Typhoon Karen

| Category 5 (Saffir–Simpson scale) | |

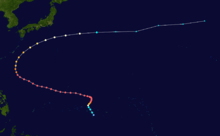

Typhoon Karen on November 14 | |

| Formed | November 7, 1962 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | November 18, 1962 |

| (Extratropical after November 17, 1962) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 295 km/h (185 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 894 hPa (mbar); 26.4 inHg |

| Fatalities | 11 total, 26 missing |

| Damage | $250 million (1962 USD) |

| Areas affected | Guam, Mariana Islands, Taiwan, Ryukyu Islands |

| Part of the 1962 Pacific typhoon season | |

Typhoon Karen was the most powerful tropical cyclone to strike the island of Guam, and has been regarded as one of the most destructive events in the island's history.[1] It was first identified as a tropical disturbance on November 6, 1962, well to the southeast of Truk. Over the following two days, the system tracked generally northward and quickly intensified. Karen became a tropical storm late on November 7, and within two days it explosively intensified into a Category 5-equivalent super typhoon on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale. Turning westward, the typhoon maintained its intensity and struck Guam with winds of 280 km/h (175 mph) on November 11. Once clear of the island, it strengthened slightly and reached its peak intensity on November 13 with winds of 295 km/h (185 mph) and a barometric pressure of 894 mb (hPa; 26.40 inHg). The storm then gradually turned northward as it weakened, brushing the Ryukyu Islands on November 15, before moving east-northeastward over the open waters of the Pacific. Karen continued to weaken and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on November 17 before losing its identity the following day between Alaska and Hawaii.

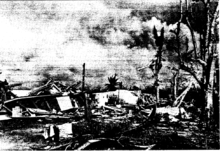

Karen devastated Guam with wind gusts estimated up to 280 km/h (185 mph). Ninety-five percent of homes were damaged or destroyed, leaving at least 45,000 people homeless. Communication and utilities were crippled, forcing officials to set up water distribution centers to prevent disease. Total losses on the island amounted to $250 million.[nb 1] Despite the severity of the damage, only 11 people were killed. In the wake of the storm, a massive relief operation evacuated thousands to California, Hawaii, and Wake Island. Thousands more were sheltered in public buildings, and later tent villages, for many months. More than $60 million in relief funds were sent to Guam over the following years to aid in rehabilitation. Though the storm was devastating, it spurred new building codes and a revitalized economy.

Meteorological history

On November 6, 1962, a tropical disturbance was identified over the Pacific Ocean several hundred miles south-southeast of Truk, in the Federated States of Micronesia, by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC).[2] Tracking northwestward, the disturbance intensified and was classified as a tropical depression early on November 7.[3] Later that day, the system passed to the east of Truk and turned due north before attaining gale-force winds. Around 18:00 UTC, the JTWC issued their first advisory on Tropical Storm Karen, the 27th named storm of the 1962 season. Several hours later, a reconnaissance mission into the storm revealed a partially closed 35 km (22 mi) wide eye. Over the following 30 hours, Karen underwent a period of explosive intensification as its eye became small and increasingly defined.[2] Between 00:00 UTC on November 8 and 03:40 UTC on November 9, Karen's barometric pressure plummeted from 990 mbar (hPa; 29.24 inHg) to 899 mb (hPa; 26.55 inHg), a drop of 91 mb (hPa; 2.69 inHg).[2][3] At the end of this phase, Karen featured an 8 to 10 km (5 to 6 mi) wide eye and had estimated surface winds of 295 km/h (185 mph), ranking it as a modern-day Category 5-equivalent super typhoon on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale.[2]

After attaining this initial peak intensity on November 9, Karen weakened somewhat as it gradually curved west-northwestward. By 15:14 UTC, the storm began to undergo an eyewall replacement cycle as a larger secondary eyewall, approximately 64 km (40 mi) in diameter, started developing.[2] Although the storm's winds failed to drop significantly, Karen's central pressure rose to 919 mb (hPa; 27.14 inHg) during this phase.[3] Accelerating slightly, Karen tracked steadily west-northwestward towards Guam. By November 11, the system had regained a well-defined eye and deepened once more.[2] Between 12:10 and 12:35 UTC on November 11, the 14 km (9 mi) wide eye of Karen passed directly over southern Guam.[1] At this time, the storm was estimated to have had winds of 280 km/h (175 mph),[3] which would have made it the most intense typhoon to strike the island since 1900. However, years of post-storm analyses have indicated that it may have been somewhat weaker when it passed over Guam.[1] At the Weather Bureau station at the north end of Guam, a pressure of 942.4 mb (hPa; 27.83 inHg) was measured. Farther south at Anderson Air Force Base, 939.7 mb (hPa; 27.75 inHg) was recorded. The lowest verified pressure was 931.9 mb (hPa; 27.52 inHg) at the Agana Naval Air Station. Closest to the eye was Naval Magazine where a pressure of 907.6 mb (hPa; 26.80 inHg) was estimated but never verified.[4]

Continuing west-northwestward, Karen attained its peak intensity on November 13 with a central pressure of 894 mb (hPa; 26.40 inHg).[3] Between November 13 and 14, Karen gradually turned towards the north as it underwent another eyewall replacement cycle.[2][3] During this time, Karen finally weakened below Category 5 status as its winds dropped below 251 km/h (156 mph).[3] This marked the end of its near-record 4.25-day span as a storm of such intensity, second only to Typhoon Nancy of 1961 which maintained Category 5 status for 5.5 days.[5] Over the following days, the typhoon's structure gradually became disorganized, with its eye no longer well-defined by November 15.[2] By this time, Karen began accelerating northeastward and later east-northeastward over the open ocean.[3] The combination of its rapid movement and entrainment of cold air into the circulation ultimately caused the system to transition into an extratropical cyclone on November 17.[2][6] The remnants of Karen continued tracking east-northeast and were last noted by the JTWC on November 18 roughly halfway between the southern Aleutian Islands and northern Hawaiian Islands.[2][3]

Impact

Guam

"It was just hell. It was total destruction. It looked to me like a whole army of workers with big scythes had just gone across the whole place and chopped down everything they could see. Everything was lying down–smashed. Even the forests were lying down."

Colonel William H. Lewis[7]

Following the identification of a tropical disturbance on November 6, a level four Typhoon Condition of Readiness (TCOR), the lowest level of alert, was raised for Guam. By November 8, three days prior to Karen's arrival, this was raised to level three, prompting residents and military personnel to stock up on supplies.[8] A public announcement was made that day as well, warning residents that the typhoon would likely strike the island.[9] At 9:00 p.m. on November 10 (11:00 UTC), a level two TCOR was put in place for Guam and a typhoon emergency was declared. Buildings were boarded up and emergency supplies were distributed.[8] By 8:00 a.m. (22:00 UTC on November 10), this was raised to level one, the highest level of warning.[2] At this time, the USS Haverfield, USS Brister, USS Wandank, and USS Banner sought refuge from the storm over open waters.[8] All personnel on the island were ordered to evacuate to typhoon-proof shelters and emergency rations were prepared.[2] Strategic air command planes stationed on the island were relocated to avoid damage.[10] Many residents on the island sought refuge in government buildings designed to withstand powerful storms while others evacuated to Wake Island.[11] Roughly 24 hours after the typhoon's passage, all warnings were discontinued.[8]

Striking Guam as a Category 5-equivalent typhoon, Karen produced destructive winds across much of the island.[1] With the eye passing over the southern tip of the territory, the most intense winds were felt over central areas. Wind gusts over the southern tip of Guam were estimated to have peaked around 185 km/h (115 mph).[12] Due to the extreme nature of these winds, all anemometers on the island failed before the most intense portion of the storm arrived, and there were no measurements of the strongest winds; however, post-storm reports estimated that sustained winds reached 250 km/h (155 mph) in some areas. The highest measured gust was 240 km/h (145 mph) at a United States Navy anemometer on Nimitz Hill just before 11:00 UTC on November 11, roughly two hours before the typhoon's eye passed the station. Based on this measurement, a study in 1996 estimated that gusts peaked between 280 and 295 km/h (175 and 185 mph) over southern areas of the island.[1] Newspaper reports indicated that a gust of 272 km/h (169 mph) was measured on the island before the anemometer was destroyed.[9] There was also an unverified report of a 333 km/h (207 mph) wind gust.[13] Nearly all measurements of rainfall during the typhoon were lost; the only known total is 197 mm (7.76 in) at the Weather Bureau station for the period of November 10–12.[4]

Surveys of damage revealed belt-like damage patterns from the winds, with some homes being leveled and others nearby having only minor damage, akin to the impacts of tornadoes.[12] The winds uprooted and snapped palm trees across the island and, in some instances, stripped the bark of tree trunks and branches as if they had been sandblasted.[1] Vegetation was completely defoliated across central areas of the island. In some places, it was described as the aftermath of a forest fire.[12] The winds also blew debris across the island. Metal roofing was found wrapped around trees.[8] In one instance, a twin-engine aircraft was carried 2.4 km (1.5 mi) from the hangar it was tied down in. A metal sign bolted into a warehouse was tossed 3.7 km (2.3 mi) and found half-buried in the ground.[12] Elsewhere, a quonset hut was lofted and carried for 125 m (411 ft), intact, before being crushed on impact.[4] Along the coast, the USS Arco was torn from her moorings, severing two anchors and shearing a cleat – tested for over 23,000 and 45,000 kg (50,000 and 100,000 lb), respectively – in the process.[4][12] The ROK Han Ra San and RPS Negros Oriental sank in the inner harbor of Guam.[14]

Karen is regarded as the worst typhoon to ever impact Guam. Acting governor Manuel Guerrero stated that "the entire territory was devastated." Almost all structures, both civilian and military, were severely damaged or destroyed.[9] Even reinforced concrete structures at Anderson Air Force Base sustained severe damage.[15] Though these structures withstood the direct impact of winds, sudden drops in pressure caused windows to shatter in most structures, ultimately exposing the interior to water damage. Military structures suffered the most from this phenomenon as the buildings were designed in a way that pressure differences between the interior and exterior would not equal out. Debris from damaged or destroyed homes became projectiles during the storm that created further damage, like "shrapnel or artillery missiles."[12]

George Washington High and Tumon Junior High were both destroyed. Guam Memorial Hospital and the island's public works department were extensively damaged.[9] Downtown Hagåtña, Guam's largest city, was flattened.[16] Along the city's main road, Marine Drive, 20 cm (8 in) of sand accumulated from Karen's storm surge.[8] Overall, the city was 85 percent destroyed, while the villages of Yona and Inarajan were 97 and 90 percent destroyed, respectively.[17] Additionally, Agana Heights and Sinajana were reportedly leveled.[8] The communication network on the island was completely destroyed as antennas and transmission equipment were blown away.[9] Approximately 30 percent of telephone poles between the island's naval station and Nimitz Hill and 95 percent of civilian telephone poles were downed.[18] The power grid was also destroyed.[19] The Guam portion of the Pacific Scatter Communications System suffered extensive damage, with all four 61 m (200 ft) antennas at Ritidian Point being reduced to a "mess of tangled, twisted steel and cable." Losses from the antennas alone reached $1 million.[20] All airstrips on the island were rendered inoperable, hampering initial relief efforts.[21] Numerous roads across the island were also impassable, covered by downed trees and smashed vehicles.[16] The wreckage left in the wake of the storm was described as a "massive junkyard".[22]

Throughout Guam, 95 percent of homes were destroyed,[1] and those left standing were damaged.[16] Nearly every non-typhoon-proof home was severely damaged or destroyed and a majority of typhoon-proof buildings sustained extensive damage.[7] Preliminary surveys by the Red Cross on November 15 indicated that at least 5,000 homes were destroyed and another 3,000 were severely damaged.[23] Approximately 45,000 people, mostly Guamanians, were left homeless.[19] A total of 11 people lost their lives and about 100 others were injured.[1][2] At least four of the deaths were due to collapsed buildings, including three in one home that buckled due to pounding surf.[8] Another death resulted from decapitation by airborne debris.[4] Losses across the island amounted to $250 million (1962 USD).[1][2] The damage across Guam was described as "'much more serious" than it had been during the second Battle of Guam, when American troops retook the island from the Japanese.[24] The U.S. Navy described the damage as equal to that of an indirect hit from a nuclear bomb.[25] Guerrero said that the recovery effort of the previous 17 years had been "completely wiped out".[26]

Elsewhere

In the Mariana Islands, three ships under the command of Rear Admiral J. S. Coye Jr. sank; however, the crew had been evacuated prior to the storm's arrival.[13]

On November 13, a level three TCOR was issued for Okinawa. This prompted military personnel to begin securing the island and preparing planes without hangars for evacuation.[27] Brushing the region as a Category 3-equivalent typhoon,[3] Karen caused considerable disruptions to airlines, trains, shipping, and communications.[28] No serious damage was reported in Okinawa,[29] but the nearby Daiyumaru and another Japanese fishing vessel with a total of 26 crew went missing.[19][30]

On November 15, residents in Taiwan were urged to take precautions to minimize casualties.[31] Prior to the storm's arrival, the USS Duncan, the USS Kitty Hawk, and two other aircraft carriers sought refuge in the Taiwan Strait. Despite attempts to escape the storm, large swells exceeding 3.6 m (12 ft) battered the vessels, causing them to pitch up to 59 degrees. At times, the waves crashed onto the deck of the USS Kitty Hawk. According to crewmen, waves up to 4.5 m (15 ft) struck Taipei, leaving water marks on many buildings.[32]

Aftermath

"I'm sure you shared with me the disturbing feeling during the past two days that we were alone, friendless and beyond assistance from outside."

Acting Governor Manuel Guerrero[7]

In the immediate aftermath of the typhoon, the Pacific Air Forces were on standby to deliver supplies to Guam, but were delayed by inoperable airstrips. Guam Memorial Hospital was damaged, but other civilian and military installations, including the Navy's hospital, were able to handle injured persons.[16][18] On November 12, Manuel Guerrero made an urgent appeal to the Government of the United States requesting that aid be rushed to the territory.[9] Additionally, he instituted an island-wide curfew between 8:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m. local time to limit looting. At schools, teachers were called in to guard supplies and equipment.[19] The Federal Emergency Management Agency, under orders from United States President John F. Kennedy, declared Guam a major disaster area later that day, allowing residents to receive federal aid.[24][33] Additionally, 15 United States Air Force communications technicians were deployed from Manila, Philippines carrying three plane-loads of communication supplies.[19] Guerrero estimated that it would take four months to complete repairs to utilities.[15] It was also estimated that schools on the island would be closed for six months.[34]

Initially, residents across Guam were critical of the delayed response by the U.S. government; no aid had arrived within two days of the storm, but unsafe conditions at airports had prevented aircraft from landing.[7] With the majority of homes destroyed across Guam, structures that remained standing were used as temporary shelter for those left homeless.[19] Similarly, damaged military installations at Anderson Air Force Base were made available to all civilians.[16] By November 14, the USS Daniel I. Sultan arrived in Guam with 1,100 troops to provide emergency power.[13] A U.S. Air Force AC-130 landed on the island that day carrying the first package of relief supplies. About 400 troops and 80 public works employees were sent from Hawaii on November 14.[7] The Red Cross and civil defense offices were placed in charge of coordinating recovery efforts. Water distribution centers were set up across the island to provide residents with clean drinking water.[22]

On November 15, a massive evacuation of residents began to remove survivors from unsafe conditions. Two flights to California took place on the first day of evacuation, carrying a total of 154 people. Thousands of residents were also brought to Wake Island for shelter. Military Air Transport Service planes from the United States mainland, Japan, the Philippines, and Hawaii were called in for the operation.[35] On November 16, residents were warned of a possible typhoid epidemic and urged to get inoculations for the disease.[29] Over a three-day span, roughly 30,000 people were given preventative shots for the disease.[36] In contrast to their previous ban on alien workers, the Government of Guam requested 1,500 carpenters, masons, and other building workers from the Philippines.[29] By November 21, the Navy Supply Depot planned to have enough supplies for the entire populous shipped until replenishment arrived.[35] In order to shelter homeless, the United States Navy set up tent villages across the island. Military kitchens were also established to provide food. Due to continued rains in the wake of the typhoon, many were unable to get a full meal for Thanksgiving.[37]

On November 21, insurance payments for losses were expected to exceed $12 million.[37] On January 1, 1963, a $2 million relief fund was authorized by President Kennedy.[38] Another $5.4 million in relief funds were provided by President Lyndon B. Johnson on February 15, 1964.[39] The United States Congress provided Guam with $60 million, including $45 million through federal loans, mainly to help rebuild the territory and promote expansion of the economy. Additionally, the storm brought about the end of military security on the island, which in turn aided economic growth. Within five years of this decision, Japanese tourism to the island dramatically increased, prompting a major increase in the number of hotels.[40] In the long term, Typhoon Karen, along with other destructive storms, shaped the development of the island's infrastructure. It led to higher quality buildings and more efficient utilities that could withstand powerful typhoons.[41] Since Karen, most buildings on the island have been constructed with concrete and steel.[42]

On April 29, 1963, less than half a year after Karen, Typhoon Olive caused extensive damage in Guam and the Mariana Islands.[43] With many residents living in tents, and debris from the storm still scattered about, severe damage was anticipated. Schools, churches, and other structures were opened as shelters in order to protect those without homes.[44] Ultimately, Guam was spared the worst of the storm though much of Saipan was devastated.[43] The island was again devastated in 1976 by Typhoon Pamela which buffeted the island with destructive winds for 36 hours. Though weaker than Karen, the longer lasting impact of Pamela was regarded as more destructive.[45]

Due to the severity of damage caused by the typhoon in Guam, the name Karen was retired and replaced with Kim.[46][47]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Typhoon Karen. |

- 1962 Pacific typhoon season

- Other notable typhoons in Guam

Notes

- ↑ All damage totals are in 1962 values.

References

- General

- Lawrence J. Cunningham & Janice J. Beaty (2001). A History of Guam. Bess Press. ISBN 1-57306-068-2.

- Specific

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 John A. Rupp & Mark A. Lander (May 1996). "A Technique for Estimating Recurrence Intervals of Tropical Cyclone-Related High Winds in the Tropics: Results for Guam" (PDF). Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology. Joint Typhoon Warning Center and University of Guam. 35 (5): 627–637. Bibcode:1996JApMe..35..627R. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1996)035<0627:ATFERI>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: Typhoon Karen" (PDF). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. United States Navy. 1963. pp. 202–216. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "1962 Karen (1962311N06154)". International Best Track Archive. 2013. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Letters to the Editor". Mariner's Weather Log. Washington, D.C.: United States Weather Bureau. 7 (2): 52–55. March 1963.

- ↑ Neal Dorst, Hurricane Research Division, and Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (January 27, 2010). "Subject: E8) What hurricanes have been at Category Five status the longest?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Questions:. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ Digital Typhoon (2013). "Typhoon 196228 (Karen) - Detailed Track Information". Japan Meteorological Agency. National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 United Press International (November 14, 1962). "After Karen Hits.... U.S. Rushes Aid To Guam". The Bonham Daily Favorite. Agana, Guam. p. 2. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Crossroads: Karen Shatters Guam In Direct Hit". Airborne Early Warning Squadron One. November 30, 1962. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Associated Press (November 12, 1962). "Guam Starts Digging Out: Typhoon Karen Batters Island". Eugene Register-Guard. Honolulu, Hawaii. p. 1. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (November 12, 1962). "Typhoon Karen Strikes Guam; Reports Vague". St. Petersburg Times. Honolulu, Hawaii. p. 6A. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (November 12, 1962). "Typhoon Rips Guam To Shreds: $100 Million damage; Hundreds Injured; One Dead". The Miami News. Honolulu, Hawaii. p. 1. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Crossroads: Fleet Weather Central Reviews Catastrophic Karen". Fleet Weather Central, Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Airborne Early Warning Squadron One. November 30, 1962. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- 1 2 3 United Press International (November 14, 1962). "After Typhoon Karen: Guam Curfew Ordered To Prevent Looting". St. Petersburg Times. Agana, Guam. p. 2A. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ "PC-485". NavySource. 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- 1 2 Associated Press (November 13, 1962). "Guam Clears Debris Left By Typhoon". Meriden Record. Agana, Guam. p. 14. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Associated Press (November 13, 1962). "Six Dead In Guam Typhoon: Damage by Karen Set at Hundreds Of Millions". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Honolulu, Hawaii. pp. 1, 20. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ Edward Neilan (Copley News Service) (December 12, 1962). "Typhoon Karen". Lodi News-Sentinel. Hong Kong. p. 6. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- 1 2 Associated Press (November 12, 1962). "Guam Hit By 'Worst': Big Blow Paralyzes Hub of Pacific Defense Ring; U.S. Aid Requested". Reading Eagle. Honolulu, Hawaii. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Associated Press (November 13, 1962). "Typhoon Karen Wreaks Dreadful Guam Toll". The Windsor-Star. Honolulu, Hawaii. p. 2. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Crossroads: NCS Rides Out Karen; Antenna Farms 'A Mess'". Airborne Early Warning Squadron One. November 30, 1962. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (November 12, 1962). "Typhoon Hits Guam, Damages Run Heavy". Ocala Star-Banner. Honolulu, Hawaii. p. 1. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- 1 2 Associated Press (November 14, 1962). "Typhoon Toll Likely To Rise". Kentucky New Era. Agana, Guam. p. 5. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (November 15, 1962). "Refugees From Guam Land In U.S.". The Evening Independent. Travis Air Force Base, California. p. 2A. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- 1 2 Associated Press (November 13, 1962). "Typhoon Slams Guam Harder Than War". The Miami News. Honolulu, Hawaii. p. 3A. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ Cunningham, p.301

- ↑ Australian Associated Press (November 14, 1962). "Typhoon Toll Six Dead". The Age. Honolulu, Hawaii. p. 4. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (November 13, 1962). "Okinawa Braces For Typhoon". St. Joseph News-Press. Naha, Okinawa. p. 5. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Typhoon Hits Japanese Islands". Tokyo, Japan: The Miami News. November 16, 1962. p. 1. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- 1 2 3 United Press International (November 16, 1962). "Typhoon Heads for Japan; Guam Fights Fever Threat". Eugene Register Guard. Agana, Guam. p. 2A. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (November 19, 1962). "Old Devil Sea Is Acting Up". The Robesonian. p. 1. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ Robert Myers (Associated Press) (November 15, 1962). "Picking Up the Pieces: Cooperation Is Key to Guam Recovery". The Day. Agana, Guam. p. 1. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ "USS Duncan (DDR - 874): Memories of Typhoon Karen". USS Duncan DDR 874 Crew & Reunion Association. July 27, 1997. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Guam Typhoon Karen (DR-140)". Federal Emergency Management Agency. United States Government. November 12, 1962. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (November 16, 1962). "Aftermath of the Guam Typhoon". The Age. p. 5. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- 1 2 Associated Press (November 15, 1962). "Big Airlift Speeding Evacuees Homeward". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Honolulu, Hawaii. p. 1. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Crossroads: NavHosp Shelters, Aids, Treats Typhoon Victims". Airborne Early Warning Squadron One. November 30, 1962. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- 1 2 Edwin Engledow (Associated Press (November 21, 1962). "Storm-Torn Guam Has Saddest Thanksgiving". Lakeland Ledger. Agana, Guam. p. 5. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (January 1, 1963). "JFK Prepares To Celebrate The New Year". St. Petersburg Times. Palm Beach, Florida. p. 2A. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Guam Gets More Disaster Aid". The New York Times. February 15, 1964. (subscription required)

- ↑ Larry W. Mayo (July 1988). "U.S. Administration and Prospects for Economic Self-Sufficiency: A Comparison of Guam and Select Areas of Micronesia" (PDF). Pacific Studies. Salisbury State College. 11 (3): 53–75. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ Tony P Sanchez (December 23, 2002). "Mother Nature always helps Guam chart new directions". Pacific Daily News. Hagatna, Guam. p. A28. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ David J. Sablan (2012). "Message from the Chairman". Guam Housing and Urban Renewal Authority. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- 1 2 Associated Press (April 29, 1963). "Typhoon Flatten Saipan!". The Evening Independent. Agana, Guam. p. 3A. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ Associated Press (April 29, 1963). "Island Put On Alert In Pacific". St. Petersburg Times. Agana, Guam. p. 1. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ United Press International (May 24, 1976). "Guam in ruins after 'Pamela'". Star-News. Agana, Guam. p. 3A. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ Gary Padgett, Jack Beven, James Lewis Free, Sandy Delgado, Hurricane Research Division, and Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (May 23, 2012). "Subject: B3) What storm names have been retired?". Tropical Cyclone Frequently Asked Questions:. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ↑ Xiaotu Lei and Xiao Zhou (Shanghai Typhoon Institute of China Meteorological Administration) (February 2012). "Summary of Retired Typhoons in the Western North Pacific Ocean". Tropical Cyclone Research and Review. 1 (1): 23–32. doi:10.6057/2012TCRR01.03 (inactive 2015-02-01). Retrieved April 21, 2013.