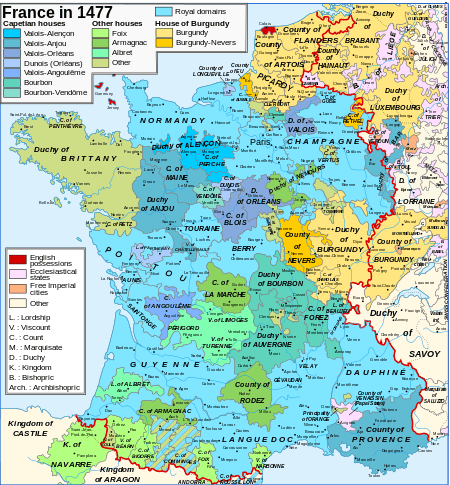

Territorial evolution of France

This article describes the process by which the territorial extent of metropolitan France came to be as it is since 1947. The territory of the French State is spread throughout the world. Metropolitan France is that part which is in Europe.

Occidental France, which arose from the Treaty of Verdun of 843, remained stable for many years. The first kings, the Capetians, were too much occupied with imposing their authority in their own realm to be expansionist. They deftly exploited dissent among their turbulent vassals, applying pressure on them and on the Church and towns. The great conflicts with the kings of England were important occasions for asserting royal power. The 13th century re-annexations of Normandy and of Languedoc to the French kingdom were two important stages in the unification of the kingdom.

France soon lost the County of Barcelona (Catalonia), from the end of the 9th century. The crossing beyond Rhone, which for a long time remained the frontier, did not begin until the 14th century, with the purchase of the Dauphiné. Louis XI regained his inheritance of the two most powerful prerogatives granted to cadet branches of the dynasty: Burgundy and Anjou including Provence in the Holy Roman Empire (1481–1482).

The marriage of Anne of Brittany first with Charles VIII then with Louis XII led finally to the effective annexation in 1532, of her duchy which was already within the ambit of the French Kingdom but which had hitherto firmly maintained its distinct existence.

From 1635 to 1748, Richelieu and Louis XIV undertook an expansion of the frontiers of the kingdom towards the north and towards the Rhine. Their aim was to check the aspiration of the Austrian royal house towards its own predominance in Europe. The loss of French Flanders (1526) had brought the frontier dangerously close to the French capital. Alsace, Artois and Franche-Comté were annexed between 1648 and 1697. The Duchy of Lorraine remained some time an enclave in the French kingdom before it too was incorporated in 1766. This and the purchase of Corsica in 1768 brought the territory of the kingdom into a consolidated block.

During the period of the French Revolution and First Empire, France expanded temporarily on the left bank of the Rhine. The frontier in the north east lost its definition. On the whole, it remained stable from 1697 to 1789 when it became vague, following no particular line. It was re-established, more or less on its old line in 1815, by the Congress of Vienna. France did lose some places such as Landau and Saarlouis. These strategic losses and the construction of a powerful German state may be seen as giving rise to later diplomatic and military events. But even after the Armistice of 1918, France was unable to make new territorial gains towards the north-east, into the Saarland.

Subsequently in the 19th century, there were only a few developments. The Duchy of Savoy and the County of Nice were definitively re-attached to France, by plebiscite in 1860. Alsace-Lorraine was annexed by Germany in 1871 but became French again in 1918.[1]

Other alterations were made temporarily, by the occupying power, during the period of World War II.

Geographical context

Modern Metropolitan France lies to a large extent, within clear limits of physical geography. Roughly half of its margin lies on sea coasts. In the south-west, its border lies among the peaks of the Pyrenees mountain range. Similarly, in the south-east it lies in part of the Alps. In the East it follows one or another of the Jura ranges until it reaches the River Rhine, which it follows downstream. The remaining section, in the north-east, between the Rhine and the North Sea, is provided with the least clear natural definition.

The Middle Ages (843–1492): the unification of the kingdom

The great feudal domains

The Treaty of Verdun of 843 marked the appearance of France and Germany. The arrangement was seen as a temporary sharing out of the inheritance between the heirs of Charlemagne. It set a seal to the creation of the borders of two states each of which would have its own development. Their common frontier at that time, was placed approximately along the Saône and the Rhône.

On the one side, the first Germanic monarchy would weaken itself in trying to re-establish the Carolingian Empire without having sufficient means. On the other hand, the French monarchy would from a modest base, slowly establish itself, ultimately to take the leading role in Western Europe.

In 987, the Carolingians were ousted in France by the election of Hugues Capet who imposed his dynasty. The royal domain of the first Capetians was initially limited to a part of the Île-de-France, between Paris and Orléans, which were its principal towns.

Elsewhere, it was the great lords who exercised their authority, notably the six lay peers of France : the dukes of Aquitaine, of Burgundy and of Normandy, besides the counts of Champagne, of Flanders and of Toulouse.

The first objective of the Capetian kings was the consolidation of their regional authority, which they tried to do in the course of the 11th and 12th centuries. The principal enlargement of the royal domain in the course of that period was the purchase of the Viscounty of Bourges in 1101 which was to become the Duchy of Berry.

Consolidation of royal power when faced with the Kings of England

Expansion of the royal domain in the 13th century

The struggle against the Norman and Angevin kings of England was the opportunity for the kings of France to extend their authority. They had, it is true, to face up to the formidable challenge with which they were presented. The Duke of Normandy William the Conqueror became King of England in 1066 through his victory at Hastings over the Saxons. On the extinction of his male line of descent, his heir was the Duke of Anjou, Henry Plantagenet, grandson by his mother of Henry I of England. Two months before he ascended to the English throne, as Henry II, he married Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine, the richest heiress in the French kingdom and ex-wife of the King of France. The kings of France nevertheless, held some trump cards: the prestige and prerogatives of their position, the dissent at the heart of the Plantagenet family and the difficulty the latter had in exacting obedience in the South-West.

John Lackland, son of Henry II, caused confusion among his vassals by his irregular and violent behaviour.

The king of France, Phillip Augustus was able to take advantage of this by taking Normandy from him by his capture of the fortress of the Château Gaillard, downstream from Paris (1204).

The conquest of that province was vital as it increased the revenues of the French Crown substantially. Philip Augustus was in fact the first king of whom the authority extended beyond the Île de France. The extent of his field of action and its effectiveness of his authority were enhanced. The king subdued notably, the County of Vermandois, Touraine and the key parts of the County of Auvergne. The last was entrusted to several lords of the royal entourage before being formally reattached to the royal domain in 1531. The success of Philip Augustus was confirmed by his victory over the Holy Roman Emperor at Bouvines in 1214.

Shortly afterwards, The King of France Louis VIII the Lion exploited the Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars of the Midi to impose his authority on the County of Toulouse (1229). This new conquest was to become the province of Languedoc and until The Revolution, comprised essentially eight of the modern French départments in the Midi. Thanks to the troubles of the end of the mediaeval period, Languedoc was to obtain the establishment of its own institutions: a parliament (which was a sovereign court of justice) and États, that is States: assembly which voted on taxes and which decided on communal investments.

The cumulative effect of these conquests was to prompt the kings to appoint their younger sons to territories: the apanages or privileges. This policy would allow the kings to progressively impose royal authority on the provinces, since in practice, the apanages would return without difficulty, to the crown whether by inheritance or by confiscation. This happened for example, in Poitou, in 1271 and Anjou, in 1481. These were two provinces taken by conquest from the kings of England by Phillip Augustus and Louis VIII.

Difficulties of the late medieval period

Occasionally, the apanage policy weakened the royal power. When the French king, Charles VI, was in conflict with his brother, Louis of Orléans, their cousin, Jean Sans Peur, duke of Burgundy, tried to impose himself on the government through a series of violent strikes. He progressively attracted the hostility of the rest of the group of the royal princes and was ousted. With a surprise attack in 1418, he seized Paris, forcing the heir to the throne, the future Charles VII, to flee to Bourges. Similarly, counts of the very rich county of Flanders (at this stage, they were the dukes of Burgundy) used their position as top rank peers of France to establish a powerful state. Their policy was facilitated by the fragmentation of power in France and in Germany, at the end of the Middle Ages. The duchy of Burgundy's holdings in the Netherlands were the precursor of the modern Belgium.

However, the kings of England remained dukes of Aquitaine. When Philip IV died, his nephew, Philip I count of Valois mounted the throne of France in the end, as Philip VI. Philip IV had married Jean of Champagne, who brought Champagne with her into the royal domain (1284). They had two sons but a new series of conflicts, known as the Hundred Years' War, was provoked by the claim of Edward III of England, grandson of Philip IV through Edward's mother. Edward's aim was to supplant Philip VI. French armies suffered heavy defeats at Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356). Later, a third serious defeat was suffered at Agincourt (1415). Having temporarily lost territory as a result of the Treaty of Brétigny, the kingdom was again divided by the Treaty of Tours (1420). But a new spirit was born in Joan of Arc who obliged the English king to raise the Siege of Orléans (1429). Having been crowned at Reims, Charles VII returned to Paris and finally established his authority in the South West, that is to say Aquitaine, taking Bordeaux and Bayonne (1453) from the English king.

Expansion towards the Alps

The Holy Roman Empire, which is represented in the modern world by Germany, sank into political anarchy during the 13th century. This opened the way to all sorts of encroachment.

Philip IV joined the town of Lyon to his realm again (1312). It was a former capital of the Gauls and an important crossroads in European commerce.

The unhappy Phillip VI bought the Dauphiné on 30 March 1349, by the treaty of Romans.

His grandson, the brother of Charles V, Louis was invested as Duke of Anjou. He was further adopted as heir by the Countess of Provence and Queen of Sicily, Joan. He accomplished his conquest of Provence in 1383-1384. His grandson, King René could not however, maintain his position in Italy and transferred his possessions to the King of France, Louis XI: Anjou in France and Provence in the Holy Roman Empire (1481).

Louis XI had the good sense not to adopt René's claims in Italy. That was not so in the case of his son Charles VIII who not only undertook an expedition to Naples which gave no result but beforehand, abandoned several of his father's conquests; Artois, Franche-Comté and Roussillon, to his eventual competitors.

The Early Modern period (1492–1789): conflicts with the Habsburgs of Spain and Austria

Integration of the last great feudal domains

On the one hand, the succession of the Duchy of Burgundy and on the other, the desire to gain a foothold in Italy were the cause of a first series of conflicts with the House of Austria, the Habsburgs. On the death of the last Duke of Burgundy, Charles the Bold, his possessions were divided. His daughter, Mary of Burgundy inherited the Burgundian Netherlands and the Burgundian part of the Franche-Comté. Louis XI took back the Duchy of Burgundy proper and Picardy (1482). The grandson of Mary, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V of Habsburg entered into conflict with Francis I of France.[2] They both wanted the Duchy of Burgundy as well as the Duchy of Milan.

This first phase was interrupted by the French Wars of Religion and it was not decisive for the French monarchy. After his defeat at Pavia in 1526, Francis I kept Burgundy but renounced in perpetuity, his suzerainty over the County of Flanders. The Burgundian Netherlands which Emperor Charles V had inherited, had hitherto been composed partially of French and partially of German territories. By the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, they became a separate political entity.

Meanwhile, Henry II of France consolidated the frontiers of the French kingdom by the occupation in 1552, of the towns of Metz, Toul and Verdun which became the province of the Three Bishoprics and the re-taking of Calais from the Queen of England (1558).

Elsewhere, the marriage of Louis XII with Ann of Brittany, followed by that of their daughter Claude to Francis I in 1514 permitted the attachment of the Duchy of Brittany to France again (1532).

At the time of his accession in 1589, Henry IV of France brought the possessions of the last remaining great feudal house, the Albrets, to the royal domain. He was the heir by his mother, Joan of Albret. These possessions were Béarn, Armagnac and Limousin.

Having each developed a strong identity, like Languedoc, these later additions, Béarn, Burgundy and Brittany retained their own institutions such as states and parliament, until the Revolution.

Expansion toward the east: the frontier on the Rhine

Toward new conflicts with the house of Austria

The house of Austria showed a wish for supremacy in Europe, giving an impression of a militant bastion of Catholicism faced with the emergent Protestant states. The French monarchy was more worried that this claim would find echoes in Catholic circles in France. Besides, Habsburg possessions encircled its territory: Spain, the Netherlands, Franche-Comté and more distantly, Milan. Until the Spanish Armada was defeated in 1588, it was not clear that England would not become part of this encirclement.

Henry IV of France had inherited a dispute with Spain. By his mother, he was heir to the kings of Navarre who had been dispossessed by the kings of Spain. They had been left with only Lower Navarre. From this time on, the kings of France carried also the title of 'king of Navarre'.

Before taking up the struggle again, Henry IV paid off the French adventure in Italy. In 1601, he intervened against Duke of Savoy who had supported plots against him. By the Treaty of Lyon, France acquired Bresse, Bugey, Valromey and the Pays de Gex, which together constitute the modern département of Ain. This was in exchange for the marquisate of Saluzzo, the last place he held in Italy. France had taken possession of Saluzzo in 1548, on the death of its last marquis. It had been claimed since the purchase of the Dauphiné.

However, the prospect of a conflict with the house of Austria offended a great part of the Catholics of France, notably the court. Marie de Médicis and the duke D' Épernon were notable members of this party. It was in this context that Henry was assassinated by a fanatic, Ravaillac, which put a stop to his project.

The wars of the 17th century

The king of France Louis XIII and his prime minister Richelieu retook the offensive in 1635 within the framework of the Thirty Years' War. A first, decisive war against Spain was marked by the victory at Rocroi in 1643.

The eastward expansion was aimed at cutting the lines of communication of France's enemies and to facilitate contacts with her allies in Germany, a country then comprising many small, more or less independent states.

Wars against the house of Austria followed each other and the several treaties resulting from them accumulated into a French grasp on several provinces of the Holy Roman Empire:

- The Peace of Westphalia (1648) had the effect of an annexation by France of the margraviate of Haute-Alsace, hitherto a Habsburg property, and of the Décapole, a federation of ten Alsatian towns. They also ratified the annexation of the Three Bishoprics, of Metz, Toul and Verdun, occupied since 1552.

- The Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) allowed the recovery of the County of Artois (with the exception of Aire of Saint-Omer), and of Roussillon: at this stage, the frontier with Spain became permanently defined.

- The first Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) in 1668 ended the War of Devolution. Louis XIV took the towns of Lille, Douai and Armentières from the Spanish, thereby allowing France a foothold back in Flanders.

- The Treaty of Nijmegen, signed 10 August 1678, ended the Franco-Dutch War. The great loser in the war was Spain, ceding to France a list of places - Franche-Comté, the forts on the Aire and Saint-Omer, Cambrai, Valenciennes and Maubeuge in Hainaut. From the time of the Revolution, these French lands in Flanders and Hainaut would become the département of Nord.

From 1680 to 1697, Louis XIV emboldened by his early successes, adopted a policy of unilateral annexations and groupings. The French even took part during the temporary conquest of Habsburg-ruled Luxembourg from 1684 to 1697.

By the Treaty of Rijswijk in 1697, which concluded the Nine Years' War, he had finally to renounce most of these newly-taken lands but retained Saarlouis and Lower Alsace, with the town of Strasbourg. The bulk of Alsace was thenceforward, entirely French. The exceptions were Mulhouse and some territories held by German princes.

Consolidation of territory

At the end of Louis XIV's reign, a balance seemed to have been achieved. The other European powers were no longer disposed to accept a new French expansion and were prepared to form alliances to oppose such a thing. The borders had been pushed out far from the French capital. On top of this, they were thenceforward defended by a network of modern fortresses constructed by Vauban. Fortified towns to the north of Lorraine (Montmédy, Thionville, Longwy, Saarlouis)[4] isolated the Duchy from other states of the German (Holy Roman) Empire so as to weaken the independence of the duke.

Since 1632, France had regularly occupied Lorraine in periods of war, without annexing it.[5] The duke, Charles IV, who was allied with the houses of Austria and Bavaria, adopted a policy hostile towards France. He and afterwards, his nephew, Charles V of Lorraine had been officers in the Imperial Austrian Army. It was only later that France was presented with both motive and a favourable occasion to annex the duchy. This was the marriage, in 1736, of Francis de Lorraine to the heiress of the Austrian imperial house, Archduchess Maria Theresa, at a moment when Austria was weakened. The Treaty of Vienna (1738) awarded Lorraine to Louis XV of France, who gave it for life, to his father-in-law, Stanisław Leszczyński. The duchy of Lorraine would be formally annexed to France in 1766, when Stanisław died. In recompense, Duke Francis III was given the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, which was vacant.

Through animosity towards the Habsburgs, France allowed itself to be drawn into the War of Austrian Succession again. However, after the victory at the Battle of Fontenoy, Louis XV renounced all his new conquests. In 1748, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) put an end to the rivalry of the French and Austrian monarchies.

In 1768, the Republic of Genoa ceded Corsica to Louis XV in exchange for annulment of a debt.[6]

Thus, on the eve of the Revolution, the modern, hexagonal shape of France was accomplished. However, the complexity of the feudal framework which governed the political organization under the Ancien Régime explains the survival of a number of foreign enclaves, particularly in the recent zone of expansion - Alsace, Franche-Comté and Lorraine.

L’Époque contemporaine

The French title of this section has been retained in translation from the French Wikipedia page because the apparently corresponding term in English has not quite the same meaning. English-speaking historians, though they define it otherwise, in effect, regard the term 'contemporary history' as meaning 'within living memory'. French writers on the other hand, are inclined to open the period with the French Revolution.

Transformation arising from the French Revolution (1789–1815)

Implementation of a new concept of national territory

The Revolution did away with the concept of ownership of political entities by individuals. France became one state rather than the aggregate of a mosaic of semi-states.

Suppression of the provinces and creation of the départements

As a means of loosening old ties of allegiance, and of rationalizing administration, the old divisions based on feudal ownership were replaced by départements of roughly uniform size and named after geographical features such as rivers. Even Paris was in the département of Seine. Nevertheless, in some cases such as Nord the modern département comprises broadly, the territory of one period of acquisition.

Reduction of enclaves

Several territories were foreign enclaves surrounded by the lands of the kingdom of France. The Convention nationale willed their merging into France, by treaty or regardless of the rights of the (mainly German) princely owners. Some of these treaties were:

- The Comtat Venaissin, property of the Holy See since 1274, unilaterally annexed in 1791, annexation recognised by the Pope in the treaty of Tolentino (1797).

- The County of Montbéliard added to Haute-Saône (1793).

- Riquewihr and the county of Horbourg belonging to the ruling family of Württemberg-Monbéliard, added to Haut-Rhin and the counties of Hanau-Lichtenberg, of La Petite-Pierre and of Sarrewerden, added to Bas-Rhin (1793)

- The principality of Salm-Salm joined to Vosges (1793).

- The counties of Créhange and of Dabo joined to Moselle (1793), as was the lordship of Lixing (1795).

- The republic of Mulhouse, affiliated to the Helvetic Confederation since 1515 and having become an enclave in Haut-Rhin, voted in favor of its reunion to France in 1798.

French domination in Europe

Tempting prizes beyond the natural boundaries of The Alps, Jura, Pyrenees and Rhine (1789–1799)

The institution of a revolutionary regime in France led most of the European monarchies to form coalitions against it. The military successes of the armies of the First Republic resulted in a considerable expansion of the national territory.

- The Comtat Venaissin: 1791;

- The Duchy of Savoy: 1792;

- The County of Nice, the County of Montbéliard and the Principality of Salm-Salm: 1793;

- The Austrian Netherlands and the Prince-Bishopric of Liège: 1795;

- The German states on the left bank of the Rhine: 1797.

- The Republic of Geneva and the Republic of Mulhouse: 1798;

Most of these annexations were to be lost subsequently, at the Congress of Vienna (1815).

Conquests during the period of the Consulate and of the Empire (1799–1815)

Under Napoleon Bonaparte the conquests continued. They were principally motivated by the aim of controlling the coasts of Europe, based on the idea of the natural borders of France. This was in the context of the struggle against the United Kingdom and the commercial blockade which that country imposed.[7] In that way, the following were annexed:

- Piedmont 1802, the king of Sardinia having taken refuge in his island.

- Ligurian Republic 1805.

- The Kingdom of Etruria and the Duchy of Parma 1808.

- The Papal States 1809.

- The Kingdom of Holland and the Valais 1810.

- The German North Sea coast (Hanover, Oldenburg) with the ports of Bremen, Hamburg, even Lübeck on the Baltic coast, in 1811.

- Catalonia was segregated from Napoleonic Spain and attached to France in 1812.

An appraisal after the Congress of Vienna (1815): the Treaty of Paris (1815)

Nearly all the conquests since the Revolution were restored to their former owners. France was virtually returned to its borders of 1791, except that she retained the former enclaves. the Comtat Venaissin with Avignon, Mulhouse and Montbéliard.

The other European powers were watchful lest France should ever regain control of the left bank of the Rhine (below the River Lauter):

- The bulk of the German territories in the left (West) bank was restored to Prussia despite the distance from the Prussian centre and the difference in cultures.

- A new state was created: the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg, of which the citadel served as an outpost of the Prussian army.

- France lost several strongholds covering her frontiers: Bouillon (Ardennes NE of Sedan), Saarlouis (Saarland NW of Saarbrücken), Landau (Rhineland NW of Karlsruhe) and so on.[8]

Unification of Italy (1860) and the reunification of Germany (1866–1871): the effects

Intervention of France in Italy[9]

Reunification of Savoy and of the County of Nice (1860) with France

Following discussion at Plombières, of 21 July 1858, the minister of the Estates of Savoy Camillo Cavour promised Napoleon III the Duchy of Savoy and the county of Nice, in exchange for French support in the policy of the unification of Italy (the Risorgimento), led by king Victor-Emmanuel II of Savoy. That proposition was made official by a treaty at Turin, dated December 1858. It was actually signed in January 1859.

Following the victories over Austria in 1859 (Magenta and Solferino),[10] and the armistice of Villafranca, Austria ceded Lombardy to France, who ceded it immediately to Piedmont/Sardinia, Napoleon III took back Savoy and Nice. With the Treaty of Turin, 24 March 1860, Victor-Emmanuel consented to ceding the duchy of Savoy and the county of Nice, after consulting the populations, which took place in April 1860. The king released his Savoyard subjects following the plebiscite of the same month.

Modifications of the Monaco frontier (1861)

Since 1848, Menton and Roquebrune, then integral parts of the principality of Monaco, declared themselves to be free towns and were occupied by a Sardinian garrison. Following the secession by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia of the Duchy of Savoy and of the County of Nice to France in 1860, the inhabitants of Roquebrune and Menton, towns considered in the circumstances as forming part of the County of Nice, chose by referendum, to be reunited with France.

On 2 February 1861, Prince Charles III of Monaco and Napoleon III signed a treaty at Paris by which, in exchange for 4,000,000 francs, the prince and his successors would renounce in perpetuity, in favour of the Emperor of the French, all rights direct and indirect on these two communes.[11]

France's position on Prussia's reunification of Germany

The Luxembourg Crisis

Alsace-Lorraine : contention between France and Germany (1871–1918 1940–1945)

Following the Franco-Prussian War, of 1870 and by virtue of the Treaty of Frankfurt (10 May 1871), all of Alsace excepting the Territory of Belfort, was annexed by Germany, as were the districts of Sarreguemines, Metz, Sarrebourg (less 9 communes), Château-Salins (less 10 communes) and 11 communes of the arrondissement of Briey in Lorraine and the cantons of Saales and Schirmeck in the Vosges; a total of 1,447,000 hectares; 1,694 communes and 1,597,000 inhabitants. These territories would be recovered at the end of the First World War.[12]

Alsace-Lorraine was annexed de facto to the Third Reich on 27 November 1940. Though the main towns of Alsace-Lorraine were liberated during the autumn of 1944, by troops of Generals Koenig and Leclerc, fighting raged on in the Colmar Pocket until 2 February 1945.

The National territory since 1945

The Treaty of Paris with Italy (1947), last general revision of a French frontier

In 1947, in the Treaty of Paris, France gained about 700 km², in five extensions of the national territory in the départements of Alpes-Maritimes, Hautes-Alpes and Savoie:

- annexation of the Tende Valley, which had remained Italian when the County of Nice became French in 1860. The border here now follows the main crest of the Alps. The département of Alpes-Maritimes saw its area extended by 560 km².

- the upper valley of the Roya, that is the communes of Tende and La Brigue,

- the hamlets of Libre, Piène-Basse and Piène-Haute (commune of Breil-sur-Roya),

- the hamlet of Mollières (commune of Valdeblore),

- the upper valleys of the Vésubie and the Tinée;

- displacement by several kilometres of the Italian border in the Mont-Cenis massif, thereby increasing French territory by 81.8 km², on the commune of Lanslebourg, Bramans and a small area in favour of the commune of Sollieres-Sardières, Savoie. From this time on, the frontier has no longer followed the line of the crest but is on the slope of the Italian side. The Mont-Cenis Dam and reservoir, subsequently constructed on its slopes, is thus in France though on the Italian side of the ridge.

- annexation of the summit of Mont Thabor and its eastern slopes, notably the upper basin of the Vallée étroite (narrow valley), in the commune of Névache, Hautes-Alpes (47 km²).

- annexation of Mont Chaberton (17.1 km²), in the commune of Montgenèvre (Hautes-Alpes), notably of an Italian fort, destroyed by French forces at the opening of the Second World War.

- annexation of the western part of the Little St. Bernard Pass following the watershed. (3.22 km²), to the benefit of the commune of Séez, Savoie.

It should be noted that though the Paris Treaty settled disputes on these five points in the line of the border, in the area of the summits of Mont Blanc and Mont Blanc de Courmayeur, questions remain open.

Appendix: minor modifications to the frontiers since 1815

This appendix contains details of minor revisions of the French borders with Andorra (2001), Luxembourg (2006), Switzerland (1862) and (1945 to 2002).

Maps showing the development of the territory

-

France in Europe from 843 to 870

France in Europe from 843 to 870 -

France in the early 11th centuryFrench royal domain

France in the early 11th centuryFrench royal domain -

France at the end of the 12th centuryFrench royal domain

France at the end of the 12th centuryFrench royal domain -

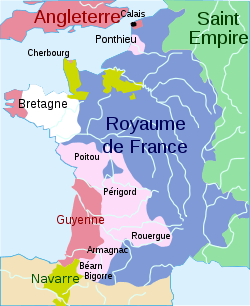

France in 1328

-

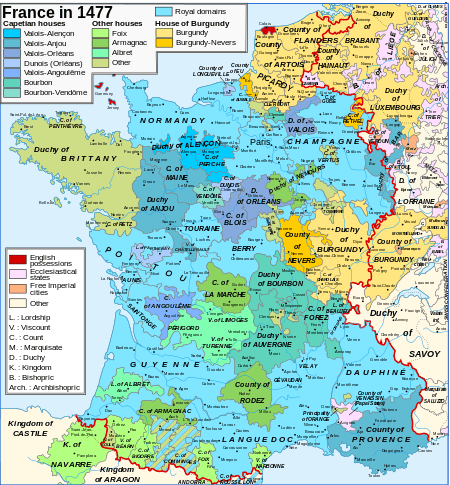

France at the end of the 15th centuryFrench royal domain

France at the end of the 15th centuryFrench royal domain -

Frontiers of France: 1601 to 1766

-

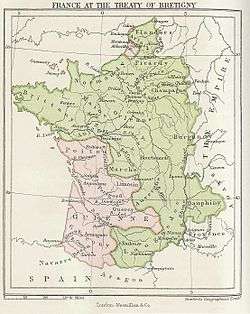

Territorial conquests from 1552 to 1798

-

France in 1810 under Napoléon. All shades of blue = states operating a blockade against the U.K.France

France in 1810 under Napoléon. All shades of blue = states operating a blockade against the U.K.France

See also

- Crown lands of France

- Philip II of France

- Hundred Years' War

- Cardinal Richelieu

- Thirty Years' War

- Malgré-nous

- French colonial empire

Footnotes

- ↑ Lorraine is the French name for Lotharingia, it was that part of Charlemagne's empire which was allocated to Middle Francia. Subsequent generations divided this again and again. France was the successor state of West Francia, while East Francia came to be represented by Germany. With the rise of the 19th century empires, the territory of Middle Francia became an article of contention between them. (For link to a map of the three Francias, see right of window.)3 Francias

- ↑ He was the French king who met Henry VIII of England at the Field of the Cloth of Gold

- ↑ This fragmentation is shown in more detail in the Holy Roman Empire map (see right edge of window) but at high resolution it is slow.

Holy Roman Empire 1648

Holy Roman Empire 1648 - ↑ The fortress at Saarlouis was typical of those designed by Vauban. (see right of window for link to a plan)

Saarlouis Fort

Saarlouis Fort - ↑ For an example of these efforts, see Lines of Weissenburg.

- ↑ This made Napoleone di Buonaparte a Frenchman.

- ↑ See a little of the context. In these circumstances, in Britain, it was as blockade runners and smugglers that the chasse-marées came to wider notice than just among seamen, who already knew of them and their association with Breton fishing fleets.

- ↑ Alexandre Vuillemin's map of 1843 illustrates the state of development of the French borders after the Congress of Vienna. She then numbered 86 départements and possessed Alsace-Lorraine but no longer Savoy or Nice. (see right of window for link to an electronic copy)

France 1843

France 1843 - ↑ There is a detailed article in French.

- ↑ Solferino was the battle which inspired Henri Dunant to found the Red Cross

- ↑ The link at the right of the window is to a map of the County of Nice showing the area of the Kingdom of Sardinia annexed to France in 1860 (light brown) and to Italy (yellow). The maroon area was already part of France before 1860.

Nice 1860

Nice 1860 - ↑ Treaty of Versailles (1919) Article 27. See French Wikipedia, fr:Traité de Versailles (1919) (Traité de Versailles (1919): Remaniements territoriaux)