Pennate muscle

| Rectus femoris | |

|---|---|

|

Muscles of the iliac and anterior femoral regions. (Rectus femoris highlighted in red.) | |

| Details | |

| Origin | anterior inferior iliac spine and the exterior surface of the bony ridge which forms the iliac portion of the acetabulum |

| Insertion | inserts into the patellar tendon as one of the four quadriceps muscles |

| Artery | lateral femoral circumflex artery |

| Nerve | femoral nerve |

| Actions | knee extension; hip flexion |

| Antagonist | Hamstring |

A pennate or pinnate muscle (also called a penniform muscle) is a muscle with fascicles that attach obliquely (in a slanting position) to its tendon. These types of muscles generally allow higher force production but smaller range of motion[1] [2] When a muscle contracts and shortens, the pennation angle increases[3]

Etymology

From the Latin pinnatus “feathered, winged,” from pinna “feather, wing.”

Types of pennate muscle

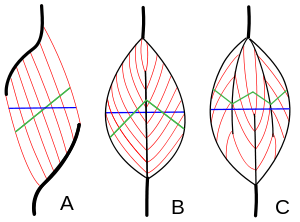

In muscle tissue, 10-100 endomysium-sheathed muscle fibers are organized into perimysium-wrapped bundles known as fascicles. Each muscle is composed of a number of fascicles grouped together by a sleeve of connective tissue, known as an epimysium. In a pennate muscle, aponeuroses run along each side of the muscle and attach to the tendon. The fascicles attach to the aponeuroses and form an angle (the pennation angle) to the load axis of the muscle. If all the fascicles are on the same side of the tendon, the pennate muscle is called unipennate (Fig. 1A). Examples of this include certain muscles in the hand. If there are fascicles on both sides of the central tendon, the pennate muscle is called bipennate (Fig. 1B). The rectus femoris, a large muscle in the quadriceps, is typical. If the central tendon branches within a pennate muscle, the muscle is called multipennate (Fig. 1C), as seen in the deltoid muscle in the shoulder.

Consequences of pennate muscle architecture

Physiological cross sectional area (PCSA)

One advantage of pennate muscles is that more muscle fibers can be packed in parallel, thus allowing the muscle to produce more force, although the fiber angle to the direction of action means that the maximum force in that direction is somewhat less than the maximum force in the fiber direction.[4][5] The muscle cross sectional area (blue line in figure 1, also known as anatomical cross section area, or ACSA) does not accurately represent the number of muscle fibers in the muscle. A better estimate is provided by the total area of the crossections perpendicular to the muscle fibers (green lines in figure 1). This measure is known as the physiological cross sectional area (PCSA), and is commonly calculated and defined by the following formula (an alternative definition is provided in the main article):[6][7][8]

where ρ is the density of the muscle:

PCSA increases with pennation angle, and with muscle length. In a pennate muscle, PCSA is always larger than ACSA. In a non-pennate muscle, it coincides with ACSA.

Relationship between PCSA and muscle force

The total force exerted by the fibers along their oblique direction is proportional to PCSA. If the specific tension of the muscle fibers is known (force exerted by the fibers per unit of PCSA), it can be computed as follows:[9]

However, only a component of that force can be used to pull the tendon in the desired direction. This component, which is the true muscle force (also called tendon force[8]), is exerted along the direction of action of the muscle:[8]

The other component, orthogonal to the direction of action of the muscle (Orthogonal force = Total force × sinΦ) is not exerted on the tendon, but simply squeezes the muscle, by pulling its aponeuroses toward each other.

Notice that, although it is practically convenient to compute PCSA based on volume or mass and fiber length, PCSA (and therefore the total fiber force, which is proportional to PCSA) is not proportional to muscle mass or fiber length alone. Namely, the maximum (tetanic) force of a muscle fiber simply depends on its thickness (cross-section area) and type. By no means it depends on its mass or length alone. For instance, when muscle mass increases due to physical development during childhood, this may be only due to an increase in length of the muscle fibers, with no change in fiber thickness (PCSA) or fiber type. In this case, an increase in mass does not produce an increase in force.

Lower velocity of shortening

In a pennate muscle, as a consequence of their arrangement, fibers are shorter than they would be if they ran from one end of the muscle to the other. This implies that each fiber is composed of a smaller number N of sarcomeres in series. Moreover, the larger is the pennation angle, the shorter are the fibers.

The speed at which a muscle fiber can shorten is partly determined by the length of the muscle fiber (i.e., by N). Thus, a muscle with a large pennation angle will contract more slowly than a similar muscle with a smaller pennation angle.

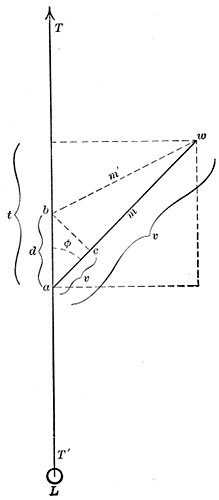

Architectural gear ratio

Architectural gear ratio, also called anatomical gear ratio, (AGR) is a feature of pennate muscle defined by the ratio between the longitudinal strain of the muscle and muscle fiber strain. It is sometimes also defined as the ratio between muscle-shortening velocity and fiber-shortening velocity:[10]

AGR = εx/εf

where εx = longitudinal strain (or muscle-shortening velocity) and εf is fiber strain (or fiber-shortening velocity).[10]

It was originally thought that the distance between aponeuroses did not change during the contraction of a pennate muscle,[5] thus requiring the fibers to rotate as they shorten. However, recent work has shown this is false, and that the degree of fiber angle change varies under different loading conditions. This dynamic gearing automatically shifts in order to produce either maximal velocity under low loads or maximal force under high loads.[10][11]

References

- ↑ Frederick H. Martini, Fundamentals Of Anatomy And Physiology.

- ↑ Jacob Wilson, Abcbodybuilding, The Journal of HYPERplasia Research

- ↑ Maganaris CN, Baltzopoulos V, Sargeant AJ. In vivo measurements of the triceps surae complex architecture in man: implications for muscle function. J Physiol. 1998, 512:603-614.

- ↑ C. Gans (1982) Fiber architecture and muscle function. Exercise & Sports Science Reviews. 10:160-207.

- 1 2 E. Otten (1998). Concepts and models of functional architecture in skeletal muscles. Exercise & Sports Science Reviews. 16:89-137.

- ↑ R. McN. Alexander, A. Vernon (1975). The dimension of knee and ankle muscles and the forces they exert, Journal of Human Movement Studies, 1:115–123.

- ↑ Narici M.V., Landoni L., Minetti A.E. (1992). Assessment of human knee extensor muscles stress from in vivo physiological cross-sectional area and strength measurements. European Journal of Applied Physiology & Occupational Physiology. 65(5):438-444.

- 1 2 3 Maganaris C.N., Baltzopoulos V. (2000). In vivo mechanics of maximum isometric muscle contraction in man: Implications for modelling-based estimates of muscle specific tension. In Herzog W. (Ed). Skeletal muscle mechanics: from mechanisms to function. Wiley & Sons Ltd, p.267-288.

- ↑ R.D. Sacks, R.R. Roy (1982). Architecture of The Hind Limb Muscles of Cats: Functional Significance. Journal of Morphology, 185-195.

- 1 2 3 Azizi, E. and Brainerd, E.L. (2007)."Architectural Gear Ratio and Muscle Fiber Strain Homogeneity in Segmented Musculature." Journal of Experimental Zoology. 307A:145-155.

- ↑ http://www.pnas.org/content/105/5/1745.abstract