Sơn Tây Campaign

| Son Tay Campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Tonkin Campaign | |||||||

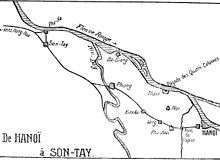

Map of Son Tay, December 1883 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9,000 soldiers, 6 gunboats |

3,000 Black Flag soldiers 7,000 Vietnamese soldiers 2,000 Chinese soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 83 killed, 320 wounded | 900 killed, around 1,000 wounded (mostly Black Flag Army) | ||||||

- Not to be confused with Tây Sơn Rebellion

The Son Tay Campaign (11 December 1883 to 17 December 1883) was a campaign fought by the French to capture the strategically important city of Son Tay in Tonkin (northern Vietnam) from Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army and allied contingents of Vietnamese and Chinese troops. The campaign was one of several clashes between the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps and the Black Flag Army during the Tonkin Campaign (1883–1886), and took place during the period of undeclared hostilities that preceded the Sino-French War (August 1884–April 1885).[1]

Background

Following the defeat and death of the French naval captain Henri Rivière at the Battle of Paper Bridge on 19 May 1883 at the hands of Liu Yongfu and the Black Flag Army, the French government sent substantial reinforcements to Tonkin. General Alexandre-Eugène Bouët (1833–87), Rivière's successor, attempted to destroy the Black Flag Army in the summer and autumn of 1883, but although the Black Flags suffered substantial losses in the Battle of Phu Hoai (15 August) and the Battle of Palan (1 September), the French failed to defeat them decisively. In October 1883 command of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps was given to Admiral Amédée Courbet. The French now prepared for a major offensive at the end of the year to annihilate the Black Flags, and tried to persuade China to withdraw its support for Liu Yongfu, while attempting to win the support of the other European powers for the projected offensive. Jules Ferry and the French foreign minister Paul-Armand Challemel-Lacour met a number of times in the summer and autumn of 1883 with the Chinese minister Marquis Zeng Jize in Paris, but these diplomatic discussions proved abortive.[2] The Chinese stood firm, and refused to withdraw substantial garrisons of Chinese regular troops from Son Tay, Bac Ninh and Lang Son, despite the likelihood that they would be shortly engaged in battle against the French. In turn, the French consolidated their hold on the Delta by establishing posts at Quang Yen, Hung Yen and Ninh Binh. In December 1883 Admiral Courbet was authorised by Ferry's government to attack Son Tay. The French cabinet accepted that an attack on Liu Yongfu would probably result in an undeclared war with China, but calculated that a quick victory in Tonkin would force the Chinese to accept a fait accompli.[3]

The forces

Son Tay lay a few kilometres to the south of the Red River. The town was protected by a kite-shaped pentagonal curtain wall just over eleven feet high, with three short sides facing roughly east and two long sides converging to a sharp point to the west of the town. The curtain wall was enclosed on all five sides by a wide, deep moat filled with water and by a tall bamboo palisade. Even if an attacker crossed these obstacles and breached the curtain wall, he still had to capture the central citadel of Son Tay. The citadel, built by Vietnamese engineers on the model of the French citadels of Cochinchina, lay at the heart of the town. It was square-shaped, and its walls were 300 metres long. It was dominated by a watchtower 18 metres high. According to the reports that the French had received, there were at least a hundred cannon in battery behind the defences.[4]

To remain in contact with the flotilla, the French were bound to approach Son Tay from the east, with their right flank lying on the Red River. In theory, they could march past Son Tay on its northern side, squeezing their columns between the town and the river, and deploy for an attack on the vulnerable acute angle where the two long walls met to the west of the town. However, the defenders had done their best to ensure that they would never get there. The dyke paths leading to Son Tay from the Day River converged at the village of Phu Sa, just to the northeast of the town. The Black Flags had hired European engineers to convert Phu Sa into an impregnable strongpoint. Water-filled ditches, bamboo palisades and trenches surrounded a central redoubt, and subsidiary defences hampered the approach to the main position. From the Phu Sa strongpoint, the Black Flags had an excellent field of fire both out to the east, from where the initial French attack was likely to come, and north to the Red River. To deploy to the north and west of Son Tay, the French would first have to capture Phu Sa. This would not be an easy task, as Liu Yongfu had strongly garrisonned the village and packed it with cannon. The cannon were dug in beneath casemates, making them a difficult target to knock out.[5]

Son Tay was defended by 3,000 veteran soldiers of the Black Flag Army under the command of Liu Yongfu, around 7,000 Vietnamese troops of indifferent quality under the command of Prince Hoang Ke Viem, and a contingent of 1,000 Chinese troops under the command of Tang Zhiong (唐炯). Hoang Ke Viem's Vietnamese garrisonned the citadel, and the Chinese were deployed inside Sontay. The curtain wall and the outwork of Phu Sa were held by Liu Yongfu's Black Flags. Neither the Vietnamese nor the Chinese contingents would play any significant role in the battle, which was essentially a straight fight between the French and the Black Flags.

Admiral Amédée Courbet led the bulk of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps to Son Tay. The French deployed around 9,000 men for the campaign, organised into two columns under the respective command of Colonel Belin and Colonel Bichot.[6] Belin's column, 3,300 men strong, consisted of two Turco battalions (chefs de bataillon Jouneau and Letellier), one marine infantry battalion (chef de bataillon Roux) with an attached company of Cochinchinese riflemen, the 1st Foreign Legion Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Donnier), 800 Tonkinese riflemen (chef de bataillon Bertaux-Levillain) and three marine artillery batteries.[Note 1] Bichot's column consisted of three marine infantry battalions (chefs de bataillon Chevallier, Dulieu and Reygasse), each with an attached company of Cochinchinese riflemen, a battalion of fusiliers-marins (capitaine de frégate Laguerre), three marine artillery batteries and a 65-millimetre naval battery.[Note 2]

The campaign

Both French columns set off from Hanoi at dawn on 11 December 1883. Courbet had told nobody the objective of the expedition, and many of the combatants had been expecting to march against Bac Ninh, which had been occupied by around 20,000 troops of China's Guangxi Army in the autumn of 1882. Belin's column marched overland to the Day River from Hanoi, while Bichot's column was transported up the Red River by six French gunboats of the Tonkin Flotilla (Pluvier, Trombe, Éclair, Hache, Mousqueton and Yatagan) and several steam launches, junks and tugs. On the afternoon of 11 December Bichot's column went ashore on the western bank of the Day River and secured a passage for Belin's slower-moving column. Meanwhile, Belin's column marched over Paper Bridge and through the villages of Phu Hoai, Kien Mai and Phong, recrossing the battlefields of 19 May and 15 August, and reached the Day River without incident. On 13 December both columns met five kilometres from the forward defences of Son Tay. Belin's men needed rest, and Courbet postponed the battle for Son Tay to the following day.[7]

The battle for Son Tay

The battle to take Son Tay was the fiercest engagement the French had yet fought against the Black Flags. The Black Flags fought ferociously to defend the city. Early in the afternoon of 14 December the French advanced from the east on the Phu Sa positions, beating off a Black Flag sortie against their right flank. Artillery was brought up, and in a two-hour bombardment the Black Flag guns at Phu Sa were gradually silenced. Later in the afternoon Roux and Chevallier's battalions captured the forward Black Flag positions at Phu Sa, but attempts to exploit this success failed. Godinet's company of Jouneau's Turco battalion and Cuny's company of Roux's marine infantry battalion assaulted the central redoubt, but were thrown back with heavy casualties. By nightfall the French were still stalled in front of Phu Sa. French casualties on 14 December were 68 killed (including 3 officers) and 249 wounded (including 17 officers). Nearly half these casualties were sustained by Jouneau's Turco battalion, which was unable to play any further role in the battle. In one day Courbet had lost more men than his predecessors Rivière and Bouët had done in all their battles put together.

Hoping to exploit Courbet's defeat, Liu Yongfu attacked the French lines the same night, but the Black Flag attack also failed disastrously. Liu Yongfu lost so many men in this counterattack that he was obliged to abandon the Phu Sa positions and withdraw into the fortified perimeter of Son Tay. After resting his troops on 15 December, Courbet assaulted the defences of Son Tay from the northwest on the afternoon of 16 December. This time the attack was thoroughly prepared by artillery, and delivered only after the defenders had been worn down. To hearten his troops, Courbet set an example of the utmost personal courage, riding forward to a position well within range of the Black Flag fire. At 5 p.m. Donnier's Foreign Legion battalion and Laguerre's fusiliers-marins captured the western gate of Son Tay and fought their way into the town. Liu Yongfu's garrison withdrew to the citadel, and evacuated Son Tay under cover of darkness several hours later. On the morning of 17 December the French stitched together an enormous tricolour flag from strips of cloth torn from captured Black Flag banners and hoisted it over the citadel of Son Tay while Courbet made a triumphal entry on horseback.[8]

Order of the day

On 17 December 1883 Courbet issued the following order of the day to the soldiers and sailors of the expeditionary corps:

Les forts de Phu-Xa et la citadelle de Son-Tay dont désormais illustrés par votre vaillance. Vous avez combattu, vous avez vaincu un ennemi redoutable. Vous avez montré une fois de plus au monde entier que la France peut toujours compter sur ses enfants. Soyez fiers de vos succès. Ils assurent la pacification du Tonkin.[9]

(The forts of Phu Sa and the citadel of Son Tay will henceforth be famed for your valour. You have fought and conquered a formidable enemy. You have once again shown the whole world that France can always count upon her children. Be proud of your successes. They have ensured the pacification of Tonkin.)

Significance

Courbet had achieved his objective, but at considerable cost. Total French casualties during the two days of fighting amounted to 83 dead and 320 wounded. The dead or mortally-wounded officers included Captain Godinet of Jouneau’s Algerian Rifle battalion, Captains Doucet and Cuny and Lieutenant Clavet of the marine infantry, and Captain Mehl of Donnier’s Legion battalion. Twenty-two other officers were wounded.[10] One jaundiced French officer commented, 'Admiral Courbet took Son Tay as you would expect a sailor to do: by boarding.'[11]

According to reports later received by the French, Chinese and Vietnamese casualties at Son Tay had been heavy: 900 dead and around 1,000 wounded. Nearly all these casualties were suffered by Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army.[12] The fighting at Son Tay took a terrible toll of the Black Flags, and in the opinion of the British observer William Mesny broke them once and for all as a serious fighting force.

The disproportionate sacrifices made by the Black Flag Army at Son Tay had important consequences. Liu Yongfu felt that he had been deliberately left to bear the brunt of the fighting by his Chinese and Vietnamese allies, and determined never again to expose his troops so openly. After the fall of Son Tay Liu retreated with the Black Flag Army to Bac Ninh, but made little attempt to coordinate the movements of the Black Flag Army with those of the Chinese forces at Bac Ninh. The absence of the Black Flags from the battlefield was an important factor in the defeat of China's Guangxi Army in the Bac Ninh campaign in March 1884.

Notes

- ↑ Jouneau’s Turco battalion was the 1st Battalion, 3rd Algerian Rifle Regiment (Captains Godinet, Noirot, Carles and Massip). Letellier’s Turco battalion was the 2nd Battalion, 1st Algerian Rifle Regiment (Captains Servant, Cannebotin, Omar ben Chaouch and Ligrisse). Roux’s marine infantry battalion consisted of the 25th, 26th and 30th Companies, 4th Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Drouin, Bécourt and Martellière) and the 4th Annamese Rifle Company (Captain Serre de Bazaugour). Donnier's Legion battalion was the 1st Battalion, 1st Foreign Legion Regiment (Captains Conte, Moulinay, Bergounioux and Broussier). The column’s artillery included the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Marine Artillery Batteries bis (Captains Régis, Dupont and Roussel).

- ↑ Chevallier’s battalion consisted of the 25th, 28th and 29th Companies, 1st Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Poulnot, Boulle and Durruthy) and the 1st Annamese Rifle Company (Captain de Beauquesne). Dulieu’s battalion consisted of the 21st, 22nd and 23rd Companies, 2nd Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Bauche, Cuny and Leverger) and the 2nd Annamese Rifle Company (Captain Doucet). Reygasse’s battalion consisted of the 26th, 29th and 33rd Companies, 3rd Marine Infantry Regiment (Captains Poisot, Noble and Trilha) and the 3rd Annamese Rifle Company (Captain Berger). The column’s artillery included the 4th, 5th and 6th Marine Artillery Batteries bis (Captains Roperh, Péricaud and Dudraille) and lieutenant de vaisseau Amelot’s naval battery.

Footnotes

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 170–77; Histoire militaire, 68–72

- ↑ Eastman, 85–7

- ↑ Lonlay, 111–16; Duboc, 207; Huard, 164–70; Sarrat, 108–10

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 172–4; Histoire militaire, 69

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 172–4; Histoire militaire, 69

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 69

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 69

- ↑ Bastard, 211–28; Cahu, 40–64; Challan de Belval, 139–41; Lonlay, 133–80; Grisot and Coulombon, 417–28; Huard, 180–7 and 202–31; Nicolas, 300–19; Sarrat, 110–17

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 72

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 71

- ↑ Huguet, page number to be supplied

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 71

References

- Bastard, G., Défense de Bazeilles, suivi de dix ans après au Tonkin (Paris, 1884)

- Cahu, T., L'amiral Courbet en Extrême-Orient: notes et correspondance (Paris, 1896)

- Challan de Belval, Au Tonkin 1884-1885: notes, souvenirs et impressions (Paris, 1904)

- Duboc, E., Trente cinq mois de campagne en Chine, au Tonkin (Paris, 1899)

- Eastman, L., Throne and Mandarins: China's Search for a Policy during the Sino-French Controversy (Stanford, 1984)

- Grisot and Coulombon, La légion étrangère de 1831 à 1887 (Paris, 1888)

- Huard, La guerre du Tonkin (Paris, 1887)

- Huguet, E, En colonne: souvenirs d'Extrême-Orient (Paris, 1888)

- Lonlay, D. de, Au Tonkin, 1883-1885 (Paris, 1886)

- Nicolas, V., Livre d'or de l'infanterie de la marine (Paris, 1891)

- Sarrat, L., Journal d'un marsouin au Tonkin, 1883-1886 (Paris, 1887)

- Thomazi, Histoire militaire de l’Indochine française (Hanoi, 1931)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)