1961 in the Vietnam War

| 1961 in the Vietnam War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

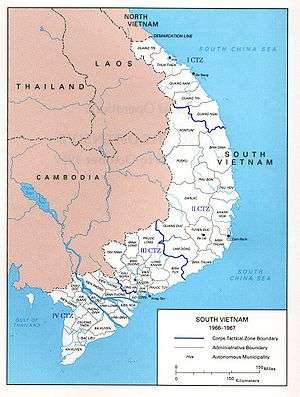

A map of South Vietnam showing provincial boundaries and names and military zones: 1, II, III, and IV Corps. | |||

| |||

| Belligerents | |||

|

Anti-Communist forces: |

Communist forces: | ||

| Strength | |||

|

US: 3205 [1] South Vietnam 330,000.[2] | |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

|

US: 16 killed South Vietnam: 4,004 killed[3] | North Vietnam: casualties | ||

1961 saw a new American president, John F. Kennedy, attempt to cope with a deteriorating military and political situation in South Vietnam. The Viet Cong with assistance from North Vietnam made substantial gains in controlling much of the rural population of South Vietnam. Kennedy expanded military aid to the government of President Ngo Dinh Diem, increased the number of U.S. military advisors in South Vietnam, and reduced the pressure that had been exerted on Diem during the Eisenhower Administration to reform his government and broaden his political base.

The year was marked by halfhearted attempts of the U.S. Army to respond to Kennedy's emphasis on developing a greater capability in counterinsurgency,[4] although the U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group began providing counterinsurgency training to the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) and other security forces. The Kennedy Administration debated internally about introducing U.S. combat troops into South Vietnam, but Kennedy decided against ground soldiers. The CIA began assisting Montagnard irregular forces, American pilots began flying combat missions to support South Vietnamese ground forces, and Kennedy authorized the use of herbicides (Agent Orange) to kill vegetation near roads threatened by the Viet Cong. By the end of the year, 3,205 American military personnel were in South Vietnam compared to 900 a year earlier.

North Vietnam continued to urge the Viet Cong to be cautious in South Vietnam and emphasized the importance of the political struggle against the governments of Diem and the United States rather than the military struggle.

January

- 4 January

U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam Elbridge Durbrow forwarded a counterinsurgency plan for South Vietnam to the State Department in Washington. The plan provided for an increase in the size of the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) from 150,000 to 170,000 to be financed by the United States, an increase in the size of the Civil Guard from about 50,000 to 68,000 to be partially financed by the United States, and a number of administrative and economic reforms to be accomplished by the Diem government.[5]

The counterinsurgency plan was a "tacit recognition that the American effort...to create an [South Vietnamese] army that could provide stability and internal security...had failed.[6]

- 6 January

Soviet Premier Nikita Krushchev announced that the Soviet Union would support Wars of national liberation around the world.[7]

- 14 January

Counterinsurgency expert and Diem friend General Edward Lansdale returned to Washington after a 12-day visit to South Vietnam. Diem had requested the Lansdale visit. Lansdale concluded that the U.S. should "recognize that Vietnam is in a critical condition and...treat it as a combat area of the cold war" Lansdale pushed for Durbrow to be replaced. He called for a major American effort to regain the initiative, including a team of advisers to work with Diem to influence him to undertake reforms.[8]

- 19 January

In a meeting between outgoing President Dwight Eisenhower and President-elect Kennedy, Eisenhower did not mention Vietnam as one of the major problems facing the U.S. Eisenhower described Laos as the "key to Southeast Asia."[9]

- 20 January

John Fitzgerald Kennedy was inaugurated as the 35th U.S. President and declared, "...we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe, to insure the survival and the success of liberty."

- 21 January

CIA operative Edward Lansdale wrote to Secretary of Defense designate Robert McNamara about his recent visit to South Vietnam. "It was a shock," said Lansdale, to find that the Viet Cong "had been able to infiltrate the most productive area of South Vietnam and gain control of nearly all of it except for narrow corridors protected by military actions."[10]

- 24 January

The Politburo in North Vietnam assessed the situation of the Viet Cong in South Vietnam. In the Central Highlands (the Annamite Chain) the Viet Cong were making progress with good support from rural people and the ethnic minority Degar or Montagnards. In the Mekong Delta, however, the situation was less favorable due to the easy access to those areas by the South Vietnamese government. The revolutionary message in the cities was "narrow and weak" as rural cadres and urban dwellers mistrusted each other. The Politburo mandated that the Viet Cong concentrate on political struggle in the South and "avoid military adventurism." They were to prepare for war—but the time for protracted conflict had not yet arrived.

The Politburo also created the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) to coordinate military and political activity in South Vietnam. The U.S. would later devote much military effort to finding and destroying the Communist "Pentagon", but COSVN was always a mobile and widely dispersed organization and never a fixed place.[11]

- 28 January

President Kennedy met with his national security team for the first time. approved the counterinsurgency plan proposed by the Embassy in South Vietnam and authorized the additional funding needed to implement it. The plan called for increasing the size of the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) from 150,000 to 170,000 men.[12]

CIA operative General Edward Lansdale, just returned from a visit to Vietnam, gave Kennedy a pessimistic report on the situation in South Vietnam. Kennedy proposed that Lansdale be named Ambassador to South Vietnam, but the Department of State and CIA successfully opposed the nomination. Lansdale was "not a team player" and "too independent."[13]

- 30 January

Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) chief General Lionel C. McGarr said that Diem had done "a remarkably fine job during his five years in office and negative statements about him were half truths and insinuations. U.S. policy should be to support Diem, not reform his government."[14]

To the contrary, Ambassador Durbrow recommended that Secretary of State Dean Rusk press Diem to reform his government and threaten to withhold aid if he refused.[15]

February

The military force of the National Liberation Front for South Vietnam, the People's Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF) was formed under the leadership of Tran Luong. Prior to this there had been no overall military command of the Viet Cong and the other groups united under the umbrella of the National Liberation Front.[16]

- 13 February

Ambassador Durbrow urged on President Diem a number of specific reforms in accordance with the counterinsurgency plan which conditioned U.S. military and economic aid on reforms in Diem's government. Contrary to Durbrow, MAAG chief General McGarr expressed the view, supported by General Lansdale and Secretary Rusk, that the Department of Defense should oppose conditioning U.S. aid on reform.[15]

March

- 1 March

Secretary of State Rusk told the Embassy in Saigon that Kennedy "ranks the defense of Vietnam among the highest priorities of U.S. foreign policy." He said that President Kennedy was worried that the Diem government would not survive the two years it would take to implement the reforms called for in the counterinsurgency plan.[17]

- 23 March

A U.S. military aircraft gathering intelligence over Laos was shot down. The U.S. decided that henceforth all aircraft operating over Laos would bear Laotian identification markings.[18]

- 28 March

President Kennedy was briefed by the intelligence agencies about the deteriorating situation in South Vietnam. This was the first time that a National Intelligence Estimate expressed doubt about President Diem's ability to deal with the insurgency. Kennedy decided to send 100 additional military advisers to South Vietnam.[18]

- 28 March

President Kennedy had pointed out the importance of counterinsurgency since the first days of his Presidency. In a speech to Congress he said the United States needed "a greater ability to deal with guerrilla forces, insurrections, and subversion." He followed up his speech with proposals to expand the budget and military forces for unconventional war.[19]

April

- 9 April

Diem was re-elected President of South Vietnam with nearly 80 percent of the votes. The Viet Cong attempted to disrupt the election in rural areas.[20]

- 13 April

Robert Grainger Ker Thompson, a British counterinsurgency expert who had helped the British defeat a communist insurgency in Malaya, visited South Vietnam at the invitation of President Diem and presented a report to Diem recommending a Strategic Hamlet Program to defeat the Viet Cong. Thompson would be an important adviser to the South Vietnamese government throughout the Vietnam War, but had only a limited influence on the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations.[21]

- 27 April

The report of a high-level study group headed by Undersecretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric said that "South Vietnam is nearing the decisive phase of its battle for survival" and that the situation is "critical but not hopeless." It recommended that the United States show "our friends, the Vietnamese, and our foes, the Viet Cong, that come what may, the US intends to win this battle."[22]

May

- 2 May

A cease fire was declared in Laos between communist rebels (the Pathet Lao) and government troops. President Kennedy had contemplated American military intervention in Laos but the cease fire damped down tensions between the U.S. and the Soviet Union supporting different Laotian factions.[23]

- 5 May

At a press conference, a reporter asked President Kennedy if he was considering the introduction of American combat troops into South Vietnam. Kennedy said he was concerned about the "barrage" faced by the government of South Vietnam from Viet Cong guerrillas and that the introduction of troops and other help was under consideration.[24]

- 6 May

The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Lyman Lemnitzer told MAAG chief McGarr that "Kennedy was ready to do anything within reason to save Southeast Asia." Lemnitzer opined that "marginal and piecemeal efforts" would not save South Vietnam from a communist victory.[25]

- 10 May

Frederick Nolting, a career diplomat, arrived in Saigon to replace Durbrow as United States Ambassador to South Vietnam. Nolting interpreted his instructions as primarily to improve relations with Diem, strained by Durbrow's hectoring Diem to make social and economic reforms. Nolting would try to influence Diem by agreeing with him and supporting him unconditionally. Prior to this date, Nolting had never set foot in Asia.[26]

- 11 May

Vice President Lyndon Johnson arrived in South Vietnam for a three-day visit. Johnson's instructions were to "get across to President Diem our confidence in him as a man of great stature." Johnson called Diem "the Winston Churchill of Southeast Asia." Johnson also delivered a letter from Kennedy which approved an increase in South Vietnamese military forces from 150,000 to 170,000 soldiers and said that the United States "was prepared to consider a further increase." In a significant change from the policy of Ambassador Durbrow and the Eisenhower Administration, U.S. funding for the increase in military aid was not conditioned on the Diem government undertaking social and economic reforms. Diem, however, declined Kennedy's offer to introduce American combat troops into South Vietnam saying that it would be a propaganda victory for the Viet Cong.

On his return to Washington Johnson noted the disaffection of the Vietnamese people with Diem but concluded that the "existing government in Saigon is the only realistic alternative to Viet Minh [Viet Cong] control."[27]

- 11 May

President Kennedy issued National Security Action Memorandum - 52 which called for a study of increasing South Vietnamese military forces from 170,000 to 200,000; expanded MAAG responsibilities to include aid to the Civil Guard and Self Defense Corps; authorized sending 400 Special Forces soldiers to Vietnam covertly to train ARVN; approved covert and intelligence operations in both North and South Vietnam; and proposed actions to improve relations between President Diem and the U.S.[28]

- 16 May

The International Conference on the Settlement of the Laotian Question convened in Geneva, Switzerland at the behest of Cambodia leader Prince Norodom Sihanouk. The objective of the meeting was to create a neutralist Laos free from superpower rivalries and to reach an amicable end to a civil war. North Vietnam, South Vietnam, the Soviet Union, and the United States were among the countries participating in the conference. North Vietnam supported the concept of a neutral Laos.[29]

June

- 4 June

President Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Krushchev met in Vienna, Austria and expressed support for an international agreement to create a neutral and independent Laos.[30]

- 9 June

President Diem requested that the U.S. subsidize an increase in his military forces from 170,000 to 270,000.[31] The U.S. approved financing an increase of only 30,000 personnel.[30]

- 12 June

Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and North Vietnamese Premier Pham Van Dong in Beijing accused the United States of "aggression and intervention in South Vietnam."[32]

July

- 1 July

General Maxwell Taylor was appointed by Kennedy as the "President's Military Representative." Taylor, a retired General returned to duty by Kennedy, was already a key adviser on Vietnam and military issues.[33]

- 3 July

The U.S. Department of Defense recommended an increase in South Vietnam's armed forces from 170,000 to 200,000.

- 16 July

Ambassador Nolting recommended to Washington that U.S. aid to South Vietnam be increased to finance the expansion of the South Vietnamese army (ARVN), cover a balance of payments deficit, and assure President Diem of the seriousness of the U.S. commitment to his government.[34]

August

Journalist Theodore White wrote a letter to President Kennedy about his visit to South Vietnam. "the situation gets steadily worse almost week by week....Guerrillas now control almost all the Southern delta -- so much that I could find no American who would drive me outside Saigon in his car even by day without military convoy...What perplexes the hell out of me is that the Commies, on their side, seem able to find people willing to die for their cause."[35]

- 1 August

The French diplomatic mission in Haiphong reported widespread dissatisfaction with the North Vietnamese government. Austerity measures and reduced food rations were alienating even the "spouses of the highest ranking personalities in the Regime."[36]

- 10 August

For the first time the United States used herbicides in the Vietnam War. U.S. airplanes sprayed herbicides on forests near Dak To in the Mekong Delta.[37]

September

- 1 September

Two battalions (approximately 1,000 men) of communist troops who had recently infiltrated South Vietnam from Laos, overran the town of Kontum, capital of Kontum province. The communists repelled a rescue effort by ARVN and Civil Guards on September 3 and faded into the jungle before two battalions of ARVN arrived on September 4.[2]

- 15 September

MAAG issued its "Geographically Phased National Level Operation Plan for Counterinsurgency" plan which envisioned the pacification of South Vietnam by the end of 1964. The first step proposed in the plan was a sweep by ARVN through the Viet Cong dominated "Zone D", a forested area 50 miles northeast of Saigon. The South Vietnamese government did not execute the plan, favoring instead an alternative, and much less detailed, plan advanced by British counterinsurgency expert Robert Grainger Ker Thompson.[38]

- 30 September

The United Kingdom established the British Advisory Mission (BRIAM) in Saigon under Robert Thompson who had previously helped defeat the communist insurgency in Malaya. BRIAM would advise President Diem on counterinsurgency strategy and function as an alternative to the U.S. MAAG.[39]

October

- 2 October

Speaking to his National Assembly, President Diem said that "it is no longer a guerrilla war but one waged by an enemy who attacks us with regular units fully and heavily equipped and seeks a decision in Southeast Asia in conformity with the orders of the Communist International.[40]

- 3 October

David A. Nuttle, an International Voluntary Services employee, met with CIA Station Chief William Colby. Tuttle worked with the Rhade people, one of the Montagnard ethnic groups of Darlac province in the Central Highlands about 150 miles (240 km) northeast of Saigon. Colby asked Nuttle to help "create a pilot model of a Montagnard defended village." The CIA and U.S. military were looking for means to combat the growing influence of the Viet Cong in the Central Highlands. Nuttle rejected the proposed strategy of the South Vietnamese government and the MAAG of putting the Montagnards on "reservations" and making the remainder of the Central Highlands a free fire zone. Instead he said that, while the Rhade would not fight for South Vietnam, they would defend their villages and thereby resist Viet Cong control. The CIA decided to initiate a pilot project to implement Tuttle's ideas.[41]

- 6 October

U.S. Ambassador Nolting sent the following message to Washington: "Two of my closest colleagues [Embassy officers Joseph Mendenhall and Arthur Gardiner] believe that this country cannot attain the required unity, total national dedication, and organizational efficiency necessary to win with Diem at helm. This may be true. Diem does not organize well, does not delegate sufficient responsibility to his subordinates, and does not appear to know how to cultivate large-scale political support. In my judgment, he is right and sound in his objectives and completely forthright with us. I think it would be a mistake to seek an alternative to Diem at this time or in the foreseeable future. Our present policy of all-out support to the present government here is, I think, our only feasible alternative."[42]

- 11 October

The Joint Chiefs of Staff presented President Kennedy with a report stating that the defeat of the Viet Cong would require 40,000 American combat troops, plus another 120,000 to guard the borders to deal with threats of invasion or infiltration by North Vietnam or China.[43]

- 13 October

General Richard G. Stilwell, submitted a report to the Secretary of the Army and Army Chief of Staff stating that the efforts of the Army to develop counterinsurgency strategy had been a "failure to evolve simple and dynamic doctrine. The report called for the whole Army to take on counterinsurgency as its mission rather than relegating it to Special Forces[44]

- 18 October

General Maxwell Taylor arrived in Saigon as head of a mission sent by President Kennedy to examine the feasibility of U.S. military intervention in Vietnam. Presidential Adviser Walter Rostow and General Lansdale, a counterinsurgency expert and friend of President Diem, were among the members of his delegation. Taylor proposed a new partnership between South Vietnam and the U.S. that would involve dispatching 8,000 to 10,000 American soldiers to South Vietnam. These soldiers would permit joint planning of military operations, improved intelligence, increased covert activities, more American advisers, trainers, and special forces, and the introduction of American helicopter and light aircraft squadrons. Most significantly, they would also "conduct such combat operations as are necessary for self-defense and for the security of the area in which they are stationed." [45]

During the Taylor visit to South Vietnam President Diem met privately with Lansdale and later requested that he be assigned to South Vietnam. Instead, President Kennedy gave Lansdale the job of attempting to depose or kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro. According to Presidential adviser, Walter Rostow the failure to send Lansdale to South Vietnam was due to jealousy by the State Department and the Defense Department of Lansdale's unique access and influence with President Diem.[46]

- 26 October

North Vietnam's two-track approach, building socialism in the North while providing limited support to the Viet Cong in the South, was criticized by members of the National Assembly in Hanoi who gave a bleak view of the prospects for the revolution in South Vietnam. Increased American aid had increased the ability of the Diem government to oppress its people and to inflict damage on the Viet Cong. They derided the assistance the North had provided to the Viet Cong. One Assemblyman, to make the point about oppression in the South, cited statistics gathered by the National Liberation Front that the Diem government had killed 77,500 people between 1954 and 1960 and imprisoned 270,000 political dissidents.[47]

November

- 2 November

Senator Mike Mansfield, formerly a strong support of President Diem, took exception to Taylor's report. He told President Kennedy to be cautious when contemplating American combat soldiers in Vietnam. Mansfield said, "we cannot hope to substitute armed power for the kind of political and economic social changes that offer the best resistance to communism." If reforms had not been achieved in Vietnam in the previous several years, "I do not see how American combat troops can do it today."[48]

- 4 November

At a Washington meeting and according to his account of the meeting, State Department official George Ball warned General Taylor and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara that introducing 8,000 or more American soldiers into Vietnam might cause "a protracted conflict far more serious than Korea....The Vietnam problem was not one of repelling overt invasion but of mixing ourselves up in a revolutionary situation with strong anti-colonialist overtones."[49] Three other State Department officials also expressed their opposition to the introduction of American combat soldiers: Averell Harriman, Chester Bowles, and John Kenneth Galbraith. Secretary of State Rusk had reservations because Diem was "a losing horse."[50]

- 4 November

The Rhade people of Buon Enao, a village of 400 people six miles from the city of Ban Me Thout, made an agreement with the ARVN and the CIA to serve as a model village to be defended against the Viet Cong. The Rhade conditions were that all ARVN attacks against their villages and their neighbors, the Jarai, would cease, amnesty would be given to all Rhade who had helped the Viet Cong, and the government would provide medical, educational, and agricultural assistance. Buon Enao, in exchange, would create a self-defense force, initially armed only with crossbows and spears, and fortify the village. If proven successful, the Buon Enao model would be replicated elsewhere in the Central Highlands which constituted most of South Vietnam's area, although had only a small share of its population. This was the beginning of the Civilian Irregular Defense Group program.[51]

- 10 November

President Kennedy approved a "selective and carefully controlled joint program of defoliant operations" in Vietnam. The initial use of herbicides was to be for clearance of key land routes, but might proceed to the use of herbicides to kill food crops. This was the beginning of Operation Ranch Hand which would defoliate much of Vietnam during the next decade.[52]

- 11 November

British counterinsurgency expert Robert Thompson presented his plan for pacifying the Mekong Delta to President Diem. The essence of the plan was to win the loyalties of the rural people in the Delta rather than kill Viet Cong. Instead of search and destroy military sweeps by large ARVN forces, Thompson proposed "clear and hold" actions. Protection of the villages and villages was an ongoing process, not an occasional military sweep. The means of protecting the villages would be "strategic hamlets", lightly fortified villages in low risk areas. In more insecure areas, especially along the Cambodian border, villages would be more heavily defended or the rural dwellers relocated.

The British plan and the preference shown it by President Diem caused consternation at MAAG and with its chief, General McGarr. Much of the British plan was contrary to American counterinsurgency plans. However, in Washington many State Department and White House officials received the British plan favorably. Many questioned the view of the Department of Defense that conventional military forces and tactics would defeat the Viet Cong.[53]

- 15 November

At a meeting of the National Security Council President Kennedy expressed doubts about the wisdom of introducing combat soldiers into Vietnam.[54]

- 16 November

Anticipating that President Kennedy would soon decide to dispatch American combat soldiers to South Vietnam, Farm Gate American aircraft began arriving in South Vietnam. A detachment of Jungle Jim Air Commandos was to train the Vietnam Air Force using older aircraft. The Farm Gate aircraft would also have a "second mission of combat operations."[55]

- 22 November

President Kennedy approved National Security Action Memorandum, No. 111 which authorized the U.S. to provide additional equipment and support to South Vietnam, including helicopters and aircraft, to train the South Vietnamese Civil Guard and Self-Defense Corps, and to assist the South Vietnamese military in a number of areas, plus providing economic assistance to the government. The NSAM also called for South Vietnam to improve its military establishment and mobilize its resources of persecute the war. Thus, Kennedy stopped short of what many of his advisers, including General Taylor, had advised: the introduction of U.S. combat soldiers into South Vietnam.[56] Kennedy's decision not to introduce combat troops surprised the Defense Department which had been assembling forces to be assigned to Vietnam, including Farm Gate aircraft.[57] However, Kennedy's decision was a visible and undeniable violation of the Geneva Accords of 1954, still technically in force.[58]

- 22 November

President Kennedy approved the use of herbicides in Viet Nam to kill vegetation along roads and to destroy crops being grown to feed the Viet Cong. The herbicide most used would become known as Agent Orange.[56]

- 27 November

At a White House meeting of top officials President Kennedy complained about the lack of "whole-hearted support" for his policies and demanded to know who at the Department of Defense was responsible in Washington for his Vietnam program. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara said he would be responsible. Kennedy also demanded that Ambassador Nolting in Saigon press Diem to take action to reform his government.[59]

- 30 November

President Kennedy called a meeting of the U.S. Army's top commanders. He expressed disappointment that the army had not moved more quickly to implement his counterinsurgency proposals, saying, "I want you guys to get with it. I know that the Army is not going to develop in this counterinsurgency field and do the things that I think must be done unless the Army itself wants to do it." He followed the meeting up with a memo or Secretary of Defense McNamara saying he was "not satisfied that the Department of Defense, and in particular the Army, is according the necessary degree of attention and effort to the threat of insurgency and guerrilla war."[60]

December

- 1 December

According to French reports from their diplomatic mission in Hanoi, several revolts by peasants and minority groups had been ruthlessly repressed during the previous several months by the North Vietnamese Army and challenges to the government had become rare.[61]

- 4 December

A dozen American Special Forces soldiers arrived in Buon Enao to begin the CIDG project. South Vietnamese Special Forces were already in the village building a dispensary and a fence around the village, and training a 30-man self-defense force. The CIA provided rifles and sub-machine guns to the self-defense force. The Buon Enao experiment was a holistic approach to the threat of the insurgency, relying on social and economic programs as well as military measures to create an anti-communist movement among the Montagnard people who traditionally mistrusted Vietnamese of all political persuasions.[62]

- 5 December

Air Force General Curtis LeMay urged the Joint Chiefs of Staff to try to persuade President Kennedy to approve the introduction of substantial combat forces into South Vietnam.[63]

- 11 December

"The first fruits" of the Taylor mission arrived in Saigon: 32 CH-21 Shawnee 20-passenger helicopters, four single-engine training planes, and about 400 American soldiers.[64]

- 16 December

Secretary of Defense McNamara met with senior U.S. military leaders in Hawaii to discuss the implementation of the expanded military aid to South Vietnam. He listed three tenets: (1) We have great authority from the President; (2) Money is no object; and (3) The one restriction is that combat troops will not be introduced. In closing the meeting McNamara said the job of the U.S. military "was to win in South Viet Nam and if we weren't winning to tell him what was needed to win."[65]

- 22 December

Cryptologist Corporal James T. Davis became the first American member of the United States Army Security Agency to be killed in Vietnam. He and 8 South Vietnamese soldiers were ambushed by the Viet Cong while on patrol.[66]

- 31 December

U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam numbered 3,205 compared to 900 at the end of 1960.[1] Sixteen American soldiers were killed in Vietnam in 1961 compared to nine in the previous five years.[67] South Vietnamese military forces numbered almost 180,000 and police, militia, and paramilitary numbered 159,000.[68] The South Vietnamese armed forces suffered 4,004 killed in action, nearly double the total killed in the previous year.[69]

- 31 December

During 1961, North Vietnam infiltrated 6,300 persons, mostly southern communists who had migrated to North Vietnam in 1954-1955, and 317 tons of arms and equipment into South Vietnam. There were approximately 35,000 communist party members in South Vietnam. The Viet Cong were estimated by the United States to control 20 percent of the 15 million people in South Vietnam and influence 40 percent. In the rice-growing Mekong Delta, the Viet Cong were believed to control seven of the 13 provinces.[70]

Notes

- 1 2 "Vietnam War Timeline: 1961-1962" http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1961.aspx, accessed 1 Sep 2014

- 1 2 Stewart, Richard W. (2012), Deepening Involvement 1945-1965, Washington, D.C.: Center for Military History, United States Army, p. 40

- ↑ Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965-1973, Washington, D.C: Center of Military History, United States Army, p. 275

- ↑ Krepinevich, Jr, Andrew F., The Army and Vietnam, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986, pp. 27-38; Nagl, John A., Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002, pp. 124-129

- ↑ Spector, Ronald L. United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and support: the early years, 1941-1960, p. 371

- ↑ Spector, p. 372

- ↑ Daugherty, Leo (2002), "The Vietnam War Day by Day, New York: Chartwell Books, Inc., p. 20

- ↑ Adamson, Michael R. "Ambassadorial Roles and Foreign Policy: Elbridge Durbrow, Frederick Nolting, and the U.S. Commitment to Diem's Vietnam, 1957-1961", Pacific Studies Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 2 (June 2002), p. 243. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ↑ Doyle, Edward et al, The Vietnam Experience: Passing the Torch Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1981, p. 169

- ↑ Lathan, Michael E. (2006), "Redirecting the Revolution? The USA and the Failure of Nation Building in South Vietnam" Third World Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 1, p. 30

- ↑ Asselin, Pierre, Hanoi's Road to the Vietnam War, 1954-1965, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013, pp. 92-95; Time "Just How Important are Those Caches?" 1 June 1970, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,878283-1,00.html, accessed 1 Sep 2014

- ↑ Doyle et al, p. 180; Daugherty, p. 20

- ↑ Langguth, A. J. (2000), Our Vietnam: The War 1954-1975, New York: Simon & Schuster, pp 113-117

- ↑ Adamson, p. 244

- 1 2 Adamson, p. 245

- ↑ Li 2007, p. 216

- ↑ Buzzanco, Robert Masters of War: Military Dissent and Politics in the Vietnam Era Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 92

- 1 2 Daugherty, p. 20

- ↑ "Krepinevich, Jr., pp. 66-67

- ↑ Doyle, pp 182-183

- ↑ Nagl, p. 130

- ↑ Cable, Larry E. (1986), Conflict of Myths: The Development of American Counterinsurgency Doctrine and the Vietnam War, New York: New York University Press, p. 188

- ↑ Mann, Robert, A Grand Delusion: America's Descent into Vietnam, New York: Basic Books, 2001, p. 231

- ↑ "May 5, 1961, Press Conference" http://www.historycentral.com/JFK/Press/5.5.61.html, accessed 4 Nov 2014

- ↑ Buzzanco, pp 92-93

- ↑ Adamson, p. 249

- ↑ Jacobs, Seth, Cold War Mandarin: Ngo Diem Dinh and the Origins of America's War in Vietnam, 1950-1963 New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 2006, pp. 123-125

- ↑ Adamson, p. 247

- ↑ Asselin, pp 120-122

- 1 2 Daugherty, p. 21

- ↑ Buzzanco, p. 98

- ↑ Daugherty, pp 21-22

- ↑ Foreign Relations of the United States https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v01/persons, accessed 30 Aug 2014

- ↑ Adamson, pp. 249-250

- ↑ Latham, Michael E. "Redirecting the Revolution? The USA and the Failure of Nation-Building in South Vietnam", Third World Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2006, p. 30. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ↑ Asselin, p.99

- ↑ "First Herbicides Sprayed in Vietnam" http://www.historychannel.com.au/classroom/day-in-history/746/first-herbicides-sprayed-in-vietnam

- ↑ Krepinevich, Jr., pp. 66-67

- ↑ "Vietnam War Timelines: 1961-1962" http://www.vietnamgear.com/war1961.aspx, accessed 3 Sep 2014

- ↑ Daugherty, pp. 22-23

- ↑ Harris, Paul "The Buon Enao Experiment and American Counterinsurgency" Sandhurst Occasional Papers, No. 13, Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, 2013, p. 13-14

- ↑ Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-63, Vol. 1, Vietnam, 1961 Department of State, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v01, accessed 30 Aug 2014

- ↑ Daugherty, p. 23

- ↑ Krepinevich, Jr. pp. 43-44

- ↑ Mann, p. 245; Newman, John M., JFK and Vietnam: Deception, Intrigue, and the Struggle for Power, New York: Warner Books, 1992, p. 134

- ↑ Phillips, Rufus (2008), Why Vietnam Matters, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 105

- ↑ Asselin, 117

- ↑ Mann, pp. 245-246

- ↑ McMann, p. 247

- ↑ Newman, John M. JFK and Vietnam: Deception, Intrigue, and the Struggle for Power New York: Warner Books, 1992, p. 137

- ↑ Harris, pp 15-16

- ↑ Buckingham, Jr., p. 21.

- ↑ The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Vol. 2, Chapter 2, "The Strategic Hamlet Program, 1961-1963, pp. 128-159

- ↑ Mann, pp 250-251

- ↑ Hit My Smoke! Forward Air Controllers in Southeast Asia. p. 12.; Newman, p. 149

- 1 2 Mann, p. 251

- ↑ Newman, p, 149

- ↑ Logevall, Frederick, Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999, p. 33

- ↑ Newman, pp. 146-149

- ↑ Krepinevich, Jr., p. 31

- ↑ Asselin, pp. 99-100

- ↑ Harris, pp. 16-18

- ↑ Newman, p. 162

- ↑ Mann, p. 253; The New York Times, pg. 21, December 12, 1961

- ↑ Newman, p. 158, 162

- ↑ "Sp/4 James "Tom" Davis", http://www.asalives.org/ASAONLINE/kiadavis.htm, accessed 1 Sep 2014

- ↑ "Statistical Information about Fatal Casualties of the Vietnam War", http://www.archives.gov/research/military/vietnam-war/casualty-statistics.html, accessed 1 Sep 2014

- ↑ Stewart, p. 47

- ↑ Clarke, Jeffrey J. (1988), United States Army in Vietnam: Advice and Support: The Final Years, 1965-1973, Washington, D.C: Center of mIlitary History, United States Army, p. 275

- ↑ Asselin, p. 243-244; Stewart, pp. 24-25, 47

References

- Buckingham, Jr., William A. (1982), Operation Ranch Hand: The Air Force and Herbicides in Southeast Asia, 1961-1971, Washington: Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force.

- Hall, Billy (2009). Bulletproof: In Vietnam (2009 ed.). AuthorHouse. ISBN 1-4490-4227-9. - Total pages: 224

- Li, Xiaobing (2007). A history of the modern Chinese Army (2007 ed.). University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2438-7. - Total pages: 413

- United States, Government (2010). "Statistical information about casualties of the Vietnam War". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

| Vietnam War timeline |

|---|

|

↓ Viet Cong created │ 1955 │ 1956 │ 1957 │ 1958 │ 1959 │ 1960 │ 1961 │ 1962 │ 1963 │ 1964 │ 1965 │ 1966 │ 1967 │ 1968 │ 1969 │ 1970 │ 1971 │ 1972 │ 1973 │ 1974 │ 1975 |