Urinary catheterization

| Urinary catheterization | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

Urinary catheterization with a dummy | |

| ICD-9-CM | 57.94 |

| MeSH | D014546 |

| MedlinePlus | 003981 |

In urinary catheterization a latex, polyurethane, or silicone tube known as a urinary catheter is inserted into a patient's bladder via the urethra. Catheterization allows the patient's urine to drain freely from the bladder for collection. It may be used to inject liquids used for treatment or diagnosis of bladder conditions. A clinician, often a nurse, usually performs the procedure, but self-catheterization is also possible. The catheter may be a permanent one (indwelling catheter), or an intermittent catheter removed after each catheterization.

Catheter types

Catheters come in several basic designs:[1]

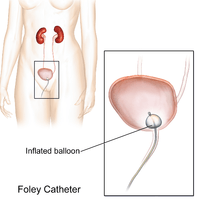

- A Foley catheter (indwelling urinary catheter) is retained by means of a balloon at the tip that is inflated with sterile water. The balloons typically come in two different sizes: 5 cm3 and 30 cm3. They are commonly made in silicone rubber or natural rubber.

- An intermittent catheter/Robinson catheter is a flexible catheter used for short term drainage of urine. Unlike the Foley catheter, it has no balloon on its tip and therefore cannot stay in place unaided. These can be non-coated or coated (e.g., hydrophilic coated and ready to use).

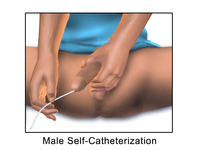

- Intermittent self catheterization in males is best performed with a flexible catheter to drain the bladder periodically. The procedure should not be attempted by a patient without guidance in maintaining cleanliness of the catheter and surrounding area and specific instruction regarding catheter insertion from meatus to bladder entry.

- A coudé catheter is designed with a curved tip that makes it easier to pass through the curvature of the prostatic urethra.

- A hematuria (or haematuria) catheter is a type of Foley catheter used for Post-TURP hemostasis. This is useful following endoscopic surgical procedures, or in the case of gross hematuria. There are both two-way and three-way hematuria catheters (double and triple lumen).[1]

- An external, Texas, urisheat, or condom catheter is used for incontinent males and carries a lower risk of infection than an indwelling catheter.[2]

Catheter diameters are sized by the French catheter scale (F). The most common sizes are 10 F (3.3mm) to 28 F (9.3mm). The clinician selects a size large enough to allow free flow of urine, and large enough to control leakage of urine around the catheter. A larger size is necessary when the urine is thick, bloody, or contains large amounts of sediment. Larger catheters, however, are more likely to damage the urethra. Some people develop allergies or sensitivities to latex after long-term latex catheter use making it necessary to use silicone or Teflon types.

Evidence does not support an important decrease in the risk of urinary tract infections when silver-alloy catheters are used.[3]

Sex differences

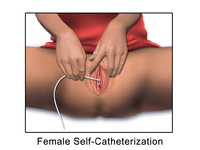

In males, the catheter tube is inserted into the urinary tract through the penis. A condom-type catheter (also known as a 'Texas catheter'), if used, fits around the tip of the penis, rather than being inserted. In females, the catheter is inserted into the urethral meatus, after a cleansing using povidone-iodine. The procedure can be complicated in females due to varying layouts of the genitalia (due to age, obesity, female genital cutting, childbirth, or other factors), but a good clinician would rely on anatomical landmarks and patience when dealing with such a patient. In the UK it is generally accepted that cleaning the area surrounding the urethral meatus with 0.9% sodium chloride solution is sufficient for both male and female patients as there is no reliable evidence to suggest that the use of antiseptic agents reduces the risk of urinary tract infection.[4]

Males may have a slightly higher incidence of bladder spasms. If bladder spasms occur, or there is no urine in the drainage bag, the catheter may be blocked by blood, thick sediment, or a kink in the catheter or drainage tubing. Sometimes spasms are caused by the catheter irritating the bladder, prostate, or penis. Such spasms can be controlled with medication such as butylscopolamine, although most patients eventually adjust to the irritation and the spasms go away.[5]

Common indications to catheterize a patient include acute or chronic urinary retention (which can damage the kidneys), orthopedic procedures that may limit a patient's movement, the need for accurate monitoring of input and output (such as in an ICU), benign prostatic hyperplasia, incontinence, and the effects of various surgical interventions involving the bladder and prostate.

For some patients the insertion and removal of a catheter causes excruciating pain, so a topical anesthetic is used. Catheterization would be performed as a sterile medical procedure by trained, qualified personnel, using equipment designed for this purpose, except in the case of intermittent self-catheterization where patients have been trained to perform the procedure themselves.

Intermittent self-catheterization is performed by the patient four to six times a day, using a clean technique in most cases. Nurses use a sterile technique to perform intermittent catheterization in hospital settings. Incorrect technique may cause trauma to the urethra or prostate (male), urinary tract infection, or a paraphimosis in the uncircumcised male. For patients with spinal cord lesions and neurogenic bladder dysfunction, intermittent catheterisation (IC) is a standard method for bladder emptying. The technique is safe and effective and results in improved kidney and upper urinary tract status, lessening of vesicoureteral reflux and amelioration of continence.[6] In addition to the clinical benefits, patient quality of life is enhanced by the increased independence and security offered by self-catheterization.[7][8]

| Illustrations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

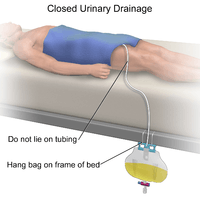

Catheter maintenance

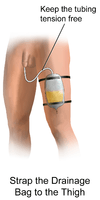

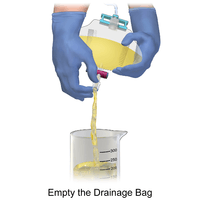

A catheter that is left in place for more than a short period of time is generally attached to a drainage bag to collect the urine. This also allows for measurement of urine volume. There are three types of drainage bags: The first is a leg bag, a smaller drainage device that attaches by elastic bands to the leg. A leg bag is usually worn during the day, as it fits discreetly under pants or skirts, and is easily emptied into a toilet. The second type of drainage bag is a larger device called a down drain that may be used overnight. This device is hung on a hook under the patient's bed—never placed on the floor, due to risk of bacterial infection. The third is called a belly bag, and is secured around the waist. This bag can be worn at all times. It can be worn under the patient's underwear to provide a totally undetectable look.

During long-term use, the catheter may be left in place all the time, or a patient may be instructed on a procedure for placing a catheter just long enough to empty the bladder and then removing it (known as intermittent self-catheterization). Patients undergoing major surgery are often catheterized and may remain so for some time. The patient may require irrigation of the bladder with sterile saline injected through the catheter to flush out clots or other matter that does not drain.[9]

| Maintenance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Effects of long term use

The duration of catheterization can have significance for the patient. Incontinent patients commonly are catheterized to reduce their cost of care. However, long-term catheterization carries a significant risk of urinary tract infection. Because of this risk catheterization is a last resort for the management of incontinence where other measures have proved unsuccessful. Other long term complications may include blood infections (sepsis), urethral injury, skin breakdown, bladder stones, and blood in the urine (hematuria). After many years of catheter use, bladder cancer may also develop.

Preventing infection

Everyday care of catheter and drainage bag is important to reduce the risk of infection.[10] Such precautions include:

- Cleansing the urethral area (area where catheter exits body) and the catheter itself.

- Disconnecting drainage bag from catheter only with clean hands

- Disconnecting drainage bag as seldom as possible.

- Keeping drainage bag connector as clean as possible and cleansing the drainage bag periodically.

- Use of a thin catheter where possible to reduce risk of harming the urethra during insertion.

- Drinking sufficient liquid to produce at least two liters of urine daily

- Sexual activity is very high risk for urinary infections, especially for catheterized women.

There is no clear evidence that any one catheter type or insertion technique is superior than another in preventing infection.[11]

Recent developments in the field of the temporary prostatic stent have been viewed as a possible alternative to indwelling catheterization and the infections associated with their use.[12]

References

- 1 2 Hanno, Philip M.; Wein, Alan J.; Malkowicz, S. Bruce. (2001). Clinical manual of urology.. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 78.

- ↑ Black, Mary Ann (1994). Medical nursing (2nd ed.). Springhouse, Pa.: Springhouse Corp. p. 97. ISBN 0-87434-738-6. LCCN 94035389.

- ↑ Lam, TB; Omar, MI; Fisher, E; Gillies, K; MacLennan, S (Sep 23, 2014). "Types of indwelling urethral catheters for short-term catheterisation in hospitalised adults.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 9: CD004013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004013.pub4. PMID 25248140.

- ↑ Royal Marsden Handbook of Clinical Nursing Procedure 6th ed., London.

- ↑ "Urinary catheters". MedlinePlus, the National Institutes of Health's Web site. 2010-03-09. Retrieved 2010-12-01.

- ↑ Hedlund, H.; Hjelmås, K.; Jonsson, O.; Klarskov, P.; Talja, M. (Feb 2001). "Hydrophilic versus non-coated catheters for intermittent catheterization.". Scand J Urol Nephrol. 35 (1): 49–53. doi:10.1080/00365590151030822. PMID 11291688.

- ↑ Lapides, J.; Diokno, AC.; Silber, SJ.; Lowe, BS. (Mar 1972). "Clean, intermittent self-catheterization in the treatment of urinary tract disease.". J Urol. 107 (3): 458–61. PMID 5010715.

- ↑ Winder, A. (Nov–Dec 2002). "Intermittent self-catheterisation.". Nurs Times. 98 (48): 50. PMID 12501532.

- ↑ Best practices : evidence-based nursing procedures (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2007. ISBN 978-1-58255-532-4. LCCN 2006012245.

- ↑ "Care for your catheter". Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- ↑ Prieto, J; Murphy, CL; Moore, KN; Fader, M (Sep 10, 2014). "Intermittent catheterisation for long-term bladder management.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 9: CD006008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006008.pub3. PMID 25208303.

- ↑ Neal D. Shorea, Martin K. Dineenb, ‡, Mark J. Saslawskyc, §, Jeffrey H. Lumermand and Alberto P. Corica (March 2007). "A Temporary Intraurethral Prostatic Stent Relieves Prostatic Obstruction Following Transurethral Microwave Thermotherapy". The Journal of Urology. 177 (3): 1040–6. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.059. PMID 17296408.