Gunung Leuser National Park

| Gunung Leuser National Park | |

|---|---|

| Taman Nasional Gunung Leuser | |

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

Park entrance | |

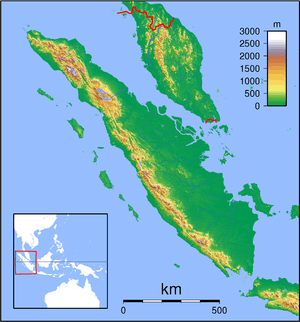

Gunung Leuser NP Location in Sumatra | |

| Location | Sumatra, Indonesia |

| Coordinates | 3°30′N 97°30′E / 3.500°N 97.500°ECoordinates: 3°30′N 97°30′E / 3.500°N 97.500°E |

| Area | 792,700 hectares (1,959,000 acres; 7,927 km2) |

| Established | 1980 |

| Governing body | Ministry of Environment and Forestry |

| World Heritage Site | 2004 |

| Website | gunungleuser.or.id |

| Official name | Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | vii, ix, x |

| Designated | 2004 (28th session) |

| Reference no. | 1167 |

| State Party | Indonesia |

| Region | Asia-Pacific |

| Endangered | 2011–present |

Gunung Leuser National Park is a national park covering 7,927 km2 in northern Sumatra, Indonesia, straddling the border of North Sumatra and Aceh provinces,[1] a fourth portion and three fourths portion, respectively. The national park, settled in the Barisan mountain range, is named after Mount Leuser (3,119 m), and protects a wide range of ecosystems. An orangutan sanctuary at Bukit Lawang is located within the park. Together with Bukit Barisan Selatan and Kerinci Seblat national parks, it forms a World Heritage Site, the Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra.[2]

Geography

Gunung Leuser National Park is 150 km long, over 100 km wide and is mostly mountainous. 40% of the park, mainly in the north-west, is steep, and over 1,500 m. This region is billed as the largest wilderness area in South-East Asia and offers wonderful trekking. 12% of the park, in the lower southern half, is below 600 meters. Eleven peaks are over 2,700 m. Mount Leuser (3,119 m) is the third highest peak on the Leuser Range. The highest peak is Mount 'Tanpa Nama' (3,466 m), the second highest peak in Sumatra after Mount Kerinci (3,805 m).

Ecology

Gunung Leuser National Park is one of the two remaining habitats for Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii).[3] In 1971, Herman Rijksen established the Ketambe Research Station, a specially designated research area for the orangutan.[4] Other mammals found in the park are the Sumatran elephant, Sumatran tiger, Sumatran rhinoceros, siamang, Sumatran serow, sambar deer and leopard cat.[5]

After researchers put 28 camera-traps in July 2011, 6 months later the researchers found one male and six females and predicted the population is not more than 27 Sumatran rhinos which total population predicted is around 200 in Sumatra and Malaysia, half the population of 15 years ago.[6]

Water supply

The first signs of reduced water replenishment have already been seen in and around the Leuser Ecosystem. Groundwater reservoirs are rapidly being exhausted and several rivers fall completely dry during part of the year. This has severe consequences for the local community. Both households and industries need to anticipate water shortages and higher costs for water.[7]

Fishery

Coastal fisheries and aquaculture in and around Leuser are very important. They provide a large portion of the animal protein in local people’s diets and generate ample foreign exchange. Their annual value currently exceeds US $171 million. If the Leuser Ecosystem is degraded, the decline in fresh water may have a detrimental impact on the functioning of the fishery sector.[7]

Flood and drought prevention

Flooding generally becomes more frequent and more destructive as a result of converting forests to other uses. Annual storm flows from a secondary forest are about threefold higher than from a similar-sized primary forest catchment area (Kramer et al., 1995). In Aceh, local farmers have reported an increasing frequency of drought and damaging floods due to degradation of the watercatchment area. In May 1998, over 5,000 ha of intensive rice growing areas were taken out of active production. This was the result of the failure of 29 irrigation schemes due to a water shortage. Furthermore, floods in December 2000 cost the lives of at least 190 people and left 660,000 people homeless. This cost the Aceh province almost US $90 million in losses (Jakarta Post, 2000a). Logging companies are slowly recognising their role in increased flooding and have made large donations to support the victims (Jakarta Post, 2000b).[7]

Agriculture and plantations

Agriculture is a major source of income for the local communities around Leuser. Large rubber and oil palm plantations in northern Sumatra play a major role in the national economy. Almost all remaining lowland forest has been given out officially for oil palm plantations. Yield decline has been recorded, however, in several Leuser regencies. This decline can be ascribed mainly to a deterioration of nutrients in the soil, along with soil erosion, drought and floods, and an increase in weeds. Clearly, these causes of decline are linked to the deforestation of Leuser. For example, the logging of water-catchment areas in Leuser is found to be responsible for taking 94% of failed irrigation areas out of production (BZD, 2000a).[7]

Hydro-electricity

Several regencies, such as Aceh Tenggara, have hydro-electricity plants that use water from Leuser. The plants operated in Aceh Tenggara are designed as small-scale economic activities. It appears that the operational conditions for the hydro-plants have worsened in recent years. Increased erosion of the waterways has forced the operators to remove excessive sediments from their turbines. This has led to frequent interruption of the power supply, higher operational costs and damage to the blades of the turbines. One plant closed down due to lack of water supply. Most of these disturbances are considered abnormal and may therefore be attributed to deforestation.[7]

Tourism

Low-impact eco-tourism can be one of the most important sustainable, non-consumptive uses of Leuser, thereby giving local communities powerful incentives for conservation. Given the opportunities to view wildlife such as orang-utans, some experts view eco-tourism as a major potential source of revenue for communities living around Leuser (van Schaik, 1999).[7] Further information please check out Natural Tourism of Indonesia page.

Path to the summit of Mount Kemiri

Path to the summit of Mount Kemiri Jungle view

Jungle view Tourist village

Tourist village Mount Leuser sunrise

Mount Leuser sunrise

- Tangkahan trekking

7 to 8 hours drive from Medan, Tangkahan is visited by 4,000 foreign tourists and 40,000 domestic/local tourists a year. Modest inns are available, but generation set electricity is limited. Many of Tangkahan people nowadays work for tourism and avoid illegal logging, with education sometimes are not pass the elementary school, but with trained, they can serve the tourists well. All tourists should enter Tangkahan Visitor Center first, and choose the various packages up to 4 days 3 nights package, the prices are fixed even for the porters. Trekking can be done by foot or using elephants.[8]

Biodiversity

People living in areas with a high biodiversity value tend to be relatively poor. Hence, the highest economic values for biodiversity are likely to be found within institutions and people in wealthy countries. Funds can come from several sources, including bio-prospecting, the GEF and grants from international NGOs (with donations possibly being proportional to biodiversity value) (Wind and Legg, 2000).[7]

Carbon sequestration

Anthropogenic increases in the concentrations of greenhouse gases (such as CO2) in the atmosphere lead to climate change. Carbon sequestration by rainforest ecosystems therefore has an economic value, since the carbon fixed in the ecosystem avoids further increase in atmospheric concentrations.[7]

Fire prevention

To what extent does primary rainforest have a fire prevention function, and thus an additional value for preventing economic damage? There are various factors that make disturbed forest more prone to fires than primary forests. The likelihood that a forest will burn depends on the level of fire hazard and fire risk: (1) fire hazard is a measure of the amount, type and dryness of potential fuel in the forest. Logged forest has relatively large amount of dry logging wastes lying around; (2) Fire risk is a measure of the probability that the fuel will ignite. In the presence of abandoned logging roads, which provide easy access to otherwise remote forests, the fire risk is greatly increased when settlers use fire for land clearance.[7]

Non-timber forest products

NTFP can provide local communities with cash as long as exploitation does not surpass a threshold level.[7]

Threats

In November 1995, the Langkat Regency government proposed a road to connect an old enclave, known as Sapo Padang, inside the park. In pursuit of business opportunities, 34 families who had been living in the enclave formed a cooperative in March 1996 and subsequently submitted a proposal to develop an oil palm plantation in August 1997.[9] The oil palm proposal was accepted by the regency and the head of the park agreed to the road construction.

In accordance to the government's Poverty Alleviation Program, the oil palm project proceeded with 42.5 km2 of clearance area, but the project caused major forest destruction in the park during its implementation.[9] The local cooperation unit formed a partnership with PT Amal Tani, which has strong relationship with the military command in the area.[note 1] In January 1998, the Indonesian Forest Ministry granted a permission of 11 km road to be built. In June 1998, local office of the Forestry Service issued a decree stating that the Sapo Padang enclave was no longer legally a part of the national park, a controversial decision which consequently led to further forest destruction during the road construction and invited newcomers to slash and burn forest area to create local plantations a way deeper to the park.

In 1999, two university-based NGOs filed a legal suit to the Medan State Court, while a group of 61 lawyers brought a parallel case in the National Administrative Court. In July 1999, the National Administrative Court rejected the case, while the local NGOs won with 30 million rupiahs damage, but the legal process continues with appeals.[9] The legal process did not stop the project that extensive logging and clearing, road-building and oil palm plantation continue operating inside the national park.

2011 reports the pressures on locals from palm oil profits has led to illegal slash and burning of 21,000 hectares per year.

- "Despite being protected by federal law from any form of destructive encroachment, illegal logging is still rampant in the forest, with the foliage of the Leuser ecosystem disappearing at a rate of 21,000 hectares per year."[10]

Relocations

In December 2010, 26 families comprising 84 people were moved from Gunung Leuser National Park area to Musi Banyuasin, South Sumatra. There are thousands of people who inhabit the park illegally, and the Indonesian government plans to move them. Many of the inhabitants are refugees from the violence and disasters in Aceh.[11]

See also

- List of national parks of Indonesia

- List of World Heritage Sites in Asia

- List of Biosphere Reserves in Indonesia

Notes

- 1 PT Amal Tani was owned by the immediate family of the commander of the Indonesian army's territorial military command of the area, KODAM I Bukit Barisan. The principal function of the military partnership is to organize "administrative details" when obtaining permissions to build the roads and other related projects. The director of PT Amal Tani became the executive of the local cooperation unit. The military's unit charitable foundation, Yayasan Kodam I Bukit Barisan, also involved in the project.[9]

References

- ↑ World Database on Protected Areas: Entry of Gunung Leuser National Park

- ↑ "Tropical Rainforest Heritage of Sumatra". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ↑ S. A. Wich; I. Singleton; S. S. Utami-Atmoko; M. L. Geurts; H. D. Rijksen; C. P. van Schaik (2003). "The status of the Sumatran orang-utan Pongo abelii: an update". Flora & Fauna International. 37 (1): 49. doi:10.1017/S0030605303000115.

- ↑ S. A. Wich; S. S. Utami-Atmoko; T. M. Setia; H. D. Rijksen; C. Schürmann, J.A.R.A.M. van Hooff and C. P. van Schaik (2004). "Life history of wild Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii)". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (6): 385–398. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.08.006. PMID 15566945.

- ↑ Ministry of Forestry: Gunung Leuser National Park, retrieved 2010-01-07

- ↑ "Tujuh Badak Sumatra Tertangkap Kamera". August 10, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Pieter J.H. van Beukering; Herman S.J Cesar; Marco A. Janssen (2003). "Economic valuation of the Leuser National Park on Sumatra, Indonesia". Ecological Economics. 44 (1): 43–62. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00224-0.

- ↑ "Mencecap Keindahan Alam di Tangkahan". April 12, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Emily Matthews, Global Forest Watch (Organization) and Forest Watch Indonesia (Organization) (2002). The State of Forest in Indonesia (PDF). Box 2.3. Oil Palm Development in Gunung Leuser National Park, p. 21. Washington DC: World Resources Institute. ISBN 1-56973-492-5. Retrieved 2007-01-11.

- ↑ Ulara Nakagawa; Inside Indonesia’s ‘Burning Forests’ (2011). "The State of Gunung Leuser National Park". Washington DC: The Diplomat. Retrieved 2011-07-11.

- ↑ "Mt. Leuser National Park evictions on hold". thejakartapost.com.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gunung Leuser National Park. |

- Gunung Leuser National Park (Indonesian)

- Gunung Leuser National Park - faceBook

- Leuser Ecosystem

- Leuser International Foundation

- Ministry of Forestry: Brief description

-

Gunung Leuser National Park travel guide from Wikivoyage

Gunung Leuser National Park travel guide from Wikivoyage