Isabella Furnace

|

Isabella Furnace | |

|

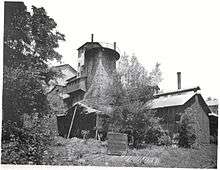

The furnace in ruins in 1959. | |

| |

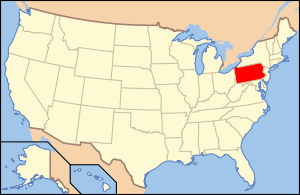

| Nearest city | Brandywine Manor, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°6′48″N 75°49′23″W / 40.11333°N 75.82306°WCoordinates: 40°6′48″N 75°49′23″W / 40.11333°N 75.82306°W |

| Area | 4 acres (1.6 ha) |

| Built | 1835 |

| Architectural style | Iron furnace |

| MPS | Iron and Steel Resources of Pennsylvania MPS |

| NRHP Reference # | 91001135[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 06, 1991 |

Isabella Furnace was a cold blast charcoal iron furnace located in West Nantmeal Township, Chester County, Pennsylvania. The furnace was named for Isabella Potts, wife of one of the partners, a member of the Potts ironmaking family. Isabella was the last iron furnace to be built in the county, in 1835, and was operated by members of the Potts family and their partners until 1855, when they lost control of it in a bankruptcy. It returned to the family in 1881, when it was purchased by Col. Joseph Potts (nephew of Isabella), who modernized it. The furnace, the last to operate in Chester County, went out of blast in 1894, a few months after Col. Potts' death, but remained largely intact until after his son's death in 1943. The remains of the furnace complex have been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since 1991.

History

The original operators of the furnace were Henry Potts and his brother-in-law (and second cousin) John Potts Rutter, who bought a tract of land from Robert Wilson on April 1, 1835 for the furnace site.[2]A[›] The land was along Perkins Run near where that stream emptied into the East Branch Brandywine Creek; the tract already included a fulling mill and a sawmill, and the transaction encompassed water rights to dam Perkins Run to power the furnace.[3] The Potts and Rutter families were already extensively involved in the iron business in the vicinity of Philadelphia; Henry's father Joseph was a partner in Glasgow Forge, on Manatawny Creek near Pottstown, Pennsylvania, and Henry was involved in ironmaking there and at Warwick Furnace, owned by his first cousin David Potts, Jr.[4] The furnace was completed by the end of the year and named in honor of Henry's wife Isabella, née Hitner. It proved to be the last sizable furnace erected in northern Chester County.[3][5]

In the spring of 1836, Henry's brother David, formerly the owner of Springton Forge, was brought in as a partner and manager of the furnace.[6] Henry retained a half interest and David and John each a quarter interest in Isabella Furnace. Ore from the furnace was obtained from the Jones and Warwick mines nearby; partners members of the allied Potts, Rutter, and Brooke families were among the partners in the mines.[7] In 1839 and 1840, respectively, Henry and David's brothers Robert Smith Potts and Joseph Potts were brought into the partnership. Ultimately, David bought out most of the family interest, except for a moiety held by his nephew, William A. Smith.[3] David's nephew Charles Follen McKim, later a noted architect, was born at Isabella in 1847. The furnace was well-run under David's direction, and in 1850, produced 1,000 short tons (910 t) of iron per year.[5] The furnace was converted to a forge in 1853. However, changing conditions in the iron market in the mid-1850s badly damaged David's financial position. Isabella Furnace was assigned to Robert Smith Potts and Addison May, who sold it in the following year to John Irey and James Butler.[3]

Irey was a carpenter who, like David Potts, had made iron at Springton Forge.[8] Under the new owners, the output of the forge in 1856 was 560 short tons (510 t) of blooms.[9] Irey bought out Butler in 1860 and thereafter operated the forge himself.[3] During the early years of the Civil War, the East Brandywine and Waynesburg Railroad built along the East Branch of the Brandywine on its way from Downingtown to Waynesburg, now Honey Brook. Its Wyebrooke station was about a half-mile south of the forge and provided a rail outlet for its products.[10] The forge was remodeled in 1864[11] and it was presumably then that it became a furnace again, but Irey's operations during the Civil War were not profitable.[3]

He sold out in 1865 to the brothers Bentley H., William D., and Horace V. Smith, members of an ironmaking family associated with Joanna Furnace and the mines around Warwick.B[›] William D. and Horace V. Smith were particularly associated with the management of the furnace until 1881. About 1870, as the Wilmington and Reading Railroad built through the region on the way from Wilmington, Delaware to Birdsboro, Pennsylvania, it established a station called "Isabella" about a mile northwest of the furnace.[10]

In 1880, a new figure appeared upon the scene: Col. Joseph D. Potts (1829–1893), son of David Potts. Raised at Isabella Furnace, he regarded it as home. Potts made a fortune in the railroad and transportation industry, in the employ of the Pennsylvania Railroad and elsewhere. When he retired from that business, he desired to return to the property where he had been raised and become an ironmaster, like so many of his family before him. He won over the Smith brothers, who were reluctant to sell, and closed on the property on February 28, 1880.[12]

Potts was willing to make substantial investments in modernizing the furnace. His improvements included conversion from water to the more reliable steam power for creating the furnace blast. Potts also arranged for the construction of a spur line to the furnace from the East Brandywine and Waynesburg, which had come under the control of the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1876. This facilitated the shipment of raw materials to, and iron from, the furnace; in 1884, Isabella was reported to be using a combination of the local ores and imported Spanish ore to produce "car-wheel" pig iron, sold under the "Wyebrooke" brand.C[›] At this time, the annual capacity of the furnace had increased to 3,000 short tons (2,700 t) of iron[11] due to the modernization. Soon after buying the furnace, Col. Potts appointed his elder son, William M. Potts, manager of the furnace; William's younger brother, Francis L. Potts, was also associated with Isabella until 1886.[13] In that year, Isabella underwent its last rebuilding. By 1892, the furnace was using a blend of local ores, ore from Lancaster County, Elba, and Lake Superior, and reported an annual capacity of 6,000 short tons (5,400 t).[14]

In 1891, Col. Potts began building a nearby chateau-like mansion, "Langoma" (1891–95, Theophilus P. Chandler, Jr., architect),[15] which he intended as a residence for himself and his son William.[16] However, he died in December 1893 and did not live to see it completed. William, his wife, and mother did move into "Langoma", but ironmaking at the furnace ended in April 1894, not long after Col. Potts' death. It was the last iron furnace operating in Chester County.[3] The furnace and railroad spur were left largely intact, although unused. The slow dilapidation of the furnace produced a remarkable aesthetic effect. Henry Seidel Canby referred in 1935 to "its moldering cupola furnace, like a Persian mosque of the twelfth century, its long walls and sleepy half-drained dam."[17] This slow decay was accelerated after the death of William M. Potts in 1943, when the railroad was taken up and other metal was reclaimed for scrap. Even after this, HABS photographer Ned Goode said of the furnace in 1959 that "its wild setting in an over-grown field is quite striking".[3]

After the death of William Potts, the ruined furnace was sold by his estate to Frank Bloise, who sold it in 1945 to Langoma Industries,[3] a clothing firm with which Bloise was involved. Langoma Industries intended to set up a clothing factory and a surrounding worker's town on the Potts estate.[18] It was still owned by Langoma Industries in 1959.[3] Ultimately, the property was converted to a private residence by Dr. and Mrs. Daniel Leiberman, who sold the property about 1983.[19]

Buildings

The original stack of the furnace was 33 feet (10 m) high, with a 6.5-foot (2.0 m) bosh. Either the 1864 or 1881 remodeling increased the height to 35 feet (11 m), with a 7.75-foot (2.36 m) bosh. The last remodeling, in 1886, enlarged the stack to 60 feet (18 m).[5]

A Hexamer General Survey plan of the furnace made in 1890 shows a number of structures arranged along the hillside sloping down to Perkins Run. Atop the hillside were a "coalhouse", "orehouse", and "screenhouse"; three large warehouses (about 100' x 50' each) with railroad trestles running into them for the delivery and storage of raw materials. Their elevated position allowed charcoal and ore to be moved directly to a crusher house and a charging house on the edge of the hillside; the mixed coal and ore could then move across a charging bridge into the top of the furnace stack, whose base was at the foot of the hill. Attached to the base of the furnace were a "wheel house", apparently used for storing casting sand and fire brick, and a casting house where molten iron from the furnace could run into molds. Just to the northwest lay the boiler shed and blowing engine for the furnace's steam-powered tuyeres, and several ancillary buildings also lay in the floodplain on both sides of Perkins Run.

Current aerial photography shows the coalhouse, casting and crushing houses, blowing engine house, and a small storage building have been reroofed and appear to form part of a private residence. The furnace stack appears to be largely demolished, and other buildings are gone; the foundations and lower walls of the orehouse and screenhouse are still evident.

Notes

- ^ A: Other sources date the construction to about 1830 or 1834, but the land sale to Potts and Rutter did not occur until 1835.

- ^ B: The Smith ironmasters of Joanna Furnace do not appear to be connected with William A. Smith.

- ^ C: The low-silicon cast iron required for railroad car wheels was more easily made at the lower-temperature charcoal iron furnaces than those fired with coke or anthracite.[20]

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Diane B. Reed, 1991, NRHP Nomination Form for Isabella Furnace

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Historic American Buildings Survey, No. PA-163.

- ↑ Moses Auge (1879). Lives of the eminent dead: and biographical notices of prominent living citizens of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Norristown, Pennsylvania. pp. 200–201.

- 1 2 3 Carroll W. Pursell (1957). The Manufacture of Iron in the Christina-Brandywine Valley, 1720-1900. Hagley Museum and Library. pp. 26, 114.

- ↑ Mrs. Thomas Potts James (1874). Memorial of Thomas Potts, Junior. p. 294.

- ↑ J.H. Harden (1886-10-16). "Early Mining Operations in Berks and Chester Counties". Proceedings of the Engineers' Club of Philadelphia. VI: 23–35.

- ↑ George W. Wagenseller (1898). The history of the Wagenseller family in America. Middleburgh, Pennsylvania: Wagenseller Publishing Company. pp. 65–66.

- ↑ J. Peter Lesley (1859). The iron manufacturer's guide to the furnaces, forges and rolling mills of the United States. New York: John Wiley. p. 165.

- 1 2 Taber, Thomas T., III (1987). Railroads of Pennsylvania Encyclopedia and Atlas. Thomas T. Taber III. pp. 398, 474. ISBN 0-9603398-5-X.

- 1 2 The American Iron and Steel Association (1884). Directory to the Iron and Steel Works of the United States. 7. Philadelphia: Allen, Lane & Scott. pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Cyrus T. Fox (October 15, 1916). "Luck Favors Col. Joseph D. Potts; Returns to Scenes of His Youth". Reading Eagle.

- ↑ Lloyd, Mark Frazier (August 2000). "A Brief History of the "Carriage House" at the Rear of 3905 Spruce Street". Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ↑ The American Iron and Steel Association (1892). Directory to the Iron and Steel Works of the United States. 11. Philadelphia: Allen, Lane & Scott. p. 32.

- ↑ Potts residence, from Philadelphia Architects and Buildings.

- ↑ Langoma Estate, from Facebook.

- ↑ Henry Seidel Canby (1969). The Brandywine. Exton, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Limited. p. 233. ISBN 0-916838-06-4.

- ↑ "New Industries to Provide Jobs in Post-War Era". The Clinton County Times. March 29, 1945.

- ↑ "Castle was a Furnace". Philadelphia Inquirer. March 6, 1983.

- ↑ Robert B. Gordon (1996). American Iron 1607–1900. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-8018-6816-5.

Further reading

- Hagley Digital Archives, American Iron and Steel Institute photograph collection (several photographs before and after abandonment)

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Forges and Furnaces Collection (#212) (various records 1871–1921)

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania, William McCleary Potts Collection (#1401) (correspondence of the last manager)

- Pennsylvania State Archives, Photograph Collection MG-218 (one photograph)

External links

Media related to Isabella Furnace at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Isabella Furnace at Wikimedia Commons- Hexamer Survey showing plan of Isabella Furnace in 1890.