Minnesota Correctional Facility – Stillwater

|

Main entrance of the Minnesota Correctional Facility – Stillwater | |

| Location | Bayport, Minnesota, United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 45°1′40″N 92°47′20″W / 45.02778°N 92.78889°WCoordinates: 45°1′40″N 92°47′20″W / 45.02778°N 92.78889°W |

| Status | Operational |

| Security class | Level 4- "Close Custody" |

| Population | 1604 (as of August 22, 2015) |

| Opened | 1914 |

| Managed by | Minnesota Department of Corrections |

| Warden | Steve Hammer |

| Street address | 970 Pickett Street |

| City | Bayport, Minnesota |

| County | Washington County |

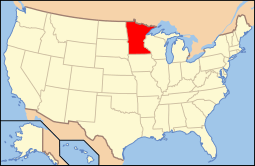

| State | Minnesota |

| ZIP code | 55003 |

| Country | United States |

| Website |

http://www.doc.state.mn.us/pages/index.php/facilities/adult-facilities/stillwater/ |

|

State Prison Historic District | |

| Area | 35 acres (14 ha) |

| Built | 1910–14, 1928 |

| Architect | Clarence H. Johnston, Sr. |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| NRHP Reference # | 86001574[1] |

| Added to NRHP | July 10, 1986 |

The Minnesota Correction Facility – Stillwater (MCF-STW) is a close custody (level 4) state prison for men in Bayport, Minnesota, United States. Built 1910–1914, it houses 1,600 inmates in seven different living areas. Additionally, approximately 100 inmates are housed in a nearby minimum security area. It replaced the original Minnesota Territorial Prison located just to the north in the city of Stillwater, Minnesota. Until recent expansion of the medium custody (level 3) Minnesota Correctional Facility – Faribault, MCF-STW was the state's largest facility by inmate population. A historic district consisting of 22 contributing properties was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1986 as the State Prison Historic District for having state-level significance in architecture. It was nominated for being one of the nation's earliest and most influential appearances of the "telephone pole" layout, with a large main hallway connecting each of the units, that was widely adopted by high-security prisons.[2] MCF-STW is noted for its award-winning publication The Prison Mirror, the oldest continuously-operated prison newspaper in the United States.[3]

History

In 2008 four inmates attempted to tunnel their way out. David Spaeth, Craig Friend, Andrew Salinas and Gonzalo Hernandez used pilfered tools, including an electric hammer drill, to tunnel approximately 25 feet. Their plan was thwarted when a corrections officer followed a power cord. Prison officials described the escape attempt as "sophisticated and complex."[4]

Programs

One of three Level 4 (Close) custody facilities in Minnesota, the prison hosts an industrial program, education programs, and the Atlantis chemical dependency treatment program. A small number of inmates are selected for the facility's fine arts painting program.

The offenders housed in the minimum security area are responsible for the maintenance of the grounds surrounding the prison, and for cleaning office areas within the non-secured areas inside the main prison facility.

MCF-STW has recently undergone a number of modernization efforts, including the demolition of an antiquated medical building and construction of a modern segregation unit capable of housing up to 150 inmates.

The Prison Mirror

Notable one-time Stillwater prisoners include Frank Elli, author of The Riot; and Harley M. Sorensen, former columnist for SFGate.com. Elli wrote The Riot and other books in Stillwater prison and was a member of the Ink Weavers writing group there. Sorensen was editor of The Prison Mirror, the inmate publication still produced by the men at Stillwater. Sorensen's posthumous first book, Prison is a Place, documents life in Stillwater Prison in the early 1970s through the author's exchange of letters with a St. Paul religious studies class.

The Prison Mirror celebrated its 125th anniversary in August 2012. It was founded in 1887 with the warden's permission using funds from prisoners including the Younger Brothers, members of the James–Younger Gang, and is believed to be the oldest continuously published prison newspaper in the United States. It has been named the best prison newspaper in the United States several times, winning the Charles C. Clayton award in 1969 and 1987 from the University of Illinois – Carbondale, and a similar award from Amicus in 1985. Topically the newspaper has a tight focus on life in the prison, covering sports such as broom hockey, basketball and dodge-ball, educational pursuits and achievements of the prisoners, notable visitors and available support programs, and other matters. A regular column called "Ask the Warden" presents questions and requests to the warden. Comings and goings of staff members are often noted. Most issues feature poetry and art work produced by the prisoners. In-depth features included an interview with several 'lifers' including Harvey Carignan, an examination of Minnesota's prison commissary prices and the supplier MINNCOR, and a cover story about the aging population of America's prisons.

Appearances in media

The prison is mentioned in the 1939 James Cagney film Each Dawn I Die. It is also briefly mentioned in the 1996 Coen Brothers movie Fargo.

The 1956 book Nineteen Years Not Guilty: The Leonard Hankins' Story in His Own Words, as Told to Earl Guy describes an innocent man's experiences inside Stillwater Prison.[5]

See also

- List of jails and prisons on the National Register of Historic Places

- List of Minnesota state prisons

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Washington County, Minnesota

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ↑ Ferguson, Robert (1985-09-30). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form: Stillwater State Prison Historic District" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ↑ "Minnesota Correctional Facility – Stillwater". Minnesota Department of Corrections. 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-22.

- ↑ Mohr, Elizabeth (2008-12-19). "30 feet from freedom: the tale of a foiled prison escape". Pioneer Press. St. Paul, Minn. Retrieved 2016-04-07.

- ↑ "The Leonard Hankins Story". Retrieved 2016-11-09.