Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan

Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan جماعتِ اسلامی | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ameer | Siraj ul Haq[1] |

| General Secretary | Liaqat Baloch |

| Naib Ameer |

Khurshid Ahmed, Mian Muhammad Aslam, Rashid Naseem, Asad ullah Bhutto, Hafiz Muhammad Idress , Professor Muhammad Ibrahim , Dr. Fareed Ahmed Paracha . |

| Provincial Ameer |

Dr.Meraj ul Huda Siddiqui (Sindh), Mushtaq Ahmed Khan (KPK), Mian Maqsood Ahmed (Punjab), Molana Abdul Haq Hashmi (Balochistan). |

| Founder | Sayyid Abul A'la Maududi |

| Founded | 26 August 1941 |

| Headquarters | Mansoorah, Lahore, Pakistan |

| Ideology |

Islamism Islamic democracy |

| Political position | Right-wing |

| International affiliation |

Jamaat-e-Islami Hind Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami Muslim Brotherhood |

| Colors | Green, white, blue |

| Senate |

1 / 104 |

| National Assembly |

4 / 342 |

| Punjab Assembly |

1 / 371 |

| Pakhtunkhwa Assembly |

7 / 124 |

| Election symbol | |

| Scale | |

| Website | |

|

www | |

Jamaat-e-Islami (Urdu: جماعتِ اسلامی, JI) is a social conservative, and Islamist political party. Its objective is to make Pakistan an Islamic state, governed by Sharia law, through a gradual legal, and political process.[2] JI strongly opposes capitalism, liberalism, socialism and secularism as well as economic practices such as offering bank interest. JI is a vanguard party: its members form an elite with "affiliates" and then "sympathizers" beneath them. The party leader is called an ameer.[3](p70) Although it does not have a large popular following, the party is quite influential and considered one of the major Islamic movements in Pakistan, along with Deobandi and Barelvi.[4]

JI came to its modern foundation in Lahore in 1941 in British India by the Muslim theologian and socio-political philosopher, Abul Ala Maududi.[5] In 1947, JI moved its operations to West Pakistan after independence.[6](p223) Members who remained in India formed an independent organisation, Jamaat-e-Islami Hind.

The party came under severe government repression in 1948, 1953, and 1963,[7] but during the early years of the regime of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq served as the "regime's ideological and political arm",[8] with party members holding cabinet portfolios of information and broadcasting, production, and water, power and natural resources.[9]

In 1971, during the Bangladesh Liberation War, JI opposed the independence of Bangladesh and its members participated in the genocide on Bengali people led by the Pakistan Army.[10][11] However, in 1975, it established a new branch, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami in the new nation. Abbas Ali Khan (Joypurhat) was the founder & first Ameer of Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami. Other offshoots of Jamaat-e-Islami, (which split into separate independent organizations following the Partition of India in 1947) include Jamaat-e-Islami Hind in India, and Jamaat-e-Islami Kashmir in Jammu & Kashmir. The JI maintains close ties with these and other international Muslim groups.[12]

History

| Growth of JIP[13] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Members (Arkan) |

Sympathizers and workers (Hum-Khayal) |

| 1941 | 75 | (unknown) |

| 1951 | 659 | 2913 |

| 1989 | 5723 | 305,792 |

| 2003 | 16,033 | 4.5 million |

| SOURCE: Encyclopedia of Islam & the Muslim World (2004)[13] | ||

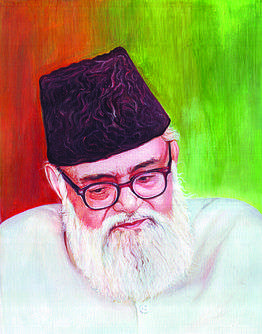

Syed Abul A'la Maududi (1940 - 1979)

Jamaat-e-Islami's founder and leader until 1972, was Abul A'la Maududi, a widely read Islamist philosopher and political commentator, who wrote about the role of Islam in South Asia.[14] His thought was influenced by many factors including the Khilafat Movement; Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's ascension at the end of the Ottoman Caliphate; and the impact of Indian Nationalism, the Indian National Congress and the Hinduism on Muslims in India. He supported what he called "Islamization from above", through an Islamic state in which sovereignty would be exercised in the name of Allah and Islamic law (sharia) would be implemented. Mawdudi believed politics was "an integral, inseparable part of the Islamic faith, and that the Islamic state that Muslim political action seeks to build" would not only be an act of piety but would also solve the many (seemingly non-religious) social and economic problems that Muslims faced.[14][15]

Maududi opposed British rule but also opposed the Muslim nationalist movement (nationalism being un-Islamic) and (at first) their plan for a circumscribed "Muslim state". Maududi agitating instead for an "Islamic state" covering the whole of India[14]—this despite the fact Muslims made up only about one quarter of India's population.

In 1940, at the time of the Pakistan Resolution, Maududi taught that Pakistan was destined to be an Islamic missionary nation. This was in comparison to scholars of the Indian Congress who promoted the formation of a sub-continent united against British rule. To Maududi, a united sub-continent would be worse than British rule. He likened the Congress to Robert Clive, and Arthur Wellesley, and Muslim followers of the Congress to collaborators like Mir Jafar and Mir Sadiq. He compared nationalism and communism to the Shuddhi movement. Maududi criticised Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, alleging that he opposed religion, was an enemy of any division on basis of faith and planned to merge Islam into the Hindu faith.

Maududi also criticised the nationalist, Husain Ahmad Madani for promoting unity through a combined governance and justice system or a majority based political system. The Joint Secretary of the All India Muslim League and expert in constitutional law and Islam, Zafar Ahmed Ansari, supported Maududi's stance.

Founding of JI

Jamaat-e-Islami was founded on 26 August 1941, at Islamia Park, Lahore,[6](pli) before the Partition of India. JI began as a Islamist social and political movement. Seventy-five people attended the first meeting and became the first 75 members of the movement.

Maududi saw his group as a vanguard of Islamic revolution following the footsteps of early Muslims who gathered in Medina to found an Islamic state.[14][15] JI was and is strictly and hierarchically organized in a pyramid-like structure, working toward the common goal of establishing an ideological Islamic society, particularly though educational and social work, under the leadership of its emirs (commanders or leaders).[13] As a vanguard party, its fully-fledged members (arkan) are intended to be leaders and devoted to the party, but there is also a category of much more numerous sympathizers and workers (karkun).

The emir is obliged by the party constitution to consult an assembly called the shura. The JI also developed sub-organizations, such as those for women and students.[13] JI began by volunteering in refugee camps; performing social work; opening hospitals and medical clinics and by gathering the skins of animals sacrificed for Eid-ul-Azha.

JI had a number of unique features. All members, including its founder Mawdudi, uttered the shahadah—the traditional act of converts to Islam—when they joined. This was a symbolic gesture of conversion to an new Islamic Perspective, but to some implied that "the Jamaat stood before Muslim society as Islam before jahiliyah", (pre-Islamic ignorance).[16] After Pakistan was formed, it forbade Pakistanis to take an oath of allegiance to the state until it became Islamic, arguing that a Muslim could in clear conscience render allegiance only to God.[17][18]

Pakistan

- Creation and early years

Following the Partition of India, Maududi and JI migrated from East Punjab to Lahore in Pakistan. There they volunteered to help the thousands of refugees pouring into the country from India[19]—performing social work; opening hospitals and medical clinics; and by gathering the skins of animals sacrificed for Eid-ul-Azha.

During the prime-ministership of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy (July 1946 - August 1947), JI argued for a separate voting system for different religious communities. Suhrawardy convened a session of the National Assembly at Dhaka and through an alliance with Republicans, his party passed a bill for a mixed voting system.

In 1951 it ran candidates for office but did not do well. JI found it was more successful in promoting its cause in the streets.[20] The election also occasioned a split in the party with the JI shura passing a resolution in support of the party withdrawing from politics but Maududi arguing for continued involvement. Maududi prevailed and several senior JI leaders resigned in protest. All this strengthened Maududi's position still further and "a cult of personality began to grow up around him."[20]

In 1953, JI led "direct action" against the Ahmadiyya, who the JI believed should be declared non-Muslims. In March 1953 riots in Lahore started leading to looting, arson and the killing of at least 200 Ahmadis and the declaration of selective martial law. The military leader, Azam Khan had Maududi arrested and Rahimuddin Khan sentenced him to death for sedition (writing anti-Ahmadiyya pamphlets).Many JI supporters were imprisoned during this time.

The 1956 Constitution was adopted after accommodating many of the demands of the JI. Maududi endorsed the constitution and claimed it a victory for Islam.[21] In 1958, JI formed an alliance with Abdul Qayyum Khan (Muslim League) and Chudhary Muhammad Ali (Nizam-e-Islami party). The alliance destabilised the presidency of Iskander Mirza (1956 - 1958) and Pakistan returned to martial law. The military ruler, the president Muhammad Ayub Khan (1958 - 1964), had a modernizing agenda and opposed the encroachment of religion into politics. He banned political parties and warned Maududi against continued religio-political activism. JI offices were closed down, funds were confiscated and Maududi was imprisoned in 1964 and 1967.[21]

JI supported the opposition party, the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM). In the 1964 - 1965 presidential elections, JI supported the opposition leader, Fatima Jinnah, despite its opposition to women in politics.[21]

In 1965, during the Indo-Pakistani war, JI supported the government's call for jihad, presenting patriotic speeches on Radio Pakistan and seeking support from Arab and Central Asian countries. The group resisted Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Maulana Bhashani's socialist program of the time.

By the end of 1969, the Jamaat-e-Islami was spearheading a major “campaign for the protection of ideology of Pakistan,” which it believed was under threat from atheistic socialists and secularists.[22]

JI participated in the 1970 general election. Its political platform advocated political freedom of the provinces and Islamic law based on the Quran and Sunnah. There would be separation of the powers (judiciary and legislature); basic rights for minorities (such as equal employment opportunities and the Bonus Share Scheme allowing factory workers to own shares in their employers' companies); and a policy of strong relationships with the Muslim world. Just prior to the election, Nawabzada Nasrullah Khan left the alliance leaving JI to run against the Pakistan Peoples Party and the Awami League. The party had a disappointing showing when it won only four seats in the national assembly and four in the provincial assembly after fielding 151 candidates.[23]

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto won the 1970 election campaign and was strongly opposed by JI who believed he and his socialist ideology were a threat to Islam.[24]

- Division

JI opposed the Awami League East Pakistani separatist movement.[25] Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba organised the Al-Badar to fight the Mukti Bahini (Bengali liberation forces). In 1971, during the Bangladesh liberation war, JI members may have collaborated with the Pakistani army in the killing and raping of Bengali civilians.[26][27][28]

In 1972, Maududi resigned citing poor health. In October 1972, the Majlis-e-Shoura (council) elected Mian Tufail Mohammad (1914 - 2009), the new leader of JI.

Mian Tufail Mohammad (1972 - 1987)

After Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (1973 - 1977) was elected, the student wing of the Jamaat-e-Islami (Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba) burned effigies of him in Lahore and declared his election a “black day.” In early 1973, the amir, of the JI even appealed to the army to overthrow Bhutto’s government because of “its inherent moral corruption.”[29]

JI "spearheaded" the anti-Bhutto political movement under the religious banner of Nizam-i-Mustafa (Order of the Prophet). Bhutto attempted to suppress JI through the imprisonment of JI and Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba members. There were electoral irregularities at the 1975 elections with JI members being arrested in order to prevent them from lodging their nomination papers.[30] However, by 1976, JI had 2 million registrants.

In the 1977 JI won nine of the 36 seats won by the opposition Pakistan National Alliance. The opposition considered the election rigged (Bhutto's PPP won 155 out of 200 seats) and Maududi, who had been arrested, called on Islamist parties to commence a campaign of civil disobedience. The Sunni led government of Saudi Arabia intervened to secure Maududi's release from prison warning of revolution in Pakistan. JI assisted the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) to oust Bhutto and met with Zia-ul-Haq for ninety minutes on the night before Bhutto was hanged.[31]

Initially, JI supported General Zia-ul-Haq (1977 - 1987).[32] In turn, Zia's use of Islamist rhetoric gave JI importance in public life beyond the size of its membership.[33] According to journalist Owen Bennett Jones, JI was the "only political party" to offer Zia "consistent support" and was rewarded with jobs for "tens of thousands of Jamaat activists and sympathisers", giving Zia's Islamic agenda power "long after he died."[34]

However, Zia failed to deliver timely elections and distanced himself from the JI. When Zia banned student unions, Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba and pro-JI labor unions protested. However, JI did not participate in the Pakistan Peoples Party's Movement for the Restoration of Democracy. JI also supported Zia's Jihad against the Soviet War in Afghanistan and its sister party Jamiat-e Islami led by Burhanuddin Rabbani became part of the Peshawar Seven that received aid from Saudi Arabia, United States and other jihad supporters.[6](p272) Such conundrums caused tension in JI based on conflict between ideology and politics.[33][35]

In 1987, Mian Tufail declined further service as head of JI for health reasons and Qazi Hussain Ahmad was elected.

Qazi Hussain Ahmad (1987 - 2008)

In 1987, when Zia died, the Pakistan Muslim League formed the right-wing alliance, Islami Jamhoori Ittehad (IJI).[33](p180) In 1990 when Nawaz Sharif came to power, JI boycotted the cabinet on the basis that the Pakistan Peoples' Party and the Pakistan Muslim League were problematic to equal degrees.

In the election of 1993, JI won three seats. In this year, JI was a member of the newly formed All Parties Hurriyat Conference (APHC) which promotes the independence of Jammu and Kashmir from India.[6](p26) Prior to this, JI had allegedly set up the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, a Kashmir liberation militia to oppose the Kashmir Liberation Front which fights for the complete independence of the Kashmir region.[6](p127)

Ahmad left his position in the Senate in protest against corruption.

Successful Long March Against Bhutto's Government

On 20 July 1996, Qazi Hussain Ahmed announced to start protests against government alleging corruption. Qazi Hussain resigned from senate on 27 September and announced to start long march against Benazir government. Protest started on 27 October 1996 by Jamaat e Islami and opposition parties. On 4 November 1996, Bhutto's government was dismissed by President Leghari primarily because of corruption.[3] JI then boycotted the 1997 election and therefore lost representation in parliament. However, the party remained politically active, for example, protesting the arrival of the Indian prime minister, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, in Lahore.

In 1999, Pervez Musharraf took power in a military coup. JI, at first, welcomed the general but then objected when Musharraf began to make secular reforms and then again in 2001, when Pakistan joined War on terrorism, alleging Musharraf had betrayed the Taliban. JI condemned the events of 11 September 2001 but equally condemned the US when Afghanistan was entered.[3](p69) Some members of Al Quaida, for example, Khalid Sheik Mohammed, were arrested in Pakistan in homes owned by supporters of JI.[36][37]

In 2002, JI made an alliance of religious parties called Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) (United Council of Action) and won 53 seats, including most of those representing the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province.[6] JI continued its opposition to the War on terrorism, particularly the presence of American troops and agencies in Pakistan. JI also called for restoration of judiciary.

Qazi Hussain Ahmad gave his resignation from the National Assembly when visiting the camp of victims of an attack in Lal Masjid.

In 2006, JI opposed the Women's Protection Bill saying it did not need to be scrapped but instead, be applied in a fairer way and more and be more clearly understood by judges. Ahmed said,

- "Those who oppose [these] laws are only trying to run away from Islam...These laws do not affect women adversely. Our system wants to protect women from unnecessary worry and save them the trouble of appearing in court."[38]

Samia Raheel Qazi, MP and daughter of Ahmed stated,

- "We have been against the bill from the start. The Hudood Ordinance was devised by a highly qualified group of Ulema, and is beyond question".

At least during the time of Ahmad, the position of JI on revolutionary action was that it was not ready to turn to extra-legal action but that its objectives are definite (qat'i) but its methods are "open to interpretation and adaptation (ijtihadi)" based on the "exigencies of the moment".[39]

Sayyed Munawer Hassan (2008 - 2014)

In 2008, JI and Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf again boycotted the elections. Ahmad declined reelection and Syed Munawar Hassan became ameer.

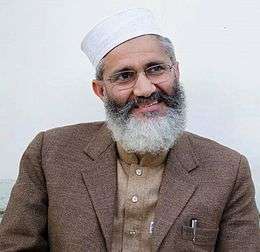

Siraj ul Haq (2014–present)

On 30 March 2014, Siraj ul Haq became ameer.[1] He resigned from his role as senior minister of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province. This coincided with a drone attack on Madrassa, Bajour Agency.

Organizations

JI provides unions for doctors, teachers, lawyers, farmers, workers and women, for example, Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba (IJT) and Islami Jamaat-e-Talibaat (its female branch)[6](p181) a Students' union and Shabab e Milli, a youth group.

The party has a number of publications from affiliated agencies such as Idara Marif-e-Islami, Lahore, the Islamic Research Academy, Karachi, Idara Taleemi Tehqeeq, Lahore, the Mehran Academy, and the Institute of Regional Studies.

The "Islami Nizamat-e-Taleem" led by Abdul Ghafoor Ahmed, is an educational body that includes 63 Baithak schools. Rabita-ul-Madaris Al-Islamia supports 164 JI Madrasas. JI also operates the "Hira Schools (Pakistan) Project" and "Al Ghazali Trust". The Al-Khidmat Foundation is JI's humanitarian NGO. Its predecessor, organised in the mid 1990s was the Al-Khidmat Trust. The foundation administers schools, women's vocational centres, adult literacy programs, hospitals and mobile chemists and other welfare programs. In this respect, JI interacts with the general market.[33](p480)

Connections with insurgents

Jama'ati is said to have close links to many banned outfits of Pakistan. The most notable connection is with the Tehreek-e-Nafaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi. This militant organization grew as an offshoot of Jammat e Islami and was founded by Sufi Muhammad in 1992 after he left Jamaat-e-Islami.[40][41][42] When the founder was imprisoned on January 15, 2002, Maulana Fazlullah, his son-in-law, assumed leadership of the group. In the aftermath of the 2007 siege of Lal Masjid, Fazlullah's forces and Baitullah Mehsud's Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) formed an alliance. Fazlullah and his army reportedly received orders from Mehsud.[43] After the death of Hakimullah Mehsud in a drone attack, Fazlullah was appointed as the new "Amir" (Chief) of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan on 7 November 2013.[44][45][46] In a May 2010 interview, U.S. Gen. David Petraeus described the TTP's relationship with other militant groups as difficult to decipher: "There is clearly a symbiotic relationship between all of these different organizations: al-Qaeda, the Pakistani Taliban, the Afghan Taliban, TNSM [Tehreek-e-Nafaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi]. And it's very difficult to parse and to try to distinguish between them. They support each other, they coordinate with each other, sometimes they compete with each other, [and] sometimes they even fight each other. But at the end of the day, there is quite a relationship between them." [45][47]

According to another source, TNSM and Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) seem to have been locked in a turf war in the Malakand District of Pakistan, and the Jamaat-Ulema-e-Islam, JI, and TNSM are in conflict with each other in the tribal areas for power and influence.[48]

Leaders

- Abul A'la Maududi (1940 - 1972)

- Mian Tufail Mohammad (1972 - 1987)

- Qazi Hussain Ahmad (1987 - 2008)

- Syed Munawar Hassan (2008 - 2014)

- Siraj ul Haq (2014–present)

- Khurram Murad

- Liaqat Baloch

- Khurshid Ahmad (Islamic scholar)

- Mohammad Kamal

- Huzaifa Zafar

See also

- Israr Ahmed

- Sayed Ahmad Khan

- Amin Ahsan Islahi

- Allamah Delwar Hossain Sayeedi

- Abdul Qader Molla

- Motiur Rahman Nizami

References

- 1 2 "Sirajul Haq replaces Munawar Hassan as chief of Jamaat-e-Islami". The Express Tribune. 30 March 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.122

- 1 2 3 Adel G. H. et al (eds.) "Muslim Organisations in the Twentieth Century: Selected Entries from Encyclopaedia of the World of Islam." EWI Press, 2012 p.67 ISBN 1908433094, 9781908433091.

- ↑ Roy, Olivier (1994). The Failure of Political Islam. Harvard University Press. p. 88.

Islam in Pakistan is divided into three tendencies: the Jamaat, which is the Islamist party and which, although it does not have extensive popular roots, is politically influential; the deobandi, administered by fundamentalists and reformist ulamas; and the Barelvi, which recruits from popular and Sufi Islamic circles.

- ↑ van der Veer P. and Munshi S. (eds.) "Media, War, and Terrorism: Responses from the Middle East and Asia." Psychology Press, 2004 p138. ISBN 0415331404, 9780415331401.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Guidere M. "Historical Dictionary of Islamic Fundamentalism." Scarecrow Press, 2012 p356 ISBN 0810879654, 9780810879652.

- ↑ Nasr, Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism, 1996: p.97

- ↑ Kepel, Jihad, (2002), pp.98, 100, 101

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.138

- ↑ Schmid 2011, p. 600.

- ↑ Tomsen 2011, p. 240.

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.171

- 1 2 3 4 Encyclopedia of Islam & the Muslim World| By Richard C. Martín| Granite Hill Publishers|2004|p.371

- 1 2 3 4 Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad: on the Trail of Political Islam. Belknap Press. p. 34. ISBN 9781845112578.

- 1 2 Nasr, S.V.R. (1994). The Vanguard of the Islamic Revolution: the Jamaat-i Islami of Pakistan. I.B.Tauris. p. 7.

- ↑ Nasr, Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr (1996). Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 110.

All members, including Mawdudi, uttered the shahadah when they joined, in a symbolic gesture of conversion to an new Islamic Perspective

- ↑ Nasr, Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism, 1996: p.42

- ↑ Nasr, Vanguard of the Islamic Revolution, 1994, pp.119-120

- ↑ Adams, Charles J., "Mawdudi and the Islamic State," in John L. Esposito, ed., Voices of Resurgent Islam, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983, p.102)

- 1 2 Nasr, Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism, 1996: p.43

- 1 2 3 Nasr, Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism, 1996: p.44

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.46

- ↑ Nasr, Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism, 1996: p.45

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.69

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.100

- ↑ Arefin S. "Muktijuddho '71: Punished War Criminals Under Dalal Law." Bangladesh Research and Publications.

- ↑ Bangladesh Genocide Archive website. Accessed 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Nabi N. "Bullets of '71: A Freedom Fighter's Story." AuthorHouse, 2010 p.108 ISBN 1452043833, 9781452043838.

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.96

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.120

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.139

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.123

- 1 2 3 4 Osella F. and Osella C. "Islamic Reform in South Asia." Cambridge University Press, 2013 p479. ISBN 1107031753, 9781107031753.

- ↑ Jones, Owen Bennett (2002). Pakistan : eye of the storm. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 16–7.

... Zia rewarded the only political party to offer him consistent support, Jamaat-e-Islami. Tens of thousands of Jamaat activists and sympathisers were given jobs in the judiciary, the civil service and other state institutions. These appointments meant Zia's Islamic agenda lived on long after he died.

- ↑ Kepel, Gilles (2002). Jihad: on the Trail of Political Islam. Belknap Press. p. 104. ISBN 9781845112578.

- ↑ Gannon K. "I Is for Infidel: From Holy War to Holy Terror in Afghanistan." PublicAffairs, 2006 p.158 ISBN 1586484524, 9781586484521.

- ↑ Spencer R. "Onward Muslim Soldiers: How Jihad Still Threatens America and the West." Regnery Publishing, 2003 p.244 ISBN 0895261006, 9780895261007.

- ↑ Haqqani, Pakistan, 2005: p.145

- ↑ Based on interviews with a number of JI leaders, especially Khalil Ahmadu'l-Hamidi by Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr, (in Nasr, Maududi and the making of Islamic Revivalism, p.76)

- ↑ "Tehreek-e-Nafaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (Movement for the Enforcement of Islamic Laws)". South Asia Terrorism Portal. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ↑ Jan, Delawar (2009-02-17). "Nizam-e-Adl Regulation for Malakand, Kohistan announced". The News International. Archived from the original on 16 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ↑ Nasir, Sohail Abdul (2006-05-17). "Religious Organization TNSM Re-Emerges in Pakistan". Terrorism Focus. 3 (19). The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ↑ Rehmat, Kamran (2009-01-27). "Swat: Pakistan's lost paradise". Islamabad: Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2009-02-03.

- ↑ Mujtaba, Haji (7 November 2013). "No more peace talks, 'Mullah Radio' tells Pakistan". Reuters. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- 1 2 Bajoria, Jayshree (6 February 2008). "Pakistan's New Generation of Terrorists". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 30 March 2009.

- ↑ Hassan Abbas (12 April 2006). "The Black-Turbaned Brigade: The Rise of TNSM in Pakistan". Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ↑ Carlotta Gall, Ismail Khan, Pir Zubair Shah and Taimoor Shah (26 March 2009). "Pakistani and Afghan Taliban Unify in Face of U.S. Influx". New York Times. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ↑ "Tehreek Nifaz-e-Shariat Mohammadi". Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

Bibliography

- Schmid, Alex, ed. (2011). The Routledge Handbook of Terrorism Research. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-41157-8.

- Tomsen, Peter (2011). The Wars of Afghanistan: Messianic Terrorism, Tribal Conflicts, and the Failures of Great Powers. Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-763-8.

- Nasr, Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr (1996). Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Haqqani, Husain (2005). Pakistan: Between Mosque and Military (PDF). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 46.

External links

- Official website (English)

- Profile: Jamaat-e-Islami & Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi GlobalSecurity.org

- Bangladesh ruling party expels MP BBC, 25 November 2005

- Pakistan rulers claim poll boost BBC, 7 October 2005

- Who's afraid of the six-party alliance? BBC, 17 August 2005

- Pakistan 'hate' paper crackdown BBC, 16 August 2005

- Radical links of UK's 'moderate' Muslim group Martin Bright, The Observer, 14 August 2005

- Congressional Report: The New Islamist International(from FAS site) Bill McCollum, US Congressional Task Force on Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare, 1 February 1993.

- Tanzeem-e-Islami (Tehreek-e-Khilafah)