Pleione (star)

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

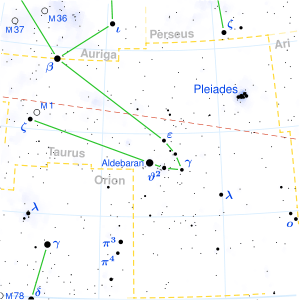

| Constellation | Taurus |

| Right ascension | 03h 49m 11.2161s[1] |

| Declination | 24° 08′ 12.163″ [1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 5.048 [1] |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | B8IVpe [2] |

| U−B color index | -0.28 |

| B−V color index | -0.08 [3] |

| Variable type | Gamma Cassiopeiae |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | 4.4 [1] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 18.71 [1] mas/yr Dec.: -46.74 [1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 8.32 ± 0.13[4] mas |

| Distance | 392 ± 6 ly (120 ± 2 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | -0.33 |

| Details | |

| Mass | 3.4 [5] M☉ |

| Radius | 3.2 [5] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 190 [5] L☉ |

| Temperature | 12,000 [5] K |

| Metallicity | ? |

| Rotation | 329 km/s [6] |

| Age | 1.15×108 years |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

Coordinates: ![]() 03h 49m 11.2161s, +24° 08′ 12.163″

03h 49m 11.2161s, +24° 08′ 12.163″

Pleione, designated 28 Tauri (abbreviated 28 Tau) and BU Tauri, is a binary star and the seventh-brightest star in the Pleiades star cluster (M45) and is located approximately 390 light years from the Sun in the constellation of Taurus. Since the star is located close to Atlas, it's difficult for stargazers to distinguish with the naked eye, even though it's a hot type B star 190 times more luminous than the Sun. Pleione rotates even faster than Achernar on its axis, close to its breakup velocity.

The brighter star of the binary pair, component A, is a classical Be star with certain distinguishing traits: periodic phase changes and a complex circumstellar environment composed of two gaseous disks at different angles to each other. Although some research on the system has been performed, stellar characteristics of the orbiting B component are not well known.

Nomenclature

28 Tauri is the star's Flamsteed designation and BU Tauri its variable star designation. The name Pleione originates with Greek mythology; she is the mother of seven daughters known as the Pleiades. In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[7] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[8] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN; which included Pleione for this star. It is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[9]

Visibility

With an apparent magnitude of +5.05 in V, the star is rather difficult to make out with the naked eye, especially since its close neighbour Atlas is 3.7 times brighter and located less than 5 arcminutes away.[note 1] Beginning in October of each year, Pleione along with the rest of the cluster can be seen rising in the east in the early morning before dawn.[10] To see it after sunset, one will need to wait until December. By mid-February, the star is visible to virtually every inhabited region of the globe, with only those south of 66° unable to see it. Even in cities like Cape Town, South Africa, at the tip of the African continent, the star rises almost 32° above the horizon. Due to its declination of roughly +24°, Pleione is circumpolar in the northern hemisphere at latitudes greater than 66° North. Once late April arrives, the cluster can be spotted briefly in the deepening twilight of the western horizon, soon to disappear with the other setting stars.[11]

Pleione is classified as a Gamma Cassiopeiae type variable star, with brightness fluctuations that range between a 4.8 and 5.5 visual magnitude.[12] The SIMBAD astronomical database lists its spectral class as B8IVev,[1] although the current classification recognized by many researchers is B8IVpe.[2][13][14] The suffix "ev" stands for "Spectral emission that exhibits variability" whilst the suffix "pe" refers to "Emission lines with peculiarity". In the case of Pleione, the "peculiar" emissions come from gaseous circumstellar disks formed of material being ejected from the star.

There has been significant debate as to the star's actual distance from Earth. The debate revolves around the different methodologies to measure distance—parallax being the most central, but photometric and spectroscopic observations yielding valuable insights as well.[4][15] Before the Hipparcos mission, the estimated distance for the Pleiades star cluster was around 135 parsecs or 440 light years. However, when the Hipparcos Catalogue was published in 1997, the new parallax measurement indicated a much closer distance of about 119 ± 1.0 pc (388 ± 3.2 ly), triggering substantial controversy among astronomers.[4][16][17] If the Hipparcos estimate were accurate, some astronomers contend, then stars in the cluster would have to be fainter than Sun-like stars—a notion that would challenge some of the fundamental precepts of stellar structure. Interferometric measurements taken in 2004 by the Hubble Telescope's Fine Guidance Sensors and corroborated by studies from Caltech and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory showed the original estimate of 135 pc or 440 ly to be the correct figure.[17] However a recent study published in 2009 has argued otherwise, publishing a new parallax measurement of 8.32 mas with a very tight error factor of 0.13 mas yielding a distance of 120.2 ± 1.9 pc or 392.0 ± 6.0 ly.[4] Which distance estimate future astrometric calculations will corroborate remains to be seen, although the upcoming Gaia mission with its expected launch in late 2012 could well prove to be the ultimate arbiter in this debate.[18]

Properties

In 1942 Otto Struve, one of the early researchers of Be Stars, stated that Pleione is "the most interesting member of the Pleiades cluster".[19] Like many of the stars in the cluster, Pleione is a blue-white B-type main sequence dwarf star with a temperature of about 12,000 Kelvin.[20] It has a bolometric luminosity of 190 L☉ assuming a distance of roughly 120 pc.[5] With a radius of 3.2 R☉ and mass that is 3.4 M☉, Pleione is considerably smaller than the brightest stars in the Pleiades.[5] Alcyone for instance has a radius that is 10 R☉ with a luminosity 2,400 L☉, making it roughly 30 times more voluminous than Pleione and about 13 times brighter.[note 2]

Be star

Pleione is a classical Be star, often referred to as an "active hot star".[20] Classical Be stars are B-type stars close to the main sequence with an "e" added on, signifying that Pleione exhibits emission lines in its spectrum rather than absorption lines, which is what stars usually show.[21] Emission lines usually indicate that a star is surrounded by gas. In the case of a Be star, the gas is typically in the form of an equatorial disk, resulting in electromagnetic radiation that emanates not just from the photosphere, but from the disk as well. The geometry and kinematics of this gaseous circumstellar environment are therefore best explained by a "Keplerian" disk—one that is supported against gravity by rotation rather than gas or radiation pressure.[22][23] Circumstellar disks like this are sometimes referred to as "decretion disks", which is material being actively ejected by the star as opposed to "accretion disks" which involves material falling toward the star.[24]

Be Stars are fast rotators (>200 km/s) with a large stellar wind and high mass loss rate, hence the causative factors behind these gaseous rings.[20] Due to its apparent brightness, the star most recognized for its fast rotation is Achernar, a phenomenon which causes it to be highly oblate. Its rotational velocity, however, of 251 km/s is considerably slower than Pleione's 329 km/s.[6][26] As a result, Pleione actually revolves on its axis once every 11.8 hours compared to Achernar's 48.4 hours.[note 3] The Sun by comparison takes 25.3 days to turn on its axis. Pleione is spinning so fast that it is close to the estimated breakup velocity for a B8V star of about 370–390 km/s.[27] Another Be star whose rotational velocity is extremely fast is Alpha Arae at 470 km/s—a speed so extreme that it is on the verge of exploding.[28]

What makes Pleione particularly unique is that it alternates between three different phases: 1) normal B star, 2) Be star and 3) Be shell star.[5] The cause is likely the surrounding gaseous disk which in many Be stars will appear, then disappear, possibly reforming at a later time. Material in the disc is attracted back towards the star by the pull of gravity, but if it has enough energy it can escape into space, contributing to the stellar wind.[23] Sometimes, Be stars will form multiple gas rings or "decretion disks", each with its own evolution, creating complex circumstellar dynamics.[14]

As a result of such dynamics, Pleione exhibits prominent long-term photometric and spectroscopic variations encompassing a period of about 35 years.[14] In fact, during the last 100 years, Pleione has demonstrated notable phase changes—as a Be phase until 1903, a B phase (1905–1936), a B-shell phase (1938–1954), and another Be phase (1955–1972).[27] It then entered a Be-shell phase in 1972. Then, the star developed many shell absorption lines in its spectrum. At the same time, the star showed a decrease in brightness, beginning at the end of 1971. After reaching the minimum brightness in late 1973, the star gradually brightened. In 1989, Pleione entered a Be phase and stayed as a Be star until the summer of 2005.[14]

The most recent disk responsible for these phase changes was formed in 1972.[14] What's intriguing, however, is that Pleione's long-term polarimetric observations show the intrinsic polarization angle has changed, providing direct evidence for a spatial motion of the disk axis.[29] Because Pleione has a stellar companion with a relatively close orbit, the shift in the polarization angle has been attributed to the companion causing a precession (wobble) of the disk, with a precession period of roughly 81 years.[29]

Recent photometric and spectroscopic observations from 2005 to 2007 indicate that a new disk has formed around the equator—thus constituting a double disk phenomenon with disks at different angles.[14][29] The inclination angle of the new disk is estimated at 60° whereas the previous disk was inclined at around 30°. Such a misaligned double-disk structure has never been observed before among Be stars. Thus, Pleione provides a rare opportunity to investigate the forming process of a new disk and the consequent interaction between the two.[14][29]

Star system

Pleione is known to be a speckle binary, although its orbital parameters have yet to be fully established.[13] In 1996 a group of Japanese and French astronomers discovered that Pleione is a single-lined spectroscopic binary with an orbital period of 218.0 days and a large eccentricity of 0.6.[14][30] The Washington Double Star Catalogue lists an angular separation between the two components of 0.2 arcseconds—an angle which equates to a distance of about 24 AU, assuming a distance of 120 parsecs.[31]

Ethnological influences

Mythology

Pleione was an Oceanid nymph of Mount Kyllene in Arkadia (southern Greece), one of the three thousand daughters of the Titans Oceanus and Tethys.[32][33] The nymphs in Greek mythology were the spirits of nature; oceanids, spirits of the sea.[34] Though considered lesser divinities, they were still very much venerated as the protectors of the natural world. Each oceanid was thence a patroness of a particular body of water — be it ocean, river, lake, spring or even cloud — and by extension activities related thereto. The sea-nymph, Pleione, was the consort of Atlas, the Titan, and mother of the Hyas, Hyades and Pleiades.[35]

Etymology

When names were assigned to the stars in the Pleiades cluster, the bright pair of stars in the East of the cluster were named Atlas and Pleione, while the seven other bright stars were named after the mythological Pleiades (the 'Seven Sisters'). The term "Pleiades" was used by Valerius Flaccus to apply to the cluster as a whole, and Riccioli called the star Mater Pleione.[36]

There is some diversity of opinion as to the origin of the names Pleione and Pleiades. There are three possible derivations of note. Foremost is that both names come from the Greek word πλεῖν, (pr. ple'-ō), meaning "to sail".[36][37] This is particularly plausible given that ancient Greece was a seafaring culture and because of Pleione's mythical status as an Oceanid nymph. Pleione, as a result, is sometimes referred to as the "sailing queen" while her daughters the "sailing ones". Also, the appearance of these stars coincided with the sailing season in antiquity; sailors were well advised to set sail only when the Pleiades were visible at night, lest they meet with misfortune.[35]

Another derivation of the name is the Greek word Πλειόνη[33] (pr. plêionê), meaning "more", "plenty", or "full"—a lexeme with many English derivatives like pleiotropy, pleomorphism, pleonasm, pleonexia, plethora and Pliocene. This meaning also coincides with the biblical Kīmāh and the Arabic word for the Pleiades — Al Thurayya.[36] In fact, Pleione may have been numbered amongst the Epimelides (nymphs of meadows and pastures) and presided over the multiplication of the animals, as her name means "to increase in number".[38]

Finally, the last comes from Peleiades (Greek: Πελειάδες, "doves"), a reference to the sisters' mythical transformation by Zeus into a flock of doves following their pursuit by Orion, the giant huntsman, across the heavens.[39]

Modern legacy

In the best-selling 1955 nature book published by Time-Life called The World We Live In, there is an artist's impression of Pleione entitled Purple Pleione.[40] The illustration is from the famed space artist Chesley Bonestell and carries the caption: "Purple Pleione, a star of the familiar Pleiades cluster, rotates so rapidly that it has flattened into a flying saucer and hurled forth a dark red ring of hydrogen. Where the excited gas crosses Pleione's equator, it obscures her violet light."

Given its mythical connection with sailing and orchids, the name Pleione is often associated with grace, speed and elegance. Some of the finest designs in racing yachts have the name Pleione,[41][42] and the recent Shanghai Oriental Art Center draws its inspiration from an orchid.[43] Fat Jon in his new album Hundred Eight Stars has a prismatic track dedicated to 28 Tauri.[44]

See also

- Lists of stars in the constellation Taurus

- Class B Stars

- Be stars

- Shell star

- Circumstellar disk

Notes

- ↑ The brightness ratio of Atlas versus Pleione is derived from the formula for apparent magnitude and is based on their respective visual magnitudes: Atlas () at 3.62 and Pleione () at 5.05. Therefore:

- ↑ The relative size of Alcyone (VA) compared to Pleione (VP) is determined by comparing their volumes. It is assumed that the volume of each star is reasonably approximated by the formula for a sphere:

- VA ≈ 4⁄3π × 103 ≈ 4,188.79 VSun

- VP ≈ 4⁄3π × 3.23 ≈ 137.26 VSun

- ↑ The time it takes for Achernar (TA) and Pleione (TP) to rotate on its own axis is determined by taking the star's radius in solar units, multiplying by the Sun's radius in kilometers, then calculating the star's circumference at the equator and dividing by its speed of rotation per hour. Therefore:

- TA = 10 R☉ × 696,000 km × 2 × π ÷ 251 km/s ÷ 3,600 ≈ 48.4 hrs

- TP = 3.2 R☉ × 696,000 km × 2 × π ÷ 329 km/s ÷ 3,600 ≈ 11.8 hrs

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "SIMBAD query result: PLEIONE -- Be Star". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- 1 2 Hoffleit; et al. (1991). "Bright Star Catalogue". VizieR (5th Revised ed.). Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

- ↑ Nicolet, B. (1978). "Catalogue of homogeneous data in the UBV photoelectric photometric system.". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 34: 1–49. Bibcode:1978A&AS...34....1N.

- 1 2 3 4 For an in-depth discussion of Pleiades parallax measurements, see section 6.3 of van Leeuwen, F. (2009). "Parallaxes and proper motions for 20 open clusters as based on the new Hipparcos catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 497 (1): 209–242. arXiv:0902.1039

. Bibcode:2009A&A...497..209V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811382.

. Bibcode:2009A&A...497..209V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811382. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kaler, J. B. "PLEIONE (28 Tauri)". University of Illinois. Retrieved 2010-06-11. Kaler acknowledges a distance of 385ly to Pleione, an estimate that is likely derived from the Hipparcos Catalogue published in 1997. Any significant change in astrometric calculations could impact other calculations referenced in this article.

- 1 2 Hoffleit; et al. (1991). "Bright Star Catalogue". VizieR (5th Revised ed.). Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ↑ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ "IAU Catalog of Star Names". Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ↑ Getsova, I.; et al. (2002). "All About The Pleiades". Catch a Star 2002. European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ↑ Bakich, M. E. (22 April 2009). "See Mercury, the Moon, and the Pleiades together in the night sky". Astronomy. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

Don't miss a stunning sight around 9 P.M. local daylight time April 26 when a crescent Moon joins Mercury and the Pleiades in the deepening twilight.

- ↑ "Hipparcos Input Catalogue, Version 2 (Turon+ 1993)". VizieR. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- 1 2 McAlister, H. A.; et al. (1989). "ICCD speckle observations of binary stars. IV - Measurements during 1986-1988 from the Kitt Peak 4 M telescope". Astronomical Journal. 97: 510–531. Bibcode:1989AJ.....97..510M. doi:10.1086/115001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tanaka, K.; et al. (2007). "Dramatic Spectral and Photometric Changes of Pleione (28 Tau) between 2005 November and 2007 April" (PDF). Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 59 (4): L35–L39. Bibcode:2007PASJ...59L..35T. doi:10.1093/pasj/59.4.l35. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

- ↑ Allen, J.; Boyd, P. (15 April 1997). "Finding Stellar Distances". Ask an Astrophysicist. NASA. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

A straightforward summary of the different methods used by astronomers to measure stellar distances.

- ↑ Perryman, M. A. C.; et al. (1997). "The Hipparcos Catalogue". Astronomy and Astrophysics Letters. 323: L49–L52. Bibcode:1997A&A...323L..49P.

The original parallax figure from the Hipparcos Catalogue as shown in the SIMBAD astronomical database was 8.42 ± 0.86mas yielding a distance of about 119 ± 1.0pc or 388 ± 3.2ly

- 1 2 Weaver, D.; Soderblom, D. (1 June 2004). "Hubble Refines Distance to Pleiades Star Cluster". Hubblesite Newscenter. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

- ↑ "Gaia overview". European Space Agency. 4 May 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-14.

- ↑ Struve, O. (1943). "The Story of Pleione". Popular Astronomy. 51: 233. Bibcode:1943PA.....51..233S.

- 1 2 3 Stee, P. "What is a Be star?". Hot and Active Stars Research. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ Plait, P. (5 August 2009). "To B[e] or not to B[e]". Bad Astronomy. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ↑ Porter, J. M.; Rivinius, T. (2003). "Classical Be Stars". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 115 (812): 1153–1170. Bibcode:2003PASP..115.1153P. doi:10.1086/378307.

- 1 2 "Glasgow astronomers explain hot star disks". SpaceRef. 1 November 2002. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ Thizy, O. "Be Stars". Shelyak Instruments. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ "Classical Be Stars". Research in Astronomy & Astrophysics at Lehigh. Lehigh University. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- ↑ "HR 20472". Bright Star Catalogue, 5th Revised Ed. (Hoffleit+, 1991). VizieR, Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- 1 2 Hirata, Ryuko (1995). "Interpretation of the Long-Term Variation in Late-Type Active Be Stars". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 47: 195–218. Bibcode:1995PASJ...47..195H.

- 1 2 Getsova, I.; et al. (20 September 2006). "To Be or Not to Be: Is It All About Spinning?" (Press release). European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 2010-09-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Hirata, R. (2007). "Disk Precession in Pleione". ASP Conference Series. 361: 267. Bibcode:2007ASPC..361..267H.

- ↑ Katahira, Jun-Ichi; et al. (1996). "Period Analysis of the Radial Velocity in PLEIONE". Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. 48: 317–334. Bibcode:1996PASJ...48..317K. doi:10.1093/pasj/48.2.317.

- ↑ Mason, B. D.; et al. (1996). "Pleione". Alcyone (Star Information Tool). Retrieved 2010-09-21.

- ↑ Andrews, M. (2004). The Seven Sisters of the Pleiades - Stories from around the world. Spinifex Press. ISBN 1-876756-45-4. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- 1 2 Smith, W. (1873). "Plei'one". A dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. John Murray. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ↑ Athena, A. (8 July 2010). "Nymphs". Women in Greek Myths. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- 1 2 Apollodorus (1921). "Book 3, Chapter 10, Section 1". The Library. Translated by Frazer, J. G. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- 1 2 3 Allen, R. H. (1963). "Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning". Dover Publications. p. 408. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ↑ Gibson, S. (5 April 2007). "Pleiades Mythology". National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center. Retrieved 2010-06-18.

- ↑ Atsma, A. J. (8 March 2010). "Pleione". Theoi Greek Mythology. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ↑ Hesiod (1914). "ll. 618-640". Works and Days. Translated by Evelyn-White, H. G. The Internet Sacred Text Archive. ISBN 0-585-30250-2. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ↑ Barnett, L. (1955). The World We Live In. Simon & Schuster. p. 284.

- ↑ "Team Pleione". Marblehead International One Design Class. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- ↑ Taylor, J. (19 March 2009). "Fast Boats in the 'Spirit of Tradition'". Jim Taylor Yacht Designs. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- ↑ Chami, C. (9 January 2008). "Paul Andreu - The Oriental Arts Centre in Shanghai". Archinnovations. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- ↑ Hundred Eight Stars at Discogs

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pleione (star). |

- Jim Kaler's Stars, University of Illinois:PLEIONE (28 Tauri)

- Philippe Stee's in-depth information on: Hot and Active Stars Research

- Olivier Thizy's in-depth information on: Be Stars

- High-resolution LRGB image based on 4 hrs total exposure: M45 - Pleiades Open Cluster

- APOD Pictures:

- Orion, the giant huntsman, in pursuit of the Pleiades

- Himalayan Skyscape

- Pleiades and the Milky Way

- Pleiades and the Interstellar Medium