Panchen Lama

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Practices and attainment |

|

History and overview |

|

The Panchen Lama (Tibetan: པན་ཆེན་བླ་མ, Wylie: pan chen bla ma THL Penchen Lama), or Panchen Erdeni (Tibetan: པན་ཆེན་ཨེར་ཏེ་ནི། , THL Penchen Erténi), is the highest ranking lama after the Dalai Lama in the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism, the lineage which controlled western Tibet from the 16th century until the Battle of Chamdo and the subsequent 1959 Tibetan uprising.

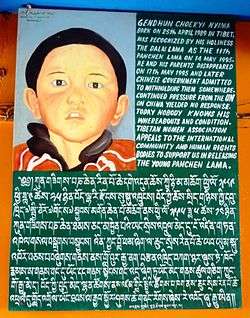

There were two candidates for the present (11th) incarnation of the Panchen Lama: one, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima, was recognized by the 14th Dalai Lama on 14 May 1995; the alternative, Gyaincain Norbu, was selected by the Government of the People's Republic of China. Gedhun Choekyi Nyima vanished from the public eye shortly after being named at age six. It has been claimed that Gedhun had been taken into protective custody from those that would spirit him into exile and is now held in captivity against the wishes of the Tibetan people, whereas the Chinese government states that he is living a "normal" private life.[1] Tibetans and human rights groups continue to campaign for his release.[2]

History

The successive Panchen Lamas form a tulku reincarnation lineage which are said to be the incarnations of Amitābha. The title, meaning "Great Scholar", is a Tibetan contraction of the Sanskrit paṇḍita (scholar) and the Tibetan chenpo (great). The Panchen Lama traditionally lived in Tashilhunpo Monastery in Shigatse. From the name of this monastery, the Europeans referred to the Panchen Lama as the Tashi-Lama (or spelled Tesho-Lama or Teshu-Lama).[3][4] [5]

The recognition of Panchen Lamas has always been a matter involving the Dalai Lama.[6][7] Choekyi Gyaltsen, 10th Panchen Lama, himself declared, as cited by an official Chinese review that "according to Tibetan tradition, the confirmation of either the Dalai or Panchen must be mutually recognized."[8] The involvement of China in this affair is seen by some as a political ploy to try to gain control over the recognition of the next Dalai Lama (see below), and to strengthen their hold over the future of Tibet and its governance. China claims however, that their involvement does not break with tradition in that the final decision about the recognition of both the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama traditionally rested in the hands of the Chinese emperor. For instance, after 1792, the Golden Urn was thought to have been used in selecting the 10th, 11th and 12th Dalai Lamas;[9] but the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, has more recently claimed that this was only really used in selection of the 11th, and that in the other cases it was only used to humour the Chinese to confirm a selection that had already been made by traditional methods.[10]

A controversy existed between the Tibetan government and supporters of Choekyi Gyaltsen. Ma Bufang patronized Choekyi Gyaltsen and the non-Gelug schools against the Dalai Lama. Qinghai served as a "sanctuary" for these groups, Ma Bufang allowed Kumbum Monastery to be totally self-governed by the Panchen Lama.[11] The 10th Panchen Lama, who was exiled from Tibet by the Dalai Lama's government, wanted to seek revenge by leading an army against Tibet in September 1949. He asked for help from Ma Bufang.[12] Ma cooperated with the Panchen Lama against the Dalai Lama's regime in Tibet. The Panchen Lama stayed in Qinghai. Ma tried to persuade the Panchen Lama to come with the Kuomintang government to Taiwan when the Communist victory approached, but the Panchen Lama decided to defect to the Communists instead. The Panchen Lama, unlike the Dalai Lama, sought to exert control in decision making.[13][14]

Relation to the Dalai Lama lineage

The Panchen Lama bears part of the responsibility or the monk-regent for finding the incarnation of the Dalai Lama, and vice versa.[15] This has been the tradition since the 5th Dalai Lama, recognized his teacher Lobsang Choekyi Gyaltsen as the Panchen Lama of Tashilhunpo. With this appointment, Lobsang Choekyi Gyaltsen's three previous incarnations were posthumously recognised as Panchen Lamas. The "Great Fifth" also recognized Lobsang Yeshe, 5th Panchen Lama. The 7th Dalai Lama recognized Lobsang Palden Yeshe, 6th Panchen Lama, who in turn recognized the 8th Dalai Lama. Similarly, the Eighth Dalai Lama recognised Palden Tenpai Nyima, 7th Panchen Lama.[16]

The 10th Panchen Lama became the most important political and religious figure in Tibet following the 14th Dalai Lama's escape to India in 1959. In April, 1959 the 10th Panchen Lama sent a telegram to Beijing expressing his support for suppressing the 1959 rebellion. “He also called on Tibetans to support the Chinese government.”[17] In 1962, he wrote the 70,000 Character Petition detailing famine and abuses of power by Chinese leaders in Tibet and discussed it with Zhou Enlai.[18] However, in 1964, he was imprisoned.[19] His situation worsened when the Cultural Revolution began. The Chinese dissident Wei Jingsheng wrote in March 1979 a letter denouncing the inhumane conditions of the Chinese Qincheng Prison where the late Panchen Lama was imprisoned.[20] In October 1977, he was released but held under house arrest in 1982. In 1979, he married a Han Chinese woman and in 1983 they had a daughter,[21] which is not unusual as several Gelug high lamas (Gelek Rinpoche in the US and Dagyab Rinpoche in Germany, among others) have chosen a layman's lifestyle, both inside China and in exile; also, the 6th Dalai Lama, also a Gelugpa, renounced his monk vows and led not only a layman's but a playboy's lifestyle, but still is highly revered by Tibetans. In 1989, the 10th Panchen Lama died suddenly in Shigatse at the age of 51 shortly after giving a speech critical of the Chinese neglect for the religion and culture of the Tibetans. His daughter, now a young woman, is Yabshi Pan Rinzinwangmo, better known as "Renji".[22]

Lineage

In the lineage of the Tibetan Panchen Lamas there were considered to be four Indian and three Tibetan incarnations of Amitabha before Khedrup Gelek Pelzang, 1st Panchen Lama. The lineage starts with Subhuti, one of the original disciples of Gautama Buddha. Gö Lotsawa is considered to be the first Tibetan incarnation of Amitabha in this line.[23][24]

Political significance

Monastic figures had historically held important roles in the social and makeup of Tibet, and though these roles have diminished since 1959, many Tibetans continue to regard the Panchen Lama as a significant political, as well as spiritual figure due to the role he traditionally plays in selecting the next Dalai Lama. The political significance of the role is also utilised by the Chinese state.[25] Tibetan support groups have argued that the Chinese government seeks to install its own choice of Dalai Lama when Tenzin Gyatso, the current Dalai Lama, dies and that for this reason the Dalai Lama's choice of Panchen Lama, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima went missing at the age of six, to be replaced by the Chinese state's choice, Gyaincain Norbu. If this tactic is successful, the Chinese government will give the title of Dalai Lama to the son of a loyal ethnic Tibetan Communist party member and it will pressure Western governments to recognize its boy, and not the boy chosen by Lamas in India, as the head of Tibetan Buddhism.[26]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Philippe Naughton October 17, 2011 10:46AM (2011-09-30). "China Says Missing Panchen Lama Living In Tibet". London: Timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ↑ "Learn More". Free the Panchen Lama. 1989-04-25. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ↑ "Pro-British Tashi Lama Succeeds Ousted Dalai Lama. British to Leave Lhasa" (PDF). New York Times. Sep 1901. Retrieved April 2011. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Fort William-India House correspondence: In the index, “Tashi Lama. See Teshu Lama”. and “Teshu Lama (Teshi Lama, Tesho Lama)”.

- ↑ "Definition for "Lama"". Oxford English Dictionary Online.

The chief Lamas[…]of Mongolia [are called] Tesho- or Teshu-lama.

- ↑ et :Ya Hanzhang, Biographies of the Tibetan Spiritual Leaders Panchen Erdenis. Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1987. pg 350.

- ↑ When the sky fell to earth Archived November 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Panchen-lama. 1988. "On Tibetan Independence." China Reconstructs (now named China Today) (January): Vol. 37, No. 1. pp 8–15.

- ↑ Goldstein 1989

- ↑ Reincarnation - statement by his holiness the Dalai Lama

- ↑ Santha Rama Rau (1950). East of home. Harper. p. 122.

- ↑ "EXILED LAMA, 12, WANTS TO LEAD ARMY ON TIBET". Los Angeles Times. 6 Sep 1949. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- ↑ Melvyn C. Goldstein (2009). A History of Modern Tibet: The Calm Before the Storm: 1951-1955, Volume 2. University of California Press. pp. 272, 273. ISBN 0-520-25995-5. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Isabel Hilton (2001). The Search for the Panchen Lama. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 110. ISBN 0-393-32167-3.

- ↑ Kapstein (2006), p. 276

- ↑ Appeal For Chatral Rinpoche's Release, from the website of "The Office of Tibet, the official agency of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in London"

- ↑ Lee Feigon, Demystifying Tibet, page 163.

- ↑ Kurtenbach, Elaine (February 11, 1998). "1962 report by Tibetan leader tells of mass beatings, starvation". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2001-07-21. Retrieved 2016-04-18.

- ↑ Richard R. Wertz. "Exploring Chinese History :: East Asian Region :: Tibet". Ibiblio.org. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ↑ "Excerpts from Qincheng: A Twentieth Century Bastille, published in Exploration". Weijingsheng.org. March 1979. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ↑ BUDDHA'S DAUGHTER: A YOUNG TIBETAN-CHINESE WOMAN Archived March 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Hilton, Isabel (March 29, 2004). "The Buddha's Daughter: Interview with Yabshi Pan Rinzinwangmo". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Stein 1972, p. 84

- ↑ Das, Sarat Chandra. Contributions on the Religion and History of Tibet (1970), p. 82. Manjushri Publishing House, New Delhi. First published in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. LI (1882).

- ↑ "Afp Article: Tibet'S Panchen Lama, Beijing'S Propaganda Tool". Google.com. 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

- ↑ O'Brien, Barbara (2011-03-11). "Dalai Lama Steps Back But Not Down". London, England: Guardian. Retrieved 2011-10-17.

Sources

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State (1989) University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06140-8

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama (1997) University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21951-1

- Kapstein, Matthew T. (2006). The Tibetans. Blackwell Publishing. Oxford, U.K. ISBN 978-0-631-22574-4.

- Stein, Rolf Alfred. Tibetan Civilization (1972) Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0901-7

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panchen Lama. |

- Free the Panchen Lama, a campaigns website for the Panchen Lama's release

- Tibet Society UK - The Background To The Panchen Lama from http://www.tibet-society.org.uk/

- China Tibetology No. 03, a series of articles from tibet.cn explaining the Chinese government's position on the search of reincarnations of the Panchen Lama.

- Tibet's missing spiritual guide, a May 2005 article from BBC News

- 11th Panchen Lama of Tibet, a website about Gedhun Choekyi Nyima