pam Obvit") unit patrol car

-

.jpg)

Barracuda APC Mobile Brigade riot control vehicle

-

Mitsubishi Lancer Indonesian police patrol car

-

.jpg)

Daihatsu Gran Max Indonesian Tourist Police Service Van

-

An Indonesian Police patrol vehicle circa 1976

-

An Indonesian K9 Police Unit Vehicle

-

Police Off-Road Motorcycle (Dirt Bike) units

See also

- Indonesian Military (TNI)

- Indonesian Mobile Brigade Special Police Corps (Brimob)

- Detachment 88 (Densus 88) AT

- "GEGANA" Indonesian Special Police Bomb Disposal Unit

- Civil Service Police Unit: Indonesian Municipal police unit (Satpol PP)

- Indonesian Military Police Corps

References

- ↑ "Indonesian police split from military", Reuters, CNN, 1 April 2009, retrieved 18 September 2009

- 1 2 Davies, Sharyn Graham; Meliala, Adrianus; Buttle, John, Indonesia’s secret police weapon (Jan-Mar 2013 ed.), Inside Indonesia, retrieved 8 December 2015

- ↑ "Sudan Focus: United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) introduces Community Policing in Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps in Khartoum", UN, United Nations, October 2008, retrieved 6 March 2016

- ↑ Republik Indonesia: Undang-Undang No.2/2002 tentang Kepolisian Nasional, Pasal 8. [Indonesian National Police Law].

- ↑ David Jansen, ‘Networked Security in Indonesia: The Case of the Police in Yogyakarta.’ Doctoral Dissertation, Australian National University (April 2010), p.70-71.

- ↑ Keputusan Kepala Kepolisian Negara Republik Indonesia No.Pol. : KEP 7/I/2005 tentang Perubahan Atas Keputusan Kapolri No.Pol KEP /54/X/2002 Tanggal 17 Oktober 2002 tentang Organisasi dan Tata Kerja Satuan-Satuan Organisasi pada Tingkat Kepolisian Negara Republik Indonesia Daerah (Polda) Lampiran A Polda Umum, B Polda Metro Jaya dan C Polres.

- ↑ "West Java Polda - Sekilas Mapolda Jabar". Lodaya.web.id. 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011. For commitment to deconstruct Polwil see: 2010, Polwiltabes Jadi Polrestabes’, Tribun Makassar, 23 December 2009

- ↑ Jansen, ‘Networked Security in Indonesia’, 74.

- ↑ See footnote four for central headquarters policy on structure and organizational function.

- ↑ See footnote four.

- ↑ Most Polda websites have a basic overview of their functional units A good one to start is Polda Jawa Barat.

- ↑ See footnote four. See also: Mulyana, Laporan Hasil Penelitian: Telaah Tiplogi Polres Berdasarkan Karakteristik dan Perkembangan Wilayah (Universitas Padjadjaran, Sept.2007), p.13.

- ↑ Jansen, ‘Networked Security in Indonesia’, 71.

- ↑ Jansen, ‘Networked Security in Indonesia’ 71-73.

- ↑ The Polsek is a purely operational unit (or in Polri terms Kesatuan Pelayanan Terdepan – the Primary Forward Service Unit). The Polsek covers the territory of a single, civilian sub-district (or kecamatan). Depending on the classification of its area, a Polsek usually has between 30-70 personnel, consisting of an intelligence unit, a detective unit, a patrol police unit, two Polmas/Babinkamtibmas (social order guidance police) for every village in the sub-district, and, if the sub-district is large enough, a traffic police unit.

- ↑ District population figures derived from ‘Tabel 3.1.6 Jumlah Rumah Tangga dan Penduduk menurut Jenis Kelamin dan Kabupaten/Kota di Provinsi D.I.Yogyakarta (2004-2006).’ In: Badan Pusat Statistik: Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta Dalam Angka 2006/2007 (Katalog BPS: 1403.34), p.72.

- ↑ Jansen, ‘Networked Security in Indonesia’, 71-72.

- ↑ Allard, Tom (10 May 2010), Indonesia pays a high price for its corrupt heart, Sydney Morning Herald, retrieved 8 December 2015

- ↑ Antagonism between the KPK and the police, with memories of the cicak versus buaya clash, remained deeply embedded in the relationship between the KPK and the police after the clash. See, for example, references to the clash in 2012 in Ina Parlina, 'Doubts over KPK inquiry into police bank accounts', The Jakarta Post, 18 May 2012.

- ↑ Fat Bank Accounts of POLRI Chief Candidates, Tempo, 26 July 2013, retrieved 8 December 2015

- ↑ Deutsch, Anthony (29 June 2010), The disappearing magazine and Indonesian media freedom, Financial Times, retrieved 8 December 2015

- ↑ Butt, Simon; Lindsey, Tim (11 April 2015), Joko Widodo's support wanes as Indonesia's anti-corruption agency KPK rendered toothless, The Age, retrieved 8 December 2015

- ↑ Budi Gunawan sworn in as deputy police chief, The Jakarta Post, 22 April 2015, retrieved 8 December 2015

- ↑ Taking bribes from tourists Indonesian Style, ETurboNews, 28 April 2013, retrieved 8 December 2015

- ↑ Cop Killers, The Economist, 4 November 2010, retrieved 8 December 2015

- ↑ Indonesia must end impunity for police violence, Amnesty International, 25 April 2012, retrieved 8 December 2015

- 1 2 Human Rights Watch (18 November 2014). "Indonesia: 'Virginity Tests' for Female Police". Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- ↑ Eko Prasetyo (22 April 2016), Police Negligence Admission only Tip of the Iceberg: Amnesty International, The Jakarta Globe, retrieved 22 April 2016

- ↑ "Background on Kopassus and Brimob", etan., etan.org, 2008, retrieved 6 March 2016

- ↑ "Komisi III DPR Terima Sutarman Jadi Kapolri". 17 October 2013.

- ↑ "Komjen Pol Sutarman Resmi Dilantik Jadi Kapolri". 25 October 2013.

-

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

Further reading

- Amnesty International. (2009) "Indonesia: Unfinished Business: Police Accountability in Indonesia" (24 June 2009)

- International Crisis Group. (2001) Indonesia : National Police reform. Jakarta / Brussels : International Crisis Group. ICG Asia report; no.13

- David Jansen. (2008) "Relations among security and law enforcement institutions in Indonesia", Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol.30, No.3, 429-54

- "Networked Security in Indonesia: The Case of the Police in Yogyakarta." Doctoral Dissertation, Australian National University (April 2010).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indonesian National Police. |