Cobble Hill Tunnel

|

Cobble Hill Historic District | |

|

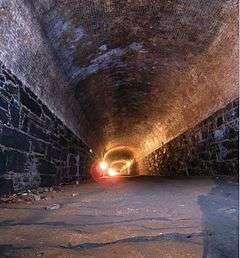

(2009) | |

| |

| Location | Brooklyn, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | Coordinates: 40°41′25.6″N 73°59′42.5″W / 40.690444°N 73.995139°W |

| Built | 1844 |

| Architect | Asa Stebbins |

| Architectural style | Roman, Italianate, Queen Anne |

| NRHP Reference # | 89001388[1] |

| Added to NRHP | September 7, 1989 |

The Cobble Hill Tunnel (popularly the Atlantic Avenue Tunnel) of the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) is an abandoned railroad tunnel beneath Atlantic Avenue in downtown Brooklyn, New York City. When open, it ran for about 2,517 feet (767 m) between Columbia Street and Boerum Place. It is the oldest railway tunnel beneath a city street in North America that was fully devoted to rail.[2][3][4]

Construction and operation

Originally built as an open cutting, construction began in May 1844, and opened for use on December 3, 1844, but was not completely finished until late Spring 1845. It was built mainly to satisfy public demand for creation of a grade-separated right of way for the Brooklyn and Jamaica Railroad (later Long Island Rail Road) on its way to the South Ferry at the foot of Atlantic Street (later Atlantic Avenue), where passengers could catch ferries to Manhattan.[5] The construction of the cutting also lowered the LIRR's grade through Cobble Hill. Around five years after opening the cutting was roofed over, converting it into a tunnel.

In exchange for building the cutting, the City of Brooklyn granted the B&J permission to operate its steam locomotives on Atlantic Street west of Fifth Avenue (then Parmentier's Garden/Gowanus Lane), all the way to Brooklyn's South Ferry (the present location of Brooklyn's Pier 7). Prior to the cutting being built, the LIRR's western terminus was Atlantic Street at Clinton Street. Train cars were hauled by teams of horses along Atlantic Street from Clinton Street to Parmentier's Garden, where steam locomotives were attached. While the cutting was being built, the railroad operated to a temporary terminal at Pacific Street and Henry Street.

The Cobble Hill Tunnel was part of the first rail link between New York City and Boston, Massachusetts. The railroad connected Lower Manhattan via the South Ferry to Greenport on the North Fork of Long Island, where a ferry connected to Stonington, Connecticut, where a rail link continued to Boston. This avoided some difficult construction of bridges over the rivers of southern Connecticut. In 1848, the New York and New Haven Railroad Line was completed through Connecticut, providing a direct, faster rail connection from New York City to Boston. The Cobble Hill Tunnel and the Long Island Railroad remained the primary means of access to most of central Long Island from Manhattan and New York City. As originally built, the cutting was 21 feet (6.4 m) wide and 2,517 feet (767 m) long. Once roofed over the interior height of the newly-created tunnel was 17 feet (5.2 m).

The ends of the tunnel were sealed in the fall of 1861. The similar Murray Hill Tunnel on the New York and Harlem Railroad was built as an open cut around 1836, roofed over around the 1850s, and is now in use for automobile traffic.

Closure controversy

In 1861, the New York State Legislature voted to ban railroad locomotives from within the limits of the City of Brooklyn. A tax assessment was ordered on all property owners along Atlantic Street (today Atlantic Avenue), to defray the costs of the closure. It was undisclosed at the time that New York State Governor John A. King was a major shareholder in the Brooklyn and Jamaica Railroad (later the Long Island Rail Road) and therefore had a conflict of interest and stood to benefit by the compensation payments to the railroad from the tax assessment.

Dormancy

Walt Whitman wrote of the tunnel:[6]

The old tunnel, that used to lie there under ground, a passage of Acheron-like solemnity and darkness, now all closed and filled up, and soon to be utterly forgotten, with all its reminiscences; however, there will, for a few years yet be many dear ones, to not a few Brooklynites, New Yorkers, and promiscuous crowds besides. For it was here you started to go down the island, in summer. For years, it was confidently counted on that this spot, and the railroad of which it was the terminus, were going to prove the permanent seat of business and wealth that belong to such enterprises. But its glory, after enduring in great splendor for a season, has now vanished—at least its Long Island Railroad glory has. The tunnel: dark as the grave, cold, damp, and silent. How beautiful look earth and heaven again, as we emerge from the gloom! It might not be unprofitable, now and then, to send us mortals—the dissatisfied ones, at least, and that's a large proportion—into some tunnel of several days' journey. We'd perhaps grumble less, afterward, at God's handiwork.

In March 1916, the Bureau of Investigation suspected German terrorists were making bombs in the tunnel, and broke through the roof of the tunnel with jackhammers. They found nothing, installed an electric light, and resealed it. In the 1920s it was rumored used for both mushroom growing and bootleg whiskey stills even though there was no access into the main portion of the tunnel. It became an object of local folklore and legend. In 1936, the New York City Police Department unsuccessfully attempted to enter the tunnel, in order to look for the body of a hoodlum supposedly buried there. In 1941 it was rumored to have been inspected by the federal Works Progress Administration to determine its structural strength, but there is no evidence of this. A few years later, it was once again rumored to have been opened, this time by the FBI, in an unsuccessful search for spies; however, there is no evidence of this. During the late 1950s, it was sought by two rail historians, George Horn and Martin Schachne, but they did not gain access to the tunnel itself.

Rediscovery

Having fallen from public notice, the tunnel was rediscovered in 1980 by then 20-year-old Robert Diamond,[7] who entered from a manhole he located at Atlantic Avenue and Court Street, crawled a distance of 70 feet (21 m) underground through a filled-in section of tunnel less than two feet high, and located the bulkhead wall that sealed off the main portion of the tunnel. With the assistance of a Brooklyn Union Gas Co. (now National Grid) engineering crew, he then broke through the massive concrete bulkhead wall, which is several feet thick. Diamond thereby opened access to the main portion of the tunnel, and began to popularize the tunnel as an antiquity. He led tours of its interior[6] from 1982 until December 17, 2010,[8] when the Department of Transportation terminated his contract, citing safety concerns.[7] The tunnel has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since 1989.

The History Channel series Cities of the Underworld ran a segment ("New York's Secret Societies") on the tunnel in Fall 2008. The TV show Treasure Hunters used it in an episode.

See also

- Brooklyn Historic Railway Association

- Cobble Hill, Brooklyn

- Beach Pneumatic Transit

- Track 61 (New York City)

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Kings County, New York

References

Notes

- ↑ National Park Service (2008-04-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Hilger, James (March 23, 2009). "Notes from the Underground: The Secret Tunnels of Brooklyn". psfk.com. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ↑ Citynoise: Oldest Subway Tunnel in the World Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2009-04-08.

- ↑ According to the ForgottenNY.com website, the Park Avenue Tunnel is older, but was meant only for streetcars, not for true railways.

- ↑ "Events That Led to the Creation of the Atlantic Avenue Tunnel" (PDF). Brooklyn Historic Railway Association. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- 1 2 "Crossing Brooklyn LIRR Tunnel". Forgotten NY. Archived from the original on December 26, 2008. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- 1 2 Tunnel vision: how an obsessed explorer found and lost the world's oldest subway

- ↑ NBC.com

Further reading

- "The Atlantic Avenue Tunnel". Brooklynrail.net. Retrieved July 31, 2009.

- "Urban Underground Passageways An Historical Overview" (PDF). Brooklynrail.net. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- "Early Transit in New York City". NYSubway.org. Retrieved October 29, 2005.

- "The Atlantic Avenue Tunnel". New York City Subway Transit Scenes. Retrieved October 29, 2005.

- "Brooklyn Historic Railway Association and Atlantic Avenue Tunnel". Retrieved October 29, 2005.

- "A Long-Lost Tunnel in Brooklyn". LI History.com. Archived from the original on October 13, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- "Cobble Hill (Atlantic Avenue) Tunnel History". RapidTransit.net. Retrieved October 29, 2005.

- Joseph, Yonette (February 15, 2009). "The Tunnel Rats of Atlantic Avenue". NYTimes.com. Retrieved April 29, 2009.

- "The New York Moon – Undertone – Music video in the tunnel". nymoon.com. Retrieved May 20, 2009.