Turkestan

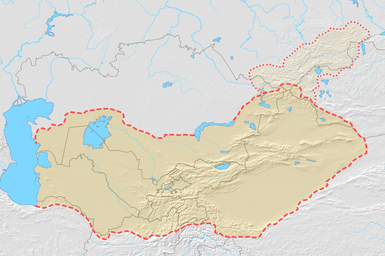

Turkestan, also spelled Turkistan, literally means "Land of the Turks" in Persian. It refers to an area in Central Asia between Siberia to the north and Tibet, India and Afghanistan to the south, the Caspian Sea to the west and Mongolia and the Gobi Destert to the east.

Etymology and terminology

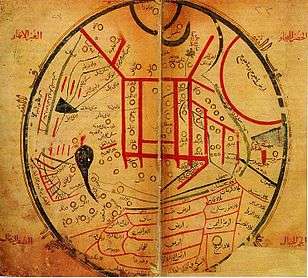

Of Persian origin (see -stan), the term "Turkestan" (ترکستان) has never referred to a single national state.[1] Muslim geographers first used the word to describe the place of Turkic peoples.[2]

Turkestan was used to describe any place where Turkic peoples lived.[1] Anatolia during Ottoman rule was referred to as Turkestan by Ottoman writers.

On their way southward during the conquest of Central Asia in the course of the 19th century, the Russians took the city of Turkestan (in present-day Kazakhstan) in 1864. Mistaking its name for that of the entire region, they adopted the name of "Turkestan" for their new territory.[2][3]

As of 2015, the term labels a region in Central Asia which is inhabited mainly by Turkic peoples, but the regions also contained peoples who were not Turkic, such as the Tajiks, and excluded some who were. It includes present-day Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Xinjiang (East Turkestan or Chinese Turkestan).[4][5]Often, the Turkic regions of Afghanistan and Russia (Tatarstan and parts of Siberia) are included as well.

History

The history of Turkestan dates back to at least the third millennium BC. Many artifacts were produced in that period, and much trade was conducted. The region was a focal point for cultural diffusion, as the Silk Road traversed it. Turkestan covers the area of Central Asia and acquired its "Turkic" character from the 4th to 6th centuries AD with the incipient Turkic expansion.

Turkic sagas, such as the Ergenekon legend, and written sources such as the Orkhon Inscriptions state that Turkic peoples originated in the nearby Altai Mountains, and, through nomadic settlement, started their long journey westwards. Huns conquered the area after they conquered Kashgaria in the early 2nd century BC. With the dissolution of the Huns' empire, Chinese rulers took over Eastern Turkestan.[6] Arab forces captured it in the 8th century. The Persian Samanid dynasty subsequently conquered it and the area experienced economic success.[6] The entire territory was held at various times by Turkic forces, such as the Göktürks until the conquest by Genghis Khan and the Mongols in 1220. Genghis Khan gave the territory to his son, Chagatai and the area became the Chagatai Khanate.[6] Timur took over the western portion of Turkestan in 1369 and the area became part of the Timurid Empire.[6] Eastern portion of Turkestan was also called Mogulistan, and continued to be ruled by descendants of Genghis Khan.

Overview

Known as Turan to the Persians, western Turkestan has also been known historically as Sogdiana, Ma wara'u'n-nahr (by its Arab conquerors), and Transoxiana by Western travellers. The latter two names refer to its position beyond the River Oxus when approached from the south, emphasizing Turkestan's long-standing relationship with Iran, the Persian Empires and the Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates.

Turkestan is roughly within the regions of Central Asia lying between Siberia on the north; Tibet, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran on the south; the Gobi Desert on the east; and the Caspian Sea on the west.[7] Oghuz Turks (also known as Turkmens), Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Khazars, Kyrgyz, Hazara and Uyghurs are some of the Turkic inhabitants of the region who, as history progressed, have spread further into Eurasia forming such Turkic nations as Turkey and Azerbaijan, and subnational regions like Tatarstan in Russia and Crimea in Ukraine. Tajiks and Russians form sizable non-Turkic minorities.

It is subdivided into Afghan Turkestan and Russian Turkestan in the West, and Xinjiang (previously Chinese Turkestan) in the East.

Chinese influence

A summary of Classical sources on the Seres (Greek and Roman name of China) (essentially Pliny and Ptolemy) gives the following account:

The region of the Seres is a vast and populous country, touching on the east the Ocean and the limits of the habitable world, and extending west nearly to Imaus and the confines of Bactria. The people are civilised men, of mild, just, and frugal temper, eschewing collisions with their neighbours, and even shy of close [conversation], but not averse to dispose of their own products, of which raw silk is the staple, but which include also silk stuffs, furs, and iron of remarkable quality.— Henry Yule, Cathay and the Way Thither

In the Persian epic Shahnameh, China and Turkestan are regarded as the same, and the Khan of Turkestan is called the Khan of Chin.[8][9]

Aladdin, an Arabic Islamic story which is set in China, may have been referring to Turkestan.[10]

Muslim writers like Marwazī wrote that Transoxania was a former part of China, retaining the legacy of Tang Dynasty's rule over Transoxania:

In ancient times all the districts of Transoxania had belonged to the kingdom of China [Ṣīn], with the district of Samarqand as its centre. When Islam appeared and God delivered the said district to the Muslims, the Chinese migrated to their [original] centers, but there remained in Samarqand, as a vestige of them, the art of making paper of high quality. And when they migrated to Eastern parts their lands became disjoined and their provinces divided, and there was a king in China and a king in Qitai and a king in Yugur.— Marwazī

Muslim writers viewed the Khitai, the Gansu Uighur kingdom and Kashgar as all part of "China" culturally and geographically, with the Muslims in Central Asia retaining the legacy of Chinese rule in Central Asia by using titles such as "Khan of China" (تمغاج خان) (Tamghaj Khan or Tawgach) in Turkic and "the King of the East in China" (ملك المشرق (أو الشرق) والصين) (malik al-mashriq (or al-sharq) wa'l-ṣīn) in Arabic, which were titles of the Muslim Qarakhanid rulers and their Qarluq ancestors.[11][12]

The title Malik al-Mashriq wa'l-Ṣīn was bestowed by the 'Abbāsid Caliph upon the Tamghaj Khan, the Samarqand Khaqan Yūsuf b. Ḥasan. Afterwards, coins and literature had the title Tamghaj Khan appear on them, which continued to be used by the Qarakhanids, the Transoxania-based Western Qarakhanids and some Eastern Qarakhanid monarchs. Therefore, the Kara-Khitan (Western Liao)'s usage of Chinese things such as Chinese coins, the Chinese writing system, tablets, seals, Chinese art and other items from Chinese culture such as porcelein, mirrors, and jade was designed to appeal to the local Central Asian Muslim population, since the Muslims in the area regarded Central Asia as former Chinese territories and viewed connections with China as prestigious. Western Liao's rule over Muslim Central Asia reinforced these Muslims' view that Central Asia was a Chinese territory. For example, Turkestan and Chīn (China) were identified with each other by Fakhr al-Dīn Mubārak Shāh, with China being identified as the country where the cities of Balāsāghūn and Kashghar were located.[13]

The Liao Chinese traditions and the Qara Khitai's clinging helped the Qara Khitai avoid Islamization and conversion to Islam. The Qara Khitai used Chinese and Central Asian features in their administrative system.[13]

Although in modern Urdu Chin means China, Chin referred to Central Asia in Muhammad Iqbal's time, which is why Iqbal wrote that "Chin is ours" (referring to the Muslims) in his song Tarana-e-Milli.[14]

The Tang Chinese reign over Qocho and Turfan and the Buddhist religion left a lasting legacy upon the Buddhist Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho with the Tang presented names remaining on the more than 50 Buddhist temples with Emperor Tang Taizong's edicts stored in the "Imperial Writings Tower " and Chinese dictionaries like Jingyun, Yuian, Tang yun, and da zang jing (Buddhist scriptures) stored inside the Buddhist temples and Persian monks also maintained a Manichaean temple in the Kingdom., the Persian Hudud al-'Alam uses the name "Chinese town" to call Qocho, the capital of the Uyghur kingdom.[15]

The Turfan Buddhist Uighurs of the Kingdom of Qocho continued to produce the Chinese Qieyun rime dictionary and developed their own pronunciations of Chinese characters, left over from the Tang influence over the area.[16]

The modern Uyghur linguist Abdurishid Yakup pointed out that the Turfan Uyghur Buddhists studied the Chinese language and had Chinese books such as Qianziwen (the thousand character classic) and Qieyun *(a rime dictionary) and it was written that "In Qocho city were more than fifty monasteries, all titles of which are granted by the emperors of the Tang dynasty, which keep many Buddhist texts as Tripitaka, Tangyun, Yupuan, Jingyin etc." [17]

In Central Asia the Uighurs viewed the Chinese script as "very prestigious" so when they developed the Old Uyghur alphabet, based on the Syriac script, they deliberately switched it to vertical like Chinese writing from its original horizontal position in Syriac.[18]

The last major victory of Arabs in Central Asia occurred at the Battle of Talas (751). The Tibetan Empire was allied to the Arabs during the battle.[19][20][21][22][23] Because the Arabs did not proceed to Xinjiang at all, the battle was of no importance strategically, and it was An Lushan's rebellion which ended up forcing the Tang Chinese out of Central Asia.[24][25] Despite the conversion of some Karluk Turks after the Battle of Talas, the majority of Karluks did not convert to Islam until the mid 10th century, when they established the Kara-Khanid Khanate.[22][23][26][27][28][29] This was long after the Tang dynasty was gone from Central Asia.

Barthold states that the Islamic rule over Transoxiana was secured at the Battle of Talas. Turks had to wait two and a half centuries before reconquering Transoxiana when the Karakhanids reconquered the city of Bukhara in 999. Professor Denis Sinor said that it was interference in the internal affairs of the Western Turkic Khaganate which ended Chinese supremacy in Central Asia, since the destruction of the Western Khaganate rid the Muslims of their greatest opponent, and it was not the Battle of Talas which ended the Chinese presence.[30]

See also

References

- 1 2 Gladys D. Clewell, Holland Thompson, Lands and Peoples: The world in color, Volume 3, page 163. Excerpt: Never a single nation, the name Turkestan means simply the place of Turkish peoples.

- 1 2 Central Asian review by Central Asian Research Centre (London, England), St. Antony's College (University of Oxford). Soviet Affairs Study Group, Volume 16, page 3. Excerpt: The name Turkestan is of Persian origin and was apparently first used by Persian geographers to describe "the country of the Turks". It was revived by the Russians as a convenient name for the governorate-general created in 1867 and the terms Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, etc. were not used until after 1924.

- ↑ Annette M. B. Meakin, In Russian Turkestan: a garden of Asia and its people, page 44. Excerpt: On their way southward from Siberia in 1864, the Russians took it, and many writers affirm that, mistaking its name for that of the entire region, they adopted the appellation of "Turkestan" for their new territory. Up to that time, they assure us Khanates of Bokhara, Khiva and Kokand were known by these names alone.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica: Turkistan. Retrieved: 24 August 2009.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionaries, Oxford University Press: Turkestan. Retrieved: 26 May 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Turkistan", Encyclopædia Britannica 2007 Ultimate Reference Suite.

- ↑ Encyclopadea Britannica. Turkistan retrieved-18 march,2010

- ↑ Bapsy Pavry (19 February 2015). The Heroines of Ancient Persia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-1-107-48744-4.

- ↑ Bapsy Pavry Paulet, Marchioness of Winchester (1930). The Heroines of Ancient Persia: Stories Retold from the Shāhnāma of Firdausi. With Fourteen Illustrations. The University Press. p. 86.

- ↑ Moon, Krystyn (2005). Yellowface. Rutgers University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-8135-3507-7.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Schluessel, Eric T. (2014). "The World as Seen from Yarkand: Ghulām Muḥammad Khān's 1920s Chronicle Mā Tīṭayniŋ wā qiʿasi" (PDF). TIAS Central Eurasian Research Series (9). NIHU Program Islamic Area Studies: 13. ISBN 978-4-904039-83-0. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- 1 2 Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Although "Chin" refers to China in modern Urdu, in Iqbal's day it referred to Central Asia, coextensive with historical Turkestan. See also, Iqbal: Tarana-e-Milli, 1910. Columbia University, Department of South Asian Studies.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ TAKATA, Tokio. "The Chinese Language in Turfan with a special focus on the Qieyun fragments" (PDF). Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University: 7–9. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ Abdurishid Yakup (2005). The Turfan Dialect of Uyghur. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 180–. ISBN 978-3-447-05233-7.

- ↑ Liliya M. Gorelova (1 January 2002). Manchu Grammar. Brill. p. 49. ISBN 978-90-04-12307-6.

- ↑ Bulliet & Crossley & Headrick & Hirsch & Johnson 2010, p. 286.

- ↑ Bulliet 2010, p. 286.

- ↑ Chaliand 2004, p. 31.

- 1 2 Wink 2002, p. 68.

- 1 2 Wink 1997, p. 68.

- ↑ ed. Starr 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ Millward 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Lapidus 2012, p. 230.

- ↑ Esposito 1999, p. 351.

- ↑ Lifchez & Algar 1992, p. 28.

- ↑ Soucek 2000, p. 84.

- ↑ Sinor 1990, p. 344.

Further reading

- V.V. Barthold "Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion" (London) 1968 (3rd Edition)

- René Grousset "L'empire des steppes" (Paris) 1965

- David Christian "A History Of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia" (Oxford) 1998 Vol.I

- Svat Soucek "A History of Inner Asia" (Cambridge) 2000

- Vasily Bartold "Работы по Исторической Географии" (Moscow) 2002

- English translation: V.V. Barthold "Work on Historical Geography" (Moscow) 2002

- Baymirza Hayit. “Sowjetrußische Orientpolitik am Beispiel Turkestan.“ Köln-Berlin: Kiepenhauer & Witsch, 1956

- Hasan Bülent Paksoy Basmachi: Turkestan National Liberation Movement

- The Arts and Crafts of Turkestan (Arts & Crafts) by Johannes Kalter.

- The Desert Road to Turkestan (Kodansha Globe) by Owen Lattimore.

- Turkestan down to the Mongol Invasion. by W. BARTHOLD.

- Turkestan and the Fate of the Russian Empire by Daniel Brower.

- Tiger of Turkestan by Nonny Hogrogian.

- Turkestan Reunion (Kodansha Globe) by Eleanor Lattimore.

- Turkestan Solo: A Journey Through Central Asia, by Ella Maillart.

- Baymirza Hayit. “Documents: Soviet Russia's Anti-Islam-Policy in Turkestan.“ Düsseldorf: Gerhard von Mende, 2 vols, 1958.

- Baymirza Hayit. “Turkestan im XX Jahrhundert.“ Darmstadt: Leske, 1956

- Baymirza Hayit. “Turkestan Zwischen Russland Und China.“ Amsterdam: Philo Press, 1971

- Baymirza Hayit. “Some thoughts on the problem of Turkestan” Institute of Turkestan Research, 1984

- Baymirza Hayit. “Islam and Turkestan Under Russian Rule.” Istanbul:Can Matbaa, 1987.

- Baymirza Hayit. “Basmatschi: Nationaler Kampf Turkestans in den Jahren 1917 bis 1934.” Köln: Dreisam-Verlag, 1993.

- Mission to Turkestan: Being the memoirs of Count K.K. Pahlen, 1908–1909 by Konstantin Konstanovich Pahlen.

- Turkestan: The Heart of Asia by Curtis.

- Tribal Rugs from Afghanistan and Turkestan by Jack Frances.

- The Heart of Asia: A History of Russian Turkestan and the Central Asian Khanates from the Earliest Times by Edward Den Ross.

Bealby, John Thomas; Kropotkin, Peter (1911). "Turkestan". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 419–426.

Bealby, John Thomas; Kropotkin, Peter (1911). "Turkestan". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 419–426.