Robert Stone (novelist)

| Robert Stone | |

|---|---|

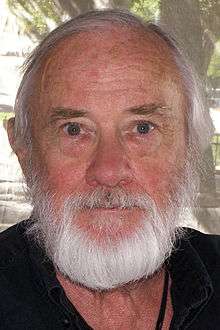

Robert Stone at the 2010 Texas Book Festival. | |

| Born |

August 21, 1937 Brooklyn, New York, United States |

| Died |

January 10, 2015 (aged 77) Key West, Florida, United States |

| Occupation | Author, journalist |

| Literary movement | Naturalism, Stream of consciousness |

| Notable works | Dog Soldiers |

| Notable awards | National Book Award 1975 |

Robert Stone (August 21, 1937 – January 10, 2015) was an American novelist.

He was twice a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and once for the PEN/Faulkner Award.[1][2][3][4] Stone was five times a finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction,[5] which he did receive in 1975 for his novel Dog Soldiers.[6][7] Time magazine included this novel in its list TIME 100 Best English-language Novels from 1923 to 2005.[8] Dog Soldiers was adapted into the film Who'll Stop the Rain (1978) starring Nick Nolte, from a script that Stone co-wrote.[9]

During his lifetime Stone received material support and recognition including Guggenheim[10] and National Endowment for the Humanities fellowships, the five-year Mildred and Harold Strauss Living Award, the John Dos Passos Prize for Literature, and the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters Award. Stone also offered his own support and recognition of writers during his lifetime, serving as Chairman of the PEN/Faulkner Foundation Board of Directors for over thirty years.[11]

Stone's best known work is characterized by action-tinged adventures, political concerns and dark humor. Many of his novels are set in unusual, exotic landscapes of raging social turbulence, such as the Vietnam War; a post-coup violent banana republic in Central America; Jim Crow-era New Orleans, and Jerusalem on the verge of the millennium.[12]

Life

Robert Stone was born in Brooklyn, New York to a "family of Scottish Presbyterians and Irish Catholics who made their living as tugboat workers in New York harbor."[13] Until the age of six he was raised by his mother, who suffered from schizophrenia; after she was institutionalized, he spent several years in a Catholic orphanage. In his short story "Absence of Mercy", which he has called autobiographical,[14] the protagonist Mackay is placed at age five in an orphanage described as having had "the social dynamic of a coral reef".

The battered protagonists and "harrowing creations" in Stone's fiction often transmit a "mix of gloom and bleak irony" that would seem to come from Stone's personal experience: he had a difficult upbringing (besides his mother's schizophrenia, his father abandoned Stone's mother soon after his birth)[15] and Stone had his share of struggles with alcohol and drugs.[16] He was kicked out of a Marist high school during his senior year[17] for "drinking too much beer and being 'militantly atheistic' " and didn't graduate.[13] Soon afterwards, Stone joined the Navy for four years. At sea he traveled to many remote places, including Antarctica and Egypt. But according to Stone, it was his first shore leave in a pre-Fidel Castro era Havana, Cuba that left a mark on him in terms of its lasting impact on Stone's future writing:

"Havana was my first liberty port, my first foreign city. It was 1955 and I was 17, a radio operator with an amphibious assault force in the U.S. Navy ... At the time, I was struck less by the frivolity of Havana than by its unashamed seriousness ... All this Spanish tragedy, leavened with Creole sensuality, made Havana irresistible. Whether or not I got it right, I have used the film of its memory ever since in turning real cities into imaginary ones."[13]

Stone had many nautical experiences that would shape his creative imagination, some of these described in his memoir Prime Green, published in 2007. These first-hand experiences would at times turn violent: Stone witnessed the French Army bombing Port Said.

In the early 1960s, he briefly attended New York University; worked as a copy boy at the New York Daily News; married and moved to New Orleans; and attended the Wallace Stegner workshop at Stanford University, where he began writing a novel. Although he met the influential Beat Generation writer Ken Kesey and other Merry Pranksters, he was not a passenger on the famous 1964 bus trip to New York, contrary to some media reports.[18] Living in New York at the time, he met the bus on its arrival and accompanied Kesey to an "after-bus party" whose attendees included a dyspeptic Jack Kerouac.[19]

Stone taught in the creative writing programs at various university programs around the United States. He was at Johns Hopkins University Writing Seminars from 1993–1994 and subsequently at Yale University. For the 2010–2011 school year, Stone was the Endowed Chair in the English Department at Texas State University-San Marcos. He was also active in many of the writing seminars in and around Key West, Florida[13] where he resided during the winter months.[17] Stone was appointed an honorary director of the Key West Literary Seminar serving in that capacity during the final decade of his life.[20]

At age 72, just after the publication of his second short-story collection Fun With Problems, Stone admitted (during a newspaper interview) that he suffered from severe emphysema: "It's my punishment for chain-smoking," he says. But with a wry laugh, he recalls his reaction to being told of the harm smoking could cause him in old age: "I'm not going to know I'm alive!".[16]

According to his literary agent, Stone died from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on January 10, 2015 in Key West,[21] where he and his wife had spent their winters for more than twenty years.[22] At the time of his death, Stone was survived by his wife (of 55 years) Janice and their two (adult-age) children[23] daughter Deirdre and son Ian.[17]

Fiction

Stone's first novel, A Hall of Mirrors, appeared in 1967.[24] It won both a Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship, and a William Faulkner Foundation Award for best first novel. Set in New Orleans in 1962 and based partly on actual events, the novel depicted a political scene dominated by right-wing racism, but its style was more reminiscent of Beat writers than of earlier social realists: alternating between naturalism and stream of consciousness. It was adapted as a film, WUSA (1970) based on Stone's screenplay of his own novel.[25] The novel's success led to a Guggenheim Fellowship and began Stone's career as a professional writer.

In 1971 he traveled to Vietnam as a correspondent for an obscure British journal called "Ink".[26] His time there served as the inspiration for his second novel, Dog Soldiers (1974), which features a journalist smuggling heroin from Vietnam. It shared the 1975 U.S. National Book Award with The Hair of Harold Roux by Thomas Williams.[6][27]

Stone's third book, A Flag for Sunrise (1981), was published to unanimous critical praise and moderate commercial success. The story follows a wide cast of characters as their paths intersect in a fictionalized banana republic based on Nicaragua. The novel was a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction and the Pulitzer Prize.[1][3] A Flag for Sunrise was twice a finalist for the National Book Award, once following its hardcover release and again the next year when it was reissued in paperback.[28][29]

In contrast to the grand, somewhat satirical adventure epics Stone is commonly associated with, his next two novels were smaller-scale character studies: the misfortunate tale of a Hollywood movie actress in Children of Light, and an eccentric at the midst of a circumnavigation race in Outerbridge Reach (based loosely on the story of Donald Crowhurst), published in 1986 and 1992 respectively. The latter was a finalist for the National Book Award for 1992.[30]Bear and His Daughter, published in 1997, is a short story collection that lost the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction to American Pastoral by Philip Roth.[2]

Stone returned to the complex political novel with Damascus Gate (1998), about a man with messianic delusions caught up in a terrorist plot in Jerusalem. The novel was a finalist for the National Book Award for 1998.[31] It was followed in 2003 by Bay of Souls. The final novel that Stone published in his lifetime was Death of the Black-Haired Girl which appeared in 2013.[32]

Nonfiction

Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties (2007) is Stone's memoir discussing his experiences in the 1960s counterculture.[22] "Pleasant goofing" was the way Stone described those days in a Washington Post interview from 1981.[13] This autobiographical work begins with his days in the Navy and ends with his days as a correspondent in Vietnam. Besides Ken Kesey, this work features Stone's insights on Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Kerouac from his time spent traveling with them.[33] Prime Green also gives us Stone's perspective on drugs and their effects. Following his death 2015, a critic noted, in a snapshot retrospective view of Stone's career, that "even his experiments with drugs in the early sixties led Stone to understand that his view on life is going to remain religious no matter what."[12] And Stone himself confirmed this view, when he told the Washington Post in 1981:

| “ | But through his experimentation with drugs in the early 1960s, [Stone] has said, he confronted a deep religious sensibility. "I discovered that my way of seeing the world was always going to be religious — not intellectual or political — viewing everything as a mystic process."[13] | ” |

Works

Novels

- 1966: A Hall of Mirrors (novel)

- 1974: Dog Soldiers (novel) — winner of National Book Award[6]

- 1981: A Flag for Sunrise (novel) — finalist for Pulitizer prize; PEN/Faulkner Award finalist; twice a finalist for the National Book Award

- 1986: Children of Light (novel)

- 1992: Outerbridge Reach (novel) — finalist for the National Book Award

- 1998: Damascus Gate (novel) — finalist for the National Book Award

- 2003: Bay of Souls (novel)

- 2013: Death of the Black-Haired Girl (novel)

Short Stories

- 1997: Bear and His Daughter (short stories) — finalist for Pulitizer prize

- 2010: Fun with Problems (short stories)

Nonfiction

- 2007: Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties (memoir)

Screenplays

- 1970: WUSA (screenplay, based on A Hall of Mirrors)[25]

- 1978: Who'll Stop the Rain (screenplay, based on Dog Soldiers; co-author)[9]

References

- 1 2 "1982 Finalists". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- 1 2 "1998 Finalists". The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved 2013-09-18.

- 1 2 "Past Award Winners & Finalists". PEN/Faulkner: Award for Fiction. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- ↑ William James (May 30, 2010). "Robert Stone | Author". Big Think. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ↑ the five finalists: Dog Soldiers in 1975; A Flag for Sunrise was nominated twice for the NBA, in 1982 (hardcover) & 1983 (paperback); Outerbridge Reach in 1992; and Stone's final NBA finalist nomination was in 1998 for Damascus Gate

- 1 2 3 "National Book Awards – 1975". National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

(With essays by Jessica Hagedorn and others (five) from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) - ↑ http://www.fictionawardwinners.com/reviews.cfm?id=9

- ↑ "All Time 100 Novels". Time. October 16, 2005.

- 1 2 Who'll Stop the Rain at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Robert A. Stone – John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation". Gf.org. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ↑ http://www.penfaulkner.org/2015/01/28/episode-39-a-remembrance-of-robert-stone

- 1 2 "Robert Stone's Life and Death". ThePensters.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Robert Stone, Panelist - January 2006 Key West Literary Seminar". Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ Salon | The Salon Interview: Robert Stone, page 2

- ↑ "Robert Stone". Themodernnovel.org. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- 1 2 John McMurtrie, Chronicle Book Editor (2010-02-21). "Interview with Robert Stone". SFGate. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

- 1 2 3 Southhall, Ashley (January 10, 2015). "Robert Stone, Novelist Inspired by War, dies at 77". The New York Times. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ Counterculture Lion, Back in His Tidy Jungle, New York Times, January 5, 2007

- ↑ Stone, Robert: "Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties", pages 121–22. HarperCollins, 2007

- ↑ "Writers' Workshop - Robert Stone: Advanced Fiction - Key West Literary Seminar". Key West Literary Seminar. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ Lucie Weissová (10 January 2015). "Novelist Robert Stone, known for writing 'Dog Soldiers' and 'A Flag for Sunrise' dies at 77". US News. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- 1 2 Nancy Klingener. "Key West's Literary Community Mourns Robert Stone". wlrn.org. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ↑ Hillel Italie, The Associated Press. "Novelist Robert Stone, known for 'Dog Soldiers' dies at 77". Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ "A Hall of Mirrors. (Book, 1967)". [WorldCat.org]. 1999-02-22. Retrieved 2014-05-26.- Book published in 1967, but with copyright 1966; ie., "Publisher: Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1967 [1966]"

- 1 2 WUSA at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ The New York Public Library (August 21, 1937). "NYPL, Robert Stone Papers, c.1950–1992". Legacy.www.nypl.org. Retrieved 2011-08-14.

- ↑ Sam Allard. "Thomas Williams' 'The Hair of Harold Roux' deserves a rousing readership". cleveland.com. Retrieved 2011-07-30.

- ↑ "1982 National Book Awards Winners and Finalists, The National Book Foundation". Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ "1983 National Book Awards Winners and Finalists, The National Book Foundation". Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ "1992 National Book Awards Winners and Finalists, The National Book Foundation". Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ "1998 National Book Awards Winners and Finalists, The National Book Foundation". Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ↑ Alexandra Alter (8 November 2013). "Literary Giant Robert Stone Tries a Thriller". WSJ. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ Salikof, Ken (2013-09-06). "The Contemplating Stone: Robert Stone". Publishersweekly.com. Retrieved 2013-10-04.

External links

- Works by or about Robert Stone in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Robert Stone Papers at the NYPL

- William C. Woods (Winter 1985). "Robert Stone, The Art of Fiction No. 90". The Paris Review.

- "Robert Stone, Classic interview with the author of Damascus Gate", Identity Theory, April 20, 2009

- Interview with Robert Stone after publication of his memoir Prime Green LA Weekly, January 17, 2007

- "Antarctica, 1958" by Robert Stone, The New Yorker (June 12, 2006).

- "The Apostle of the Strung-Out" (Interview), Salon (April 14, 1997).

- "Kera Bolonik Talks to Robert Stone" (Interview) Bookforum (Summer 2003).

- Being There: An Interview with Robert Stone Rob Spillman interviewed Stone for issue #58 (Winter 2013) of Tin House. It was republished on-line as a tribute to Stone after his death.