Hendler Creamery

|

Hendler Creamery | |

|

Hendler Creamery in 2011 | |

| |

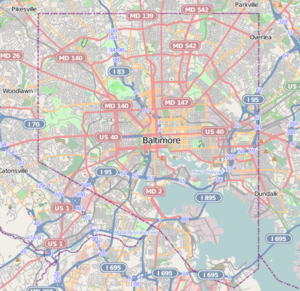

| Location | 1100 E. Baltimore St. & 1107 E. Fayette St., Baltimore, Maryland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°17′28″N 76°36′8″W / 39.29111°N 76.60222°WCoordinates: 39°17′28″N 76°36′8″W / 39.29111°N 76.60222°W |

| Area | 1.5 acres (0.61 ha) |

| Built | 1892 |

| Architect | Jackson C. Gott |

| Architectural style | Romanesque, Early Commercial |

| NRHP Reference # | 07001032[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 20, 2007 |

Hendler Creamery is a historic industrial complex in Jonestown, Baltimore, Maryland. Since it spans an entire block it has addresses at 1100 E. Baltimore St. and 1107 E. Fayette St. "The Hendler Creamery is historically significant for its contribution to the broad patterns of history in three areas of significance: transportation, performing arts, and industry."[2]

Varying usages

Construction and architect

The Hendler Creamery consists of two adjacent building complexes. The original 59,340-square-foot (5,513 m2) three-story brick Richardsonian Romanesque building was constructed as a cable car powerhouse in 1892, replacing five old houses on the site.[3] This use necessitated massive arched doors and a mezzanine floor.[4] The construction is of red face brick with red mortar joints and Potomac red Seneca stone trim, and contains much architectural detailing. The front on East Baltimore Street includes four large contiguous Romanesque Revival half-round arched openings with our pairs of rectangular window openings directly above these. In reviewing plans for the building, the Baltimore Sun wrote at the time that it would be one of the most prominent structures in that part of the city and continued, "Economy, durability and simplicity are the controlling motives of the design, and a practical power-house, with a proper regard for architectural proportions and effect, without unnecessary ornamentation, is expected to be the result."[5]

Additions were built in 1915-20 and 1949. It is also connected to a one-story brick building built in the 1960s. The second building complex is a 33,504-square-foot (3,112.6 m2) brick warehouse structure built from 1923 to 1927.

The architect was Jackson C. Gott, a Baltimore-based architect who is survived by eight buildings listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[1] In the same year the Jonestown cable-car powerhouse was built, Gott also designed the currently named Charles Theatre building on North Charles Street, also for the Baltimore City Passenger Railway. It too served as a cable-car powerhouse, in this case for the BCPR's 2.2 mile Blue Line, which ran north-south, essentially along Charles Street, from South Street to 25th street. In the 1890s Gott further designed two other well-known extant Baltimore buildings: the Maryland Penitentiary, now the Metropolitan Transition Center (1894), and the Southern District Police Station at 28 E. Ostend St. (1896).

Cable-car powerhouse

As a cable-car powerhouse for the Baltimore City Passenger Railway Company from 1892 to 1898, the building played an important role in Baltimore's transportation history as cable-car mass transit was developed to replace the horse-car. According to the Maryland Historical Trust, the building powered the run of cable from Gay Street to North Avenue, using two Reynolds compound non-condensing Corliss steam engines, 24" + 38" x 60". These propelled a sheave which pulled a continuous loop of cable and moved the car at a speed of around 11 MPH. Just like a subway line today, this line was designated by a color, the Red Line, and ran from North Avenue, down Gay Street, around to Baltimore Street, Bank Street and Patterson Park. The total mileage was 10.7.

Electric cars began replacing cable cars on the Red Line on August 30, 1898 as a more economical and faster means of mass transit. Cables were removed immediately, but the expense of extracting the underground pulleys, sheaves and other fittings was too much, and in most instances they were just covered over as streets were resurfaced. With the switchover, The Baltimore City Passenger Railway Company was absorbed into Baltimore's trolley monopoly, United Railways and Electric Company, and power was generated at the Pratt Street Power Plant. UREC held onto the building for a few years, using the rear half as a "trouble station" for trolleys and renting out the front to the US Navy (Maryland) Naval Reserves for use as a drill-room.

In all, the two Baltimore cable-car companies, Baltimore Traction Company (BTC) and Baltimore City Passenger Railway (BCPR), built six powerhouses, three each. This was a very significant capital expense for an enterprise that only lasted from 1891 to 1899. Of the three and a half surviving powerhouses, the Hendler Creamery is the only one listed on the National Register. As mentioned above, another Gott designed powerhouse survives today as the Charles Theatre (BCPR), while the third totally extant powerhouse (BTC) lies three blocks south at 1110 East Pratt Street. The latter was most recently used as the Pratt Street Garage of the Baltimore City Department of Solid Waste. It is now boarded up and waiting some kind of adaptive re-use. It stretches a full block, between East Pratt and Granby Streets, and is surrounded by Albemarle Square, a 15 block area that revitalizes both a public housing project and the surrounding neighborhood.[6]

While not having the architectural flair of Stanford White's nine-story Beaux-Arts Cable Building on in New York City, the Hendler Creamery is one of the absolute gems of the American cable powerhouses that have survived. For the most part these structures evidenced utilitarian, warehouse style construction, which can be seen clearly in the extant LaSalle Street Cable Car Powerhouse.

The only other architecturally significant Baltimore cable-car powerhouse, the former Baltimore Traction Company's Druid Hill Avenue powerhouse and car burn, lost half its structure in 2005 in a spectacular 5 alarm blaze. It is a massive Victorian Romanesque-style brick-and-stone structure.[7] The Epworth Powerhouse (BTC) on Mosher Street in West Baltimore had been torn down years before (see drawing below in gallery). It is a lesson in a site's metamorphoses: going from a church to a powerhouse to a dry cleaning plant, and finally, after demolition, to a high-rise apartment building today. The last powerhouse (BCPR) on South Eutaw, south of West Baltimore, succumbed long ago to the pressures of urban redevelopment.

Yiddish theatre

After the replacement of the cable car by electric trolleys, the Hendler Creamery was then converted into a performance space by Baltimore-born James Lawrence Kernan (1838-1912). He was a theater manager, entrepreneur, and philanthropist, who earlier in his life had fought for the Confederates, been captured and held as a prisoner till the war's end at the brutal Point Lookout Prisoner-of-War Camp at the confluence of the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River. Returning to civilian life, among other ventures, he started a combination hotel and German Rathskeller and founded a hospital, which survives today as the University of Maryland Rehabilitation & Orthopaedic Institute.

Under Kernan's ownership, a second floor, containing an auditorium and dressing rooms, was installed above the first-floor engine room. He named it the Convention Hall Theater. It operated primarily as a Yiddish theater from 1903 to 1912, serving the largely Jewish immigrant population. Some of the city's earliest motion pictures were also shown here by Kernan. Yiddish theater was first performed in Baltimore in the mid-1880s at Concordia Hall, an aristocratic club of Baltimore German Jews. It burnt down in 1891.

The building's conversion to a theater links it to Baltimore's early-20th century performing arts history, which includes melodrama, movies, opera, vaudeville, as well as the Yiddish theater.

Hendler Ice Cream Company

The building's most important and longest historical legacy came when it was purchased by the Hendler Ice Cream Company in 1912 for $40,000[8] and converted to the country's first fully automated ice cream factory.[2]

Besides producing one of Baltimore's favorite brands of ice cream, it played a major role in the development of the nation's ice cream business. Many important pioneering industry innovations were developed over the next 50 years in this building, including new kinds of packaging; the blade sharpener, which produced smoother ice cream; and fast freezing, which allowed ice cream to be frozen with a liquid cream texture. The adjoining building at 1107 East Fayette Street, built in the 1920s as part of the Hendler Creamery complex, is also significant, notably in the creation of one of the nation's first ice cream delivery systems by refrigerated truck. As the Maryland Historical Society noted in a blog posting, The Velvet Kind: The Sweet Story of Hendlers Creamery, "The ice cream was virtually everywhere in Maryland, as it was distributed to over 400 stores at the company’s peak, which kept the production lines humming. The factory ran six days a week with vanilla ice cream being made almost everyday. Vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry were production mainstays, but the creamery dabbled in more exotic flavors as well. Hutzler's department store sold several varieties, including ginger and peppermint. For the Southern Hotel,[9][10] Hendlers supplied a tomato sorbet which was served as a side dish rather than dessert. The eggnog ice cream was produced each year at Christmas time. Hendler made with real rum, was a major hit. The factory also cranked out other holiday-themed products, such as an Independence Day treat made with vanilla, strawberry, and blueberry ice creams and a Mother’s Day cake topped with a silk screen of James McNeill Whistler’s portrait of his mother."[11]

The creamery closed in the 1970s. The nearby Jewish Museum of Maryland has an extensive archive of Hendler Company and family memorabilia.[12]

Historic preservation designation

The Hendler Creamery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.[1]

Reuse

Following a fourth incarnation as a warehouse and city social services agency, the Hendler Creamery buildings are, as of the spring of 2014, being planned for refurbishment. The Commercial Group, a Maryland-based real estate and construction company, bought the building in 2012 for $1.08 million, and is planning a $45 million adaptive re-use, featuring 276 units, along with up to 11,000 sq ft of retail. The project includes exclusive amenities such as multiple outdoor courtyards, a pool deck overlooking the Baltimore skyline, basketball courts, and a yoga studio. Kirby Fowler, president of Downtown Partnership of Baltimore Inc., said redevelopment of the Hendler building would be the next chapter in a decade-long revival for Jonestown. “When you think about what that area used to be like 12 years ago, we’ve gone lightyears toward improvement,” Fowler said. “Albermarle Square [about four blocks away] is this incredibly progressive mixed-income project that came as the result of some HUD money and federal support, and it’s really helped expand Little Italy and Fells Point further north. There’s already progress heading in that direction, and this just continues that.”[13]

Baltimore City officials have said that they view this location—two blocks east of the iconic Shot Tower, seven blocks west of the bustling campus of The Johns Hopkins Hospital and nine blocks north of the contemporary mixed-use development project Harbor East—as critical to attractively tying together the Hopkins medical facilities and Downtown Baltimore.[14]

Gallery

- Front view.

- Front door detail.

- Medallion with man's head and the first two digits of year built -"18". Note the basket weave design of the brick pattern.

- Medallion with woman's head and second tow digits of the year built - "92"

Cable Driving Plant, Designed and Constructed by Poole & Hunt, Baltimore, MD. Drawing by P.F. Goist, circa 1882. The powerhouse has two horizontal single-cylinder engines. The lithograph shows a hypothetical prototype of a cable powerhouse, rather than any actual built structure.[15] Poole & Hunt, machinists and engineers, was a major cable industry designer and contractor and manufacturer of gearing, sheaves, shafting and wire rope drums. They did work for cable railways in Baltimore, Chicago, Hoboken, Kansas City, New York, and Philadelphia.[16]

Cable Driving Plant, Designed and Constructed by Poole & Hunt, Baltimore, MD. Drawing by P.F. Goist, circa 1882. The powerhouse has two horizontal single-cylinder engines. The lithograph shows a hypothetical prototype of a cable powerhouse, rather than any actual built structure.[15] Poole & Hunt, machinists and engineers, was a major cable industry designer and contractor and manufacturer of gearing, sheaves, shafting and wire rope drums. They did work for cable railways in Baltimore, Chicago, Hoboken, Kansas City, New York, and Philadelphia.[16]- A cable car wheel sheave, believed to be manufactured by Poole and Hunt of Baltimore, in Wheel Park in Otterbein, Baltimore. This was discovered under the streets during 1970s urban renewal. It would have been placed there in the 1890s. Such sheaving wheels could weigh between 15,000 and 30,000 pounds.

- Baltimore Traction Company installed a cable powerhouse in an old unused church in West Baltimore on Mosher Street. This was part of its Druid Hill Park to Patterson Park line. The site is now occupied by a high rise apartment building. The drawing by P.F. Goist gives a good sense of the cable equipment in the building and under the street.

- East Pratt Street Cable-Car Powerhouse in Baltimore—front view. Waiting for adaptive re-use. One of three Baltimore Powerhouses developed in the early 1890s by the Baltimore Traction Company.

- East Pratt Street Cable-Car Powerhouse in Baltimore—front entrance.

- East Pratt Street Cable-Car Powerhouse in Baltimore—rear view on Granby Street.

References

- 1 2 3 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 Charles Belfoure (January 2007). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Hendler Creamery" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ "Maryland Historical Society". Property Address file for 1100-1108 East Baltimore Street. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ The Benjamin Latrobe, Jr. Chapter of The Society for Industrial Archeology (1995). Baltimore: Industrial Gateway on the Chesapeake. Baltimore, MD.: The Baltimore Museum of Industry. p. Page 93.

- ↑ "Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. City Passenger Railway Power~House". The Baltimore sun. Feb 6, 1892. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ↑ Marc Wouters Architect and Urbanist. "Albemarle Square, Flag House Courts Revitalization". Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Jacques Kelly and Frederick N. Rasmussen (Jan 15, 2005). "Relic of cable cars is lost". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ↑ Ascher, Amalie (Jul 26, 1981). "ICE CREAM DAYS: Even Before Albert Hendler Started Working at the Plant He Got a Taste of the Business at Home". The Baltimore Sun.

- ↑ Updated for 2013. "Old Baltimore Hotels Kilduffs". The Southern Hotel -- 11 Light Street. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Frederick N. (June 5, 1999). "Way Back When Changes: Southern Hotel finally to fall -- Hotels have stood at the corner of Light and Redwood streets for more than 200 years. Another is to replace this one.". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ↑ Maryland Historical Society Library Department (July 18, 2013). "The Velvet Kind: The Sweet Story of Hendlers Creamery". underbelly FROM THE DEEPEST CORNERS OF THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ "MS 147 Hendler's Creamery Collection".

- ↑ Briggs, James (Nov 2, 2012). "Hendler Creamery building in southeast Baltimore sold for $1.08M Apartments planned for building in city's historic Jonestown". Baltimore Business Journal. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Litten, Kevin. "Kevin Litten". May 23, 2013. The Baltimore Business Journal. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ↑ Hilton, George W. (1971). The Cable Car in America, page 128. Berkeley, CA.: Howell NorthBooks.

- ↑ The Cable in Chicago: Speeding along the Streets Rapid Transit there for Miles (Nov 9, 1889). The Baltimore Sun, page 8. Missing or empty

|title=(help);

External links

- Hendler Creamery, Baltimore City, including photo from 2006, at Maryland Historical Trust