1960 in the Vietnam War

| 1960 in the Vietnam War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

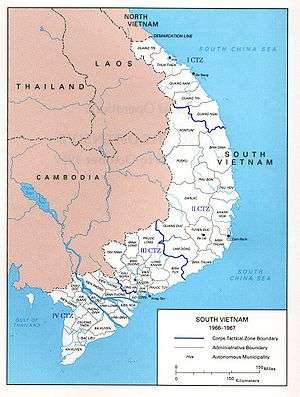

A map of South Vietnam showing provincial boundaries and names and military zones (1, II, III, and IV Corps). | |||

| |||

| Belligerents | |||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||

| Strength | |||

| US: 900[1] | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

|

US: 5 killed South Vietnam: 2,223 killed | North Vietnam: casualties | ||

In 1960, the oft-expressed optimism of the United States and the Government of South Vietnam that the Viet Cong were nearly defeated proved mistaken. Instead the Viet Cong became a growing threat and security forces attempted to cope with Viet Cong attacks, assassinations of local officials, and efforts to control villages and rural areas. Throughout the year, the U.S. struggled with the reality that much of the training it had provided to the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) during the previous five years had not been relevant to combating an insurgency. The U.S. changed its policy to allow the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) to begin providing anti-guerrilla training to ARVN and the paramilitary Civil Guard.

President Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam was faced with growing dissatisfaction with his government culminating in a coup d'état attempt by military officers in November.

North Vietnam's support for the Viet Cong increased and in December the National Liberation Front (NLF) was created to carry on the struggle. Ostensibly a coalition of anti-Diem organizations, the NLF was largely under the control of North Vietnam's communist party.

January

- 4 January

President Diem said to General Samuel Williams, the head of the MAAG in Saigon, that the counterinsurgency programs of his government had been successful and that "the Communists have now given up hope of controlling the countryside."[2]

- 7 January

General Williams said that "the internal security situation here now, although at times delicate, is better than it has been at any time in the last two or three years.[3]

- 17 January – 26 February

In what has been called "the start of the Vietnam War", the Viet Cong attacked and took temporary control of several districts in Kiến Hòa Province (now Bến Tre Province) in the Mekong Delta.[4] The Viet Cong set up "people's committees," and confiscated land from landlords and redistributed it to poor farmers. One of the leaders of the uprising was Madame Nguyễn Thị Định who led the all-female "Long Hair Army." Dinh was the secretary of the Bến Tre Communist Party and later a Viet Cong Major General.[5]

Although the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) recaptured the villages, uprisings spread to many other areas of South Vietnam. The uprisings were spontaneous rather than reflecting the official policy of the Communist government in Hanoi which was that the Viet Cong's stance should be restrained and defensive, not offensive.[6]

- 26 January

Two hundred Viet Cong guerrillas attacked the headquarters of the South Vietnamese 32nd regiment in Trang Sup village in Tây Ninh Province northeast of Saigon. The Viet Cong killed or wounded 66 soldiers and captured more than 500 weapons and a large quantity of ammunition. Later, a Viet Cong spokesman said that "the purpose of the attack was to launch the new phase of the conflict with a resounding victory and to show that the military defeat [of the South Vietnamese Army] was easy, not difficult." The attack shocked the Diệm government and its American advisers. An Embassy study group of the implications of the battle recommended that two divisions of the ARVN be trained in guerrilla warfare.[7]

February

- 15 February

On his own initiative without consulting his American advisers, President Diem ordered the formation of commando companies to undertake counter-insurgency (as anti-guerrilla warfare was beginning to be called) operations. Diem planned to create 50 commando companies, composed of volunteers, of 131 men each. MAAG and the U.S. Department of Defense opposed Diem's proposal. General Williams said that Diem's proposal to create 50 commando companies was "hasty, ill-considered, and destructive." To defeat the Viet Cong, he said that South Vietnam needed a well-trained Civil Guard, intensive training between operations, improved counterintelligence, and a clear chain of command. Another concern of the U.S. was the Diem's proposal was an attempt to increase the number of South Vietnamese military personnel beyond the 150,000 ceiling that the U.S. was committed to support.[8]

- 19 February

American Ambassador Elbridge Durbrow requested that U.S. Army Special Forces provide anti-guerrilla training to the 50,000 man para-military Civil Guard of Vietnam. CIA Operative Colonel Edward Lansdale in Washington concurred with the request. Up until this time the MAAG in South Vietnam had provided training only for conventional warfare and only to the South Vietnamese Army.[9]

- 26 February

President Diem requested that the United States provide anti-guerrilla training to both the Civil Guard and ARVN.[9]

March

- 2 March

Ambassador Durbrow reported to the Department of State that the Viet Cong now numbered more than 3,000 men and that the Diem government was losing its capability of dealing with the Viet Cong insurgency in rural areas.[10]

Two hundred Viet Cong in the Mekong Delta ambushed three ARVN companies. More than 40 soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing.[11]

- 18 March

Stimulated by a report from CIA operative and Diem confidant Edward Lansdale, a military conference in Washington concluded that in South Vietnam "military operations without a sound political bases will be only a temporary solution." The conference recommended that the U.S. assign advisers to Vietnamese provincial governments to attempt to overcome shortcomings of the government at the local as well as the national level. The recommendation had little immediate impact.[12]

- 20 March

General Williams, head of MAAG in Saigon, reported a difficult military situation in the Mekong Delta region of South Vietnam. The Viet Cong were overrunning Civil Guard (rural para-military) posts and assassinating village officials. The guerrillas were also launching successful attacks on the South Vietnamese army. ARVN was unable to deal effectively with the guerrillas.[13]

- 25 March

An ARVN company on the Cai Nuoc River in the Mekong Delta was ambushed by Viet Cong. More than 50 ARVN soldiers were killed or wounded. A few days later in the same area more than 100 ARVN soldiers were killed in an ambush.[14]

- 30 March

In response to the request of Ambassador Durbrow, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff reversed MAAG policy and directed that MAAG assist the ARVN to develop an anti-guerrilla capability.[9]

April

- 7 April

Ambassador Durbrow requested permission from the State Department to threaten Diem with actions to encourage him to reform his government. General Williams in Saigon and General Lansdale in Washington, strongly disagreed with Durbrow. Lansdale said "it would not be wisdom now, at a time of threat, to harass Diem with ill-conceived political innovations.[15]

- 14 April

Increasing evidence was coming to light that the Viet Cong had infiltrated many South Vietnamese government agencies including the army. The CIA reported that the South Vietnamese army had conducted five major operations in the Mekong Delta that year. In each case, 'there was every evidence that the Viet Cong knew in advance" about the date, plan, and route of the operation.[16]

- 15 April

Communist authorities in Hanoi continued to resist supporting an all-out insurgency in South Vietnam. National Assembly leader Tôn Đức Thắng said "the will and keen wish of our [North Vietnamese] people are work and peace. We want to preserve peace in order for our people to use their strength to build socialism." However, at the same meeting of the National Assembly southern leaders called for assistance and support from the north to support the Viet Cong who faced "an extremely unsafe situation."[17]

- 17 April

North Vietnam protested to Great Britain and the Soviet Union, co-chairmen of the 1954 Geneva Convention, about the large increase in the U.S. military presence in South Vietnam and accused the U.S. of preparing for "a new war."[18]

- 18 April

The South Vietnamese army reported that it had killed 931 Viet Cong and captured 1,300 from mid-January to mid-April, but reported that they had captured only 150 weapons. During the same period the ARVN lost more than 1,000 weapons which led General Williams to doubt "how a well-trained...soldier feels it necessary to throw his weapons away."[19]

- 23 April

The Army Times praised General William's MAAG group in Saigon as possibly "the finest there is."[20]

- 27 April

Eighteen prominent Vietnamese intellectuals, the "Caravelle Group",” wrote to President Diem to express their concerns about the direction the government was taking. In particular they protested against the agroville program which aimed to concentrate rural residents into protected settlements. The intellectuals said, “Tens of thousands of people are being mobilized for hardship and toil to leave their work and go far from their homes and fields, separated from their parents, wives and children, to take up a life in collectivity in order to construct beautiful but useless agro-villes which tire the people, lose their affection, increase their resentment and most of all give an additional opportunity for propaganda to the enemy.”[21]

May

Three U.S. Special Forces teams, a total of 46 soldiers, arrived in Vietnam to train Vietnamese commando companies. These 4-week courses were the first formal training for counterinsurgency operations that the U.S. had provided to the ARVN.[22]

- 5 May

The U.S. announced that the number of personnel of the MAAG will be increased from 327 to 685 by the end of 1960.[23]

- 9 May

President Eisenhower agreed that Diem was becoming "arbitrary and blind" to the growing problems of his country and directed the State Department, CIA, and the DOD to try to prevent the further deterioration of the situation."[24]

- 20 May

General Williams told Senator Mike Mansfield that MAAG could probably be reduced in size in 1961 by about 15 percent and reduced another 20 percent in 1962.[11]

June

- 2 June

In an interview with Time-Life magazines General Williams said that the South Vietnamese army was "whipping" the Viet Cong.[25]

- 3 June

A senior South Vietnamese official told the CIA that the government would probably lose control to the Viet Cong of the Cà Mau Peninsula, the southernmost part of South Vietnam.[26]

- 6 June

The U.S. Embassy in Saigon submitted a critical analysis of the Agroville Program to the Department of State. The program, begun by President Diem, aimed to concentrate rural villagers into defensible settlements. The Embassy stated that the Agroville program "is a complete reversal of tradition and the social and economic pattern of the people affected. It is apparent that all planning and decisions have been made without their participation and with little if any consideration of their wishes, interests or views." Diem abandoned the unpopular program in August.[27]

July

The Nam Bo (Southern Vietnam) Executive Committee of the Viet Cong asked Hanoi for more and better weapons as the armed struggle against the Diem government was still weak.[28]

August

- 9 August

Captain Kong Le and the 2nd Lao Paratroop battalion overthrew the government of Laos, thus initiating a struggle for power in Laos with both the United States and the Soviet Union taking sides and supporting their respective factions. For the remainder of 1960 and extending into 1961, Laos eclipsed Vietnam in the interest of the superpowers and the media.[9]

- 23 August

The U.S. government compiled a National Intelligence Estimate stating that support for the Viet Cong was increasing and that supplies and combatants were moving to them from North Vietnam overland and by sea. The Diem government faced growing hostility. "Criticism...focuses on Ngo family rule, especially the role of the President's brother Ngo Dinh Nhu and Madam Nhu, the pervasive influence of the Can Lao...[and if] these adverse trends....remain unchecked, they will almost certainly in time cause the collapse of Diem's regime."[29]

- 29 August

The British Embassy reported to London that Ho Chi Minh, Võ Nguyên Giáp and other moderates were being criticized by more militant communist party members for the lack of progress toward reunification of South and North Vietnam. Party militants were arguing for a more aggressive policy. For the moment, the British believed that the moderates had the upper hand.[30]

September

- 1 September

General Lionel C. McGarr replaced General Williams as chief of MAAG in Saigon. Williams had been in the position since 1955.[9]

- 7 September

At the Third National Party Congress in Hanoi, North Vietnam approved a 5-year economic plan with the goal of becoming a socialist economy by 1965, replacing private enterprise with state capitalism, and promoting industrialization. This despite a reduced rice ration for the population and discontent in rural areas and the cities, especially among intellectuals, shopkeepers, and Catholics.[31]

- 13 September

General Lansdale, now Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, argued that Diem was the only option for stability in South Vietnam and that he should be assured "of our intent to provide material assistance and of our unwavering support to him in this time of crisis."[32]

- 16 September

Ambassador Durbrow told the U.S. Department of State that the Diem government was facing two threats: a coup supported by non-communist opponents in Saigon and the expanding Viet Cong threat in rural areas. "Political, psychological and economic measures" in addition to military and security measures would be necessary to meet the threats.[33]

- 22 September

The CIA said that Vietnamese army reports to Saigon from the provinces were doctored "to make it appear that they [the ARVN] wee continually conducting successful anti-communist operations. In one province, ARVN reported it had captured 60 Viet Cong, but an investigation discovered that all 60 were civilians.[19]

- 26 September

The Third National party Congress of the communist party in Hanoi reaffirmed the priority of strengthening the economy and government in North Vietnam rather than assisting the insurgency in South Vietnam. The Viet Cong would have to continue the struggle against South Vietnam utilizing mostly their own resources. However, the Congress elected Lê Duẩn as First Secretary of the Communist Party over Võ Nguyên Giáp. Giap was a moderate while Le Duan was a militant who had advocated more aggressive action by the North to aid the Viet Cong. His election may have been a concession to the southerners who were displeased with the lack of support from the Congress for their cause.[34]

October

- 14 October

Ambassador Durbrow met with President Diem and requested that Diem take a number of actions to "broaden and increase his popular support."

- 26 October

In a letter President Eisenhower congratulated President Diem on the fifth anniversary of South Vietnam's creation. Eisenhower said that "the United States will continue to assist Vietnam in the difficult yet hopeful struggle ahead."[23]

November

- 8 November

The United States presidential election of 1960 marked the end of Dwight D. Eisenhower's two terms as President. Eisenhower's Vice President, Richard Nixon, who had transformed his office into a national political base, was the Republican candidate, whereas the Democrats nominated Massachusetts Senator John F. Kennedy. Kennedy won on November 8, 1960.

- 8 November

For the first time South Vietnam charged North Vietnam with aggression. A few days earlier the Viet Cong had captured several ARVN and Civil Guard posts near Kontum in the central highlands. The Diem government claimed that the attack had been mounted by soldiers from North Vietnam who had infiltrated South Vietnam through Laos utilizing the network of trails and roads later called the Ho Chi Minh trail. The ARVN recaptured the lost posts.[35]

- 11 November

Five paratroop battalions encircled the Presidential Palace in Saigon in what would be a failed coup attempt against President Diem. The coup attempt was led by Lieutenant Colonel Vương Văn Đông and Colonel Nguyễn Chánh Thi of the Airborne Division. Diem negotiated with Colonel Dong, promising reforms, until loyal forces could be gathered to put down the rebels.

- 12 November

Two infantry divisions loyal to Diem arrived at the Presidential Palace, engaged the rebels and forced them to withdraw. The coup attempt had failed. The leaders fled to Cambodia where they were given sanctuary by Prince Norodom Sihanouk.[36]

- 13 November

The New York Times said that Diem was "between two fires" of the insurgency in rural areas and disgust among the populace at the authoritarian nature of his government. His survival might depend on the "reforms he now decides to make to meet such justifiable grievances as may exist among his people."[37]

December

- 4 December

Ambassador Durbrow reported to the State Department that if Diem did not reform his government, "we may well be forced to undertake the difficult task of identifying and supporting alternate leadership."[38]

- 12 December

The National Liberation Front was created at a conference at Xom Giua near the Cambodian border and the city of Tây Ninh.[39] The conference was attended by 100 delegates from more than a dozen political parties and religious groups, but was dominated by the North Vietnamese communist party. The NLF was said to include "all the patriots from all social strata, political parties, religions and nationalities" with the objective of overthrowing the "U.S. imperialists" and its "puppet administration" in Saigon.[40]

A Vietnamese historian has said that the creation of the NLF was to emphasize that the Viet Cong struggle against South Vietnam and the U.S. had legitimate roots in the south and "to give the USSR and China no reason to oppose the armed struggle." Both the Soviet Union and China had been skeptical about the wisdom of North Vietnam attempting to reunite Vietnam by force.[41]

- 29 December

Under pressure from MAAG chief McGarr and the Department of Defense, Ambassador Durbrow withdrew his opposition to the expansion of the ARVN from 150,000 to 170,000 soldiers. The increase would be financed by the United States.[42]

- 31 December

Approximately 900 U.S. military personnel were in Vietnam on this date.[9] Five American soldiers were killed in Vietnam during 1960.[43] South Vietnamese armed forces numbered 146,000 regulars and 97,000 militia.[44] They suffered 2,223 killed in action.[45]

The number of Viet Cong combatants, counting both full-time and part-time guerrillas, was estimated at 15,000.[46] North Vietnam infiltrated 500 soldiers and party cadre, 1,600 weapons, and 50 tons of supplies into South Vietnam during the year.[47]

Bibliography

- Notes

- ↑ Langer 2005, p. 53

- ↑ Spector, Ronald L. United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and support: the early years, 1941-1960 Washington: Superintendent of Documents, 1983, p. 335

- ↑ Spector, pp. 334

- ↑ Pringle, James, "Meanwhile: The quiet town where the Vietnam War began", The New York Times, 223 March 2004

- ↑ "Ben Tre Province", accessed 2 Dec 1963

- ↑ Asselin, Pierre Hanoi's Road to the Vietnam War, 1954-1965 Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013, p. 73

- ↑ Spector, p. 338

- ↑ Spector, p. 349-351

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Vietnam War Timelines: 1958-1960" http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1959.aspx, accessed 26 Aug 2014

- ↑ Adamson, Michael R. "Ambassadorial Roles and Foreign Policy: Elbridge Durbrow, Frederick Nolting, and the U.S. Commitment to Diem's Vietnam, 1957-1961" Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 2 (June 2002), p. 235. Downloaded from JSTOR; Spector, p. 354

- 1 2 Spector, p. 340

- ↑ Spector, p. 357

- ↑ Buzzanco, Robert Masters of War: Military Dissent and Politics in the Vietnam Era Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 71

- ↑ Spector, pp. 341-342

- ↑ Adamson, p. 236

- ↑ Spector, p. 347

- ↑ Asselin, pp. 74-75

- ↑ Daugherty, Leo (2002), New York: Chartwell Books, Inc., p. 19

- 1 2 Spector, p. 343

- ↑ Spector, p. 302

- ↑ Zasloff, Joseph J. “Rural Resettlement in South Vietnam: The Agroville Program”, Pacific Affairs, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Winter 1962-1963), p. 337. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ↑ Spector, p. 354

- 1 2 Daugherty, p. 19

- ↑ Adamson, p. 237

- ↑ Spector, p. 342

- ↑ Spector, p. 355

- ↑ Mann, pp. 218-219; Foreign Relations of the United States 1958-1960, p. 579

- ↑ Asselin, p. 76

- ↑ Spector, p. 364

- ↑ Asselin, p. 78

- ↑ Asselin, p. 83

- ↑ Spector, p. 368

- ↑ Spector, p. 366

- ↑ Asselin, pp. 85-86

- ↑ Doyle, Edward et al, The Vietnam Experience: Passing the Torch Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1981, p. 166

- ↑ Doyle et al, pp. 166-167

- ↑ Doyle et al, p. 167

- ↑ Mann, p. 220

- ↑ Jacobs, Seth Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Dinh Diem and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950-1963 New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2006, p. 119

- ↑ Asselin, pp. 87-88; "December 20, 1960: National Liberation Front formed" http://www.history.com/thisday-in-history/national-liberation-front-formed, accessed 28 Aug 2014

- ↑ Asselin, p. 89

- ↑ Spector, p. 371

- ↑ United States Government, 2010 "Statistical Information about Casualties of the Vietnam War" http://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics.html#date, accessed 29 Aug 2014

- ↑ Lewy, Gunther (1978), America in Vietnam, New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965-1973, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 275

- ↑ Cosmas, Graham A. (2006), MACV The Joint Command in the Years of Escalation, 1962-1967, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 14

- ↑ Stewart, Richard W. (2012), Deepening Involvement 1945-1965, Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 24

- References

- Ang, Cheng Guan (2002). The Vietnam war from the other side: the Vietnamese communists' perspective (2002 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1615-7. - Total pages: 193

- Langer, Howard (2005). The Vietnam War: an encyclopedia of quotations (2005 ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32143-6. - Total pages: 413

- United States, Government (2010). "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

| Vietnam War timeline |

|---|

|

↓ Viet Cong created │ 1955 │ 1956 │ 1957 │ 1958 │ 1959 │ 1960 │ 1961 │ 1962 │ 1963 │ 1964 │ 1965 │ 1966 │ 1967 │ 1968 │ 1969 │ 1970 │ 1971 │ 1972 │ 1973 │ 1974 │ 1975 |