Ryan's Daughter

| Ryan's Daughter | |

|---|---|

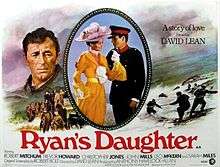

UK theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Lean |

| Produced by | Anthony Havelock-Allan |

| Written by | Robert Bolt |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

| Cinematography | Freddie Young |

| Edited by | Norman Savage |

Production company |

Faraway Productions |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release dates |

|

Running time |

195 minutes 206 minutes (DVD Version) |

| Country | Ireland (Dingle Peninsula) |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $13.3 million[1][2] |

| Box office |

$30,846,306 (domestic)[3] $14.6 million (rentals) |

Ryan's Daughter is a 1970 epic romantic drama film directed by David Lean.[4][5] The film, set in 1916, tells the story of a married Irish woman who has an affair with a British officer during World War I, despite moral and political opposition from her nationalist neighbours. The film is a very loose adaptation of Gustave Flaubert's novel Madame Bovary.

The film's stars are American and British: Robert Mitchum, Sarah Miles, John Mills, Christopher Jones, Trevor Howard and Leo McKern. The score was written by Maurice Jarre. It was photographed in Super Panavision 70 by Freddie Young. In its initial release, Ryan's Daughter was harshly received by critics[1] but was a box office success, grossing nearly $31 million[3] on a budget of $13.3 million, making the film the eighth highest-grossing picture of 1970. It received two Academy Awards, but was not nominated for best picture.

Plot

The daughter of the local publican, Tom Ryan (Leo McKern), Rosy Ryan (Sarah Miles) is bored with life in Kirrary, an isolated village on the Dingle Peninsula in County Kerry, Ireland. She falls in love with the local schoolmaster, Charles Shaughnessy (Robert Mitchum). She imagines, though he tries to convince her otherwise, that he will somehow add excitement to her life. The villagers are nationalists, taunting British soldiers from a nearby army base. Mr. Ryan publicly supports the recently suppressed Easter Rising, but secretly serves the British as an informer. Major Randolph Doryan (Christopher Jones) arrives to take command of the base. A veteran of World War I, he has been awarded a Victoria Cross, but has a crippled leg and suffers from shell shock.

Rosy is instantly and passionately attracted to Doryan, who suffers from intermittent flashbacks to the trenches of the First World War, also known as the Great War. He collapses. When he recovers, he is comforted by Rosy. The two passionately kiss until they are interrupted by the arrival of Ryan and the townspeople. The next day, the two meet in the forest for a passionate liaison. Charles becomes suspicious of Rosy, but keeps his thoughts to himself.

There is an intermission and an entr'acte.

Charles takes his students to the beach, where he notices Doryan's telltale footprints accompanied by a woman's in the sand. He tracks the prints to a cave and imagines Doryan and Rosy conducting an affair. Local halfwit Michael (John Mills) notices the footprints as well and searches the cave. He finds Doryan's Victoria Cross, which he pins on his own lapel. He proudly parades through town with the medal on his chest, but suffers abuse from the villagers. When Rosy comes riding through town, Michael approaches her tenderly. Between Rosy's feelings of guilt and Michael's pantomime, the villagers surmise that she is having an affair with Doryan.

One night, during a fierce storm, IRB leader Tim O'Leary (Barry Foster) – who had killed a police constable earlier – and a small band of his men arrive in Ryan's pub seeking help to recover a shipment of German arms smuggled by boat from the storm. When they leave, Ryan tips off the British. The entire town turns out to help the rebels. Ryan is the most outwardly devoted to the task, wading into the breakers to repeatedly salvage boxes of bullets and dynamite. O'Leary is overwhelmed by Ryan's devotion, and the town is ebullient. They gleefully free the rebels' truck from the wet sand, and follow it up the hill where Doryan and his troops lie in wait. O'Leary runs for his life. Doryan climbs atop the truck and wounds O'Leary with a rifle, but then he suffers a flashback and collapses. Rosy presses through the crowd in concern, outraging the villagers.

Charles tells Rosy that he had let her affair run its course, hoping that the infatuation would pass. He tells her that he will arrange for an amicable divorce. Rosy tells him the affair is over, but that night she returns to Doryan. In dismay, Charles wanders in his nightclothes to the beach, where local priest Father Collins (Trevor Howard) finds him. The villagers storm into the Shaughnessys' quarters at the schoolhouse and demand Rosy. They are convinced that she informed the British of the arms shipment. Ryan watches in shame and horror as his daughter takes the blame for his actions. The mob shears off her hair and strips off her clothes.

Doryan walks along the beach and gives his cigarette case to Michael. In gratitude, Michael leads Doryan to a cache of arms–-including dynamite–-that was not recovered. After Michael runs off, Doryan commits suicide by detonating the explosives. The next day, Rosy and Charles leave for Dublin, enduring the taunts of the villagers as they go.

Cast

- Sarah Miles as Rosy Ryan

- Robert Mitchum as Charles Shaughnessy

- Trevor Howard as Father Hugh Collins

- John Mills as Michael

- Christopher Jones as Major Randolph Doryan

- Leo McKern as Tom Ryan

- Barry Foster as Tim O'Leary

- Gerald Sim as Captain Smith

- Evin Crowley as Moureen Cassidy

- Marie Kean as Mrs. McCardle

- Arthur O'Sullivan as Joe McCardle

- Brian O'Higgins as Constable O'Connor

- Barry Jackson as a Corporal

Casting

Alec Guinness turned down the role of Father Collins; it had been written with him in mind, but Guinness, a Roman Catholic convert, objected to what he felt was an inaccurate portrayal of a Catholic priest. His conflicts with Lean while making Doctor Zhivago also contributed. Paul Scofield was Lean's first choice for the part of Shaughnessy, but he was unable to escape a theatre commitment. George C. Scott, Anthony Hopkins and Patrick McGoohan were considered but not approached, and Gregory Peck lobbied for the role but gave up after Robert Mitchum was approached.

The role of Major Doryan was written for Marlon Brando. Brando accepted, but problems with the production of Burn! forced him to drop out. Peter O'Toole, Richard Harris and Richard Burton were also considered. Lean then saw Christopher Jones in The Looking Glass War (1969) and decided he had to have Jones for the part, and so cast him without ever meeting him. He thought Chris had that rare Brando/Dean quality he wanted on film.

Production

Robert Bolt's original idea was to make a film of Madame Bovary, starring Miles. Lean read the script and said that he did not find it interesting, but suggested to Bolt that he would like to rework it into another setting. The film still retains parallels with Flaubert's novel – Rosy parallels Emma Bovary, Charles is her husband, Major Doryan is analogous to Rodolphe and Leon, Emma's lovers.

Lean had to wait a year before a suitably dramatic storm appeared. The image was kept clear of spray by a glass disk spinning in front of the lens.[6] Leo McKern was injured and badly shaken while filming the storm sequence, nearly drowning and losing his glass eye. He also disliked the amount of time spent working on the project. His comment on the experience was, "I don't like to be paid £500 a week for sitting down and playing Scrabble."

Reportedly, Mitchum was initially reluctant to take the role. While he admired the script, he was undergoing a personal crisis at the time and when pressed by Lean as to why he wouldn't be available for filming, told him "I was actually planning on committing suicide." Upon hearing of this, scriptwriter Bolt told him, "Well, if you just finish working on this wretched little film and then do yourself in, I'd be happy to stand the expenses of your burial."

Mitchum clashed with Lean, saying that "[W]orking with David Lean is like constructing the Taj Mahal out of toothpicks"; despite this, Mitchum confided to friends and family that he felt Ryan's Daughter was among his best roles and he regretted the negative response the film received. In a radio interview, Mitchum claimed (despite the difficult production) Lean was one of the best directors he'd worked with.[7]

Christopher Jones claimed to have had an affair with Sharon Tate, who was killed by Charles Manson and his followers during filming, which devastated Jones. Sarah Miles and Jones also grew to dislike one another, leading to trouble when filming the love scenes. Christopher was engaged to Olivia Hussey, and he was not attracted to Miles. He even refused to do the forest love scene with her, which prompted Miles to conspire with Mitchum. It was Mitchum who settled on the idea of drugging Jones by sprinkling an unspecified substance on his cereal. Mitchum overdosed Jones, however, and the actor was nearly catatonic during the love scene.[8] Christopher Jones was never told by the producers about the drugging and believed he was having a nervous breakdown .

Jones and Lean clashed frequently. Lean also found that Jones' voice was too flat to be compelling, and he felt compelled to overdub all of his lines by Julian Holloway. Lean was not alone in his disappointment with Jones. His retirement from acting was purportedly due to the bad reviews he received for Ryan's Daughter.[9]

Ryan's Daughter was the last feature film photographed entirely in the 65mm Super Panavision format until Far and Away (1992), which was shot largely at the same locations. Owing to bad weather, many of the beach scenes were actually filmed in Cape Town, South Africa.

The village in the film was built by the production company from stone so that it could withstand the storms. Villagers from the town of Dunquin were hired as extras. The area was at the time economically destitute, but the amount of money spent in the town — nearly a million pounds — revived the local economy and led to increased immigration to the Dingle Peninsula. Disputes over land meant the entire village was razed after filming. The schoolhouse still exists, but in a ruined state. In the scene before Doryan commits suicide, there is a cut from a sunset to Charles striking a match, which is a sly allusion to Lawrence of Arabia with its famous cut from Peter O'Toole blowing out a match to a sunrise in the desert.

MPAA ratings

The MPAA originally gave Ryan's Daughter an "R" rating. A nude scene between Miles and Jones, as well as its themes involving infidelity, were the primary reasons for the MPAA's decision.[10] At the time, MGM was having financial trouble and appealed the rating not due to artistic but financial reasons.

At the appeal hearing, MGM executives explained that they needed the less restrictive rating to allow more audience into the theatres; otherwise the company would not be able to survive financially. The appeal was overturned and the film received a "GP" rating, which later became "PG". Jack Valenti considered this to be one of the tarnishing marks on the rating system.[11] When MGM resubmitted the film to the MPAA in 1996, it was re-rated "R."[12]

The film is rated M in Australia and M in New Zealand; it was originally rated PG in Australia and PG in New Zealand.

Reception

Upon its initial release, the film received a hostile reception from many film reviewers. Roger Ebert felt that "Lean's characters, well written and well acted, are finally dwarfed by his excessive scale."[13] According to James Wolcott, at a gathering of the National Society of Film Critics, Time critic Richard Schickel asked Lean "how someone who made Brief Encounter could make a piece of bullshit like Ryan's Daughter."[14]

Some attribute the negative reviews to critics' expectations being too high, following the three epics Lean had directed in a row before Ryan's Daughter. The preview cut, which ran to over 220 minutes, was criticised for its length and poor pacing; Lean felt obliged to remove up to 17 minutes of footage before the film's wide release. The missing footage has not been restored or located. Lean took these criticisms very personally, claiming at the time that he would never make another film. (Others dispute this, citing the fact that Lean tried but was unable to get several projects off the ground, including The Bounty.) The film was moderately successful worldwide at the box office and was one of the most successful films of 1970 in Britain, where it ran at a West End theatre for almost two years straight.

The film was also criticised for its perceived depiction of the Irish proletariat as uncivilised. An Irish commentator in 2008 called them "the local herd-like and libidinous populace who lack gainful employment to keep them occupied".[15] Some criticised the film as an attempt to blacken the legacy of the 1916 Easter Rising and the subsequent Irish War of Independence in relation to the eruption of "the Troubles" in Northern Ireland around the time of the film's release. Since the film's release on DVD, Ryan's Daughter has been reconsidered by some critics; it has been called an overlooked masterpiece, countering many of the criticisms such as its alleged "excessive scale". Other elements, like John Mills' caricature of 'the village idiot' (an Oscar-winning performance), have been met with ambivalence.[16]

Awards and honors

Academy Awards

Wins:

- Best Actor in a Supporting Role – John Mills

- Best Cinematography – Freddie Young

Nominations:[17]

- Best Actress in a Leading Role – Sarah Miles

- Best Sound – Gordon McCallum, John Bramall

Others

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores – Nominated[18]

References

- 1 2 Hall, S. and Neale, S. Epics, spectacles, and blockbusters: a Hollywood history (p. 181). Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan; 2010; ISBN 978-0-8143-3008-1. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ↑ MGM Posts Profit of , Milion, Best Gain in 25 Years: MGM PROFIT Delugach, Al. Los Angeles Times (1923–Current File) [Los Angeles, Calif] 3 November 1971: e11.

- 1 2 "Ryan's Daughter, Box Office Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ↑ Variety film review; 11 November 1970, p. 15.

- ↑ The Irish Filmography 1896–1996; Red Mountain Press; 1996. p. 180.

- ↑ Shooting the storm sequence through a Clearview screen http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51M9EPHPPWL._SS500_.jpg

- ↑ Sound on Film Interview Series: Ryan's Daughter

- ↑ Phillips, Gene. Beyond the Epic: The Life and Films of David Lean. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006. 381.

- ↑ Phillips, Gene. Beyond the Epic: The Life and Films of David Lean. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2006. 386.

- ↑ Life Magazine, 20 August 1971.

- ↑ The Dame in the Kimono, Jerold L. Simmons and Leonard L. Jeff, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1990.

- ↑

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (20 December 1970). "Ryan's Daughter". rogerebert.suntimes.com.

- ↑ Wolcott, James (April 1997). "Waiting for Godard". Vanity Fair. Conde Nast.

- ↑ Brereton, Dr. P., RELIGION AND IRISH CINEMA: A CASE STUDY, Irish Quarterly Review, Autumn 2008, pp. 321–32.

- ↑ McFarlane, Brian. "Mills, Sir John (1908–2005)".

- ↑ "The 43rd Academy Awards (1971) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 27 August 2011.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 19 August 2016.

External links

- Ryan's Daughter at the Internet Movie Database

- British Film Institute on Ryan's Daughter

- Location on The Dingle Peninsula

Further reading

- Michael Tanner (2012). Troubled Epic – On Location with Ryan's Daughter. Cork: The Collins Press. ISBN 978-1-84889-1456.

- Constantine Santas (2011). The Epic Films of David Lean. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8210-2.