Long Branch Plantation

|

Long Branch Plantation | |

|

Long Branch House | |

| |

| Location | W of jct. of CR 626 and 624, Millwood, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°2′34″N 78°3′21″W / 39.04278°N 78.05583°WCoordinates: 39°2′34″N 78°3′21″W / 39.04278°N 78.05583°W |

| Area | 400 acres (160 ha) |

| Built | 1811 |

| Architect | unknown, Latrobe, Benjamin |

| Architectural style | Federal, Greek Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 69000232[1] |

| VLR # | 021-0095 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 01, 1969 |

| Designated VLR | November 5, 1968[2] |

Long Branch Plantation is a historic family seat in Millwood, Virginia built in the early 19th century; named after the creek that runs through the property. Built on approximately 1000 acres (currently 400 acres) by Robert Carter Burwell in 1811 and owned by the Burwell-Nelson family until 1957. The property was placed on the National Register on October 1, 1969.

History

On September 18, 1650, Charles II of England, granted the original tract of the Northern Neck of Virginia, to seven followers including Lord Culpepper. On September 7, 1688, after acquiring the interests of the remaining grantees, Lord Culpepper was recognized as the sole owner of the Northern Neck. This land passed to his grandson Thomas, 6th Lord of Fairfax and was managed by him until his death in 1781.

Robert Carter, familiarly known as “King Carter” was appointed agent for the sale and lease of unoccupied areas of the Fairfax proprietary. On September 22, 1730, acting as Fairfax’s agent, he executed a deed to ten of his sons and grandsons: 50,212 acres of land in what are now Clarke, Warren, and Frederick Counties, Virginia. In 1740 the land was split into eight lots and divided into approximately the same size lots.[3] Robert “Robin” Burwell, a grandson to King Carter, received 5,619 acres of the land. Robert “Robin” Burwell left his land to his son Nathaniel and to his grandson Robert Carter Burwell. In 1769, Robin Burwell conveyed half of his land to his son Nathaniel,[4] who later sold it in 1771. After Robin Burwell’s death, controversy erupted over who owned various portions of the original grant.[5]

In 1798, after the legal problems had been sorted out, Robert Carter Burwell inherited his grandfather’s land of about 1,000 acres lying roughly between Long Branch Creek and Rattlesnake Spring.[6]

Around 1790, Robert Cater Burwell established Long Branch Plantation and began farming wheat.[7] During the early years of the plantation, Burwell lived with his sister and brother-in-law just north of Long Branch at Rattlesnake Plantation, currently known as Rosney. In the beginning of the 19th century Burwell began to plan his own home, just south of Rosney near Long Branch Creek.

In 1811, Burwell had planned a large, two-story brick home with an east wing. Burwell consulted with architect, Benjamin Henry Latrobe during construction.[8] After the start of construction of the plantation house, Burwell left in the summer of 1813 to fight in the War of 1812. He died later that year of diseases he contracted while stationed in Norfolk.[9] He willed his land to his sister, Sarah Nelson and her husband Philip.[10] It is unknown whether Burwell finished construction of the mansion before his death or if Sarah and Philip continued construction upon their inheritance.

In 1842, Philip Nelson sold Long Branch to his nephew, Hugh Mortimer Nelson and his wife Anna Maria Adelaide Holker.[11] This was the first time Long Branch changed hands in a financial transaction and the last until 1957. When Hugh M. Nelson and his wife Adelaide moved to Long Branch with their three-year-old daughter, Nannie, they started a large renovation and expansion of the property.[12] In 1847, Hugh Nelson Jr. was born.

After moving to Virginia from Baltimore, Maryland,[13] Hugh and Adelaide took to life as Virginia planters and assumed a leading role within Millwood's society. Hugh Nelson took command of the Clarke Cavalry,[14] served as a justice of the peace,[15] and was a vestryman for the Christ Church. Their position in Millwood's society came with considerable expense. As early as 1850, Nelson started to take out loans against Long Branch. He took out several debts and left many bills unpaid.[16] There is little evidence that Adelaide knew of any financial troubles.

In 1861, Hugh M. Nelson organized the Clarke Cavalry and reported for duty to fight with the Confederate Army.[17] After fighting in the Seven Days Battles, Nelson fell sick with typhoid and died on August 6, 1862. Long Branch escaped much damage during the war. Reports of the fields being burned was the extent of any damage done.

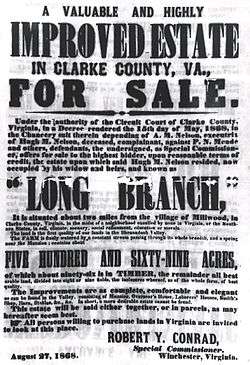

After the war, Adelaide discovered the debt and was in danger of losing Long Branch. The plantation had decreased in value. In 1860, Long Branch was assessed for $103,600. By 1870, it had decreased to the value of $45,000.[18] In 1867, after much legal battle, the courts had ordered the personal effects of Hugh Sr. be put to auction. Adelaide and her son, Hugh Nelson Jr. bought back the majority of the plantations possessions.[19] In 1869, the courts ordered that the house and farm where auctioned off to pay off the remaining debts. The land was auctioned off in two plats, half of the land in one and 280 acres with the house and old buildings. Adelaide was the only bidder for the lot with the house.[20] Eight months after Adelaide died of pneumonia in 1875, Hugh Nelson Jr. bought back the other half of the farm[21] and the entire farm was restored to the family by court decree in 1884.[22]

Hugh Nelson Jr. and his wife, Sallie Page Nelson, lived at Long Branch and established a reputation for their hospitality and entertaining. After the death of Hugh Nelson Jr. in 1915, Sallie Page Nelson remained at Long Branch until her death in 1951.

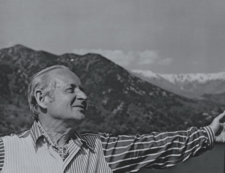

In August 1957, Long Branch was sold to Abram and Dorothy Hewitt.[23] At the time of the sale, Long Branch had deteriorated and the Hewitt’s worked to repair and renovate the house. They lived at Long Branch, raising their four sons until 1978 when they sold Long Branch to two doctors from California.[24] In 1982, they sold to a Texas businessman and horse breeder.[25] The condition of Long Branch had deteriorated significantly and the mortgage defaulted on. Once again, Long Branch was auctioned on the steps of the Clarke County Courthouse. In 1986, Harry Z. Isaacs, a Baltimore textile executive and horse breeder, purchased the house and land for $1.35 million.[26]

Isaacs began an extensive restoration of Long Branch. Shortly after the start of the restoration, Isaacs learned he had terminal cancer. Upon his death, he left the house and 400-acres to a non-profit foundation and opened Long Branch to the public.

Architecture

Built in 1811, Long Branch is a Federal style, two-story, Flemish bond, brick mansion. The symmetrical façade has seen little changes over the years. The south façade was the original front of the house; changing after Harry Isaacs constructed new roads throughout the property. The belvedere and front and back porticos were added in 1845 by Hugh M. and Adelaide Nelson. The south portico boasts Ionic columns and the north portico has Tuscan columns.

The east wing was a service wing with an open loggia that was enclosed in the Nelson renovation of 1845. They added the woodwork in the parlor and original dining room, which is based off the designs of Minard Lefever’s pattern books and has been called “some of the most beautiful examples of Greek Revival woodwork in the nation.”[27] Hugh M. Nelson also added the hanging spiral staircase and the columns in the entrance hall.

Indoor plumbing was added some time before 1915, with two identical bathrooms on the first and second floors were added to the northwest rooms. Electricity and a modern kitchen were added after WWII.[28] The Hewitt’s made improvements to the house and updated its amenities without altering the structure.

Harry Z. Isaacs made a number of changes to Long Branch. He added the west wing to balance the exterior of the house and completed a number of extensive reconstructions. Structural issues required the south wall of the east wing to be rebuilt. The east wing dining room was enlarged and the size of the kitchen reduced. A stairwell to the basement was removed to make a pantry. Isaac’s restoration involved the removal and replacement of existing materials and features. The brick sidewalks, shutters, columns, portico details and features, chimneys, roofing, gutters, exterior brick, and mantels were all replaced with modern reconstructions.

Benjamin Latrobe

Latrobe commented on Burwell’s plans and made a number of criticisms. He noted the location of the dining room and bedroom on the north side of the house. “In the summer you will be plagued in the evening after dinner by the western sun, and in the winter by the N. West wind.” The largest criticism was the lack of a servant staircase in Burwell’s plans. Without a second stair, servants would be unable to go upstairs without using the main staircase and crossing the central hall. The back staircase to the left of the central stair is believed to be a direct result of Latrobe’s comments. Overall Latrobe described the Long Branch plans as, “infinitely a better one than almost any other which I have seen adopted in Virginia, and the house would be a good one without any alteration.” While Latrobe made comments to the plans Burwell sent them, there is no evidence that Latrobe ever visited the site or directly drew plans for Long Branch.[29]

Grounds

Agriculture

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Shenandoah Valley was a productive and expanding agricultural region. The Valley farmers took advantage of the fertile land and created a booming commercial agricultural industry. Corn, hay, and various other grains dominated the region. Wheat served as the most prominent cash crop in the valley.[30] The owners of Long Branch capitalized on this market and maintained a wheat plantation into the mid-19th century.

The wheat from Long Branch was likely ground at the Burwell-Morgan Mill in Millwood and transported to the markets in Alexandria before being shipped to Europe.

Records show, that while wheat was the main crop at Long Branch, corn was a secondary crop for the plantation. Letters written by the residents of Long Branch explain their hope for the corn after the wheat crop failed.

Over the years, Long Branch has raised a variety of livestock including, cow, sheep, horses, pigs, and chickens.

Gardens

Through the 1800s much of Long Branch’s land was taken up by the wheat plantation. The main house was supported by a greenhouse (burned down in 1861),[31] orchards, and kitchen gardens. Records show that roses, chrysanthemums, and violets were grown on the property. The orchard had cherries, plums, and peaches. The kitchen gardens grew a variety of vegetables and herbs. By the 1930s the gardens were lost,[32] however, the Hewitts reintroduced the flower and kitchen gardens to Long Branch.

In 1997, the Sheila Macqueen Gardens were established at Long Branch. The flower gardens are dedicated to the notable British flower arranger, Sheila Macqueen. The gardens feature herbs, hellebores, hostas, Constance Spry Roses, and a variety of plant species native to Macqueen’s English Gardens. Today the gardens are sustained by the Sheila Macqueen Flower Ladies.

Outbuildings

Pictorial records and oral histories indicate that Long Branch had a grouping of outbuildings fairly close to the house. Various owners have built and demolished these outbuildings over the years. Up to the mid-20th century a number of buildings had survived. These include the summer kitchen, slave quarters, privy, smokehouse, icehouse, and two carriage barns. An 1868 auction handbill states that Long Branch had an overseers’ house, laborers’ houses, blacksmith shop, and barns and stables. A greenhouse was located on the property but burned in 1861. The summer kitchen collapsed in 1965 and an office was rebuilt in its place and was paneled with wood from an old sheep shed. A bank barn survived until 1971 when it burned down. Only the smokehouse and springhouse remain.

A pool was added by the Hewitts’ and later taken out by Isaacs.

Harry Isaacs constructed numerous outbuildings that stand today. The large horse barn, a machinery shed, two garages, and two houses near the north and south entrances of the property.

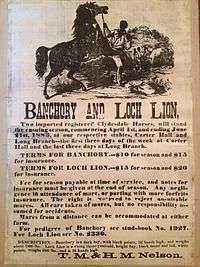

Horses

Horses have been an integral part of the history at Long Branch. Originally horses were used to help plow the fields and pull carriages. Hugh Nelson Jr. was an avid horse breeder, raising thoroughbreds and Clydesdales. Abram Hewitt and Harry Isaacs continued the horse breeding tradition at Long Branch, each having their own well-known operations.

Today, Long Branch has an extensive boarding program for the care of retired sport horses.

Slavery

As a large wheat plantation, Long Branch used enslaved workers to tend to the fields as well as the families house and gardens. At the peak of operation, the plantation utilized 20-30 slaves for the planting and harvesting of the crop. In addition to the main farming tasks, slaves also tended to the flower and kitchen gardens and helped with the maintenance and cleaning of the mansion.

The residents of Long Branch utilized slave labor until the end of the Civil War. At least one family was rehired after emancipation to continue as free labor on the farm.[33]

Museum

After his death in 1990, Harry Z. Issacs left Long Branch to a non-profit foundation. The Harry Z. Isaacs foundation has headquarters in Baltimore with a local board of directors. Tyson Gilpin, chaired the board of directors, oversaw the daily operation of the estate and Colette Poisson, as assistant to Isaacs, became the curator. On April 3, 1993, Long Branch was opened to the public.

In 2013, Long Branch underwent an extensive update to the museum. The museum installed new history exhibits and period rooms with an updated self-guided tour and new museum programming.

Long Branch Plantation hosts many special events and weddings on location.

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ↑ Robert Carter land division, Northern neck deed book C, p. 27

- ↑ Chappelear, B. Curtis, "Robert Burwell's land on the Shenandoah River," Proceedings of the Clarke County Historical Association, Vol. 5, 1945

- ↑ Decree, Henderson vs. Burwell et al., Nov. 20,1788, Virginia Historical Society

- ↑ Deed, Robert Carter Burweel's executor to Robert Carter Burwell, Dec. 3, 1798, deed book 25, p. 458, Frederick County Circuit Court

- ↑ Long Branch Plantation ledger book, 1796

- ↑ Carter, Edward C., Thomas Jeffrey, eds., The Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe (Clifton, N.J.: Published for the Maryland Historical Society by J.T. White, 1976)

- ↑ Proceedings of the Clarke County Historical Association(PCCHA), Vol. 14, 1956-57, p. 61

- ↑ Will book 9, p. 263, Frederick County Circuit Court

- ↑ Deed, Philip Nelson and wife to Hugh M. Nelson, March 23, 1842,deed book B, p. 221, Clarke County Circuit Court

- ↑ Clarke County land tax records, Virginia State Library

- ↑ Johnson, Rev. John Lipscomb, The University Memorial Biographical Sketches of Alumni of the University of Virginia Who Fell in the Confederate War p. 206-216

- ↑ Musick, Michael P., Sixth Virginia Cavalry (H.E. Howard inc.: Lynchburg, Va., 1990), p. 3

- ↑ Order signed by Hugh Nelson in his capacity as justice of the peace, Burwell Family papers, Virginia Historical Society

- ↑ Creditors' accounts, Nelson vs. Arnett, Clarke County Circuit Court

- ↑ Musick, Sixth Virginia Cavalry, p. 141

- ↑ Censuses of 1861 and 1870, Hadley Library

- ↑ Sale account of Hugh M. Nelson's personal property, will book F, p. 1, Clarke County Circuit Court

- ↑ Nelson's Adm'r v. Kownslar's Ex'or & others, University of Virginia

- ↑ Nelson Adm'r vs. Kownslar's Exec'r, p. 4

- ↑ Hansbrough, Reports of Cases Decided in the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia, p. 479

- ↑ Deed, Nannie N. Huidekoper to Abram Hewitt, deed book 52, p. 388, Clarke County Circuit Court

- ↑ Deed, April 28, 1978, deed book 127, 9. 372, Clarke County Circuit Court

- ↑ Deed, March 31, 1982, deed book 146, p. 40, Clarke County Circuit Court

- ↑ The Winchester Star, Sept. 17, 1986, p. 13

- ↑ Loth, Calder. Letter to Harry Z. Isaacs. 22 Oct. 1986.

- ↑ Fordney, Christopher Long BranchA Plantation House in Clarke County, Virginia(Harry Z. Isaacs Foundation, Millwood, Va., 1995)

- ↑ Edward C. Carter, Thomas E. Jeffery, eds. The Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe(Clifton, N.J.: Published for the Maryland Historical Society by J.T. White, 1976)

- ↑ Schlebecker, John T., "Farmers in the Lower Shenandoah Valley, 1850," The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 79, No. 4, October 1971, pp. 463-476

- ↑ Letter, W.L. Bent to Adelaide Nelson, Sept. 21,1861

- ↑ Christian and Massie, Homes and Gardens in Old Virginia, p. 167

- ↑ Census of 1870, Handley Library

Further reading

- Fordney, Christopher R. Long Branch: A Plantation House in Clarke County, Virginia. Millwood, VA: H.Z. Isaacs Foundation, 1995. Print.

- Hamlin Talbot, Benjamin Henry Latrobe (New York: Oxford University Press, 1955) ISBN 0-1950-0563-5

- Masson, Kathryn and Brooke, Steven (photographer); Historic House of Virginia: Great Plantation Houses, Mansions, and Country Places; Rizzoli International Publications; New York City, New York; 2006 ISBN 0-8478-2861-1

- Phillips, Edward H., The Lower Shenandoah Valley in the Civil War: The Impact of War Upon the Civilian Population and Civil Institutions (Lynchburg, Va.: H.E. Howard Inc., 1993) ISBN 1-5619-0042-7

- Vlach, John Michael, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill, N.C,: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993) ISBN 0-8078-4412-8