South Carolina gubernatorial election, 1876

The 1876 South Carolina gubernatorial election was held on November 7, 1876 to select the governor of the state of South Carolina. The election campaign was a referendum on the Radical Republican-led state government and their Reconstruction policies. Opponents disputed the challenger Wade Hampton III's victory, gained by a margin of little more than 1100 votes statewide. But he took office in April 1877, after President Hayes withdrew federal troops as a result of a national Democratic compromise, and the incumbent Daniel Henry Chamberlain left the state.

Governor Chamberlain had been unable to preserve the peace in the months beforehand, reducing support for Republicans as white Democratic paramilitary groups attacked Republican blacks in numerous areas of the state, particularly the Piedmont, in violent incidents including the Hamburg Massacre, and riots at Ellenton and Cainhoy. Under this pressure, some blacks were discouraged from voting altogether; others had aligned with Democrats for a variety of reasons. White voters overwhelmingly supported the Democratic ticket in November. The turbulent atmosphere ended before election day, which was peaceful.

Democrat Wade Hampton narrowly won with slightly more than 1100 votes statewide following the suppression of black voters, particularly in Edgefield County. The election was disputed and a prolonged contest ensued as both parties established separate governments. Chamberlain lost most of his support and in early 1877 was kept in office by Federal troops guarding the state capitol. When President Rutherford B. Hayes ordered the troops to stand down, Chamberlain left the state and Hampton was confirmed as the 77th governor of South Carolina.

Background

South Carolina entered 1876 having had eight years of Radical Republican rule. Whites had resisted social and political changes after the war, and believed that the Reconstruction programs set up by the Republicans were used by corrupt politicians and carpetbaggers to their financial benefit. At the same time, many whites were angered by the passage of 13th, 14th, 15th amendments which guaranteed citizenship rights to former slaves. Former Confederates were not allowed to vote or hold office for several years until the passage of the Amnesty Act in 1872. Following that, Southern Democrats ran for office and sought to regain political control of the state. The elections were seasons of violence by white paramilitary groups against blacks to disrupt Republican meetings and reduce their vote. There were some divisions among freedmen and blacks who had been free before the war; many black citizens of the state began to question the efficacy of Republican rule and some former slaves later stated that life was better under slavery.[1]

But, most blacks remained steadfastly loyal to the Republican Party because of the brutality of Southern whites. After the end of the Civil War, many whites had conducted a decade-long insurgency to maintain white supremacy and suppress black political power. Black citizens, however, constituted a sizable majority of the electorate, particularly in the Low Country and with narrow majorities in several Piedmont counties. The state Democratic Party was unorganized, not having contested a state election since 1868, when it was utterly defeated by the Republicans.

The Democratic Party also divided on a strategy for contesting the general election. Most Democrats heading into the May convention decided to not oppose the governorship and other state offices because Governor Daniel Henry Chamberlain had implemented many favorable reforms. Known as fusionists, they also felt that any effort spent on state offices would be wasted and better served by trying to acquire a majority in the General Assembly.

The more ardent Democrats, called the "Straightout Democrats", gained strength after the General Assembly elected former Governor Franklin J. Moses Jr. and William Whipper to circuit judgeships, as they were considered corrupt. The nominations were blocked by Governor Chamberlain, but the Straightouts believed that meaningful political reform would happen only when Democrats gained power. In their opinion, every race from governor to coroner had to be contested.

Democratic conventions

May convention

A reinvigorated South Carolina Democratic Party convened in Columbia from May 4 to May 5. Its purpose was to select 14 delegates and alternates to the National Democratic Convention in St. Louis and state the policies of the party. However, the party remained divided between the Fusionists and the Straighouts as to whether run a state ticket or not.

The debate continued through the summer between the two as to which approach would be best for the Democratic Party. The Hamburg Massacre in July, although limited in fatalities compared to the total from later incidents at Ellenton, Charleston and Cainhoy, persuaded many whites that Governor Chamberlain's administration was unable to maintain order. In most of these events, blacks were killed in much greater number than whites, particularly at Ellenton. Populist Democrats ended hopes of supporting fusion with the Republicans, and the Straighouts became the dominant force within the Democratic Party.

August convention

The Democrats reconvened in Columbia for the nominating convention held on August 15 through August 17. Since the Republicans had yet to meet, the candidacy of Governor Chamberlain was uncertain, which also undermined the Fusionists. Straightouts had been rallied by the assertion of white supremacy by white paramilitary groups of Red Shirts, who killed seven blacks in Hamburg, five of them murdered outright while held as prisoner by whites. One white died in the confrontation. The first test of Straightout strength in the Democratic Party was the election of the President of the Convention. By a vote of 80 to 66, the Straightout candidate was elected and after a secret session, the nomination process began.

Matthew Butler nominated Wade Hampton for the post of governor and the delegates unanimously approved the nomination by acclamation. Wade Hampton, although a supporter of the Straightouts, had a moderate reputation that enabled him to unite the two factions of the party and attract some black voters. The Democrats recruited blacks to the Red Shirts paramilitary groups and presented them prominently in public parade.[2]

The Democratic platform that emerged from the convention was vague and noncommittal to specifics. Pledges were made to restore order, reform the government, and lower taxes; but no specific policies were formulated. The Straightouts knew that only a consensus of general ideas would unite the party and enable election of Democrats to statewide offices.

Republican conventions

A group of prominent South Carolina Republicans, notably Senator John J. Patterson and Robert B. Elliott, organized an opposition to Governor Chamberlain prior to the state convention. The group was upset by the reforms enacted by the Governor, especially the removal of corrupt Republicans from positions and replacing them with Democrats. The goal was to weaken Governor Chamberlain enough so that he would be removed from the ticket in November or forced to make favorable concessions.

April convention

The Republicans gathered in Columbia from April 12 to April 14 for the state convention to nominate 14 delegates to the National Republican Convention in Cincinnati. Those in opposition of Governor Chamberlain first succeeded in winning control of the temporary chairmanship for the convention when their candidate defeated the Governor by a vote of 80 to 40.

Having achieved effective control of the convention, the opposition to Governor Chamberlain proceeded to select delegates to the national convention with the purpose of excluding the governor from the delegation. However, the convention descended into chaos between those in support of the governor and those in opposition. An inkstand was thrown at the head of a delegate and a chair was raised above Governor Chamberlain with the intention of striking him.[3]

Governor Chamberlain responded with a powerful diatribe of those opposing him by accusing them of siding with the Ku Klux Klan. He then reaffirmed his loyalty to the Republican Party and its platform and explained that his actions in office were meant to serve the Party. Most delegates were convinced of the Governor's sincerity, and he was elected as a delegate-at-large to the national convention by a vote of 89 to 32.

September convention

| Republican nomination for Governor | ||

|---|---|---|

| Candidate | Votes | % |

| Daniel Henry Chamberlain | 88 | 71.6 |

| Thomas C. Dunn | 32 | 26.0 |

| D.T. Corbin | 2 | 1.6 |

| Robert B. Elliott | 1 | 0.8 |

Worried by his support among Republicans, Governor Chamberlain canvassed several counties of the state. Accompanied by Republicans held in low esteem by the white community, the meetings were often disrupted by Democrats. However, the growing strength and militancy of the Democrats served the purpose of reducing the opposition to Chamberlain within the Republican Party.

When the Republicans met for the nominating convention in Columbia on September 13 through September 15, Governor Chamberlain was renominated with little difficulty. However, those opposed to Chamberlain sought to compensate for their defeat by adding themselves to the ticket. Robert B. Elliott became the nominee for attorney general and Thomas C. Dunn the nominee for comptroller general.

Both had been very vocal in their opposition to Chamberlain and Elliott was notorious for corruption and his belief of black supremacy. After the election, Chamberlain regretted the inclusion of Elliott on the ticket and thought that Elliott's removal should have been the condition for his acceptance as nominee for governor.[4]

The platform adopted by the Republicans contained many specific and innovative proposals that were to be effected either as amendments to the state constitution or through legislative action:

- Ban government funds from being given to religious organizations.

- A permanent tax to support public schools.

- Tort reform.

- Repeal of the agriculture lien law.

- Use of convict labor.

- Require cattle owners to fence their land.

The results of the convention for the Republicans were mixed; on one hand, the party emerged united from their convention for the first time since 1868, but it came with a heavy price as the more moderate black and white members of the party switched to support Hampton and the Democrats.

General election

Democratic campaign

The Democratic strategy for the election was twofold; Wade Hampton was to attract moderate voters by appearing as a senior statesman. His chief lieutenant, Martin Gary, was to implement the Mississippi Plan in South Carolina. Known as the Shotgun Policy in South Carolina, the Mississippi Plan called for the bribery or intimidation of black voters. Financial enticements were given to blacks who supported the Democrats, and violence was waged on others in order to convince them to join a Democratic club for protection.

The first step of the Democratic campaign was to set up clubs to organize its members; the more militant Democrats were organized into the rifle clubs whereas the red shirt clubs were arranged to appeal to black voters. By election day, the Democrats had enrolled almost every white man not associated with the Republican party into a club and set up several clubs for blacks.

Supporters of the Democratic Party often wore red shirts in response to Oliver Morton's use of the bloody shirt to maintain support in the North for Reconstruction of the South.[5] They would often parade through towns on horseback such as to give an impression of greater numbers and shouted "Hurrah for Hampton" as their slogan. These demonstrations served several purposes for the Democrats: they brought together whites, frightened Republicans and inspired blacks towards their cause.

Another important aspect of the Mississippi Plan put into effect was the disruption of Republican meetings and the demanding of equal time. The campaign device was called "dividing time" and it proved to be one of the more useful techniques employed by the Democrats in the campaign for three reasons: the strong show of force intimidated the black voters; it terrified Republican candidates and disgraced them in front of the blacks; and because most black voters were illiterate, it was the only possible way for the Democrats to reach them with their arguments since the newspapers were useless as they could not be read. The harassment of the Republicans had gotten so bad that the state Democratic committee had to warn its members that the purpose was to attract black voters and not to terrorize them.[6]

An unofficial policy employed by the whites, yet equally effective as the others, was "preference, not proscription." Basically, blacks who espoused support for the Democrats were given a certificate that allowed for them to have priority in employment and trade. The device was not used on the farms because the contracts lasted until January, but it instead wreaked havoc among the black artisans in the urban areas. The state Democratic committee never endorsed the tactic, and Hampton urged its ending after the end of the campaign.[7]

Poole argues that in waging its campaign Democrats portrayed the Lost Cause scenario through "Hampton Days" celebrations shouting "Hampton or Hell!". They staged the contest between Hampton and governor Chamberlain as a religious struggle between good and evil, and calling for "redemption."[8] Indeed, throughout the South the conservatives who overthrew Reconstruction were often called "Redeemers", echoing Christian theology.[9]

Democratic black vote

Democrats recognized the black majority in the state and realized that the only way for them to win the election was through the addition of black voters to its ranks. This was a tricky problem for the party because they were known for upholding slavery and introducing the black codes. However, the Republicans had become notoriously corrupt and little progress was made towards the promises made to blacks, such as 40 acres and a mule. Furthermore, it angered many blacks that a former slave trader, Joe Crews, was elected as a Republican to the General Assembly.[10]

Those blacks enticed to join and vote for the Democratic Party were attracted to the paternalistic, moderate appeal of Wade Hampton.[11] They resented the northern politicians who had come to rule the state and saw Hampton as someone who would redeem the state out of its current despair. But, black Democrats often faced ostracism from the black community and their own threats of violence. The black women were especially noted for their cruelty; they would strip known black Democrats naked in public and some of the wives would leave their husbands or refuse to sleep with them. The daughter of a black Democrat was whipped at school for her father's support of Hampton.[12]

Republican campaign

The entirety of the Republican campaign for the general election in November was based on maintaining the black vote. There was little campaigning by Republican candidates and one of Governor Chamberlain's newspapers, Columbia Daily Union-Herald, noted that "Public meetings are not necessary to arouse the Republicans, nor to inform them. On the day of election nine-tenths of them could be directed to cast their ballots at one poll, if necessary."[13]

The Republicans made a point of making a show of force with its black members and to impress upon other black voters that a vote for the Democrats would result in more of the violence they had already suffered.

Election results

The general election was held on November 7, 1876, and there were few instances of disturbance. At each polling place, there were federal supervisors from both the Democratic and Republican parties. Federal troops were also stationed at the county seats to preserve the peace at the polling places if needed, but they were never called upon.

As the results were coming in on Wednesday morning, it appeared that Chamberlain would win, but Hampton had taken a very narrow lead by Thursday. Hampton claimed victory with slightly more than an 1100-vote margin statewide. Chamberlain and the Republicans disputed the victory, based on widespread fraud and intimidation by Democrats. In Aiken County, where the Hamburg Massacre had occurred, Republican votes dropped to less than 100, but "Democratic votes quadrupled."[14] The total vote in Edgefield exceeded the total voting age population by more than 2,000 and Republican votes were suppressed.[14] In Laurens County, the votes also exceeded the total number of registered voters.[15]

When the Republican-dominated Board of State Canvassars met after the election to certify the results, they did not certify the election results from Edgefield and Laurens counties. They were ordered by the state supreme court to certify all the results. But, effectively, the results from those counties were thrown out. The state supreme court held the board members in contempt of court and placed them in the Richland County jail. A federal judge annulled the order of the state supreme court and issued a writ of habeas corpus in favor of the board members.

In the morning of November 28, prior to the convening of the General Assembly, Chamberlain ordered two companies of federal troops under the command of General Thomas H. Ruger to the State House. This action was approved by President Ulysses S. Grant on November 26 in order to prevent a violent takeover by the Democrats and to block admission by Democratic members from the disputed Edgefield and Laurens counties.

The Democrats left the General Assembly en masse to set up a rival legislature at Carolina Hall, complete with representatives who had been excluded by the Republicans. In control of the government and backed by the support of federal troops, the Republicans discarded the election returns from Edgefield and Laurens counties for the gubernatorial race and declared Chamberlain elected for a second term on December 5.

| Republican count for the South Carolina Gubernatorial Election, 1876 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % |

| Republican | Daniel Henry Chamberlain | 86,216 | 50.9 |

| Democratic | Wade Hampton III | 83,071 | 49.1 |

The Democrats derided the installation of Chamberlain as governor by the Republicans and on December 14, they declared Hampton Governor of South Carolina. They included returns from Edgefield and Laurens counties in their tally, which meant out of 184,943 registered voters in 1875, only 555 voters did not cast a ballot in the election. The results as declared by the Democrats held up to be the official results of the election when Hampton became the sole governor on April 11, 1877.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ± | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Wade Hampton III | 92,261 | 50.3 | +50.3 | |

| Republican | Daniel Henry Chamberlain | 91,127 | 49.7 | -4.2 | |

| Majority | 1,134 | 0.6 | -7.2 | ||

| Turnout | 183,388 | 99.2 | |||

| Democratic gain from Republican | |||||

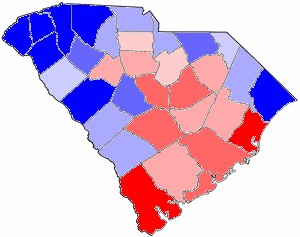

County results

| County | Hampton | Chamberlain | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |

| Abbeville | 3,852 | 51.2 | 3,669 | 48.8 |

| Aiken | 3,221 | 56.4 | 2,495 | 43.6 |

| Anderson | 4,155 | 78.7 | 1,124 | 21.3 |

| Barnwell | 3,956 | 58.7 | 2,778 | 41.3 |

| Beaufort | 2,274 | 23.0 | 7,604 | 77.0 |

| Charleston | 8,809 | 36.9 | 15,032 | 63.1 |

| Chester | 2,005 | 45.5 | 2,404 | 54.5 |

| Chesterfield | 1,631 | 62.3 | 985 | 37.7 |

| Clarendon | 1,436 | 43.3 | 1,881 | 56.7 |

| Colleton | 2,984 | 41.8 | 4,163 | 58.2 |

| Darlington | 2,752 | 44.0 | 3,507 | 56.0 |

| Edgefield | 6,267 | 66.9 | 3,107 | 33.1 |

| Fairfield | 2,159 | 43.3 | 2,832 | 56.7 |

| Georgetown | 1,058 | 27.5 | 2,787 | 72.5 |

| Greenville | 4,172 | 70.7 | 1,729 | 29.3 |

| Horry | 1,939 | 76.7 | 588 | 23.3 |

| Kershaw | 1,757 | 46.0 | 2,063 | 54.0 |

| Lancaster | 1,541 | 55.5 | 1,236 | 44.5 |

| Laurens | 2,916 | 61.8 | 1,804 | 38.2 |

| Lexington | 2,129 | 62.9 | 1,256 | 37.1 |

| Marion | 3,149 | 55.8 | 2,492 | 44.2 |

| Marlboro | 1,945 | 54.7 | 1,608 | 45.3 |

| Newberry | 2,196 | 44.3 | 2,761 | 55.7 |

| Oconee | 2,083 | 79.9 | 524 | 20.1 |

| Orangeburg | 2,870 | 39.1 | 4,469 | 60.9 |

| Pickens | 2,002 | 83.1 | 406 | 16.9 |

| Richland | 2,435 | 38.7 | 3,857 | 61.3 |

| Spartanburg | 4,677 | 76.1 | 1,467 | 23.9 |

| Sumter | 2,382 | 38.2 | 3,859 | 61.8 |

| Union | 2,519 | 59.0 | 1,750 | 41.0 |

| Williamsburg | 1,757 | 41.8 | 2,443 | 58.2 |

| York | 3,233 | 56.9 | 2,447 | 43.1 |

Dual governors

Hampton quickly organized his government and made a request to South Carolinians to refuse to pay taxes to the Chamberlain government. To support the Hampton government, each taxpayer was asked to contribute just 10% of what his tax bill had been the previous year. [16] South Carolinians, both white and black, paid taxes to the Hampton government and refused to pay taxes to the Chamberlain government, thereby denying the Chamberlain government its last legitimacy and authority apart from the U.S. Army.[17]

After the resolution 1876 presidential election in favor of Rutherford B. Hayes, both Chamberlain and Hampton traveled to Washington to discuss with the new president regarding the situation in South Carolina. President Hayes realized that only a massive reintroduction of federal troops would enable Chamberlain to continue as governor and thus ordered on April 3, 1877, for the removal of federal troops from South Carolina. The departure of Federal troops on April 10 caused Governor Chamberlain and the Republican led government to concede the election to Wade Hampton. A day later on April 11, Hampton became the sole and official governor of the state of South Carolina.

Timeline

1872

- November – Wade Hampton called for the redemption of the state after hearing of the election of Franklin J. Moses Jr. for Governor.

1876

- January 6 – Meeting of the Democratic State Committee to reorganize and agree to prepare for the Democratic convention in May.

- April 12–April 14 – Republicans held a state convention in Columbia to elect delegates to the National Convention in Cincinnati.

- May 4–May 5 – Democrats held a state convention in Columbia to elect delegates to the National Convention in St. Louis.

- July 8 – In the Hamburg Massacre in Aiken County, following arguments over a black National Guard parade on Independence Day, white paramilitary groups came to the black-majority town, where they killed 6 blacks, 4 while held as prisoners. One white died in an exchange of gunfire at the armory.

- August 15–August 17 – Democratic convention in Columbia adopted a platform and selected Wade Hampton as their nominee for governor in the general election.

- September 6 – Following a Democratic meeting in Charleston with a black speaker, a white fired above a black crowd, attracting more black Republicans, and a fight ensued, quickly increasing in size. In the riot, black Republicans injured 12 whites; the one white death is attributed to a mistaken shot by a white man.[14]

- September 13–September 15 – Republican nominating convention met in Columbia and selected Governor Chamberlain as their nominee for governor in the general election.

- September 16–September 19 – Extended acts of violence at Ellenton in Aiken County, where 500-600 white paramilitary came from Columbia County, Georgia; 1 white is killed and 40-100 blacks.[18]

- October 4 – Governor Chamberlain signed a document stating that he had no effective control of state government and was entirely dependent upon Federal troops. He threatened to use the soldiers to bring economic damage to the state if he was not elected Governor of South Carolina.[19]

- October 7 – Governor Chamberlain institutes martial law in Barnwell and Edgefield counties; he ordered the rifle clubs to disperse and forbids any unorganized militias.

- October 16 – At a "joint discussion meeting" near Cainhoy, organized by Republicans and Democrats in black-majority Charleston County, whites find hidden black arms and kill 1 black man. Black Republicans go to their hidden arms (rifles and shotguns) and attack the white men, who were armed only with pistols as they retreated to their steamboat. Republicans killed 6 whites and injured 16. It was the only such incident in which more whites than blacks were killed.[14]

- October 17

- President Ulysses S. Grant placed the Federal troops in South Carolina under the command of Governor Chamberlain.

- A party of black militia ambushed 6 white men leaving a Democratic meeting in Edgefield, killing 1 and wounding another.

- October 23 – A black mob laid siege to the town of Mt. Pleasant for the night, forcing the white citizens into a single house. The mob left in the morning threatening to return and kill everyone in the town.

- November 7 – Election day.

- November 8 – Black Republicans attacked whites on Broad Street in Charleston when somebody yelled incorrectly that white Republican leader Edmund W.M. Mackey had been killed. In the altercation, 1 white was killed and 12 were wounded; 1 black was killed and 11 were wounded.

- November 22 – State Board of Canvassers throws out the results from Edgefield and Laurens counties.

- November 28 – Governor Chamberlain orders Federal troops to occupy the State House to prevent the recently elected Democratic majority in the House of Representatives from taking power. The Democratic members left the State House and organized at Carolina Hall.

- November 30 – The Democratic legislators returned to the State House and assumed leadership of the House of Representatives. However, the Republican members threatened violence and the Democratic members left the chamber.

- December 3 – The Republican House of Representatives planned to eject the Democratic members from Edgefield and Laurens counties through the use of force by the black "Hunkidori Club" in Charleston. The plot was discovered by the Democrats and more than 5,000 white men from all over South Carolina assembled in Columbia to prevent the removal of the members.

- December 4 – The Democrats adjourned and left the State House, returning to Carolina Hall in order to prevent bloodshed.

- December 5 – Republican led General Assembly elects Chamberlain as governor.

- December 6 – South Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the Democrat, William H. Wallace, was the legally elected Speaker of the House. The commander of the Federal troops in the State House declared that he would ignore the decision of the Supreme Court and exclude the Democratic members from the House.

- December 7 – Governor Chamberlain inaugurated as the Governor of South Carolina for a second term.

- December 14 – The Democratic legislators tabulated the votes and declared Wade Hampton Governor of South Carolina by 1100 votes. He took the oath of office for governor and was inaugurated on the same day.

- December 20 – Governor Chamberlain issues a pardon for Peter Smith at the State penitentiary. The South Carolina Supreme Court ruled on appeal that Governor Chamberlain was not the legally elected Governor of South Carolina and therefore not entitled to the powers of the office.

- December 22 – The Republican led General Assembly adjourned.

- December 29 – Senator John Brown Gordon of Georgia proposed a resolution in the US Senate to declare Wade Hampton III as the lawful Governor of South Carolina.

1877

- January 17 – Senator John J. Patterson of South Carolina replied to the resolution of Senator Gordon by submitting papers that Governor Chamberlain was the legally elected Governor of South Carolina.

- February 9 – Governor Hampton issues a pardon for Tilda Norris, but the superintendent of the state penitentiary refuses to recognize Hampton as governor and does not release her.

- February 20 – President Grant orders for there to be no parades of the rifle clubs in honor of George Washington's birthday on February 22.

- March 7 – The South Carolina Supreme Court ruled that Wade Hampton III was the legally elected governor of South Carolina and was entitled to the powers of the office. After the ruling, Tilda Norris was released.

- March 31 – Hampton and Chamberlain meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes to discuss the situation in South Carolina.

- April 3 – President Hayes orders the removal of Federal troops from South Carolina.

- April 10 – Federal troops leave the State House and return to their barracks.

- April 11 – At noon, Wade Hampton becomes the sole and official Governor of South Carolina.

See also

- Governor of South Carolina

- List of Governors of South Carolina

- South Carolina gubernatorial elections

Notes

- ↑ Drago, p66

- ↑ Drago, p8

- ↑ Reynolds, p363

- ↑ Reynolds, p367

- ↑ Drago, p9

- ↑ Jarrell, p68

- ↑ Jarrell, p70

- ↑ W. Scott Poole, "Religion, Gender, and the Lost Cause in South Carolina's 1876 Governor's Race: 'Hampton or Hell!'", Journal of Southern History, Aug 2002, Vol. 68 Issue 3, pp 573-98

- ↑ Stephen E. Cresswell, Rednecks, redeemers, and race: Mississippi after Reconstruction (2006)

- ↑ Drago, p35

- ↑ Drago, p29

- ↑ Drago, p42

- ↑ Reynolds, p374

- 1 2 3 4 Melinda Meeks Hennessy, "Racial Violence During Reconstruction: The 1876 Riots in Charleston and Cainhoy", South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 86, No. 2, (April 1985), 104-106 (subscription required)

- ↑ Edgar, p404

- ↑ Walter Brian Cisco, "Wade Hampton: Confederate Warrior, Conservative Statesman," Potomac Books, Inc., Washington, D.C., 2004, p. 259

- ↑ Walter Edgar, '"South Carolina: A History p 405

- ↑ Mark M. Smith, "'All Is Not Quiet in Our Hellish County’: Facts, Fiction, Politics, and Race – The Ellenton Riot of 1876," South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 95, No. 2 (April 1994), 142-155 (subscription required)

- ↑ Reynolds, p444

References

- Drago, Edmund L. (1998). Hurrah for Hampton!: Black Red Shirts in South Carolina during Reconstruction. University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-541-1.

- Edgar, Walter (1998). South Carolina A History. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-255-6.

- Holt, Thomas (1979). Black over White: Negro Political Leadership in South Carolina during Reconstruction. University of Illinois Press. pp. 173–207. ISBN 0-252-00775-1.

- Jarrell, Hampton M. (1969). Wade Hampton and the Negro. University of South Carolina Press.

- Poole, W. Scott, "Religion, Gender, and the Lost Cause in South Carolina's 1876 Governor's Race: 'Hampton or Hell!'" Journal of Southern History Volume: 68. Issue: 3. 2002. pp 573+. online edition; in JSTOR

- Reynolds, John S. (1969). Reconstruction in South Carolina. Negro University Press. ISBN 0-8371-1638-4.

- Simkins, Francis Butler, and Robert Hilliard Woody. South Carolina During Reconstruction (1932)

- Rogers Jr., George C. and C. James Taylor (1994). A South Carolina Chronology 1497–1992. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-971-5.

- Williamson, Joel. After Slavery: The Negro in South Carolina During Reconstruction, 1861-1877 (1965)

- Zuczek, Richard. State of Rebellion: Reconstruction in South Carolina (1998)

Primary sources

- "The Vote in 1876 and 1878". The News and Courier. 3 November 1880. p. 2.

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Privileges and Elections. South Carolina in 1876: Report on the Denial of the Elective Franchise in South Carolina at the State and National Election of 1876, to Accompany Senate Miscellaneous Document 48, Forty-Fourth Congress, Second Session (Washington, D.C., 1877)

External links

- SCIway Biography of Governor Wade Hampton III

- SCIway Biography of Governor Daniel Henry Chamberlain

- Testimony as to the Denial of the Elective Franchise in South Carolina at the Elections of 1875 and 1876, Taken under the Resolution of the Senate of December 5, 1876 – US Congressional Serial Set 44th-2nd S.misdoc 48: Volume 1 Volume 2 Volume 3

- Report of the House of Representatives Regarding the Recent Election in South Carolina – US Congressional Serial Set 44th-2nd H.misdoc 175: House Report

| Preceded by 1874 |

South Carolina gubernatorial elections | Succeeded by 1878 |