Peak coal

The term Peak coal is used to refer to the point in time at which coal production and consumption reaches its maximum, after which, it is assumed, production and consumption will decline steadily. The term was originally used in connection with M. King Hubbert's Hubbert peak theory, in which the finite nature of the resource determines a constraint on production. However, since the expansion of renewable energy particularly in electricity generation, the term is now commonly used with reference to a peak in coal demand, which may already have occurred.

Hubbert's theory

According to M. King Hubbert's Hubbert peak theory, Peak coal is the point in time at which the maximum global coal production rate is reached, after which, according to the theory, the rate of production will enter a terminal decline. Coal is a fossil fuel formed from plant matter over the course of millions of years. It is a finite resource and thus considered to be a non-renewable energy source.

There are two different possible peaks: one measured by mass (i.e. metric tons) and another by energy output (i.e. petajoules). The world average heat content per mass of mined coal rose from 8,020 BTU/lb. in 1989 to 9,060 BTU/lb. in 1999. Since 1999, the world average heat content of mined coal has been fairly steady, and was 9,030 BTU/lb. in 2011.[1]

The estimates for global peak coal extraction vary wildly. Many coal associations suggest the peak could occur in 200 years or more, while scholarly estimates predict the peak to occur as soon as the immediate future. Research in 2009 by the University of Newcastle in Australia concluded that global coal extraction could peak sometime between the present and 2048.[2] A 2007 study by the German Energy Watch Group predicted that global peak coal extraction may occur sometime around 2025 at 30 percent above the 2005 rate.[3][4]

The contemporary concept of peak coal follows from Hubbert peak theory, which is most commonly associated with Peak oil. Hubbert concluded that each oil region and nation has a Bell-shaped depletion curve.[5] However, this question was originally raised by William Stanley Jevons in his book The Coal Question in 1865.

Hubbert noted that United States coal extraction grew exponentially at a steady 6.6% per year from 1850 to 1910. Then the growth leveled off. He concluded that no finite resource could sustain exponential growth. At some point, the rate of extraction will have to peak and then decline until the resource is exhausted. He theorized that extraction rate plotted versus time would show a bell-shaped curve, declining as rapidly as it had risen.[6] Hubbert used his observation of the US coal extraction to predict the behavior of peak oil.

The Hubbert Linearization using yearly production rates has weaknesses for peak coal calculation, as the signal-to-noise ratio is inferior with coal mining data compared to oil extraction. As a consequence, Rutledge[7] uses cumulative production for linearization. By this method the estimated ultimate recovery results in a stable fit for active coal regions. The ultimate production for world coal is estimated to be 680 Gt, of which 309 Gt have already been produced. However, in 2013 the World Coal Association reported that two different estimates of coal reserves remaining were 1038 and 861 Gt.[8]

Peak coal demand

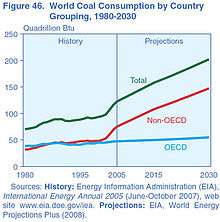

Although reserves of coal remain abundant, consumption of coal has declined in many countries, with some becoming "coal-free".[9] This decline has resulted from the replacement of coal-fired electricity by gas and renewable energy, along with the decline of the steel industry in some countries. As a result, the term "peak coal" is now used primarily to refer to a peak and subsequent decline in global and national coal consumption. According to a number of estimates, China, the world's largest coal consumer, reached peak coal in 2013, and the world may already passed peak coal.[10]

Peak coal production for individual nations

As of 2011, the top coal-extracting countries were China (46% of world extraction), United States (13%), India (7.8%), Australia (5.4%), and Indonesia (4.9%). Four out of five of these largest coal-extracting countries, the exception being the United States, had experienced significant increases in coal extraction over the previous decade.[11]

People's Republic of China

The People's Republic of China is the world’s largest coal extractor and has the third largest reserves after Russia and the United States. The Energy Watch Group predicted that the Chinese extraction will peak around 2015 in their 2007 report, and then revised that to 2020 in their March 2013 report.[3][12] The EWG also predicts that the recent steep rise in extraction will be followed by a steep decline after 2020. Another study puts the peak at 2027.[13] The US Energy Information Administration projects that China coal extraction will continue to rise until 2030.[14]

United States

Although Hubbert's analysis in 1956 projected total extraction to peak in about 2150,[5] records show that extraction reached an energy peak in 1998 and a tonnage peak in 2008.[15]

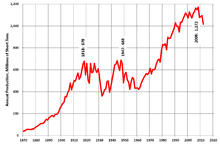

Coal mass

US coal extraction peaked during World War I, then declined sharply during the depression years of the 1930s. Coal extraction peaked again in the 1940s, then declined during the 1950s.[5] Then coal extraction revived, and was on a nearly continual increasing trend from 1962 to 2008, exceeding the previous peaks. Extraction in 2008 was a record 1.17 billion short tons.[16] High-BTU anthracite coal peaked in 1914;[5] and declined from 44 million tons in 1950 to 1.6 million tons in 2007. Bituminous coal extraction has also been declining since 1990. The gap has been taken up by large increases in subbituminous coal extraction.[16] Comprehensive analysis of historical trends in US coal extraction and reserve estimates, along with a possible future outlook, was published in scientific journals on coal geology in 2009.[17]

In 1956, Hubbert estimated that US coal extraction would peak in about the year 2150.[5] In 2004, Gregson Vaux used the Hubbert model to predict peak US coal extraction in 2032.[18] In 2014, a model published in the International Journal of Coal Geology forecast a U.S. raw tonnage peak from between 2009 and 2023, with the most likely year of the peak in 2010.[19]

Energetic peak

Over the years, the average energy content per ton of coal mined in the US has declined as mining shifts to coals of lower rank. Although the tonnage of coal mined in the United States reached its latest peak in 2008, the peak in terms of coal energy content occurred in 1998, at 598 Millions of metric tons of oil equivalent (Mtoe); by 2005 this had fallen to 576 Mtoe, or about 4% lower.[3][20]

Australia

Australia has substantial coal resources, mostly brown coal. It is responsible for almost 40% of global coal exports worldwide, and much of its current electricity is generated from coal-fired power stations. There are tentative plans to very slowly phase out coal electricity generation in favor of gas, although these plans are still a topic of much debate in Australian politics.

Long-term plans for coal in Australia include large-scale export of brown coal to large developing nations such as China and India.[21] Other groups such as the Australian Greens, suggest that coal be left in the ground to avoid its potential combustion either in Australia or in importer nations.

Research in 2009 by the University of Newcastle in Australia concluded that Australian coal extraction could peak sometime after 2050.[2] While the Australian Coal Association (ACA) optimistically estimates that Australia's identified black coal resources could last more than 200 years based on rate of extraction in 2007. This does not account for brown coal stocks.[22]

New South Wales

According to calculations conducted for the Hunter Community Environment Centre in Newcastle, the Australian state of New South Wales 10,600 million tonnes of coal reserves would be exhausted by 2042, based on current industry growth and extraction rates of about 3.2 per cent a year.[22]

United Kingdom

Coal output peaked in 1913 in Britain at 287m tons and now accounts for less than one percent of world coal extraction. 2007 extraction was around 15m tons.[23]

Canada

According to the Earth Watch Group, Canadian coal extraction peaked in 1997.[3]

Germany

Germany hit peak hard coal extraction in 1958 at 150 million tons. In 2005 hard coal extraction was around 25 million tons.[3] Total coal extraction peaked in 1985 at 578 million short tons, declined sharply in the early 1990s following German reunification, and has been nearly steady since 1999. Total coal extraction in 2005 was 229 million short tons, four percent of total world extraction.[11]

World peak coal

- 2011 Patzek and Croft

In 2010, Tadeusz Patzek (chairman of the Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering at the University of Texas at Austin) and Greg Croft, predicted that coal production would peak in 2011 or shortly thereafter, and decline so quickly as to nearly eliminate the contribution of coal to climate change. Patzek said: "Our ability to produce this resource at 8 billion tons per year, in my mind, is a dream,"[24] However, world coal production exceeded 8 billion tons per year in 2012 (8.2 billion), 2013 (8.19 billion), and 2014 (8.085 billion).[25]

- 2150 M. King Hubbert

M. King Hubbert's 1956 projections from the world extraction curve estimated that world coal production would peak at approximately six billion metric tons per year at about the year 2150.[26]

- 2020 Energy Watch Group

Coal: Resources and Future Production,[3] published on 5 April 2007 by the Energy Watch Group (EWG) found that global coal extraction could peak in as few as 15 years.[27] However, the graphs in their 2013 report show a peak in 2020.[12] Reporting on this, Richard Heinberg also notes that the date of peak annual energetic extraction from coal will likely come earlier than the date of peak in quantity of coal (tons per year) extracted as the most energy-dense types of coal have been mined most extensively.[28]

- Institute for Energy

The Future of Coal by B. Kavalov and S. D. Peteves of the Institute for Energy (IFE), prepared for European Commission Joint Research Centre, reached conclusions similar to those of Energy Watch Group, and stated that "coal might not be so abundant, widely available and reliable as an energy source in the future".[27] Kavalov and Peteves did not attempt to forecast a peak in extraction.

- US Energy Information Administration projects world coal consumption to increase through 2035.[29]

See also

References

- ↑ US EIA, International Energy Statistics, accessed 16 May 2015.

- 1 2 "Research forecasts world coal production could peak as soon as 2010". The University of Newcastle, Australia. 28 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Coal: Resources And Future Production" (PDF). Energy Watch Group. 10 July 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

- ↑ "Uranium Resources and Nuclear Energy" (PDF). Energy Watch Group. December 2006. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 M. King Hubbert (June 1956). "Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice'" (PDF). API. p. 36. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- ↑ M. King Hubbert (June 1956). "Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice'" (PDF). API. p. 8. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- ↑ David Rutledge (January 2011). "Estimating long-term world coal production with logit and probit transforms". International Journal of Coal Geology. 85 (1): 23–33. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2010.10.012. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- ↑ "Resources". World Coal Association.

- ↑ "Scotland closes last coal plant".

- ↑ "Global coal peak 2013".

- 1 2 "World coal production". US Energy Information Agency.

- 1 2 "Fossil and Nuclear Fuels – the Supply Outlook" (pdf). Energy Watch Group. March 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ↑ "The Oil Drum - Peak Coal and China".

- ↑ "International Energy Outlook 2008" (PDF). US Enegy Information Administration. p. 52. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ↑ {{cite web url=http://www.eia.gov/beta/international/|title =US EIA}}

- 1 2 US Energy Information Agency: Coal production, selected years, 1949-2007

- ↑ Höök, Mikael; Aleklett, Kjell (2009). "Historical trends in American coal production and a possible future outlook" (PDF). International Journal of Coal Geology.

- ↑ Gregson Vaux (27 May 2004). "The Peak in U.S. Coal Production". From the Wilderness. Retrieved 30 June 2008.

- ↑ Reaver, Nathan G.F.; Khare, Sanjay V. (September 2014). "Imminence of peak in US coal production and overestimation of reserves". International Journal of Coal Geology. 131: 90–105. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2014.05.013.

- ↑ Heinberg, Richard (21 May 2007). "Peak coal: sooner than you think". EnergyBulletin.net.

- ↑ "Brown promises allure of gold in new coal economy". The 7:30 Report. 15 May 2012.

- 1 2 "Reserves to dry up as clean coal becomes viable". The Sydney Morning Herald. 10 April 2007.

- ↑ David Strahan (5 March 2008). "Lump sums". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ↑ Patrick Reis, "Study: World's 'Peak Coal' Moment Has Arrived", New York Times, 29 Sept. 2010.

- ↑ World Mineral Production 2010-14, British Geological Survey, 2016.

- ↑ M. King Hubbert (June 1956). "Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice'" (PDF). API. p. 21. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- 1 2 Richard Heinberg (21 May 2007). "Peak coal: sooner than you think". Energy Bulletin. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ↑ Richard Heinberg (March 2007). "burn the furniture". Richard Heinberg. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ↑ US Energy Information Administration. "International Energy Outlook 2011". Retrieved 29 January 2013.

Further reading

- "Statistical Review of World Energy 2008". Beyond Petroleum. Archived from the original on 22 August 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- "Coal Data, Reports, Analysis". US Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- "McCloskey's Coal Report". McCloskey Coal. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- "Energy Export Databrowser". Mazama Science. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- "World: Mining - Coal Mining - Industry Overview". MBendi. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- David Strahan (19 January 2008). "Coal: Bleak outlook for the black stuff". New Scientist (2639). Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Graham Stewart (13 September 2008). "Remember when coal was going to run out?". London: Sunday Times.