Space Shuttle Challenger

| Challenger OV-099 | |

|---|---|

|

Challenger is launched on its first mission, STS-6 | |

| OV designation | OV-099 |

| Country | United States |

| Contract award | January 1, 1979 |

| Named after | HMS Challenger (1858) |

| Status | Destroyed January 28, 1986 |

| First flight |

STS-6 April 4–9, 1983 |

| Last flight |

STS-51-L January 28, 1986 |

| Number of missions | 10 |

| Time spent in space | 62 days 07:56:22[1] |

| Number of orbits | 995 |

| Distance travelled | 25,803,939 mi (41,527,414 km) |

| Satellites deployed | 10 |

Space Shuttle Challenger (Orbiter Vehicle Designation: OV-099) was the second orbiter of NASA's space shuttle program to be put into service following Columbia. The shuttle was built by Rockwell International's Space Transportation Systems Division in Downey, California. Its maiden flight, STS-6, started on April 4, 1983. It launched and landed nine times before breaking apart 73 seconds into its tenth mission, STS-51-L, on January 28, 1986, resulting in the death of all seven crew members, including a civilian school teacher. It was the first of two shuttles to be destroyed in flight, the other being Columbia in 2003. The accident led to a two-and-a-half year grounding of the shuttle fleet; flights resumed in 1988 with STS-26 flown by Discovery. Challenger itself was replaced by Endeavour which was built using structural spares ordered by NASA as part of the construction contracts for Discovery and Atlantis.

History

Challenger was named after HMS Challenger, a British corvette that was the command ship for the Challenger Expedition, a pioneering global marine research expedition undertaken from 1872 through 1876.[2] The Apollo 17 lunar module that landed on the Moon in 1972 was also named Challenger.[2]

Construction

Because of the low production volume of orbiters, the Space Shuttle program decided to build a vehicle as a Structural Test Article, STA-099, that could later be converted to a flight vehicle. The contract for STA-099 was awarded to North American Rockwell on July 26, 1972, and its construction was completed in February 1978.[3] After STA-099's rollout, it was sent to a Lockheed test site in Palmdale, where it spent over 11 months in vibration tests designed to simulate entire shuttle flights, from launch to landing.[4] In order to prevent damage during structural testing, qualification tests were performed to a factor of safety of 1.2 times the design limit loads. The qualification tests were used to validate computational models, and compliance with the required 1.4 factor of safety was shown by analysis.[5] STA-099 was essentially a complete airframe of a Space Shuttle orbiter, with only a mockup crew module installed and thermal insulation placed on its forward fuselage.[6]

NASA planned to refit the prototype orbiter Enterprise (OV-101), used for flight testing, as the second operational orbiter, but Enterprise lacked most of the systems needed for flight, including a functional propulsion system, thermal insulation, a life support system, or most of the cockpit instrumentation. Modifying her for flight article status would have been far too difficult, expensive, and time-consuming. Since STA-099 was not as far along in the construction of its airframe, it would be easier to upgrade to a flight article. Because STA-099's qualification testing prevented damage, NASA found that rebuilding STA-099 as OV-099 would be less expensive than refitting Enterprise. Work on converting STA-099 into Challenger began in January 1979, starting with just the crew module (the pressurized portion of the vehicle) as the rest of the orbiter was still used by Lockheed. STA-099 returned to the Rockwell plant in November 1979, and the original unfinished crew module was replaced with the newly constructed model. Major portions of STA-099, including the payload bay doors, body flap, wings and vertical stabilizer, also had to be returned to their individual subcontractors for rework. By early 1981, most of these components had returned to Palmdale and were reinstalled on the orbiter. Work continued on the conversion until July 1982.[4]

Challenger (and the orbiters built after it) had fewer tiles in its Thermal Protection System than Columbia, though it still made heavy use of the white LRSI tiles on the cabin and main fuselage compared to the later orbiters. Most of the tiles on the payload bay doors, upper wing surfaces, and rear fuselage surfaces were replaced with DuPont white Nomex felt insulation. These modifications as well as an overall lighter structure allowed Challenger to carry 2,500 lb (1,100 kg) more payload than Columbia. Challenger's fuselage and wings were also stronger than Columbia's despite being lighter.[4] The hatch and vertical stabilizer tile patterns were also different from that of the other orbiters. Challenger was also the first orbiter to have a head-up display system for use in the descent phase of a mission, and the first to feature Phase I main engines rated for 104% maximum thrust.

Construction milestones (as STA-099)

| Date | Milestone[7] |

|---|---|

| 1972 July 26 | Contract Award to North American Rockwell |

| 1975 November 21 | Start structural assembly of crew module |

| 1976 June 14 | Start structural assembly of aft fuselage. |

| 1977 March 16 | Wings arrive at Palmdale from Grumman |

| 1977 September 30 | Start of Final Assembly |

| 1978 February 10 | Completed Final Assembly |

| 1978 February 14 | Rollout from Palmdale |

Construction milestones (as OV-099)

| Date | Milestone[7] |

|---|---|

| 1979 January 5 | Contract Award to Rockwell International, Space Transportation Systems Division |

| 1979 January 28 | Start structural assembly of crew module |

| 1980 November 3 | Start of Final Assembly |

| 1981 October 23 | Completed Final Assembly |

| 1982 June 30 | Rollout from Palmdale |

| 1982 July 1 | Overland transport from Palmdale to Edwards |

| 1982 July 5 | Delivery to KSC |

| 1982 December 19 | Flight Readiness Firing (FRF) |

| 1983 April 4 | First Flight (STS-6) |

Flights and modifications

After its first flight in April 1983, Challenger quickly became the workhorse of NASA's Space Shuttle fleet, flying far more missions per year than Columbia. In 1983 and 1984, Challenger flew on 85% of all Space Shuttle missions. Even when the orbiters Discovery and Atlantis joined the fleet, Challenger flew three missions a year from 1983 to 1985. Challenger, along with Discovery, was modified at Kennedy Space Center to be able to carry the Centaur-G upper stage in its payload bay. If flight STS-51-L had been successful, Challenger's next mission would have been the deployment of the Ulysses probe with the Centaur to study the polar regions of the Sun.

Challenger flew the first American woman, African-American, Dutchman and Canadian into space; three Spacelab missions; and performed the first night launch and night landing of a Space Shuttle. Challenger was also the first space shuttle to be destroyed in an accident during a mission. The collected debris of the vessel is currently buried in decommissioned missile silos at Launch Complex 31, Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. A section of the fuselage recovered from Space Shuttle Challenger can also be found at the “Forever Remembered” memorial at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida. From time to time, further pieces of debris from the orbiter wash up on the Florida coast.[8] When this happens, they are collected and transported to the silos for storage. Because of its early loss, Challenger was the only space shuttle that never wore the NASA "meatball" logo, and was never modified with the MEDS "glass cockpit". The tail was never fitted with a drag chute – it was fitted to the remaining orbiters in 1992. Also because of its early demise Challenger was also one of only two shuttles that never visited the Mir Space Station or the International Space Station - the other one being its sister ship Columbia.

|

|

| Challenger's rollout from Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) to the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB). Photo 1983-8-25 courtesy of NASA. |

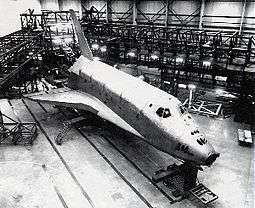

Challenger while in service as structural test article STA-099. |

| # | Date | Designation | Launch pad | Landing location | Notes | Mission duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | April 4, 1983 | STS-6 | LC-39A | Edwards Air Force Base | Deployed TDRS-A. First spacewalk during a space shuttle mission. |

5 days, 00 hours, 23 minutes, 42 seconds |

| 2 | June 18, 1983 | STS-7 | LC-39A | Edwards Air Force Base | Sally Ride becomes first American woman in space. Deployed two communications satellites. |

6 days, 02 hours, 23 minutes, 59 seconds |

| 3 | August 30, 1983 | STS-8 | LC-39A | Edwards Air Force Base | Guion Bluford becomes first African-American in space First shuttle night launch and night landing. |

6 days, 01 hours, 08 minutes, 43 seconds |

| 4 | February 3, 1984 | STS-41-B | LC-39A | Kennedy Space Center | First untethered spacewalk using the Manned Maneuvering Unit. Deployed WESTAR and Palapa B-2 communications satellites unsuccessfully (both were retrieved during STS-51-A). |

7 days, 23 hours, 15 minutes, 55 seconds |

| 5 | April 6, 1984 | STS-41-C | LC-39A | Edwards Air Force Base | Solar Maximum Mission service mission. | 6 days, 23 hours, 40 minutes, 07 seconds |

| 6 | October 5, 1984 | STS-41-G | LC-39A | Kennedy Space Center | First mission to carry two women. Marc Garneau becomes first Canadian in space. |

8 days, 05 hours, 23 minutes, 33 seconds |

| 7 | April 29, 1985 | STS-51-B | LC-39A | Edwards Air Force Base | Carried Spacelab-3. | 7 days, 00 hours, 08 minutes, 46 seconds |

| 8 | July 29, 1985 | STS-51-F | LC-39A | Edwards Air Force Base | Carried Spacelab-2. Only STS mission to abort after launch. |

7 days, 22 hours, 45 minutes, 26 seconds |

| 9 | October 30, 1985 | STS-61-A | LC-39A | Edwards Air Force Base | Carried German Spacelab D-1.

Wubbo Ockels becomes the first Dutchman in space |

7 days, 00 hours, 44 minutes, 51 seconds |

| 10 | January 28, 1986 | STS-51-L | LC-39B | (planned to land at Kennedy Space Center). | Shuttle disintegrated after launch, killing all seven astronauts on board. Would have deployed TDRS-B. | 0 days, 00 hours, 01 minute, 13 seconds |

Mission insignias

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

See also

- List of human spaceflights

- List of Space Shuttle crews

- List of Space Shuttle missions

- Timeline of Space Shuttle missions

- List of human spaceflights chronologically

- Challenger flag

- Challenger Colles, a mountain range on Pluto named for the space shuttle

References

- ↑ Harwood, William (October 12, 2009). "STS-129/ISS-ULF3 Quick-Look Data" (PDF). CBS News. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- 1 2 "Orbiter Vehicles", Kennedy Space Center, NASA, 2000-10-03, retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ↑ "NASA - Space Shuttle Overview: Challenger (OV-099)". Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Lardas, Mark (2012). Space Shuttle Launch System: 1972-2004. Osprey Publishing. p. 36.

- ↑ NASA Engineering and Safety Center (2007). Design Development Test and Evaluation (DDT&E) Considerations for Safe and Reliable Human Rated Spacecraft Systems, Vol. II, June 14, 2007, p. 23.

- ↑ Evans, Ben (2007). Space Shuttle Challenger: Ten Journeys Into the Unknown. Praxis Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 0-387-46355-0.

- 1 2 "Shuttle Orbiter Challenger (OV-099)". NASA/KSC. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ↑ CNN (1996). "Shuttle Challenger debris washes up on shore". CNN. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ↑ Stamps (Philately)/Space Shuttle Challenger

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Further reading

- Evans, Ben (2007). Space shuttle challenger: ten journeys into the unknown. Published in association with Praxis Pub. ISBN 978-0-387-46355-1

- Harris, Hugh (2014). Challenger: An American Tragedy: The Inside Story from Launch Control. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781480413504

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Space Shuttle Challenger. |

- Mission Summary Archive

- Ronald Reagan: Address to the Nation on the Explosion of the Space Shuttle Challenger

- Space Shuttle Challenger Explosion video

- Shuttle Orbiter Challenger (OV-99)

- Rogers Commission Report

- Astronautix on Challenger

- Space Shuttle Challenger: A Tribute – slideshow by Life (magazine)

- Go or No Go: The Challenger Legacy an Emmy-winning short documentary by Retro Report

- Challenger Mission Videos of the Accident from Spaceflightnow.com

- NASA film on the accident and investigation downloadable from archive.org The Internet Archive

- Memorial to Greg Jarvis in Hermosa Beach, California at "Sites of Memory"

- Personal Observations on the Reliability of the Shuttle by R. P. Feynman

- RealPlayer video of Feynman's O-Ring demonstration (low quality)

- CBS Radio news Bulletin Anchored by Christopher Glenn of the Challenger Disaster from January 28, 1986, Part 2 of CBS Radio coverage of Challenger Disaster, Part 3 of CBS Radio News coverage of Challenger disaster, Part 4 of CBS Radio news coverage of Challenger disaster

- Image of silo storing Challenger debris

- Space Shuttle Memorial covering both space shuttle disasters

- Space Shuttle Challenger STS-51L Accident Investigation