PNS Ghazi

- For the submarine named Ghazi, bought by the Pakistan Navy in 2000, see NRP Cachalote (S165)

Ghazi in action. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USS Diablo (SS-479) |

| Builder: | Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Kittery, Maine, United States[1] |

| Laid down: | 11 August 1944[1] |

| Launched: | 1 December 1944[1] |

| Commissioned: | 31 March 1945[1] |

| Decommissioned: | 1 June 1964[1] |

| Struck: | 4 December 1971[2] |

| Fate: | Transferred to Pakistan on 1 June 1964[1] |

| Name: | PNS Ghazi |

| Cost: | $1.5 million USD (1968) (Refit and MLU cost)[3] |

| Acquired: | 1 June 1964 |

| Refit: | 2 April 1970 |

| Honors and awards: |

|

| Fate: | Sank during the Indo-Pakistan War, 4 December 1971[4][5][6][7] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Tench-class diesel-electric submarine[2] |

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 311 ft 8 in (95.00 m)[2] |

| Beam: | 27 ft 4 in (8.33 m)[2] |

| Draft: | 17 ft (5.2 m) maximum[2] |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | |

| Range: | 11,000 nautical miles (20,000 km; 13,000 mi) surfaced at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph)[11] |

| Endurance: |

|

| Test depth: | 400 ft (120 m)[11] |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

PNS Ghazi (previously USS Diablo (SS-479); reporting name: Ghazi), SJ, was a Tench-class diesel-electric and the first fast-attack submarine of Pakistan Navy (PN), leased from the United States in 1963.:68[12]

She briefly served in the United States Navy from 1945–63 and was loaned to Pakistan under the Security Assistance Program (SAP) on a four-year lease after Ayub administration successfully negotiating with the Kennedy administration for the procurement.[13] In 1964, she joined the Pakistan Navy and saw the military actions in the Indo-Pakistani theaters in 1965 and, later in 1971.[3]

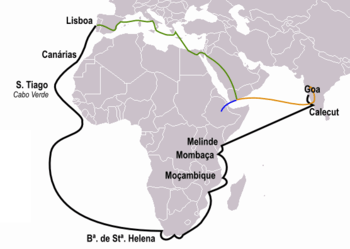

In 1968, she executed a circumnavigation of Africa and southern parts of Europe through the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic ocean due to the closure of the Suez Canal in order to be refit and update its computers from Gölcük in Turkey, and could be armed with up to ~28 Mk.14 torpedoes as well as had capability of mine-laying as part of her upgradation.[3][14]

Starting from being the only submarine in the war theater in 1965, it remained the Pakistan Navy's flagship submarine until she sank near India's eastern coast while conducting the naval operations en route to the Bay of Bengal under mysterious circumstances.[15] While the Indian Navy credits Ghazi's sinking to its destroyer INS Rajput,[4][5][6][16][17] however, the Pakistani military oversights stated that "the submarine sank due to either an internal explosion or accidental detonation of mines being laid by the submarine off the Vishakapatnam harbour" with neutral sources confirming that the Rajput still in its port when the submarine sank.[7][18][19][20][21]

The Indian historians considers the sinking of Ghazi as a notable event and termed its sinking as one of the "last unsolved greatest mysteries of the 1971 war."[21]

Service with United States Navy

The Diablo, a long-range fast-attack Tench-class submarine was launched on 1 December 1944, sponsored by the wife of U.S. Navy's Captain V. D. Chapline on 31 March 1945 with Lieutenant Commander Gordon Graham Matheson as her first commanding officer.[22][23][24][25]

She was the only warship of the U.S. Navy to be named Diablo, which means "Devil" in the Spanish.:134–135[26] Its assigned and issued insignia patch identified the caricature image of Devil running with a torpedo in the sea.[27]

As her keel was laid down by the Portsmouth Navy Yard, Diablo arrived at Pearl Harbor from New London in Connecticut, on 21 July 1945 and sailed for her first war patrol 10 August with instructions to stop at Saipan for final orders.[25] With the ceasefire, her destination was changed to Guam where she arrived on 22 August 1945.[1] On the last day of the month, she got underway for Pearl Harbor and the East Coast arriving at New York City on 11 October, except for a visit to Charleston in South Carolina in October where she remained at New York until 8 January 1946.[24]

From 15 January 1946 to 27 April 1949, Diablo was based in the Panama Canal Zone participating in fleet exercises and rendering services to surface units in the Caribbean Sea.[2] From 23 August to 2 October 1947, she joined the Cutlass (SS-478) and Conger (SS-477) for a simulated war patrol down the west coast of South America and around Tierra del Fuego.[11] The three submarines called at Valparaíso, Chile, in September while homeward bound. Diablo sailed to Key West in Florida, for antisubmarine warfare exercises, from 16 November to 9 December 1947, and operated from New Orleans in Louisiana, for the training of naval reservists in March 1948.[11]

Diablo arrived at Naval Station Norfolk in Virginia, her new home port, on 5 June 1949, and participated in Operation Convex in 1951, and alternated training cruises with duty at the Sonar School at Key West.[1] Her homeport became New London in 1952 and she arrived there 17 September to provide training facilities for the Submarine School.[22]

From 3 May to 1 June 1954, she was attached to the Operational Development Force at Key West for tests of new weapons and equipment.[22] She participated in Operation Springboard in the Caribbean from 21 February to 28 March 1955, and continued to alternate service with the Submarine School with antisubmarine warfare and fleet exercises in the Caribbean and off Bermuda, as well as rendering services to the Fleet Sonar School and Operational Development Force at Key West.[24] Between February and April 1959, she cruised through the Panama Canal along the coasts of Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Chile for exercises with South American navies.[22] On 27 May 1960, she entered Philadelphia Naval Shipyard for an overhaul which continued through October 1960.[25]

In 1962, her hull classification symbol was changed to AGSS-479.[2]

Service with Pakistan Navy

_in_Cape_Cod_Canal.jpg)

The procurement and acquisition of Ghazi was a result of lengthy and complicated negotiation between the administrations of Pakistan and the United States.:57–60[28] Since 1950s, Pakistan Navy had been pushing for an idea of procuring imported submarines, first starting the negotiation with the Royal Navy and extended its talks to the United States Navy.:58[28]

With Ayub administration sweetening relations with the Eisenhower administration in 1960, Ghazi was finally procured under the Security Assistance Program (SAP) authorised by the Kennedy administration on a four-year lease with an option of renewing or purchasing the submarine afterwards in 1963.[3][14]

Ghazi was the first submarine to be operated by a Navy in the South Asia becoming a serious threat to the Indian Navy.[28][29]:60 On contrary to popular perception, Ghazi technological feats were downgraded and extensively refitted its Fleet Snorkel under the Guppy program of the U.S. Navy at the Philadelphia Naval Dockyard, and was mostly unmodernized when she joined the services of Pakistan Navy.:61[28] Naval historians had described the Ghazi as an unarmed "clockwork mouse" used for training purposes.:61[26][28]:135–136 Nonetheless, the Indian Navy immediately was under the impression that it was militarized and an updated submarine that poses serious threats.:59[28]

She was fitted with 14 vintage Mark-14 torpedoes which had the controversy and notoriety of its own during the World War II.[3] On 4 September 1964, she arrived and reported to Naval Dockyard in Karachi and joined the Navy as its first-ever long-range fast-attack submarine.[30] She was named and designated as "Ghazi" (lit. Holiest Warrior) by the Pakistan Navy in 1964.:136[26]

Indo-Pakistani war of 1965

On August 5 of 1965, the war broke out between India and Pakistan as a result of covert infiltration in Indian-held Kashmir, and Ghazi, at that time, was under the command of then-Commander Karamat Rahman Niazi, who would later ascend as a four-star admiral in the Navy.[30] Other officers who served in the Ghazi were then-Lieutenant-Commander Ahmed Tasnim (later promoted as Vice-Admiral) and Lieutenant Zafar Muhammad who would later command her, as a Commander, in 1971.[31]

She was the only submarine in the conflict arena that was deployed in the war theatre with a mission scope of attacking only heavy and major warships of the Indian Navy.[32] She only aided the flotilla under the command of Commodore S.M. Anwar that launched a naval attack on radar station in Dwarka, Gujarat, India.[30] In addition, she was also stalking the INS Vikrant, the only aircraft carrier, but did not detect her target during the entire conflict.[3] On 9 September 1965, the INS Beas made an unsuccessfully depth charge attack in an attempt to make a contact with Ghazi.[3]

On 17 September 1965, Ghazi made a surface contact and identified INS Brahmaputra and fired three World War II-origin Mark 14 torpedoes and increased its depth to evade the counterattack.[3] According to submarine war logs, there were three distinct explosions that were heard at the time when the torpedoes had impacted but Brahmaputra was not sunk neither it had been hit it since the warship did not released the depth charge nor it had detected the homing signal.[3] No ships were sunk or damaged in the area and Ghazi safely reported back to its base.[3]

Upon her return, she won 10 war awards including two decorations of Sitara-e-Jurat, one Tamgha-i-Jurat, and the President's citations and six Imtiazi Sanads while her commander, Cdr. K.R. Niazi was decorated with the Sitara-e-Jurat and chief petty officers were decorated with the Tamgha-i-Jurat.[30][31] It is not known what Ghazi's target was or what were the three mysterious explosions were since no inquiry report was ever submitted.[3]

After the war, the arms embargo was placed in 1965–66 on both India and Pakistan but was later waived by the United States that was strictly based on the cash and carry method as Ghazi badly needing a refitting.[3] In 1967, the Navy applied to renew another four-year lease deal which was duly approved by the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Government but her material state and equipments continued to deteriorate.:108[13] The Navy then signed a deal with the Turkish Navy for a refit and mid-life update that was to be carry out at Gölcük in Turkey– the only facility to update the Tench-class submarines.[3]

Because of the Six-Day War in Middle East which had close the Suez Canal due to the Egyptian Navy's blockage in 1967, Ghazi, under the command of Commander Ahmed Tasnim, had to execute the submerged circumnavigation in 1968 from Africa to Western Europe which began from Karachi coast to Cape of Good Hope, South Africa through Atlantic Ocean and ended at the east coast of the Sea of Marmara where the Gölcük Naval Shipyard is located.:108[3][13][14] Chief of Naval Staff Admiral S.M. Ahsan had arranged necessary refitting of Ghazi's computers at the Karachi Engineering and Shipyard Works (KESW) from the help from the local industry such as DESTO.[14]

During her submerged circumnavigation voyage, she briefly stopped at Mombasa in Kenya for refueling and, in Maputo located in Mozambique before making a farewell visit at the Simon's Town in South Africa.[14] From passing through the Cape of Good Hope, she made another stopover at the Luanda, Angola for food ration and continued her journey towards Western Europe to stopover at the Toulon in France where she was greeted by the French Navy.[14] Her final stopover was at the İzmir in Turkey and submerged through the east coast of the Sea of Marmara to docked at the Gölcük Naval Shipyard where it was the only facility to upgrade the Tench-class based computers and other electromechanical equipments.[14] It took her two months to complete her circumnavigation of Africa and Europe.[14]

The deal of refitting and mid-life upgradation of her military computers was reported cost at ~$1.5 million ($11.1 million in 2015–16).[3] The program started in March 1968 and completed in April 1970 and it is believed that the U.S-made ill-fitted World War II era Mk.14/Mk.10 naval mines were bought "under the table" from Turkey.[3]

Indo-Pakistani war of 1971

Under the command of Lieutenant Commander Yousaf Raza, Ghazi returned to Karachi coast after successfully completing the submerged circumnavigation of Africa which was taken in order to undergo a refitting program and mid-life updates of her military computers on 2 April 1970.:108[13][14]

On August 1971, the Indian Navy transferred the INS Vikrant, the aircraft carrier, to its Eastern Naval Command at the Vishakapatnam that forced the Pakistan Navy to adjust its submarine operations.[3] Before 1971, there were several proposals made to Ayub administration to strengthened the naval defense of East Pakistan but none were made feasible and the Navy was in no position to mount a defence against approaching Indian naval advances.[30] After the defection of officers and sailors of East-Pakistan Navy to India, the Eastern Command had been intense pressure to counter the insurgency and Indian Army's advancement towards the East Pakistan on three fronts.[30] The Yahya administration insisted the Navy to reinforce the naval defence of East and Navy NHQ had objected the idea of deploying Ghazi in total absence of seaport that stray away from their original plans.[30] Many senior commanders had felt that the deployment of Ghazi was highly dangerous and impossible to achieve by sending an obsolete submarine behind enemy lines but deployment came with it became apparent that the war was inevitable.[30]

Prior to her deployment, Ghazi continued to experience equipment failures and reportedly had aging issues despite it was the only submarine had the range capability to undertake operations in the distant waters under control of the enemy, was pressed into operation to destroy or damage Vikrant.[33] Her commanding officer, Commander Zafar Muhammad, was first time commanding a submarine had undertook the dangerous task.[3] On 14 November 1971, she quietly sailed off to 3,000 miles (4,828km) around the Indian peninsula from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal under the command of Zafar Muhammad who was commanding a submarine the first time, with 10 officers and 82 sailors.[30] Ghazi had two-fold mission: the primary goal was to locate and sink Vikrant with secondary objective to be accomplished with or without the primary, was to mine India's eastern seaboard.[3]

Fate

The mysterious sinking of Ghazi took place somewhere around 4 December 1971 during its hunt to assault the Vikrant and/or mine-laying mission on Visakhapatnam Port, Bay of Bengal.[33]

On 16 November, she was in contact with the Navy NHQ and Commander Khan chartered the coordinates that reported that she was 400km off Bombay.:82[34] On 19 November, she was off to Sri Lanka and entered in Bay of Bengal on 20 November 1971.:82[34] Around this time, the Top Secret files were open as instructed and the hunt for Vikrant began on 23 November off to Madras but she was 10 days late and the Vikrant was actually somewhere near the Andaman islands.:82[34][35] Unable to detect her target, Ghazi's commanders became delusional from their hunt for Vikrant and turned back to Visakhapatnam to started laying mines off the harbour in a confidence that it will take its swipe at the "Vikrant or at least bottle up the Indian Navy's heavy units clustered in this major Indian naval base in the night of 2–3 December 1971."[30]

On 1 December 1971, Vice Admiral Nilakanta Krishnan briefed Captain Inder Singh, commanding officer of INS Rajput, that a Pakistani submarine had been sighted off Sri Lanka and was absolutely certain that the submarine would be somewhere around either Madras or Vishakapatnam.[36] He made it clear that once Rajput had completed refueling, she must leave the harbor with all navigational aids switched off.[36]

According to Indian claims, at 23:40 on 3 December 1971, taking on board a pilot, Rajput moved through the channel to the exit from Vishakhapatnam.[36][37]

Exactly at midnight, shortly after passing the entrance buoy, starboard lookout reported breaker on the surface of the water right on the nose. According to the Indian Navy's claims, Captain Singh, changing the course at full speed across the specified point and ordered to loose two depth charges, which was done.[36] The explosions were "stunning", and the Rajput suffered a serious material concussion to its structure. However, visible results of this attack are not given.[36] Rajput for some time surveyed the area dumping bombs, no longer found any contact — either visual or acoustic. A few minutes later, the destroyer continued on her way to the coast of East Pakistan.[36][37]

On 4 December 1971, Ghazi sank with all 92 men on board due to the unknown and mysterious:157[33][38] circumstances off to the Vishakapatnam coast, allowing the Indian Navy to effect a naval blockade of then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).:157[38]

Intelligence and deception

According to Indian DNI's director Rear-Admiral Mihir K. Roy, its existence was revealed when a signal addressed to naval authorities in Chittagong was intercepted, requesting information on a lubrication oil only used by submarines and minesweepers.[33][39]

Indian Navy intelligence tracked Ghazi with a codename issued as Kali Devi,[40] and Indian Navy began to realize that the Pakistanis would inevitably be forced to send their submarine Ghazi to the Bay of Bengal, as the sole ship which could operate in these waters.[40]

Vice Admiral Nilakanta Krishnan of Eastern Naval Command had maintained that it was pretty clear that Pakistan would have deployed the Ghazi in the Bay of Bengal and a part of its plan was an attempt to sink the Indian aircraft carrier Vikrant.[3] At the same time concerted action was taken to disseminate misinformation designed to mislead the enemy about the true location of the aircraft carrier, and to foster confidence that the carrier was stationed at Visakhapatnam.[3][36]

All these activities were apparently successful in deceiving the Ghazi when on 25 November 1971, the Navy NHQ communicated with Ghazi that stated: "INTEL INDICATES CARRIER IN PORT VISHAKAPATNAM".[37]

Aftermath

On 26 November 1971, Ghazi was expected to communicate with the Navy NHQ to submit its mission report but did not communicate with its base.[41] The Navy NHQ repeatedly made frantic efforts to establish the communication and anxiety grew day pass for her return to the base.[41] Before the naval hostilities broke out, officers commanding had worried about the Ghazi's fate and had already began to agitate their minds but the Navy NHQ senior command had replied to their junior officers that several reasons could, however, be attributed to the failure of the submarine to communicate.[41]

On December 9, Indian Navy strangely issued a statement about the fate of Ghazi when the first indication of Ghazi's tragic fate came when a message from the Indian NHQ, claiming sinking of Ghazi on the night of 3 December, was intercepted.[41] The Indian NHQ issued the statement a few hours before the loss of INS Khukri, and prior to launch of second missile attack on Karachi port.[41]

Indian version

After the ceasefire in 1971, Government of India undertook an investigation into the incident and immediately claimed that the submarine was sunk following the series of maneuvers by the Indian Navy.[41] A submarine rescue vessel, INS Nishtar was sent to check the debris and India later built a "Victory Memorial" on the coast near where the Ghazi was sunk.[42] India credits the INS Rajput for sinking the Ghazi and her crew were honored with the gallantry awards for this event, but the actual details of Ghazi's sinking soon began to emerge after the war.[2]

The claim of sinking Ghazi has been a center of controversy between the responsible Indian authors, giving doubts in their theories of mysterious sinking of the submarine.[41] With Commodore Ranjit Roy testifying that "very loud explosions effects were heard at the beach that came from underwater."[41] Commodore Roy also concluded that "...at that time, how the Ghazi was sunk remained unclear as it does today."[41]

The official history of Indian Navy: ‘Transition to Triumph’, authored by retired Vice-Admiral G.M. Hiranandani, gave exhaustive account of the sinking of the Ghazi and quoted that the naval records and top naval officials who commanded operations on the eastern seafront as saying that INS Rajput was sent from Visakhapatnam to track down Ghazi. The book also noted that the time of dropping of the charges, the explosion which was heard by the people of Visakhapatnam and that of a clock recovered from Ghazi, matched.[43] However, Admiral Hiranandani maintained that the submarine almost certainly suffered an internal explosion but its causes are debatable.[21]

Admiral Roy of India states: "The theories propounded earlier by some who were unaware of the ruse de guerre (attempt to fool the enemy in wartime) leading to the sinking of the first submarine in the Indian Ocean gave rise to smirks from within our own (Indian) naval service for an operation which instead merited a Bravo Zulu (flag hoist for Well Done)".[39]

Admiral S. M. Nanda, Chief of Naval Staff of Indian Navy during the conflict, stated : "In narrow channels, ships, during an emergency or war, always throw depth charges around them to deter submarines. One of them probably hit the Ghazi. The blow-up was there, but nobody knew what it was all about until the fisherman found the lifejacket".[44]

In 2003, Indian Navy again sent its divers to overlooks its investigations and the divers recovered some items including the war logs, officials backup tapes from her computers, and mission files that were displaced in Eastern Naval Command of Indian Navy, but the divers who studied the wreckage confirmed that the submarine must have suffered an internal explosion which blew up its mines and torpedoes.[45] Another theory that they suggests an explosion of hydrogen gases violently built up inside the submarine while its batteries were being charged underwater.[21]

In 2010, Lieutenant-General J.F.R Jacob of Eastern Command opined an article and maintained that: "Ghazi had met an accidental end and the Indian Navy had nothing to do with its sinking, hence the destruction of the records.[46] There were many opinions from authors of the Indian side who also share this scepticism of the Indian Navy’s official stance.[46]

In 2011, former Indian naval chief, Admiral Arun Prakash qouted in the national security conference that [Ghazi] had sunk in mysterious circumstances, "not by INS Rajput as originally claimed."[47]

Pakistani military oversights

In 1972, the Hamoodur Rahman Commission (HRC) never carried out the investigations into the incident despite it was formed to assessed the military and political failures of the country in the war in 1971.[48]

It was only on February 10 of 1972, when the incident was officially recognized by Government of Pakistan and then-President Zulfikar Bhutto met with the families and loved ones of the officers and sailors who served in Ghazi, and told them that they may have all perished due to this incident as many of the slain family members were pushing for repatriation to the Government of Pakistan as they were keeping the hope alive that they may have survived and rescued by India.[41]

The Naval Intelligence conducted its own investigations and its military oversights stated that the Ghazi sank, when the mines it was laying, were accidentally detonated.[49] Pakistani military oversights into this incidents were not immediate instead, the Naval Intelligence took time to conclude its investigations that went on over the several years.[3] Over the decades, the military oversights were kept hidden and was not known to the public until 1990s when the Navy made an announcement over the completion of its insights into this incident.[3][30] Following this announcement, Pakistan addresses the problems connecting the electromechanical failures, computer problems, and Mk.14 torpedoes' "circular deep running" once launched from the firing ship.[3]

Pakistan never accepted the theory from Indian Navy but provided its alternative insights into this disaster based on the investigations on the Mark 14 torpedoes and other vintage military equipment installed in the Ghazi.[3] According to Pakistan Navy's investigation, there were two probable reasons connecting to this mishappening:

- *Magnetic Exploder/Hydrogen explosion: A Sargo-type lead-acid battery may have over-produced the Hydrogen gas during their charging of submarine's batteries that may have led the violent internal explosion.[40]

- *Detonation of a mine inside the submarine: This was often cited by the Pakistan Navy as the World War II-era Mk.10/Mk.14 torpedoes may have deep "circular" run, failing to straighten its run once set on its prescribed gyro-angle setting, and instead, to run in a large circle, thus returning to strike the firing ship.[30][49][50][51]

Another more plausible theory from foreign experts, also favored by Pakistan, is that the explosive shock waves from one of the depth charges set off the torpedoes and mines (some of which may have been armed for laying) stored aboard the submarine.[36][41] The Navy NHQ counter-argued: the Ghazi itself may have inadvertently passed over the mines during the mine laying operations; patrolling Indian vessels or Indian depth charges may also have tripped the count mechanism of one or more mines.[41] Credibility is added to this story by the later discovery by Indian Coast Guard divers in 2003, that the damaged parts of the submarine had been blown inside out.[36][52]

In addition, the NI's investigations also exposed the ill-considered deployment of Ghazi when it was indicated that there was no indication that Ghazi's crew had ever practiced with mines.[3]

In 2006, Pakistan, citing their evidences, vehemently rejected India's claim of sinking Ghazi and termed the claims as "false and utterly absurd".[53]

Neutral witnesses and assessments

An independent testimony stems from an Egyptian Navy officer, who claimed that the Indian ships were docked at the Visakhapatnam harbour when the explosions from the supposed Indian sinking of Ghazi occurred, and that "it was not until about an hour after the explosion, that two Indian naval ships were observed leaving harbour".[18]

Many independent writers and investigators maintained the Ghazi was sunk mysteriously not by two depth charges alone– Ghazi many have sunk could sunk either by the hydrogen explosion produced when the batteries were chargings, or could be the detonation of a mine, or either by the sea floor impact while trying to avoid the depth charge released by the INS Rajput.[3][21][40]

In 2012, Pakistani investigative journalists from The Express Tribune who were affiliated with the Express News USA based in the Washington D.C. were able to get in touch with Diablo's' retired and now-aged former US Navy crewmembers who were allowed to study the sonar pictures and sketches of the sunken vessel where they believed that: "an explosion in the Forward Torpedo Room (FTR) destroyed the Ghazi."[46] This view is also shared by Indian journalist Sandeep Unnithan, who specialises in military and strategic analysis.[46]

Recovery of sunken vessel

In 1972, both the United States and the Soviet Union offered to raise the submarine to the surface at their own expense.[39] The Government of India, however, rejected these offers and allowed the submarine to sink further into the mud off the fairway buoy of Visakhapatnam.[39]

In 2003, Indian Navy divers recovered few items from the submarine and brought up six bloated bodies of Pakistani servicemen when they blasted their way into the submarine.[21] All six servicemen were given military honorary burial by the Indian Navy. Items recovered were the back-up tapes of the radar computers, war logs, broken windshield, top secret files, as well as recovering the one of the bodies of a Petty Officer Mechanical Engineer (POME) who had a wheel spanner tightly grasped in his fist.[21] Another sailor had in his pocket a poignant letter written in Urdu by his fiancé.[21]

In 2003, there were additional photos were released by the Indian Navy of the vessel.[21]

Legacy

In memory

In 1972, Ghazi and her serving officers as well as crew members were honored with the gallantry awards by the Government of Pakistan.[54][55] After the war, President Richard Nixon forgave the remaining debt of Ghazi to Pakistan when the U.S. Navy's CNO Admiral Elmo Zumwalt visited Admiral Mohammad Shariff in Chittagong in 1972.:219–226[39] In addition, she remained the first and yet to-date only U.S.-built submarine to be served in Pakistan Navy, although in successive years, only surface warships had been acquired through transfers from the United States as Pakistan worked towards building its own long-range submarines, the Agosta 90B, through a technology transfer from France.[56]

At the Naval Dockyard in Karachi, a "Ghazi Monument" was built to perpetuate the memory of the submarine and its 93 men.[57] In 1974, the naval base, PNS Zafar, was commissioned and constructed in the memory of Commander Zafar Muhammad Khan that now serves as headquarter for Northern Naval Command.[57] In 1975, the Navy acquired the Albacora-class submarine from the Portuguese Navy and was named "Ghazi (S-134)", in memory of PNS Ghazi.[58]

In 1998, the Inter-Services Public Relations produced and released the telefilm, Ghazi Shaheed that stars Shabbir Jan as commander of Ghazi, and Mishi Khan as Commander's wife; the telefilm is based on the events involving the Ghazi's mission and overlooks the lives of men who served in Ghazi.[59] Another movie, Untold Stories: Ghazi and Hangor was sponsored and released by the ISPR to commemorate the Ghazi and her martyrs during their missions in 1971.[55]

In 2016, the PNS Hameed was commissioned where Ghazi was honored and is namesake of her first officer, Lt.Cdr Pervez Hameed.[60]

Notable commanders

- Commander Karamat Rahman Niazi– later appointed as the four-star rank admiral, commanded from 1964–66.

- Commander Ahmed Tasnim– Hangor's commander in 1971 and later Vice-Admiral, commanded Ghazi from 1966-1969.

- Lieutenant Commander Yousaf Raza– commanded Ghazi from 1969-1971

- Commander Zafar Muhammad– the last commander until her sinking in 1971.

Honors and Awards

| Sitara-e-Jurat (Awarded in 1965 and 1971) |

President's Citation (Citation in 1965) |

Tamgha-i-Jurat (Awarded in 1965) |

See also

- Pakista Navy Submarine Command

- PNS Hangor

- Ghazi Shaheed–a 1998 Pakistani telefilm based on PNS Ghazi

- Ghazi– a 2017 Indian film based on PNS Ghazi

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Friedman, Norman (1995). U.S. Submarines Through 1945: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. pp. 285–304. ISBN 1-55750-263-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 280–282. ISBN 0-313-26202-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 wwiiafterwwii (24 December 2015). "Last voyage of PNS Ghazi 1971". wwiiafterwwii. wwiiafterwwii. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- 1 2 http://www.orbat.com/site/cimh/navy/kills%281971%29-2.pdf

- 1 2 "Rediff On The NeT: End of an era: INS Vikrant's final farewell". Rediff.com. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- 1 2 "The Sunday Tribune - Spectrum - Lead Article". Tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- 1 2 Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-first Century By Geoffrey Till

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bauer, K. Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. pp. 275–282. ISBN 978-0-313-26202-9.

- ↑ U.S. Submarines Through 1945 pp. 261–263

- ↑ U.S. Submarines Through 1945 pp. 305–311

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 U.S. Submarines Through 1945 pp. 305-311

- ↑ Karim, Afsir. "The Early Years". Indo-Pak Relations: Viewpoints, 1989-1996 (google books). Lancer Publishers. ISBN 9781897829233. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Hiranandani, G. M. "Pakistan Navy's Submarine Program". Transition to Triumph: History of the Indian Navy, 1965-1975 (google books). Lancer Publishers. ISBN 9781897829721. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Tasnim, Vice-Admiral Ahmed (May 2001). "Remembering Our Warriors - Vice Admiral Tasneem". www.defencejournal.com (in Eng). Vice Admiral A. Tasnim, Defence Journal. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Till, Geoffrey (2004). Seapower: a guide for the twenty-first century. Great Britain: Frank Cast Publishers. p. 179. ISBN 0-7146-8436-8. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ↑ http://www.deccanchronicle.com/151124/nation-current-affairs/article/visakhapatnam-sunk-pakistani-submarine-ghazi-enigma

- ↑ http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Visakhapatnam/from-a-small-outpost-to-a-major-command/article8150476.ece

- 1 2 Johnson, Ken. "PNS Ghazi" (PDF). Hooter Hilites (December 2007): 6. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- ↑ Joseph, Josy (12 May 2010). "Now, no record of Navy sinking Pakistani submarine in 1971". TOI website. Times Of India. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

Pakistani authorities say the submarine sank because of either an internal explosion or accidental blast of mines that the submarine itself was laying around Vizag harbour.

- ↑ "The truth behind the Navy's 'sinking' of Ghazi". Sify News website. Sify News. 25 May 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2010.

After the war, however, teams of divers confirmed that it was an internal explosion that sank the Ghazi.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Unnithan, Sandeep (26 January 2004). "New pictures of 1971 war Pak submarine Ghazi renew debate on cause behind blast on vessel". India Today, 2003. India Today. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 et.al. "USS DIABLO (SS-479) Deployments & History". www.hullnumber.com. Hull Number. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ "Diablo (SS-479) of the US Navy - American Submarine of the Tench class - Allied Warships of WWII - uboat.net". uboat.net. uboat.net. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 "TogetherWeServed - Connecting US Navy Sailors". navy.togetherweserved.com. TogetherWeServed -. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 "USS Diablo SS-497". www.historycentral.com. USS Diablo SS-497. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Sagar, Krishna Chandra. "The Devil can't be the Defender of the Faith". The War of the Twins (google books). Northern Book Centre. ISBN 9788172110826. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ Smolinski, Mike. "Patches of USS Diablo at the Submarine Photo Index". www.navsource.org. Submarine Photo Index. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Goldrick, James. No Easy Answers: The Development of the Navies of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, 1945-1996. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 9781897829028. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ Dittmer, Lowell. South Asia's Nuclear Security Dilemma: India, Pakistan, and China: India, Pakistan, and China. Routledge. ISBN 9781317459552. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Usman, Tariq. "The Ghazi That Defied The Indian Navy «". pakdef.org. PakDef Military Consortium. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- 1 2 Cardozo, Major General Ian. The Sinking of INS Khukri: Survivor's Stories. Roli Books Private Limited. ISBN 9789351940999. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- ↑ Roy, Mihir K. (1995). War in the Indian Ocean. Lancer Publishers. pp. 83–85. ISBN 978-1-897829-11-0. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Till, Geoffrey (2004). Seapower: a guide for the twenty-first century. Great Britain: Frank Cass Publishers. p. 179. ISBN 0-7146-8436-8. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- 1 2 3 Zakaria, Rafia. The Upstairs Wife: An Intimate History of Pakistan. Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807080467. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ In Quest of Freedom: The War of 1971 - Personal Accounts by Soldiers from India and Bangladesh. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9789386141668. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Bharat Rakshak Monitor: Volume 4(2) September–October 2001". Bharat-rakshak.com. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- 1 2 3 "Войны, история, факты. Альманах". Almanacwhf.ru. Retrieved 2011-12-16.

- 1 2 Till, Geoffrey. Seapower: A Guide for the Twenty-first Century. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780714655420. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mihir K. Roy (1995) War in the Indian Ocean, Spantech & Lancer. ISBN 978-1-897829-11-0

- 1 2 3 4 Khan, Commander Azam. "Maritime Awareness and Pakistan Navy". www.defencejournal.com. Defence Journal, Azam. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Shabbir, Usman. "Operations in the Bay of Bengal: The Loss of PNS/M Ghazi« PakDef Military Consortium". pakdef.org. Usman Shabbir, loss of Ghazi. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ "Victory at Sea memorial at Vizag".

- ↑ Vice-Admiral (Retd) G M Hiranandani, Transition to Triumph: Indian Navy 1965–1975. ISBN 1-897829-72-8

- ↑ Sengupta, Ramananda (22 January 2007). "The Rediff Interview/Admiral S M Nanda (retd) 'Does the US want war with India?'". Interview. India: Rediff. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ Trilochan Singh Trewn (July 21, 2002). "Naval museums give glimpse of maritime history". The Tribune. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Mulki, Muhammad Abid (27 May 2012). "Warriors of the waves". The Express Tribune. The Express Tribune, 2012 Mulki. The Express Tribune. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ "Ghazi sank due to internal explosion: Ex-Navy Chief". News X. News X. 14 September 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ http://www.pppusa.org/Acrobat/Hamoodur%20Rahman%20Commission%20Report.pdf

- ↑ The event was visualized in telefilm, Ghazi Shaheed in 1998 during the climax of its script.

- ↑ Transition to triumph: history of the Indian Navy, 1965-1975 By G. M. Hiranandani

- ↑ Staff writer (24 December 2006). "India did not sink Ghazi: Pak commander - Times of India". The Times of India. Times of India, 2006. Times of India. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ Shabbir, Usman. "List of Gallantry Awardees – PN Officers/CPOs/Sailors « PakDef Military Consortium". pakdef.org. pakdef.org. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ Lodhi, Lieutenant-General S.F.S. (January 2000). "An Agosta Submarine for Pakistan". www.defencejournal.com. Defence Journal, General Lodhi. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- 1 2 Shabbir, Usman. "Their Name Liveth for Ever More « PakDef Military Consortium". pakdef.org. Usman Shabbir, PakDef. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ See Albacora-class submarine

- ↑ "Ghazi Shaheed". Ptv Classics. 13 November 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ↑ Oversight PNS Zafar

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

External links

- Pictures of the Ghazi

- The PNS Ghazi incident as described in an article from "The Liberation Times"

- India Defence report on the Ghazi's sinking

- rediff news article

- Hindu E-News paper article

- Neutral Source from Russian site

- Record of kills by Indian Navy in 1971 War

- Tribune's E-news article

- Orbat article on PNS Ghazi