Ranau

| Ranau | |

|---|---|

| District and Town | |

|

Ranau town view. | |

Location of Ranau in Sabah | |

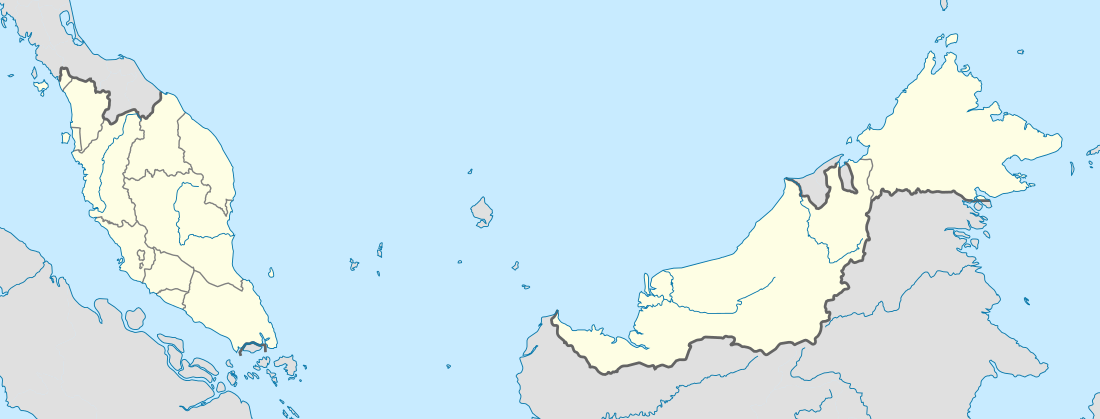

Ranau Location within Malaysia | |

| Coordinates: 5°58′N 116°41′E / 5.967°N 116.683°ECoordinates: 5°58′N 116°41′E / 5.967°N 116.683°E | |

| Country |

|

| State |

|

| Division | West Coast |

| District | Ranau |

| Government | |

| • District Officer | Faimin Kamin |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 3,555.51 km2 (1,372.79 sq mi) |

| Elevation[2] | 1,176 m (3,858.27 ft) |

| Population (2010)[3] | |

| • Total | 94,092 |

| • Density | 26/km2 (68.5/sq mi) |

| Time zone | MST (UTC+8) |

| Postcode[4] | 89307; 89308; 89309 |

| Website | www.sabah.gov.my/pd.rnu |

Ranau (pronounced [ra.naʊ]) is a town as well as a district located in Sabah, Malaysia on the island of Borneo. The landlocked district is situated in the West Coast Division, commencing in the northern part of the Division and continuing in a southerly direction, while bordering the Sandakan Division to the east until it meets the Interior Division border. Ranau sits 108 km (67 mi) east of Kota Kinabalu[5] and 227 km (141 mi) west of Sandakan.[6] As of the 2010 Census, the population of the district was 94,092,[3] an almost entirely Dusun ethnic community.[2][7]

Ranau is noted for its hilly geographical structure and is the largest producer of highland vegetables in the state of Sabah.[8] Tourism and highland agriculture are the major industries, as the district is at 1,176 m above sea level.[2] Its many tourist destinations attracted half a million tourists in 2009.[9] These include Mount Kinabalu (the tallest mountain on Borneo), Kinabalu Park, Poring Hot Springs, Kundasang War Memorial, Death March Trail, Mesilau, and Sabah Tea Garden. Ranau's diverse flora ranges from rich tropical lowland and hill rainforest to tropical mountain, sub-alpine forest and scrub on the higher elevations and particularly abundant in species with examples of flora from as far as China, Australia and the Himalayas, as well as pan-tropical flora.[10]

Kinabalu Park has been recognised by UNESCO as a Center of Plant Diversity for Southeast Asia.[10] In December 2000, the Kinabalu Park was designated by UNESCO as Malaysia's first World Heritage Site.[10]

Ranau was home to the largest mining project in Malaysia, the Mamut Copper Mine,[11] before it ceased operations in 1999.[12] At the peak of its mining activity, Ranau was transformed into a thriving township. The mining company constructed the Ranau Bridge across Liwagu River, the Ranau Golf Course, and also made donations to school building funds, buses, and bus shelters.[13]

History

Toponymy

The origin of the name "Ranau" comes from the Dusun word ranahon, which means paddy fields. The Dusun people who live in the highland grow mountain rice on the hills (called tumo/dumo), where the mountain rice is called parai tidong in Dusun. The people in the lowlands of Ranau use traditional water-filled paddy fields for rice cultivation. Over time, “Ranahon” was shortened to “Ranau.” As the central district administration is nearer to the lowland, the name “Ranau” was adopted as the official name for the district.

Early references

%2C_Malaysia%2C_Sumatra%2C_Borneo_-_Geographicus_-_Siam-ottens-1710.jpg)

Allusions to a place in Ranau, the Mount Kinabalu, had appeared in sources from China. Wang Dayuan mentioned a mountain called Long shan when he described the country of Bo ni (勃泥 bó ní) in his book, Description of the Barbarians of the Isles (島夷誌略 dǎo yí zhì lüè) written between 1330 and 1350.[15] Long shan (龍山 lóng shān) means Dragon Mountain, and the term was associated with Mount Kinabalu because there were dragon legends related to Kinabalu.[16][17] Another Chinese source, a nautical compendium called Fair Winds for Escort (順風相送 shùn fēng xiāng sòng) composed circa 1430, described a voyage from Siam to Mindanao via the west coast of Borneo, where the Chinese ships passed Sheng shan (聖山 shèng shān).[18] Sheng shan which means Holy Mountain, was identified as Mount Kinabalu.[19]

References to Mount Kinabalu had also appeared in early maps of the East Indies made by Europeans cartographers, where it was referred to as Mount St. Pedro or Mount St. Pierre.[20] The name Mount St. Pedro was used by map makers such as Gerardus Mercator in his India Orientalis map published around 1595,[21] Nicolaes Visscher II in his early 17th-century Indiae Orientalis map,[22] and several other cartographers.[23][24][25][26][27] In some maps, for example, the 1710 Ottens's Map of Southeast Asia by Joachim Ottens, the mountain was called Mount St. Pierre.[14] However, John Pinkerton's East India Isles map from 1818 labelled the mountain as St. Peter's Mountain.[28]

Because of the stories of the local people, early geographers believed that there was a great lake at the peak of the mountain.[20] During the Ice age about 100,000 years ago, the mountain was covered with ice sheets and glaciers moved slowly down its slopes. Only the summit peaks were very noticeable above the ice.[29] The natives' oral history may have had its roots in a folk memory of these glistening sheets of ice. The earliest documented expeditions to ascend Kinabalu in March 1851 and in 1858, led by Sir Hugh Low and Sir Spenser St. John, revealed there was no lake.[20]

Later maps, as evident in the maps by Archibald Fullarton & Co.[30] and J.Rapkin,[31] indicated that a lake was located south of the mountain.[20] With further assertions from the Kiau people (of Kota Belud district) that they had done trading business with villagers who lived near the lake shore, St. John thought the lake had probably been located southeast below Kinabalu, where the Ranau plain is situated today.[20] The Dusun word ranahon (ranau) is used to describe a wet field of lowland rice, so highlanders may have thought they were looking at a lake when they saw irrigated rice fields.[32] Explorers William B. Pryer and Captain Francis Xavier Witti concluded there was no lake near Mount Kinabalu when they explored the Ranau plain in the early days.[20][33]

Under British North Borneo Company

During the British North Borneo Company administration beginning in the 19th century, Ranau was governed under the Province Dent.[34] Later it organised as a substation of Tambunan with a Government station under the Interior Residency.[32] Ranau was connected to the West Coast Residency only by a bridle road and by a southerly bridle path 64 km (40 mi) to Tambunan. Telegraph line was also available from Ranau to Tambunan.[35]

The Ranau plain and its surrounding hilly areas were historically inhabited by Dusun farmers who practised shifting cultivation. Their major staple crops were upland rice and lowland wet rice. Natives from Ranau would go to large tamu (native market) at nearby districts to sell and buy, or exchange goods using the barter system.[36] Tobacco, a major export item for the Company,[37] was successfully cultivated in extensive parts of Ranau district, especially in the highlands.[38] It became an important source of income for Ranau natives. At that time, brokers thought that the tobacco produced from highland Ranau and the Interior proper was of high quality compared to that grown down in the lowlands, although the plants were similarly obtained from Ranau.[38]

Between 1897 and 1898, Mat Salleh built a fort in Ranau; he used it as a base three times during his rebellion against the British North Borneo Company. His fort in Ranau was measured at 109 m (119 yd) long and 55 m (60 yd) wide. It had a three-sided strong-point on one side and a watch-tower in the middle. The fort was surrounded by a thick earth wall with high strong fence. Sharp bamboo stakes were thickly sown into the grounds around the fort.[39] Mat Salleh first entered Ranau on 10 February 1897, where he gained many Dusun followers; his influence increased to as far as Inanam. The Company was aware of this development. It attacked his fort in Ranau on 23 February, which resulted in the death of his father.[40] Mat Salleh escaped but retreated back to Ranau in July the same year. After being tracked down by Captain J.M. Reddie and E.H. Barraut, Ranau was attacked again but escaped.[41] Mat Salleh's final movement to Ranau occurred in November 1897.

A total of 288 Sikh, Iban and Dayak policemen from Abai Bay and Sandakan led by G. Hewett, George Ormsby, P. Wise, and Adjutant Alfred Jones, were ordered to invade Mat Salleh's fort in Ranau on 13 December 1897.[41] The fort was significantly destroyed; during the action Jones and 13 other policemen were killed. On 9 January 1898, Hewett and his troops attacked the Ranau fort again, to find it had been abandoned by Mat Salleh and his followers. The government forces destroyed the fort completely.[41] As a result of this rebellion, the Company built an administration building in the district. It erected a "loyalty oath stone" as a sign that the residents of Ranau swore loyalty to the Government.[42] The loyalty oath stone still exists until today.

World War II

The Japanese occupation of North Borneo became official on 16 May 1942, and divided North Borneo into two governorates.[43] Ranau was under the Governorate of the West Coast Territory (西海州 seikaishū) and was directly administered by a district officer (郡長 guncho) with the help of village headmen.[43][44]

At first, the Japanese were not interested in the Interior Residency, but soon, demands for the collection of foodstuffs increased. They also realised the strategic importance of controlling the Interior.[43] The Japanese set up a garrison in Ranau to control the local people; it was one of the strongest army posts in the Interior.[45] Village headmen were given orders to gather as many groups of labourers as possible from villages all over the district, to work for the Japanese in upgrading existing roads, mainly the one leading to Sandakan, and also to construct an airstrip in Ranau near a detention camp of Australian prisoners of war.[45][46] Ranau served as an important junction for the Japanese troops from Sandakan heading to Jesselton and also for the troops from the Interior proper marching as reinforcements towards Kudat.[46]

Towards the end of the war, Ranau stood witness to the infamous Sandakan Death Marches. The first march started in January 1945. 470 Australian prisoners of wars left Sandakan and by June, only 6 remained alive in Ranau. The second march of 536 prisoners began on 29 May 1945. Along the way, two prisoners managed to escape into the jungle and later saved by the Allied units with the help of locals. Only 183 prisoners reached the Ranau camp on 24 June 1945. Another four prisoners successfully fled the camp and led to safety by a native teenager who found them hiding in the jungle along a river.[47] They were also rescued by Allied paratroopers later. In June 1945, the Japanese captors moved with the prisoners 8.3 km (5.2 mi) south of Ranau to a second jungle camp near the Kenipir River to escape from the air raids of napalm bombs by the Allied planes. By August 1945, all survivors of the marches were killed.[48]

Three memorials were erected in remembrance of the marches. The Ranau Memorial, also known as the Gunner Cleary Memorial was constructed in 1985 in memory of the tragic death of Gunner Albert Neil Cleary from the first Death March.[49] The Kundasang War Memorial built in 1962 is a memorial park dedicated to the Australian and British servicemen who died in Sandakan and on the marches, and also to the locals who assisted the prisoners of wars.[50] The Last Camp Memorial was newly unveiled in 2009 in remembrance of the exact spot where the Death March ended.[51]

Geography

Ranau is situated between 5°30’N to 6°25’N and 116°30’E to 117°5’E.[1] The district, with a total area of 3,555.51 km2 (1,372.79 sq mi),[1] is surrounded entirely by Kota Marudu to the north, Kota Belud to the northeast, Tuaran to the west, Tambunan to the southwest, Keningau to the south, Tongod to the southeast, and Beluran to the east.[52] The northern part of Ranau is bounded by the Crocker Range and the Pinousok summit which runs in a southwesterly direction, to the east lies the Ranau plain and Trus Madi Range while the southern part is bounded by the Labuk highlands.[1] Laconically, Ranau's geography is characterised by undulating lands at most areas with a valley plain.[1]

Demographics

| Ranau Demographics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 Census[7] | Ranau proper | Kundasang | Remainder of Ranau district |

| Total population | 8,970 | 5,008 | 80,114 |

| Kadazan-Dusun | 6,487 | 3,457 | 70,230 |

| Malay | 352 | 129 | 479 |

| Bajau | 250 | 143 | 696 |

| Murut | 37 | 7 | 97 |

| Other Bumiputera | 764 | 188 | 2,807 |

| Chinese | 670 | 133 | 718 |

| Indians | 24 | 3 | 32 |

| Others | 98 | 74 | 548 |

| Non-Malaysian citizens | 288 | 856 | 4,513 |

| Year | Population | %± |

|---|---|---|

| 2000[53] | 70,649 | - |

| 2010[3] | 94,092 | +33.2 |

According to the 2010 Census, there were 94,092 people residing in the district, with 14,207 households and 15,514 living quarters.[54] The population density was 26 people per km² (68.5/ sq mi).

The racial makeup of the district consisted of 93.1% Kadazan-Dusun, 1.7% Chinese, 1.16% Bajau, 1.0% Malay, 0.15% Murut, 0.1% Indians, 4% Other Bumiputera and 0.8% listed as Others.[7] 6.0% were Non-Malaysian citizens, mainly foreign workers from Indonesia and the Philippines working as labours in large farms and plantations.[3]

In the district the population was spread out with 48,341 male residents (51.4%) and 45,751 female residents (48.6%)[54] out of which 39.1% under the age of 15, 20.1% from 15 to 24, 25% from 25 to 44, 11.8% from 45 to 64, and 3.9% who were 65 years of age or older.[55] For every 100 females there were 106 males.[3]

Most Ranau residents speak the Sabahan Malay dialect but the Dusun language is primarily spoken as well especially among the older generations. Mandarin and Chinese dialects such as Hakka and Hokkien are spoken among the Chinese community and native languages of the other ethnicities can be heard as well. English is more or less spoken and understood by the younger generations and the locals who work in the professional sectors.

As of 2000,[53] 46.85% of the population practised Islam. Closely behind, Christians made up 45.68% of the population while 1.09% were Buddhists and 0.06% were Hindus. 6.31% were recorded as “Others”, presumably referring the remaining natives who still practice ancestral animistic beliefs and traditions.

Major Places of Worship

- Mosque

- Ar-Rahman Mosque (Masjid Jamek Ar-Rahman).

- Temple

- Churches

- Catholic Church of St. Peter Claver Ranau.

- Ranau Basel Christian Church of Malaysia.

- Ranau Town Sidang Injil Borneo (SIB) Church.

- St. Paul’s Anglican Church.

- Seventh-day Adventist Church.

- True Jesus Church.

- GPI Church (Gereja Perkhabaran Injil).

The Basel church, the Chinese temple and the mosque are located next to each other along the same road called Mosque Road (Jalan Masjid).

Administrative divisions

| Ranau Sub-districts and Villages

Liwogu Pekan Ranau, Kimolohing, Muhibbah, Paka II, Longut Baru, Kiaburi, Rapak/Takurik, Lintuhun, Lingkudau Lama, Lingkudau Baru, Tiang Baru, Kasiladan/Giman/Kawog, Kandawayon, Mininsalu Baru Tanah Rata/Kituntul Lukapon, Togudon Baru, Sinarut, Lasing, Marakau, Kilimu, Tanah Merah, Bahab, Libang, Kokob Baru, Tudangan, Matan, Silou, Badukan, Boduyon, Kituntul Lama, Kituntul Baru,Togoyog/Lipoi, Kinapulidan, Mindohuon Baru, Rugading, Kigiuk Tambiau/Mohimboyon Kibbas, Purakagis, Koporingan, Tambiau, Sarapong, Paka I,Toboh Baru, Liposu Baru, Liposu Lama, Wa'ang, Kiwawoi, Mohimboyon Suminimpod/Kopongian Gana-Gana, Kopongian, Giring-Giring, Nampasan Lama, Gaur, Suminimpod, Mininsalu Lama/Narambai, Niasan, Bayag, Kita'i, Longut, Tiang Lama Kundasang/Bundu Tuhan Pinousuk, Tambalang, Ruhukon, Sinisian, Somuruh, Naradau, Desa Aman, Lembah Permai, Dumpiring Bawah, Kinoundusan, JKDB Pekan Kundasang, Dumpiring Atas, Kinasaraban, Kundasang Lama, Cinta Mata, Kalangaan, Kouluan, Mosilou, Sokid Bundu Tuhan, Siba Bundu Tuhan, Gondohon Lohan/Bongkud Lohan Ulu, Karanaan Baru, Kinasaraban Baru, Lohan Skim I, Minihas/Maukab Baru, Rondogung Baru, Kinorotuan, Silad, Lohan Skim II, Simpangan Poring, Nampasan Baru, Poring, Nopung I, Nopung II, Narawang, Namaus, Bongkud, Lutut, Waluhu Rondogung Mumpait, Kinarasan, Poropot, Rondogung, Lagkau, Kosisingon, Tungou, Sumalang, Maukab Pirancangan Singgaron Baru, Togis, Pirancangan, Dobut Langsat, Tokutan, Langsat, Nalumad, Kilanas Baru, Kirokot Nalapak Sodul I, Sodul II, Muruk, Luanti Baru, Nalapak, Kobuh Baru, Nobutan, Sungangon, Sagindai Baru, Sagindai Lama Karanaan/Togudon Karanaan, Sosondoton, Komburongoh/Mogoho/Soyod, Piasau, Togudon Lama/Pulutan, Himbaan, Pahu, Ratau, Torolobou, Tinatasan, Toboh Pahu, Toboh Lama, Tudan I,Tudan II Timbua Tarawas, Pinawantai, Pahu Pinawantai, Dobut Timbua, Kimboroi Timbua, Timbua, Lobou Baru, Togop Laut, Tinutuan, Togop Darat, Morungin I, Lobou Timbua, Morungin II, Pinampadan, Tibabar, Turuntungan, Monggis, Tumbalang, Lobou Lama, Daramakon, Koiyop, Nawanon, Kantas Baru, Pugi Paginatan Matupang, Torikon/Tadsom, Minihas, Paginatan, Bunakon, Lungkidau, Soborong Paginatan, Maringkan, Balisok, Tabah, Nunuk Ragang, Toupus, Miruru, Mangkadait, Mindohuon Lama, Toporoh, Mantapok, Tompios Molinsou Mokodou, Kopuakan, Tanid, Linapasan, Malinsou Darat / Nasakot, Sumbilingon, Wayan, Tinindoi, Sinurai, Mangkapoh I, Tinaum/Mangkapoh II, Mampakot/Molinsou Kaingaran Paka Sugut, Moningkulau, Kawiyan, Kilanas Sugut, Giring, Pinutudaan/Minintob, Kaingaran, Kotog, Moridi, Botong, Tinongian, Namaus, Ulu Sugut, Kiwakau, Karagasan, Pamaitan, Patau, Tundangon Ulu Sugut, Mansalu, Gan, Gusi |

|---|

In the national and state level, Ranau has only one parliamentary seat for the Dewan Rakyat (House of Representatives) which is P.179 Ranau but it is represented by three state assemblymen in the Sabah State Legislative Assembly, each one for N.29 Kundasang, N.30 Karanaan and N.31 Paginatan state assembly seats respectively.

As of the 13th General Election held on 5 May 2013, the current Member of Parliament for Ranau is Datuk Dr. Ewon Ebin[56] and the current state assemblymen representing the district are Datuk Dr. Joachim Gunsalam for N.29 Kundasang,[57] Datuk Seri Panglima Haji Masidi Manjun for N.30 Karanaan[58] and Datuk Siringan Gubat for N.31 Paginatan.[59]

Meanwhile, in the district level, Ranau is governed under a district office form of local government headed by a District Officer. Since 2009, the District Officer of Ranau is Haji Faimin Kamin. There is only a Magistrates’ Court in the district but there is also a Native Court, having jurisdiction on matters of native law and custom.

Normally, each village will have a Village Head working as a leader, together with a Village Development and Safety Committee carrying out activities pertaining to the villagers’ interests.

Ranau district is divided into 14 sub-districts and each sub-district is divided into villages (Malay: kampung, abbreviation: kg.). There are a total of 212 villages in Ranau. The following are the 14 sub-districts in Ranau with its respective villages in order of proximity to Ranau township:

Economy

Ranau is an important agricultural and tourism center in Sabah and this two sectors have been the main economy backbone for the district. Most of the tourism business are centred around the highlands of Kundasang, a sub-district in Ranau while agriculture business is widespread all over Ranau. Therefore, most people of Ranau work as farmers or operators of their own business although there are white-collar workers as well mainly in the government sectors such health, education, service and administration and a few in the banking sector.

Agriculture

The moderate temperature of the Ranau highlands coupled with its fertile soil has been fully utilised by farmers to grow different types of vegetables and fruits such as cabbage, spring onion, tomato, lettuce, carrot and to a certain extent cauliflower, capsicum and many others. Strawberry has been successfully cultivated here and there were attempts in growing apple as well although the result has been varying. Flowers of different species are also planted here for commercial purposes.

Kundasang also boasts a dairy farm owned by Desa Cattle (Sabah) Sdn. Bhd company located at Mesilau.

Tourism

Hotels, resorts, motels and lodging houses can be found concentrated nearer to the Kinabalu Park. Not only do these facilities improved the growth of tourism business by attracting more visitors to stay longer but the local residents have also benefited as more jobs have been created for them.

Among the well-known hotels in Kundasang are the Mount Kinabalu Heritage Resort & Spa and Kinabalu Pine Resort. A new 5-star hotel called the Royal Kinabalu Mountain Resort & Hotel Suites located 800 meters from the entrance of Kinabalu Park is currently undergoing construction.[60]

During weekends and school holidays, lots of tourist buses and vans plus private cars from Sarawak and Brunei can be seen heading to Ranau.

Other business

Apart from that, other business such as restaurants, superstores such as Milimewa and G-Mart, grocery shops, clothing stores, handphone shops and cyber cafes are mainly operated within the township area. CIMB Bank, Maybank, Agro Bank, Bank Rakyat and Bank Simpanan Nasional each have their branch in Ranau. The only fast food restaurant in Ranau is KFC.

Education

All primary schools and secondary schools in Ranau are public schools although a small private school for secondary school students does exist and a number of privately owned kindergartens as well. The Ranau District Education Office provides services to 11 national secondary schools and 71 national primary schools.[61]

The only Chinese National-type school in Ranau is the Ranau Pai Wen National-type (Chinese) Primary School (Chinese: 兰瑙培文小学; pinyin: lán nǎo péi wén xiǎo xué). There are two schools with Christian missionaries background, St. Benedict's Ranau National Primary School in the town area and Don Bosco Bundu Tuhan National Primary School in Bundu Tuhan. Apart from the typical primary schools, there are also Islamic religious primary schools that cater to Islamic education for primary students. For Islamic religious secondary school, there are only two such schools in the district, i.e. the SMA Mohammad Ali Ranau in Lohan and SMA Al-Irsyadiah Marakau Ranau in Marakau.

The oldest national secondary school in Ranau is Mat Salleh Ranau National Secondary School while the oldest primary school is Ranau Town National Primary School. Among the newly built schools in Ranau are Ranau National Secondary School and Kilimu National Primary School.

Secondary schools in Ranau

|

|

Secondary school leavers can also opt to take vocational courses at the Ranau MARA Vocational Center (Pusat Giat MARA Ranau). There is also a bible school; Maktab Teologi Sabah (Sabah Theology School) located in Namaus which offers up until degree level programs.[62]

Sport & Recreation

Ranau Sports Complex (KSR)

Ranau Sports Complex is located at an altitude of 780 m above the sea level and surrounded by hills. The chilly climate engulfing the sports complex makes the place very suitable as a training ground for all sports.[63]

Ranau Recreation & Golf Club (RRGC)

RRGC located at Kilometer 1, Jalan Ranau - Tambunan, Ranau, Sabah. 9 hole golf course with panoramic view of the imposing Mount Kinabalu. With state of the rolling fairways and green are difficult to read, it could test the strategy of golfers. Some players say, it is a 9-hole golf course is the best in the state. The club was joined by some of the best clubs around. With a total length of 5.737 meters for men and 5.053 meters for lady. Course rating : Par 72. Slope Rating : 128 (Men) / 118 (Lady).

Culture

A number of festive celebrations observed by Ranau people can be seen celebrated throughout the year, be it religious or cultural celebrations and among them, the major ones are Tadau Kaamatan (Harvest Festival), Eid ul-Fitr, Christmas, and Chinese New Year.

Tadau Kaamatan is an annual event celebrated by the Dusun people in Ranau district in the month of May although the exact date is subject to change each year but as with any district level Kaamatan celebration, the date precedes the Sabah state level Kaamatan celebration which falls on 30 and 31 May every year. However, it is interesting to note that, at village level, the Kaamatan may be celebrated as late as June or July depending on their own preferences.

Originally a ritualistic event, Kaamatan was usually marked by strict observance of animistic rituals and rites to be performed to appease the spirit of rice at the end of the harvesting season. Nevertheless, today, Kaamatan is more akin to Thanksgiving as the majority of Dusun people have converted to mainstream religion although some still practice the rituals and rites but rarely to be seen. Among the highlights of Kaamatan events which usually attract the most people are Sugandoi (singing competition) and Unduk Ngadau (cultural beauty queen pageant) while traditional sports competitions are also held.

During Eid ul-Fitr, open houses are the norm, with Ranau people, regardless of religion, visiting the houses of their Muslim relatives and friends to mark the celebration. Like many other Christians in Asia, Christmas is still being observed in a religious fashion where churches usually hold congregation throughout the Christmas week with the highlights on Christmas Eve and Christmas Mass. Carolling can also be seen done among the younger generations although they only visit houses where they are invited to carol. Open houses and Mass, usually by the Ranau Council of Churches where different Christians denominations celebrate together and by Christian politicians can also be seen.

Chinese New Year is celebrated mainly by the Chinese community and during the week of the celebration, one can hear and watch the Ranau Lion Dance team visiting Chinese peoples' houses throughout the Ranau town and its vicinities to perform the dance accompanied by its trademark musical instrument performance of drums, cymbals and gongs as well.

Other celebration includes the Good Friday where one would normally see the Christians in the district going to church congregations during the Holy Week with its culmination is on Good Friday to Holy Saturday and usually ends on Easter Sunday. Meanwhile, another religious celebration that can be observed here is the Eid al-Adha.

Notable residents

- Government and politics

- Tan Sri Haji Abdul Ghani Gilong – Former Federal Minister of Sabah Affairs (June 1968 - May 1969), Federal Minister of Justice (5 May 1969 - September 1970), Federal Minister of Transport (September 1970 - 1974), Federal Minister of Works & Power, Transport & Utilities (1968–1978)[64]

- The Late Datuk Mark Koding – Former Sabah Deputy Chief Minister-cum-Minister for Industrial & Rural Development (April 1985 - 1988). Founder President, AKAR (1988–1997)[65]

- Tan Sri Datuk Seri Panglima Kasitah Gaddam – Founder member and Vice-President, PBS (1985–1990). Appointed senator, Parliament of Malaysia (1999). Federal Minister of Land & Co-operative Development (1999–2004)[66]

- Datuk Haji Masidi Manjun – Sabah Minister of Tourism, Culture and Environment (current)

- Datuk Dr. Ewon Ebin – Ranau MP (current),[56] Former Federal Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation (May 2013 - July 2015)[67]

- Datuk Dr. Joachim Gunsalam – Sabah Assistant Minister of Local Government and Housing (current)

- Datuk Abidin Madingkir –Kota Kinabalu City Mayor (2011-2016)[68]

- Datuk Matius Sator – Permanent Secretary to the Sabah Local Government and Housing Ministry (current)[69]

- Datuk Siringan Gubat – Sabah Minister of Resource Development and Information Technology (current)

- Dato' Sri Dr. Hasan bin Abdul Rahman – Former Director-General of Health (2011–2012)

- Sports

- Danny Kuilin, Saffrey Sumping – Malaysia's top mountain runners, 2010 Skyrunner World Series[70]

- Entertainment

- Nazrey Johani – Past member of Raihan, a nasheed group

- Linda Nanuwil – Singer, first runner-up in Akademi Fantasia Season 2

- Siti Adira Suhaimi – Singer, first runner-up in Akademi Fantasia Season 8

Friendship district

-

Longmen County, Huizhou, China (since 10 October 2011)[71][72]

Longmen County, Huizhou, China (since 10 October 2011)[71][72]

Notes

- References

- 1 2 3 4 5 (Malay) "Background of Ranau district". Ranau District Office. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Destinations: Places To Go - Ranau". Sabah Tourism Board. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Total population by ethnic group, administrative district and state, Malaysia, 2010" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ↑ "Postcode Finder". Pos Malaysia. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ↑ (Malay) "Location Background of Ranau". Ranau Education Office. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ "Distance from Ranau to Sandakan". Google Maps. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 Department of Statistics, Malaysia. (December 2011). "Table 11.1: Total population by ethnic group, Local Authority area and state, Malaysia, 2010 (p. 137). Population Distribution by Local Authority Areas and Mukims, 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2012

- ↑ "Ranau meteorological station to start operations in January". The Borneo Post. 8 November 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ (Malay) "More Than Half A Million Tourists Visited Ranau Last Year". Kadazandusun Cultural Association. 3 June 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Kinabalu Park". World Heritage Center, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ Mamut Copper Mining Sdn. Bhd. 1996, p. 6

- ↑ Chiew, Hilary. 2 October 2007. "Poisonous wasteland". The Star, Retrieved 6 February 2012.

- ↑ Mamut Copper Mining Sdn. Bhd. 1996, p. 24

- 1 2 "Le Royaume de Siam avec Les Royaumes Qui Luy sont Tributaries & c. - La Royaume de Siam avec les royaumes qui luy sont Tributaires, et les Isles de Sumatra, Andemaon, etc. Et les Isles Voisine Aven les Observations des Six Peres Jesuites Envojez par le Roy en Qualite de Ses Mathe : maticiens dans les Indes, et a laChine ou est aussi Tracee. La Route Qu'ils ont teniie par le Destroit de la Sonde Jusqu a Siam". Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ Nicholl, Robert. (1980), "Notes on Some Controversial Issues in Brunei History", Archipel 19: 27-28

- ↑ Ling Roth H., Native of Sarawak & British North Borneo, 1, London (1896) & Singapore (1968): 304-305

- ↑ Sweeney, Amin. (1968), Silsilah Raja-raja Berunai, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 41(2): 52

- ↑ Mills, J.V.. (1979), "Chinese Navigators in Insulinde about A.D. 1500", Archipel 18: 81

- ↑ Mills, J.V.. (1979), "Chinese Navigators in Insulinde about A.D. 1500", Archipel 18: 79

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rutter 1922, p. 22

- ↑ "India Orientalis", Goetzfried Antique Maps, Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "Indiae Orientalis". Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "Borneo Insula". Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "De Agtste Oostindize Reys voor d'Engelze Maatschappie onder Kapitein Ioan Saris, gedaan ne Iava, de Moluccos en Iapan". Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "Les Isles De Sonde". Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "A General Map of the East Indies and that Part of China where the Europeans have any Settlements or Commonly any Trade". Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "Isole Filippine, Ladrones, e Moluccos o Isole della Speziarie come anco Celebes &c.". Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps Inc.. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "East India Isles".Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ Phillips & Liew 2005, p. 8

- ↑ "Indian Archipelago Compiled From the Various Surveyas of the British & Dutch Governments And Other Materials In The Possession of the Royal Geographical Society". David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "Malay Archipelago, Or East India Islands". David Rumsey Historical Map Collection. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- 1 2 Rutter 1922, p. 47

- ↑ Pryer 1893, p. 27

- ↑ R. Evans 1999, p. North Borneo Map — 1905

- ↑ Rutter 1922, p. 398

- ↑ Rutter 1922, p. 367

- ↑ British North Borneo Company 1899, p. 27

- 1 2 Rutter 1922, p. 253

- ↑ Rutter 1922, p. 194

- ↑ Osman, Ali & B.Basrah Bee May 2007, p. 14

- 1 2 3 Osman, Ali & B.Basrah Bee May 2007, p. 17

- ↑ Osman, Ali & B.Basrah Bee May 2007, p. 19

- 1 2 3 R. Evans 1999, p. 30

- ↑ (Japanese)"100年前のコタキナバル". 愛するマレーシア、ボルネオ島でセカンドライフ. 22 June 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- 1 2 R. Evans 1999, p. 36

- 1 2 R. Evans 1999, p. 42

- ↑ "Windows To Sandakan". ABC1. 19 April 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Where the Death March ended". Daily Express. 23 August 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Ranau Memorial At Sabah Malaysia". The Borneo POW Story. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Kundasang War Memorial Sabah Malaysia". The Borneo POW Story. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Ranau: The Last Camp Memorial". Lynette Ramsay Silver. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ Department of Statistics, Malaysia. (December 2011)."Map showing administrative district boundary and local authority area" (p. 153). Population Distribution by Local Authority Areas and Mukims, 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- 1 2 (Malay) “Population distribution of Ethnicity and Religion”. Ranau District Office. Retrieved 5 February 2012

- 1 2 Department of Statistics, Malaysia. (December 2011). "Table 11.3: Total population by sex, households and living quarters, Local Authority area and state, Malaysia, 2010 (cont'd) (p. 150). Population Distribution by Local Authority Areas and Mukims, 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2012

- ↑ Department of Statistics, Malaysia. (December 2011). "Table 11.2: Total population by age group, Local Authority area and state, Malaysia, 2010 (cont'd) (pp. 143-144). Population Distribution by Local Authority Areas and Mukims, 2010. Retrieved 5 February 2012

- 1 2 (Malay) "13th General Election Results for P.179 Ranau Parliamentary Seat", PRU ke-13 Online Official Portal. Retrieved on 11 May 2013.

- ↑ (Malay) "13th General Election Results for N.29 Kundasang State Seat", PRU ke-13 Online Official Portal. Retrieved on 11 May 2013.

- ↑ (Malay) "13th General Election Results for N.30 Karanaan State Seat", PRU ke-13 Online Official Portal. Retrieved on 11 May 2013.

- ↑ (Malay) "13th General Election Results for N.31 Paginatan State Seat", PRU ke-13 Online Official Portal. Retrieved on 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Royal Kinabalu Mountain Resort & Hotel Suites Official Website"

- ↑ (Malay) "Statistics of Students, Teachers, Non-teacher Staffs and Classes". Ranau District Education Office. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ↑ "Quarterly Report on Sabah Project - December 2008". Sidang Injil Borneo Kuala Lumpur.

- ↑ "The Facts of Altitude Training in Ranau, Sabah". www.adriansprints.com. 18 February 2011. Retrieved on 20 May 2011

- ↑ Koy et al. 2007a, p. 714

- ↑ Koy et al. 2007b, p. 1245

- ↑ Koy et al. 2007a, p. 903

- ↑ "Malaysian Cabinet Reshuffle 2015 - Who's in, who's out". Astro Awani. Putrajaya. 29 July 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ↑ "Abidin is KK's third Mayor", Daily Express. Kota Kinabalu. 1 February 2011. Retrieved on 30 April 2011.

- ↑ "Sabah Local Government and Housing Ministry Official Website"

- ↑ "Runners do country proud in marathon". New Straits Times. Kota Kinabalu. 23 September 2010. Retrieved on 28 September 2010.

- ↑ "Ranau, China county become friendship districts", The Borneo Post, 8 November 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ↑ (Chinese) "龙门与马来西亚兰瑙县签署缔结友好县备忘录". Longmen County News Center. 11 October 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Bibliography

- Department of Statistics, Malaysia (December 2011). Population Distribution by Local Authority Areas and Mukims, 2010. Retrieved February 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Mamut Copper Mining Sdn. Bhd. (1996). A Responsible Approach To Resource Development. Paragraphics.

- Koy, R.M.S.; S. Koroh, D.; Koy, A.K.L.; Koy, L.T.L.; Koy, D.T.F (2007a). Malaysia's Who's Who - 2007. 1. Kuala Lumpur: Kasuya Management. p. 714. ISBN 978-983-9624-05-2.

- Koy, R.M.S.; S. Koroh, D.; Koy, A.K.L.; Koy, L.T.L.; Koy, D.T.F (2007b). Malaysia's Who's Who - 2007. 2. Kuala Lumpur: Kasuya Management. p. 1245. ISBN 978-983-9624-05-2.

- Rutter, Owen (1922). British North Borneo: An Account of its History, Resources and Native Tribes. Great Britain: Constable. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Phillips, Anthea; Liew, Francis (2005). Kinabalu Park: Sabah, Malaysian Borneo. United Kingdom: New Holland. ISBN 1-84330-359-0.

- British North Borneo Company (1899). Views of British North Borneo Company With A Brief History Of The Colony. London: William Brown. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Pryer, W.B. (1893). A Decade In Borneo. London: Hutchinson. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Osman, Prof. Dr. Sabihah; Ali, Dr. Ismail; B. Basrah Bee, Baszley Bee; et al. (May 2007). Datu Paduka Mat Salleh, Pahlawan Sabah (Hero of Sabah)(1894-1900). Sabah State Archives.

- R. Evans, Stephen (1999). Sabah (North Borneo) Under The Rising Sun Government. Malaysia. ISBN 978-983-3987-24-5.

External links

General

- (Malay) Ranau District Office Website

Tourism

- Desa Cattle Facebook Page

- Kinabalu Pine Resort

- Mount Kinabalu Heritage Resort & Spa

- Ranau Recreation & Golf Club (RRGC)

|

Kota Belud | Kota Marudu |  | |

| Tuaran | |

Beluran | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Tambunan | Keningau | Tongod |