Paul Barras

| Viscount of Barras Paul François Jean Nicolas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Director of the French Directory | |

|

In office 5 October 1795 – 10 November 1799 | |

| Preceded by |

Office created (Preceded by the President of the Committee of Public Safety De Cambacérès) |

| Succeeded by |

Office abolished (Succeeded by the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte) |

| 71th President of the National Convention | |

|

In office 4 February 1795 – 18 February 1795 | |

| Preceded by | Stanislas Joseph François Xavier Rovère |

| Succeeded by | François Louis Bourdon |

| Member of the National Convention | |

| Constituency | Var |

|

In office 20 September 1792 – 10 November 1799 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

30 June 1755 Fox-Amphoux, France |

| Died |

29 January 1829 (aged 73) Chaillot (present-day Paris), France |

| Political party |

The Mountain (1792–1794) Thermidorian (1794–1799) |

| Spouse(s) | Unknown wife (left) |

| Domestic partner |

Sophie Arnould, Thérésa Tallien, Joséphine de Beauharnais |

| Profession | Military officer |

| Religion | Catholic Church (baptized) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1771–1783 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Régiment Royal Roussillon |

| Battles/wars | |

Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras (30 June 1755 – 29 January 1829), commonly known as Paul Barras, was a French politician of the French Revolution, and the main executive leader of the Directory regime of 1795–1799.

Early life

Descended from a noble family of Provence, he was born at Fox-Amphoux, in today's Var département.[1] At the age of sixteen, he entered the regiment of Languedoc as a "gentleman cadet". In 1776, he embarked for French India.[1][2]

Shipwrecked on his voyage, he still managed to reach Pondicherry in time to contribute to the defence of that city during the Second Anglo-Mysore War.[1] Besieged by British forces, the city surrendered on 18 October 1778; after the French garrison was released, Barras returned to France.[2][Note 1] He took part in a second expedition to the region in 1782/83, serving in the fleet of the renowned Admiral Pierre André de Suffren.[1] Afterwards, he spent several years back home in France at leisure in relative obscurity.[1][2]

National Convention

At the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, he advocated the democratic cause, and became one of the administrators of the Var. In June 1792 he took his seat in the high national court at Orléans. Later in that year, on the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars, Barras became commissioner to the French Army, which was facing the forces of Sardinia in the Italian Peninsula, and entered the National Convention as a deputy for the Var.

In January 1793, he voted with the majority for the execution of King Louis XVI. However, he was mostly absent from Paris on missions to the regions of the south-east of France. During this period, he made the acquaintance of Napoleon Bonaparte at the siege of Toulon (his later clash with Napoleon made him downplay the latter's abilities as a soldier: he noted in his Memoirs that the siege had been carried out by 30,000 men against a minor royalist defending force, whereas the real number was 12,000; he also sought to minimize the share taken by Bonaparte in the capture of the city).[3] When Barras became Director, he gave Napoleon position of general in the battalion of Italians.[4]

Thermidor and the Directory

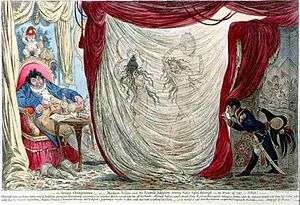

In 1794, Barras sided with the men who sought to overthrow Maximilien Robespierre's faction. The Thermidorian Reaction of 27 July 1794 made him rise to prominence. In the next year, when the Convention felt threatened by the malcontent National Guards of Paris, it appointed Barras to command the troops engaged in its defence. His nomination of Bonaparte led to the adoption of violent measures, ensuring the dispersion of royalists and other malcontents in the streets near the Tuileries Palace, remembered as the 13 Vendémiaire (5 October 1795). Subsequently, Barras became one of the five Directors who controlled the executive of the French Republic.

Owing to his intimate relations with Joséphine de Beauharnais, Barras helped to facilitate a marriage between her and Bonaparte. Some of his contemporaries alleged that this was the reason behind Barras' nomination of Bonaparte to the command of the army of Italy early in the year 1796. Bonaparte's success gave to the Directory an unprecedented stability, and when, in the summer of 1797, the royalist and surviving Girondist opposition again met the government with resistance, Bonaparte sent General Augereau, a Jacobin, to repress their movement in the Coup of 18 Fructidor (4 September 1797).

Downfall and later life

Barras' alleged immorality in public and private life is often cited as a major contribution to the fall of the Directory, and the creation of the Consulate. In any case, Bonaparte met little resistance during his 18 Brumaire coup of November 1799. At the same time, Barras is seen as a supporter of the change, one left aside by the First Consul when the latter reshaped the government of France.

Since he had amassed a large fortune, Barras spent his later years in luxury. Napoleon had him confined to the Château de Grosbois (Barras' property), then exiled to Brussels and Rome, and ultimately, in 1810, interned in Montpellier; set free after the fall of the Empire, he died in Chaillot (nowadays in Paris), and was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Although a partisan of the Second Restoration, Barras was kept in check during the reigns of Louis XVIII and Charles X (and his Memoirs were censored after his death).

Notes

- ↑ He left on a cartel named Sartine. This was not the Sartine that the British Royal Navy had captured at Pondicherry and taken into service. On 1 May 1780 a British warship mistakenly fired on the cartel, killing her captain and two others. Barras was unhurt.

References

- Bibliography

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barras, Paul François Nicolas, Comte de". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Barras, Paul François Nicolas, Comte de". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Canteleu, Jean-Barthélemy Le Couteulx de (2008). "Bonaparte in Barras's Salon". In Blaufarb, Rafe. Napoleon: Symbol for an Age, A Brief History with Documents. New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 0312431104.

- Richardson, Hubert N. B. (1920). A Dictionary of Napoleon and His Times. London: Cassell & Co.

Further reading

- Barras, chef d'Etat oublié by Pierre Temin (1992). ISBN 2884150137. (French)

._D%C3%A9claration_des_Droits_et_des_Devoirs_de_l'Homme_et_du_Citoyen.jpg)